womanandhersphere

This user hasn't shared any biographical information

Homepage: https://womanandhersphere.wordpress.com

The Garretts And Their Circle: Annie Swynnerton’s ‘Illusions’

Posted in The Garretts and their Circle on July 22, 2013

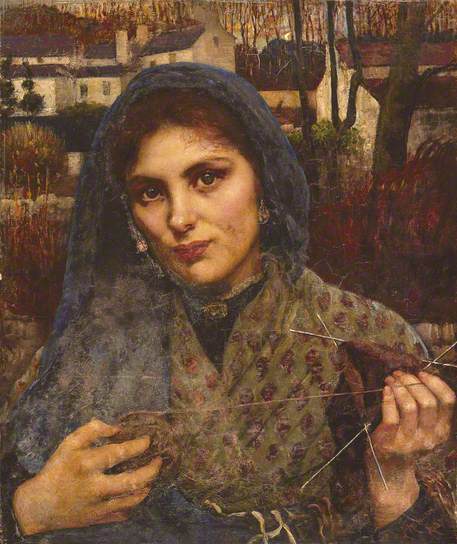

‘Illusions’ by Annie Swynnerton, Collection Manchester City Galleries, courtesy of BBC Your Paintings & ArtUK

This painting was left to the City Art Gallery, Manchester, by Louisa Garrett (nee Wilkinson, sister-in-law to Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Millicent Fawcett and Agnes Garrett.

‘Illusions’ would once have hung in Louisa’s home at Snape in Suffolk. Her house was named ‘Greenheys’ after the area of Manchester in which she and her sister, Fanny, grew up.

The way in which the Garrett circle did their best to ensure that Annie Swynnerton’s work was included in major public collections is discussed in my book – Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle- available online from me, or Francis Boutle Publishers or from all good bookshops..

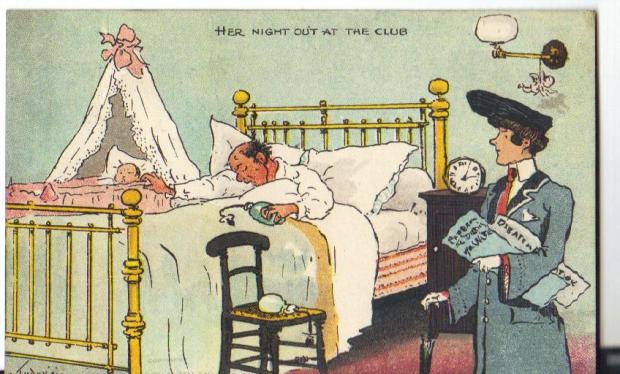

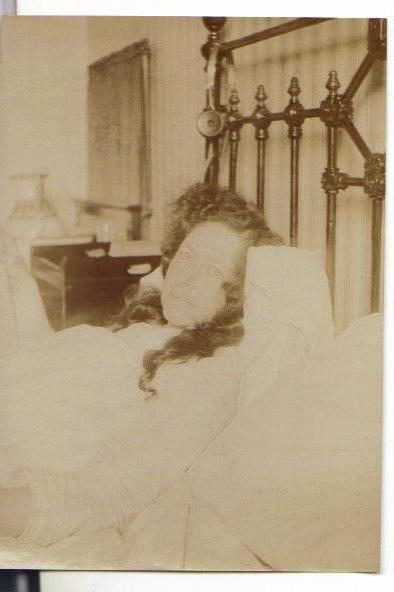

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: In Bed – Photographed With Radio Headphones At The Ready – 1920s

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on July 20, 2013

Working my way through Kate Frye’s extensive collection of photographs I have just come across this one. It is so unusual to see a photo of a woman lying in bed that I thought I must share it with you all. You’ll note the radio headphones hooked on the brass bedstead which probably dates the photo to the second half of the 1920s. The photo would have been taken by Kate’s husband, John Collins, who was a keen photographer. Kate, for her part, was a keen and early radio listener, delighting as she did in all forms of music and drama.

The Garretts and Their Circle: Annie Swynnerton’s ‘The Dreamer’

Posted in The Garretts and their Circle on July 19, 2013

The Dreamer by Annie Swynnerton, 1887. (c) Manchester City Gallery – image courtesy of BBC Paintings and ArtUK

In yesterday’s post I drew attention to Annie Swynnerton’s portrait of Millicent Fawcett. It was hardly chance that brought that artist and that sitter together; both were central figures in what I term ‘the Garrett circle’.

Today’s painting by Annie Swynnerton, The Dreamer, was originally owned by Millicent Fawcett’s sister-in-law, Louisa Garrett (nee Wilkinson) who for a while lived next-door-but-one to Millicent Fawcett and Agnes Garrett in Gower Street (the latter at no 2 and the Wilkinsons at no 6). The Dreamer was owned jointly by Louisa and her sister, Fanny, and may for a time have graced the walls of 6 Gower Street. Louisa only moved out of no 6 on her marriage to Millicent and Agnes’ youngest brother, George Garrett.

Fanny Wilkinson and Louisa Garrett did all in their power to ensure that, after their deaths, Annie Swynnerton was represented in public collections. In her will Louisa specifically left her share in this painting to Fanny and expressed ‘the desire that she will bequeath the said picture to the City Art Gallery, Manchester.’

Discover much more about the way in which the Garrett circle did their best to ensure Annie Swynnerton’s continuing reputation in my Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle- available online from me, or Francis Boutle Publishers or from all good bookshops..

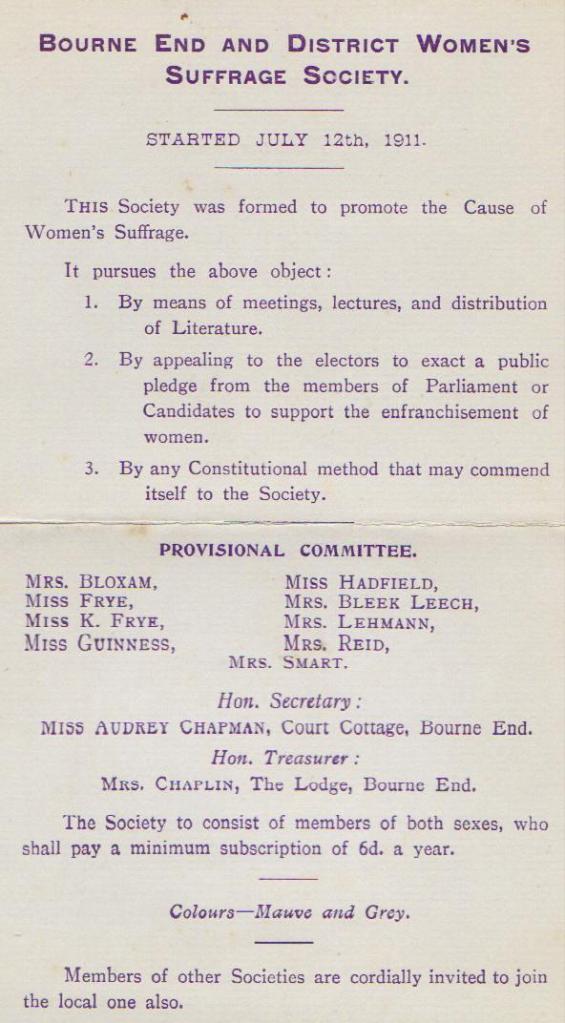

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: Live in Wood Green, 25 July 2013

Posted in Uncategorized on July 9, 2013

Do come along and experience a taste of suffrage life

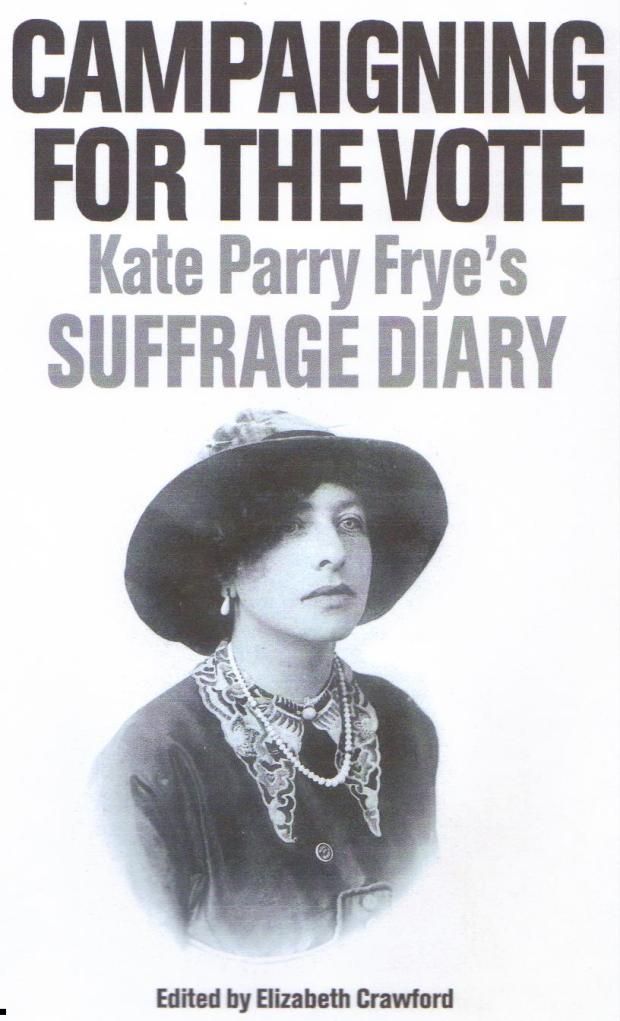

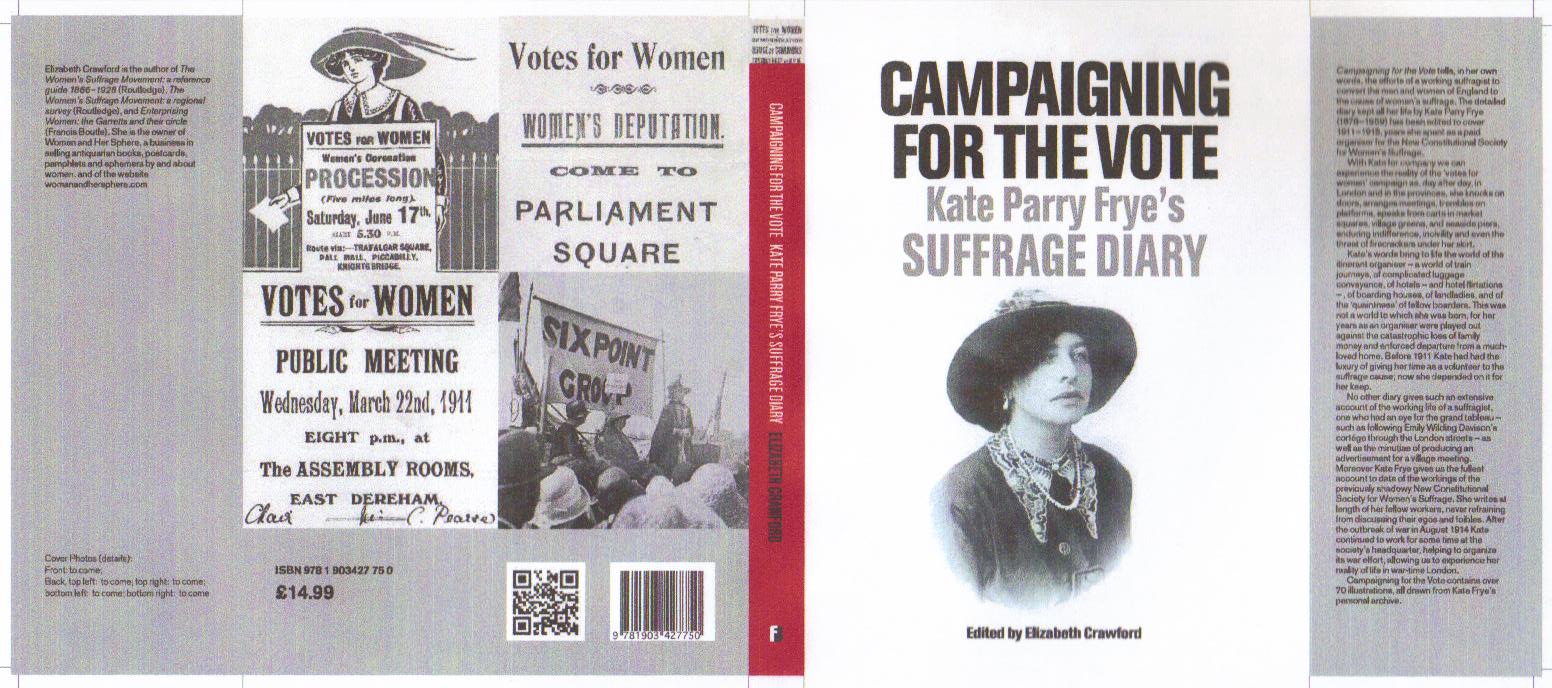

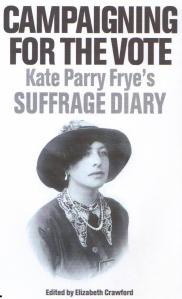

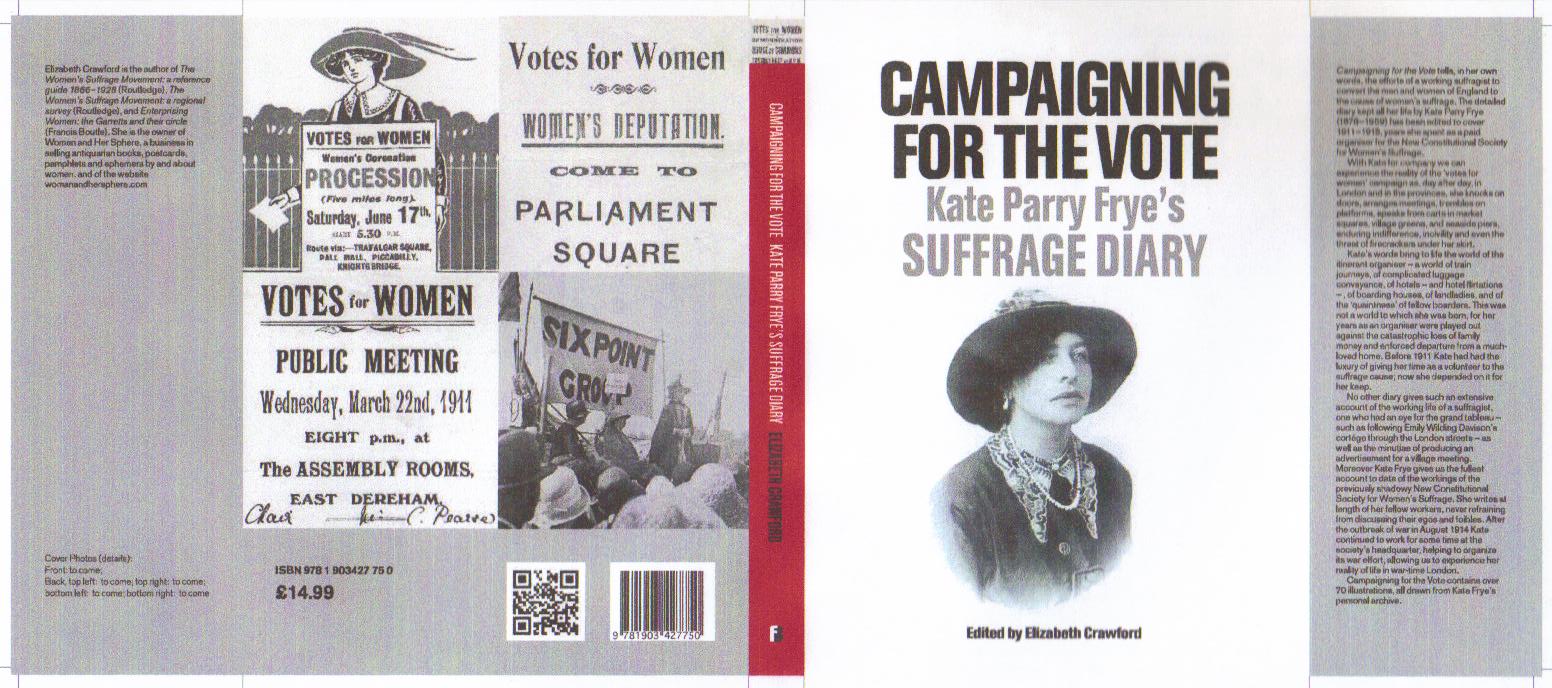

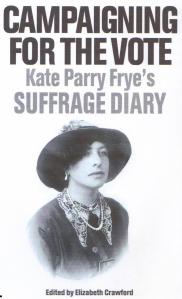

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary is published by Francis Boutle Publishers

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

For a full description of the book click here

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, London Review Bookshop (shop and online), Foyles (shop and online) – and from all good bookshops – including the Big Green Bookshop!

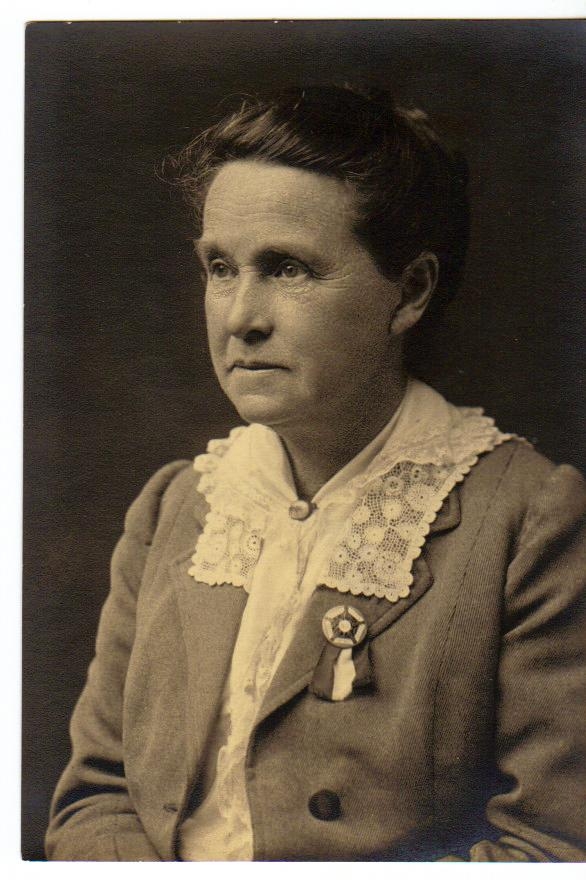

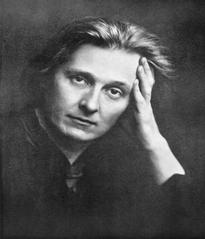

Women Writers And Italy: Dorothy Nevile Lees

Posted in Women Writers and Italy on June 17, 2013

Dorothy Nevile Lees was born in Wolverhampton in 1880, the youngest of the seven children of William and Rose Lees. The Lees were a long-established Wolverhampton family and in the 1891 census Dorothy’s father was described as a ‘justice of the peace, Mediterranean merchant and manufacturer of tinned japanned wares’. Ten years later the family were living in Old Ivy House, Lower Street, Tettenhall. For further information about Old Ivy House see here.

In 1903 Dorothy Lees travelled to Italy, arriving on 4 November in Florence, where she was to remain for the rest of her life. On 7 November her brother, Gerald, set sail for Montreal to work there as an agent for Mander Bros, the leading Wolverhampton manufacturer of paint and varnish. In the 1901 Gerald had been working as a clerk his father’s company. I sense that there may have been some kind of business failure, for in 1911 the eldest Lees son, Lawrence, was working as a’ needle manufacturer’, living with his parents, his father being described as ‘a retired export merchant’ (incidentally this is the only 1911 census form that I have seen on which the information has been typed rather than handwritten). When William Lees died in 1917 he left only £300 or so and this may be some kind of explanation as to why Dorothy left home; it was then very much cheaper to live in Italy and, if she hoped to earn money from writing, there was more picturesque ‘copy’ in Florence than in Tettenhall. In 1907 she published two books, Scenes and Shrines in Tuscany and Tuscan Feasts and Friends. She dedicated the latter book to her brother, Gerald, ‘Oceans part not kindred hearts/While they remain akin’. Below is an excerpt from the first chapter, demonstrating the potency of the Tuscan dream that has captivated English women throughout the centuries.

‘From the first moment when, in the afternoon sunshine of a day sweet and unforgettable, a bend in the road revealed it, the Villa took prisoner of my heart.

The Villa, strictly speaking, was not beautiful; its time-stained platstered walls, its lofty height, its heavily-barred windows were a little guant and forbidding; and yet, as I stepped down from the carriage, I felt instinctively that I had found the place of dreams and peace.

It was a house to enchant any lover of antiquity, with its furniture of dark oak and antique gilded leather, its ancient bronze and silver lamps, its tapestries, its painted ‘Cassoni’, in which the brides of a past day brought home their gear; its portraits of old-time Florentines in lucco or parti-coloured hose, in wigs and ruffles and brocaded coats; of ladies in Medicean costume of grave-faced priors and dashing cavaliers, some of whom lived in, and, no doubt, still haunt, the queit rooms on which they down gaze down!

Yes, it was a story-book house. So I decided that night in my quaint little bedroom, with its high wagon-roof and red-paved floor, while the moon, low in the west above the dark huddle of the woods, shone in through the window, drawing the close-crossed bars, with which Italians guard all lower casements, in clear black outline upon the opposite wall. Watching the quiet silver light, which seemed like a benediction, making the little room a holy place, and listening to the dripping of the fountain and the hooting of the owls in the profound stillness of the September night, I could but fall asleep murmuring, ‘the lot is fallen unto me in a fair ground’, since the guiding star of fortune had stood still for me above a place so sweet.’

Dorothy Lees’ Tuscan idyll did not, however, find fulfillment as the consort of an Italian conte or marchese, her lot was not be mistress of a Tuscan estate, but to be a life-long handmaid to Edward Gordon Craig, actor and director.

For it was in early 1907 that, in Florence, Dorothy met Craig, the illegitimate son of the actress, Ellen Terry, and the architect, Edward Godwin, and from then on devoted herself to him for the rest of their lives. She was the mother of one of his eight children; her son, David, was born in September 1917. Craig was by no means a constant, or appreciative, companion; Isadora Duncan was another of his lovers.

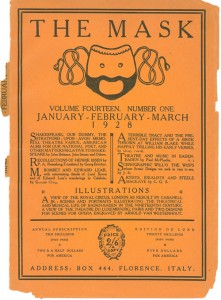

Dorothy Lees collaborated with Craig on the publication of The Mask, the journal through which he aimed to disseminate his philosophy of the theatre and to demonstrate methods of putting his ideas into practice. Dorothy was the journal’s managing editor and provided financial support from money she earned as a journalist. After Craig left Italy, Dorothy Lees lived on in Florence, rescuing his archive from the attention of the Nazis and, after the war, building up a collection of Craig-related publications for the British Institute.

Dorothy Lees’ papers are held in Harvard University – click here for a full and excellent listing of the collection. Below are descriptions of a few of the letters sent by Craig to Dorothy Lees around the time their son was born.

- (915) Craig, Edward Gordon, 1872-1966. Letter to Dorothy Nevile Lees, 1917 Sept. 5. 1 letter.

Publication business; words of encouragement for facing sad things in life; signed “ever yours.”

- (916) Craig, Edward Gordon, 1872-1966. Letter to Dorothy Nevile Lees, 1917 Sept. 13. 1 letter.

On arrangements for DNL in hospital; should not register under EGC’s name; [baby] should have plain name.

- (917) Craig, Edward Gordon, 1872-1966. Letter to Dorothy Nevile Lees, 1917 Sept. 17. 1 letter.

Concerning baptism; EGC does not want name in it (on it?) at all.

- (918) Craig, Edward Gordon, 1872-1966. Letter to Dorothy Nevile Lees, 1917 Sept. 20. 1 letter.

New prospectus for the Marionnette.

- (919) Craig, Edward Gordon, 1872-1966. Letter to Dorothy Nevile Lees, 1917 Sept. 24. 1 letter.

Glad for DNL’s sake news is good; his dissatisfaction with Mr. Furst.

- (920) Craig, Edward Gordon, 1872-1966. Letter to Dorothy Nevile Lees, 1917 Sept. 26. 1 letter.

On Mr. Furst as a worker; his “young apache;” on proper relationship between men and women; “women could make the world a much more pleasant place and life a far more pleasant time for all people if they would do what they [are] told to or asked to do.”

I think this small sample give a flavour of their relationship. Doubtless, for Dorothy life in Florence, which she describes in the opening page of Tuscan Feasts as a ‘dream city’, provided the balm to what must have been a constantly wounding – but self-chosen – way of life. Her son, David Lees, who died in 2004, was renowned as a photographer; several photographs of his father are held by the National Portrait Gallery. Alas, although surely David Lees must have photographed his mother, I cannot locate any photograph of Dorothy. Such is the fate of handmaidens through history.

Campaigning For The Vote: Kate In Dover 100 Years Ago: A Sunday Visit From John, May 1913

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 23, 2013

Kate Frye is working in Dover, lodging at 26 Randolph Gardens with the Miss Burkitts’, who are WSPU sympathisers and aunts of Hilda Burkitt, a well-known suffragette. A vignette of life in ‘digs’.

Kate Frye is working in Dover, lodging at 26 Randolph Gardens with the Miss Burkitts’, who are WSPU sympathisers and aunts of Hilda Burkitt, a well-known suffragette. A vignette of life in ‘digs’.

‘Poor Gertie’ was, as Kate explains in a previous entry, ‘Miss Odames – a being from Leicester who used to work in a Factory but is now quite well to do. She is very common and very plain.’ ‘Gertie’ was ‘Agnes Gertrude Odames, born in Leicester c 1878 who, in 1901, was a ‘corset maker’ but who, with her sister, was in 1911 able to describe herself as ‘of private means’. Gertie married in 1917 and when she died in 1951 left over £1000, having probably lived a more comfortable life than Kate. I have, as yet, been unable to identify ‘Bertie Bowler’.

Sunday 25 May 1913

A glorious day and quite hot. The others all of to Church. I as usual on Sunday took my time in getting up. While I was in the bathroom the young gentleman who we have been hoping and longing for came to say he would take the rooms. Miss Minn was in. I had to wait until he had departed to get upstairs. We are very excited.

I wore my thin coat and skirt out for the first time without a top coat. Walked along the front to the Town station and met John [her fiance, an actor] at 12.30. He had come down by the Miss Burkitts’ invitation to spend the day. We had not met for 5 months. It was very exciting. I think he was pleased and I enjoyed having him. He looks alright though a trifle thin – came to London last Sunday at the close of the Repertory season at Liverpool.

We walked along the front in the blazing sun and up and got in at 1.15. John behaved very nicely but of course he was a stranger in that homely atmosphere – however the Miss Burkitts seemed to get on with him.

We went in the garden afterwards and John took snapshots of the group and Janet [Capell] came in to be introduced. Then John and I took a tram as far as it went and strolled about the Admiralty Pier. It was a gorgeous afternoon. We had permission to be late for tea so we walked along the front and took a photograph of Mrs Wilson’s house and then back to tea.

Mrs Wilson’s house at 5 East Cliff, Dover, photographed by John Collins while he and Kate were out for their walk

Then we sat in the garden and Bertie Bowler was there and sang his Ditties. I had told John to be nice to him – and BB said afterwards how nice he was. I don’t think John knew what to make of poor Gertie. Poor soul she looked hopeless in a stiffly starched white embroidery ready made gown. She says such amazing things.

Miss Minn took herself off to Church – a thing she never does in the evening but I think she is madly jealous. She was very nice when she said good-bye to John – said ‘I like you very much – I think you are almost good enough for our darling’ – but afterwards she never referred to him. Once or twice I dragged his name in but she wouldn’t say much. Poor Miss Minn. Miss Burkitt on the other hand chatted of him and said how much she liked him.

We had to walk as the trams were packed to the roof. I was not allowed on to the station – it was like a bank holiday – so i did not wait but came straight back on a Tram – just missing Miss Minn who had gone down after Church to come back with me. When I said she was naughty to go to Church – she said she thought the others would have had the sense to leave us alone together. I was very tired.

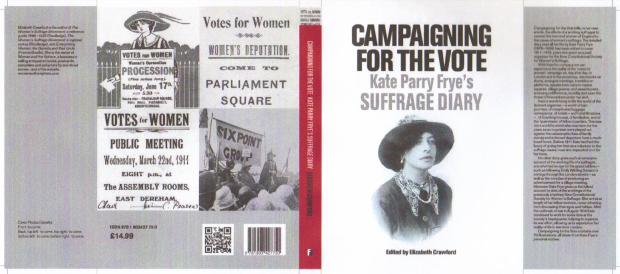

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

£14.99

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – e.crawford@sphere20.freeserve.co.uk, from all good bookshops – especially Foyle’s, London Review Bookshop, Persephone Bookshop, British Library Bookshop, Daunts Bookshop, The National Archives Bookshop and Newham Bookshop. Also online – especially recommend very favourable price offered by Foyle’s Online (and they pay all taxes!)

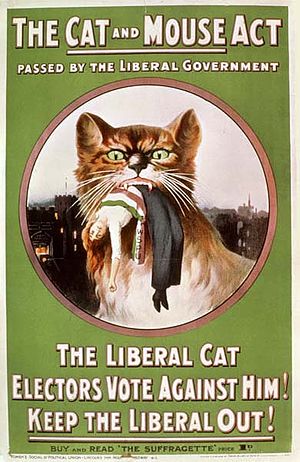

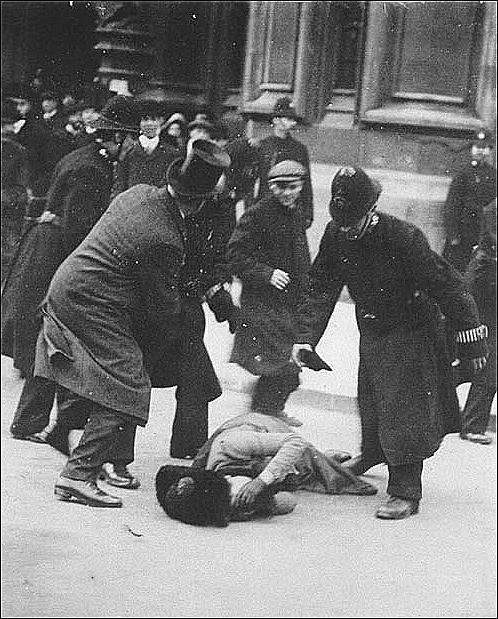

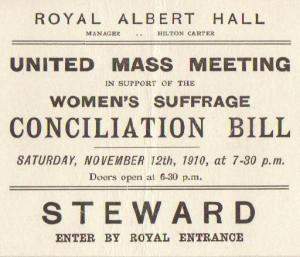

Campaigning For The Vote: Kate Frye and ‘Black Friday’, November 1910

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 20, 2013

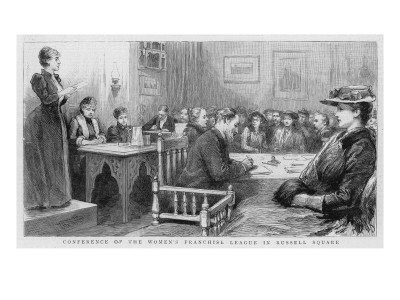

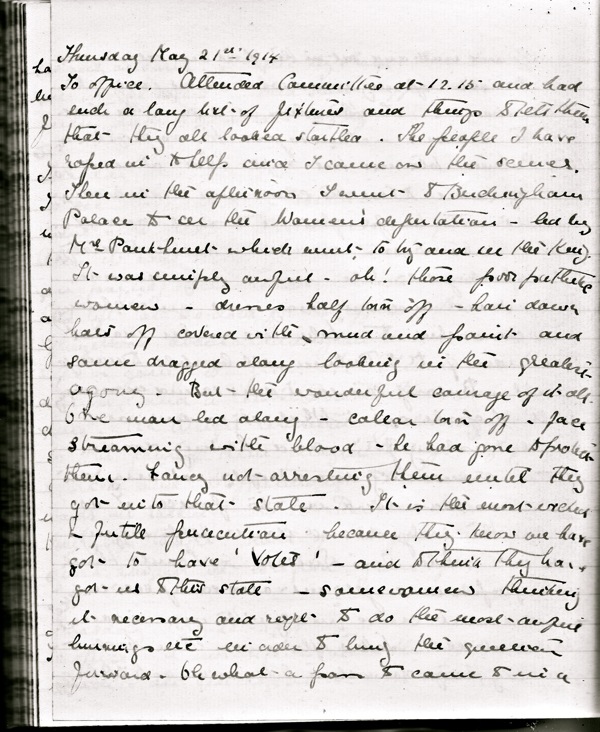

Kate Frye was present on so many important suffrage occasions – including ‘Black Friday’ – 18 November 1910. On this day the suffrage societies learned that the Conciliation Bill, on which they had pinned their hopes, would be abandoned as, with the two houses of Parliament locked in confrontation over Lloyd George’s budget, Parliament was to be dissolved. The police were out in force and employed brutal tactics to break up the women’s demonstration.

Kate Frye was present on so many important suffrage occasions – including ‘Black Friday’ – 18 November 1910. On this day the suffrage societies learned that the Conciliation Bill, on which they had pinned their hopes, would be abandoned as, with the two houses of Parliament locked in confrontation over Lloyd George’s budget, Parliament was to be dissolved. The police were out in force and employed brutal tactics to break up the women’s demonstration.

Only a short excerpt of Kate’s ‘Black Friday’ diary entry appears in Campaigning for the Vote because it occurred in the period before Kate began work as a paid organizer for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. There was, alas, just too much material in her diary to make a book out of her whole suffrage experience. So, for those who would like more, here are full details of Kate’s experience that momentous day.

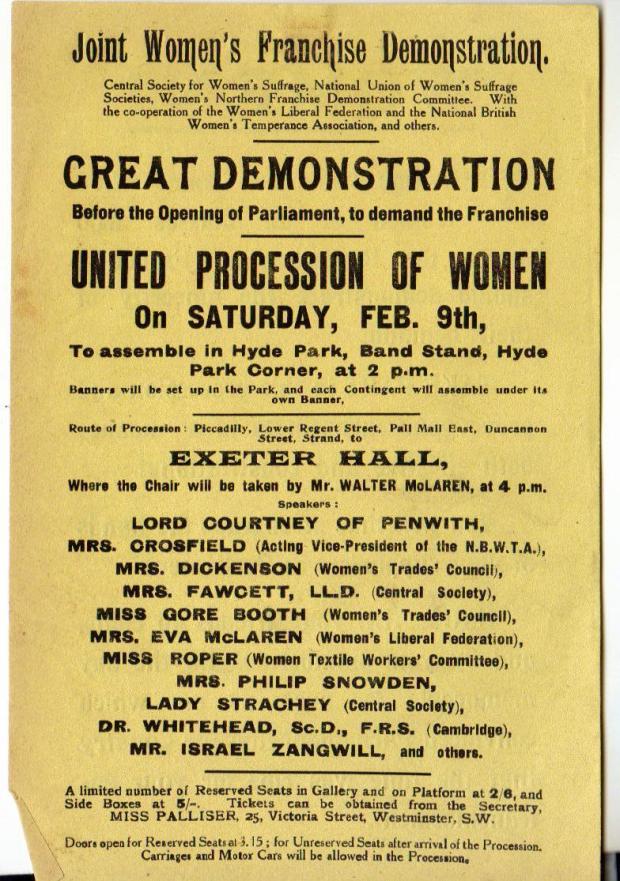

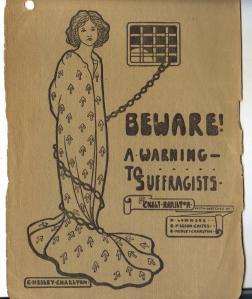

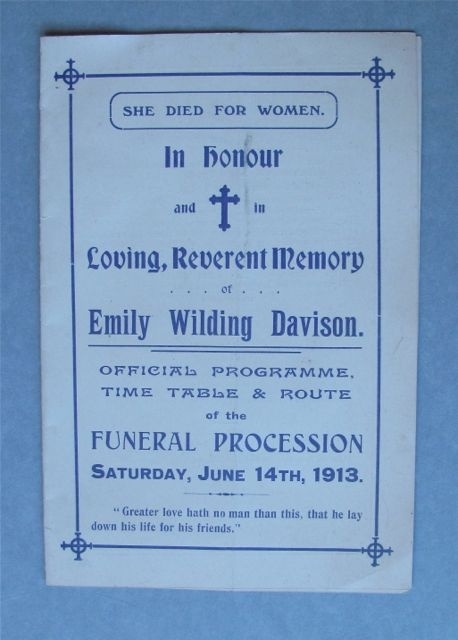

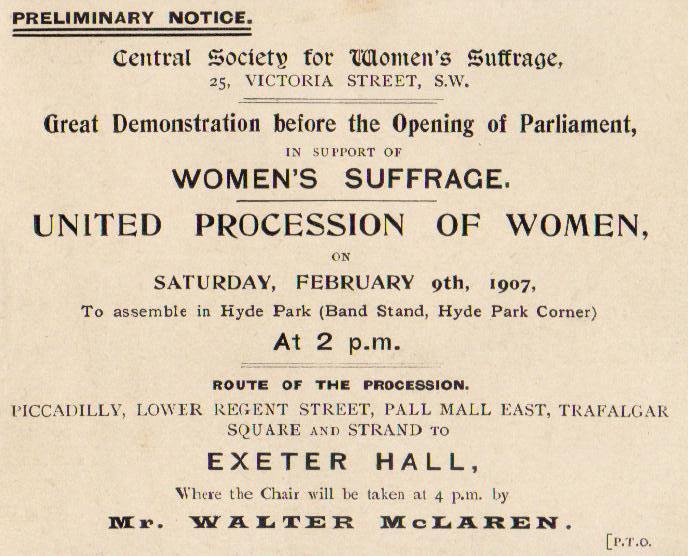

Kate’s invitation from the WSPU to attend the protest, Friday 18 November 1910. Just imagine how many of these fragile flyers lay torn and trampled on the ground at the end of ‘Black Friday’. Kate carefully preserved hers, took it home and laid it in her diary

Friday November 18th 1910

Up in good time. Brushed Mickie [her dog] then took him for a walk – then started at 10.30 for the Caxton Hall. Train from Notting Hill Gate to St James’ Park. I got there about 12 – and the hall was already full and the crowd hanging about were soon after turned out of the vestibule – so I stood some time on the steps. Then from there we were turned into the street and I waited there, chatting with different women, till about 12.40 when the 1st deputation left the Caxton Hall for Parliament Square.

They were soon swallowed up in a seething mob and I simply flew with many other women by short cuts to Parliament Square where I landed more or less by chance in the thick of it. One could hardly see the plan of it all amid the hurly burly excitement, shouts, laughter applause & rushes of the enormous crowd which grew every minute. I was almost struck dumb and I felt sick for hours. It was a most horrible experience. I have rarely been in anything more unpleasant – it was ghastly and the loud laughter & hideous remarks of the men – so called gentlemen – even of the correctly attired top-hatted kind – was truly awful. It made all the men and women seem mad together. And the poor women – the look of dogged suffering & strain on their faces.

I first reached the wall of the moat [round the Houses of Parliament] at the angle so I could see the door plainly and Mrs Pankhurst and the elderly lady [Elizabeth Garrett Anderson] – over 70 years of age – with her. Then I saw policemen breaking up the little standards held by a group of women. I saw deputations pass along and ugly rushes and ever the crowd grew.

I stood some time but I had to give up my place by the wall people pushed so and I was awfully afraid of getting crushed. So I got out to the road and there watched the deputations come along and saw the horrible hustling by the crowds of roughs and overheard the hideous laughter and remarks of the men looking on. Half of them made the remark that it was the funniest thing they had ever seen in their lives – all had their mouths open in an insane grin. One or two were so horrible that I just gazed upon them till they noticed me and moved away, not liking I suppose to be overheard. Several spoke to me – many indignant: ‘What good do you suppose this will do?’ ‘What else would you suggest?’ said I. Then he began the usual – that the militant methods had disgusted all nicely feeling people etc. I turned his attention to my two badges – constitutional societies, as I told him – and asked ‘What help have you ever given us?’ He walked away. Not one man did I hear speak on the women’s side. There may have been some, but not near me.

I saw Captain Gonne led off & heard afterwards of his doings. Many women there were of the WSPU – and a few London Society [ie members of the constitutional NUWSS society] – all standing about perfectly wretched & green – cheering them on to battle and off to Cannon Row when arrested. One poor lady in her wheel chair [probably Rosa Billinghurst]– propelled by hand – followed in the wake of a deputation – generally 6 to a dozen people – she rang her bell violently and the crowd gave way before her – it was a funny but dreadfully tragic sight.

As the crowd grew and the crowd kept being pressed back – I moved away and once, seeing some fighting women & policemen on the pavement coming my way, I stood back to the railing expecting them to go by. But, oh no – a burly policemen, taking me for one of a deputation, caught hold of me with an ‘Out you come’ and for some minutes I was tossed about like a cork on an angry sea, turning round and round – sometimes bumped on to a policeman – sometimes on a hospital nurse, who was fighting for all she was worth – pale to the lips but determined (and I afterwards saw her led off arrested ) – until I was with the others pushed out of the danger zone.

The others went back but I sat down by the railing for a few minutes. I can’t say the man actually hurt me and I was too excited to realise quite what was happening and I was so thickly dressed as not to feel the bumps much – but it wasn’t nice. I don’t know I could have spoken if I had wished to – but I didn’t wish and I didn’t speak. What I felt was – I am not going to get out of the trouble by saying I am not one of them for I am in heart and anyway he will probably think I am trying to trick him and it will do no good and if these women can stand so much I can stand this little. And of course it was nothing really – only a new experience.

Two ladies – one quite elderly came out of their first battle determined not to go back into it. They were a pitiable spectacle – their nerve had gone. One felt so sorry – they were beside themselves and were not aware they had in fact turned ‘coward’. A little lady – evidently there to plead with the faint hearted – spoke quietly to them, urging them to go when they felt rested. ‘But we couldn’t’, they said, ‘we have been half killed’. ‘Oh, but you must – you must go back again and again and again’ and so on. And I spoke to them – thinking an outsider’s word might turn their attention. Their eyes were brimming. They told me that they were supposed to go on till their strength was exhausted – they thought theirs was – but it wasn’t. But poor souls – their fight – of course they had never realised the awfulness of the business and what they would have to endure until they should fall fainting or injured. I wonder if they went back. Perhaps courage did come back to them but who could blame them – they were very saddening.

On the next page of the diary entry Kate laid in the WSPU’s pamphlet prepared as a result of ‘Black Friday’

I couldn’t seem to leave even when I had crossed to the station side. I stood and watched the arrested being led off – & gave them a send off – but soon after 2 I gave it up and, leaving the horrid spectacle, went in to Westminster Bridge station. They were beginning to clear the Square of people. Hundreds of policemen were arriving and one could less than ever see the plan of it all. A lot of Yankee sailors had been mystified but delighted and a lot of people were frankly puzzled by it all – and it was a sad business explaining to them. I got back cold to the bone – fetched my lunch on a tray – and was glad of hot soup.

After a visit to friend for tea on way home] grabbed up some evening papers then home. Couldn’t keep my mind off the morning’s experience and we talked of little else. 105 have been arrested. It was about the most bitterly cold night I have ever been out in.’

As a result of what she had witnessed on ‘Black Friday’ Kate Frye joined the WSPU

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford. Now, alas, out of print

- ‘Campaigning for the Vote’ – Front and back cover of wrappers

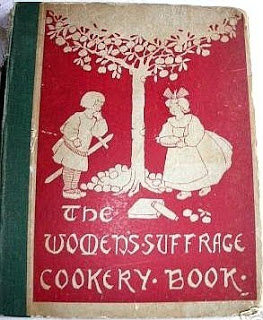

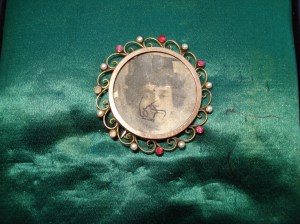

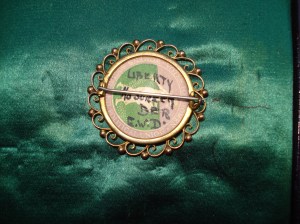

Collecting Suffrage: Suffragette Jewellery And ‘The Antiques Trade Gazette’

Posted in Collecting Suffrage on May 17, 2013

This week’s issue of the Antiques Trade Gazette contains a letter from me protesting against the mis-describing of random pieces of Victorian/Edwardian jewellery that have a combination of metals and/or stones approximating to the purple, white and green of the WSPU, as ‘suffragette’.

Here is the text of the letter:

‘As a long-established dealer in suffragette memorabilia I must try once again to take a stand against the mis-labelling as ‘suffragette’ of any pieces of jewellery that contain stones approximating to some shade of purple (or pink or red), white and green.

I see on page 32 of this week’s ATG that two auction houses so described 3 brooches/pendants. I have no idea if the intrinsic value of the items was commensurate with the sale price achieved, but of one thing I am certain – there was nothing in the lot descriptions that convinced me that these pieces had any association with the suffragette movement. I only hope that those bidding were not doing so with any thought that they were acquiring a piece of suffragette history. It should be obvious to anyone with any historical sense that it is necessary to have a much more detailed provenance – a documented history – other than some woolly description about ‘purple, white and green’.

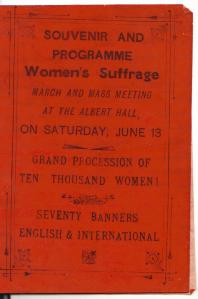

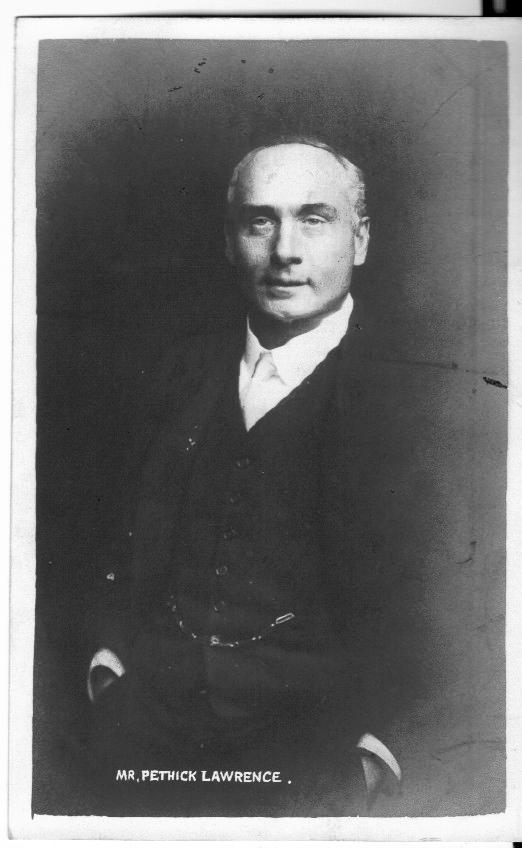

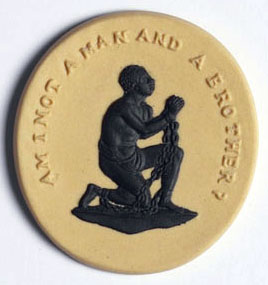

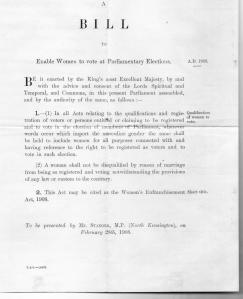

The ‘colours’ were the invention of one of the leaders of the WSPU, Mrs Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, as a way of creating a ‘brand’ for the WSPU and were first used in June 1908 at a grand rally held by the WSPU in Hyde Park.‘The Public Meeting Act’ of December 1908, mentioned in the ATG piece, was intended, although notably unsuccessful, to prevent suffragettes from heckling ministers – not to prevent suffragettes themselves from holding meetings. It was not until years later – in April 1913 – that there was any prohibition on the WSPU holding meetings in public parks. Moreover, Britain was never such a repressive country that suffragettes found it necessary to wear jewellery ‘in the colours’ as a secret token of allegiance. Quite the reverse; women wore their badges (also now very collectable) proudly –advertising the WSPU and many other suffrage societies.

Since each of these societies followed the WSPU lead and adopted an individual combination of colours of their own I am surprised that auction houses and dealers have not yet leaped onto that bandwagon. For instance, the colours of the main suffrage society – the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies – were red, white and green. Just think how many pieces of jewellery with stones in those colours could be described as ‘suffragette’ if we were seriously to follow the ‘purple, white and green’ rule.

I have studied the suffragette movement in depth – in all its manifestations – and can report that there is no evidence that ‘suffragette’ jewellery was made in anything like the quantity flooding the auction houses and, of course, Ebay. Moreover the only commercial company known to have made and retailed ‘suffragette jewellery’ as such was Mappin and Webb (Stanley Mappin was a convinced supporter of the WSPU – joining in the suffrage boycott of the 1911 census). I would be interested to learn of any documentation citing any other commercial company as maker of ‘suffragette jewellery’.

Other jewellery was made by individual artist craftswomen- such as the well-known enameller Ernestine Mills – to sell at fund-raising suffragette bazaars and may well have included references to suffragette colours and motifs. On occasion one can find pieces that demonstrate clearly their suffragette provenance. One such is a pendant made – in purple, white and green enamel – from a design by Sylvia Pankhurst. The pendant is long since sold but I use the image of it as the identifier on my website – womanandhersphere.com – on which those who really want to know about ‘suffragette’ jewellery can find more information – as they can in the entry under ‘Jewellery and Badges’ in my The Women’s Suffrage Movement; a reference guide, published by Routledge. Ignorance should not be a reason for allowing auction houses and dealers to perpetuate the ‘suffragette jewellery’ myth. As I say, I specialize in suffragette memorabilia but could not possibly bring myself to sell something as ‘suffragette’ if I was not certain that it had an authentic provenance.’

I don’t suppose this will make a jot of difference – but I try. A suffrage collector told me recently that, after buying an item on Ebay and then doing a little research, he realised that the item was not of original suffragette provenance. When he protested to the Ebay seller, he was told, ‘Prove it’. That was not a valuable item, so it was not worth the trouble of engaging in a prolonged battle with a seller who lacked both historical knowledge and a conscience. However, I am sure there are cases, particularly of jewellery, where sales are made that would not have been without the spurious ‘suffragette’ description.

Caveat Emptor

Buy only from a reputable dealer.

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Frye in ‘History Workshop Online’

Posted in Uncategorized on May 13, 2013

Do click History Workshop Online

to discover how, in a dark and dank north-London cellar, I first encountered Kate Parry Frye and how I slowly recognized the importance of her diaries are to those interested in the suffrage movement.

To buy Campaigning for the Vote, published by Francis Boutle Publishers, £14.99 click here

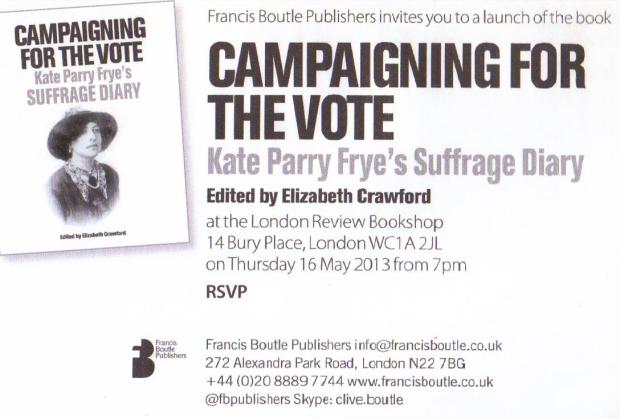

Campaigning For The Vote: Book Launch Invitation

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 9, 2013

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Frye And The Problem Of The Diarist’s Multiple Roles

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 7, 2013

In the following article I discuss the ethics of ‘mining’ the diary that Kate Parry Frye kept for her entire lifetime in order to re-present her in one role only– as a suffragist. The piece is based on a paper I gave at the 2011 Women’s History Network Conference. Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary is published by Francis Boutle Publishers at £14.99

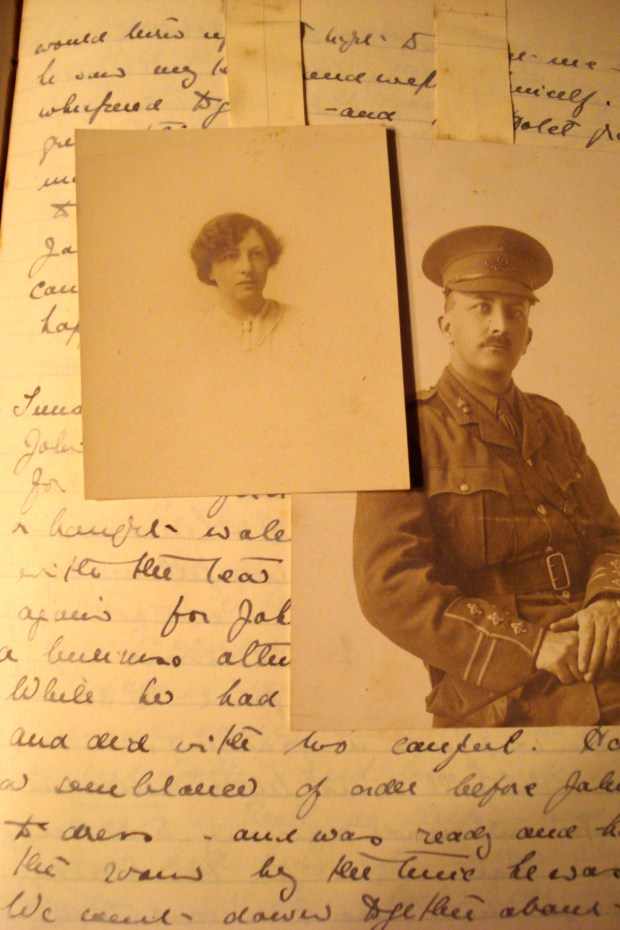

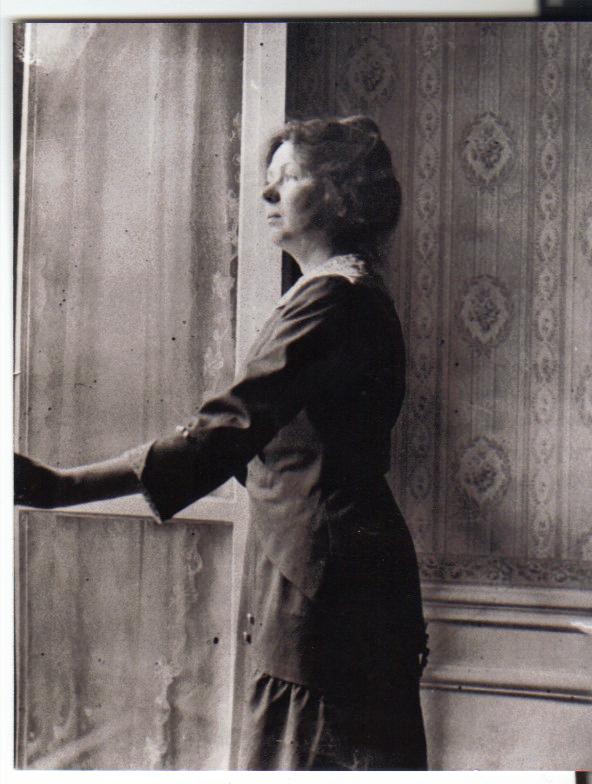

Kate Parry Frye[1] was a diarist. She was also a girl, a young woman, a middle-aged woman, an old woman, a daughter, a sister, a cousin, a niece, a fiancée, a wife, an actress, a suffragist, a playwright, an annuitant, a letter writer, a Liberal, a valetudinarian, a playgoer, and a shopper. She was a rail traveller, a bus traveller, a tube traveller, a reader, a flaneur, a friend, and a political canvasser. She was a diner – in her parents’ homes, in digs, in hotels, in restaurants, in cafés and later, of necessity, a diner of her self-cooked meals. She was an enthusiast for clothes, a keeper of accounts, a reader of palms, a dancer, a holidaymaker, a visitor to the dentist, to the doctor, an observer of the weather, a worker of toy theatres, a needleworker, an animal lover – indeed dog worshipper – a close observer of the First World War and then of the Second.

She was radio listener, a television viewer, a neighbour and, finally, a carer, recording in detail the effect on her husband of the remorseless onset of dementia and the disintegration of his body and mind. Every one of these roles is played out in minute detail in the diaries Kate Frye kept for 71 years, from 1887, when she was 8 years old, until October 1958, barely three months before her death in February 1959.[2]

Moreover, each role has its variations, depending on time and place. Thus, for example, as a middle-class daughter, Kate Frye played the pampered child, the indulged adolescent and, later, the resentful adult.

She was for many years supported financially and lived comfortably. In early womanhood she was afforded considerable freedom, her parents allowing her, indeed encouraging her, to train as an actress and to travel around Britain and Ireland with a repertory company. When that venture proved unprofitable she was able to return to life as a daughter-at-home, a role that appears to have combined the minimum of domestic chores with the maximum of freedom. Until December 1910 the family divided their time between two homes – a house, later a flat, in North Kensington and ‘The Plat’, a large detached, much-loved house on the river at Bourne End in Buckinghamshire.

But Kate Frye was also the daughter of a man whose business failed, whose lack of financial acumen she judged harshly, forcing as it did her mother, her sister and herself to leave their homes and sell all their possessions. Before 1910 there had been periodic indications of financial instability, when, for instance, ‘The Plat’ was let out for the summer, but Kate’s father failed to take his wife and daughters into his confidence, making the ultimate catastrophe all the more shocking. To Kate’s shame the family subsequently relied on the charity of her mother’s wealthy wine-merchant relations, the Gilbeys.[3] Her role in this performance might be studied, shedding as its does a clear light on the precarious reality of the long Edwardian summer. One year Kate could take for granted a life of boating and regattas, dressmakers, cooks and maids, the next she was living in dingy digs, attempting to raise money by hawking the family jewellery and old clothes around shops, while wondering if her relations had remembered to send the remittance and what she would do if they forgot..

Or perhaps one could look through Kate Frye’s eyes at the reality of working the towns of Edwardian England, Scotland and Ireland as an actress.

For instance, between September and December 1903 she was a member of a Gatti and Frohman touring production of J.M. Barrie’s Quality Street and writes in considerable detail of company train travel, theatrical lodgings and the other members of the cast, among who was a young May Whitty. Kate was paid £2 a week and includes in the diary some weekly accounts, which could be studied in conjunction with the management’s financial accounts of the tour.[4] Or her diary could be used to give an insight into the issue of class and gender in the Edwardian theatre; Kate’s experience does not indicate that family and friends felt that her new role was in any way either imprudent or declassé.[5] Or her diary might be used to research the behind-the scenes world of post-1918 theatre, as Kate reports on her husband’s attempt to earn a precarious living as actor and stage manager.[6] Kate’s involvement with theatre saw her performing on both sides of the stage – in her role as an actress and, in the auditorium, as a spectator – and her diary might also be used to study of the habits of playgoers over the decades, recording as it does her comments on the vast number of performances she attended. On occasion she thought nothing of seeing two plays in one day.

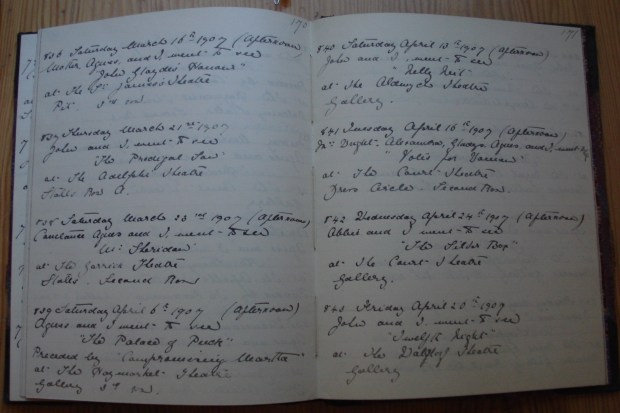

Kate kept a separate record of all the plays she saw – including Elizabeth Robins’ ‘Votes for Women!’

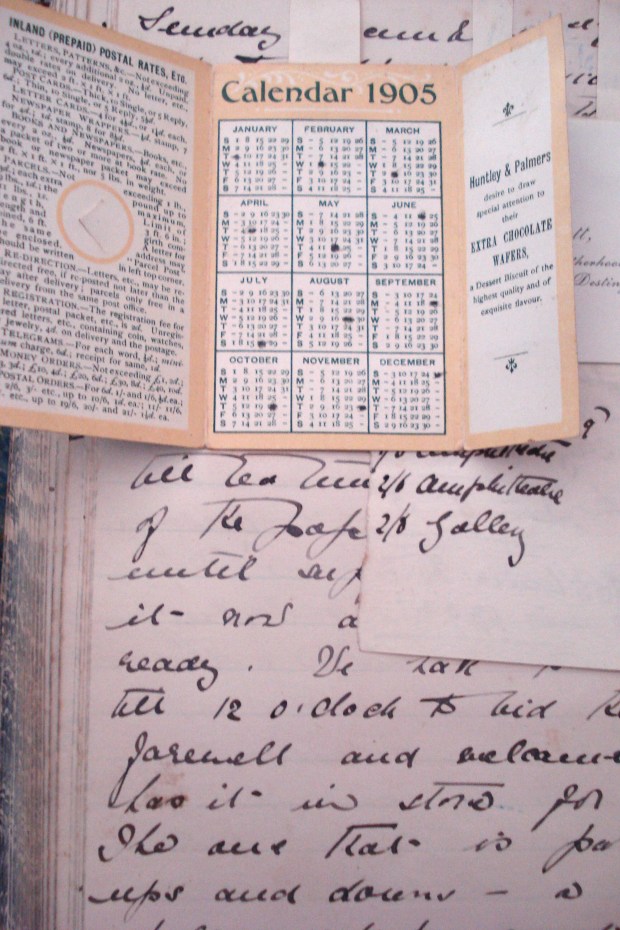

Or perhaps one could use her diary to study the nature of ill-health, real or perceived. Menstrual pain – ‘the rat pain’ – lurks behind some of Kate’s continuous complaints of ‘seediness’ and included in some of the diaries are small yearly calendars with the date of each menstrual period marked in pencil.

But the feeling of ill-health suffered by Kate, by her elder sister, Agnes,[7] and their mother was due to more than menstruation. For weeks at a time, year after year, one or the other, or all three, are confined to their beds. The doctor calls – and is paid – medications are prescribed and taken. For some of the time ‘seediness’ is endured and Kate, at least, gets on with things. It is noticeable that when she has an active life to lead, whether on tour as an actress or as a suffrage organiser, she makes many fewer complaints of ill-health. It is difficult to avoid the thought that some, at least, of the malaise was due to depression occasioned by lack of occupation. Kate did, after all, continue fit and healthy until she was 80. The diary could be read and edited to bring this aspect of her life to the fore, studying the links, in the first 50 years of the 20th century, between status, expectation and occupation – or lack of it – and mental and physical wellbeing Certainly Kate’s sister, who never worked and appears to have had few interests, seems to have given up on life, spending much of her later years in bed and drifting into death. However, although these aspects of Kate Frye’s life are intriguing, it is for her involvement with the Edwardian suffrage movement that she is now likely to be remembered. For Kate Frye’s diaries have been directed, by chance, towards an editor whose research interests centre on suffrage.

Kate was what one student of diary writing terms a ‘chronicler’, that is her diary was a ‘carrier of the private, the everyday, the intriguing, the sordid, the sublime, the boring – in short a chronicle of everything’ and in its extent is not a little daunting.[8] But, reading the volumes covering the years prior to the First World War, one quickly realises that involvement in one of the major campaigns of the day provided Kate’s life – and her diary – with a focus. For the Frye family’s descent into near, if genteel, destitution coincided with the growth of the suffrage movement, which subsequently provided Kate with employment. Although she was untrained for any career other than acting, which she had found, in fact, did not pay, work of a political nature was not outside her sphere of knowledge, for one of her earlier roles had been that of the daughter of an MP. Kate’s father, Frederick Frye, had been the Liberal member for North Kensington from 1892 to 1895 and an interest in politics was taken for granted within the family. Over the years Kate had helped her mother with the regular ‘At Homes’ held for the Liberal ladies of North Kensington and had accompanied her father to many a political meeting.

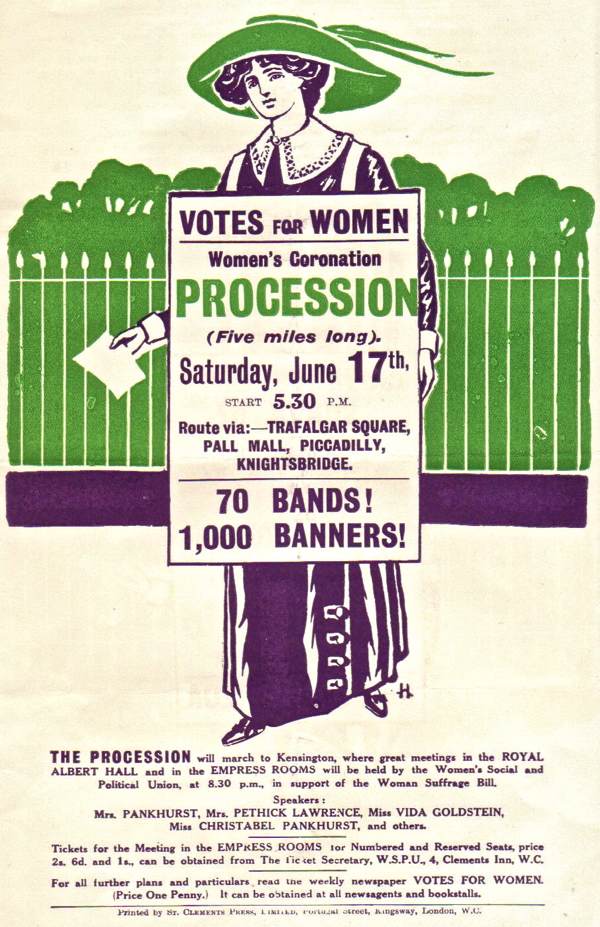

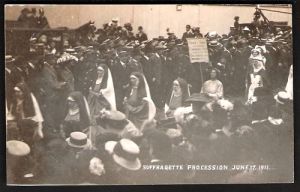

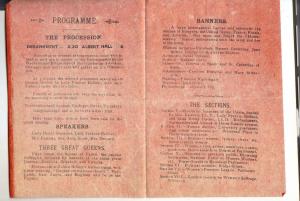

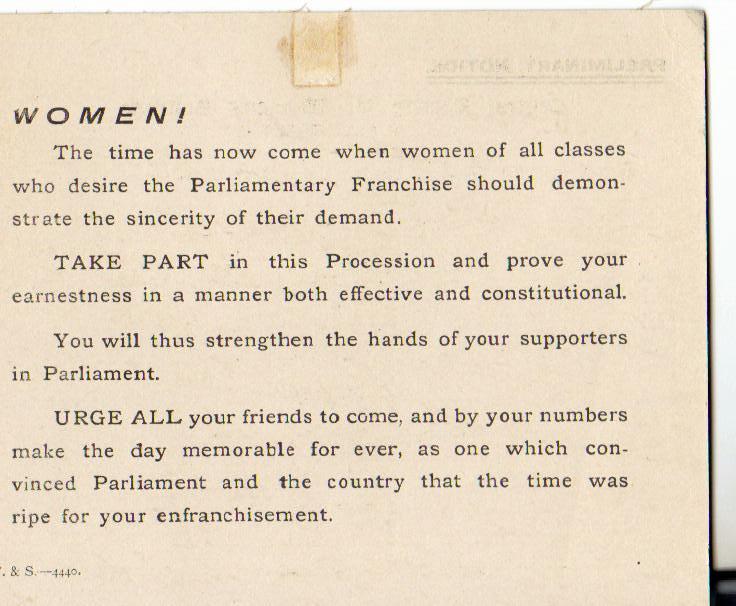

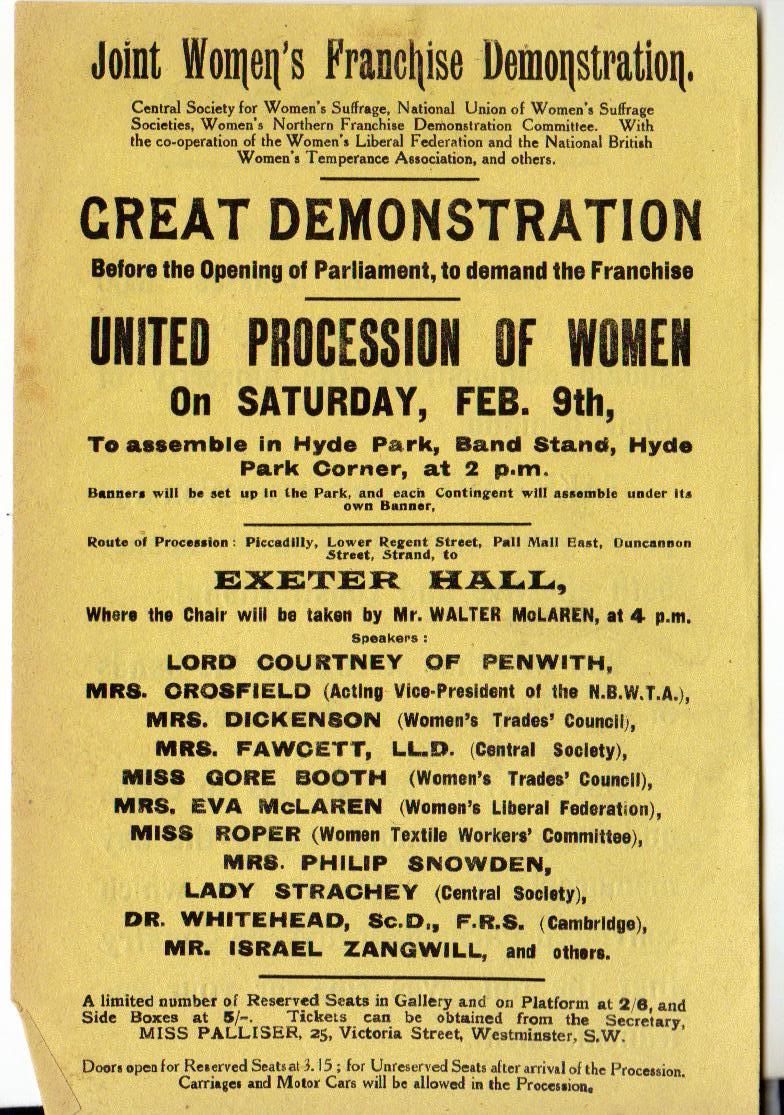

The diary entries trace her growing involvement in the suffrage campaign, from participation in the first NUWSS ‘Mud March’ in early 1907, through her performance as a palm reader at numerous fund-raising suffrage bazaars and dances, attendance at meetings of the Actresses’ Franchise League, marching in all the main spectacular processions, stewarding at meetings, bearing witness to the ‘Black Friday’ police brutality in Parliament Square on 18 November 1910, to her employment, from early 1911 until mid-1915, as a paid organiser for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. The diary, as edited as Campaigning for the Vote, highlighting the detail Kate provides of daily life as a suffragist and illustrated with the wealth of suffrage ephemera with which she embellished the original, is an interesting addition to published source material.

But what are the ethics of spotlighting this one role – or any role – from a lifetime performance? Kate’s diary seems to lend itself quite naturally to a style of editing that sets her entries, replete with delightfully quotidian suffrage detail, within a linking narrative, explaining the greater campaign and providing information on people she meets in the course of her days. But, increasingly uneasy, the editor of Kate Frye’s diary felt it necessary to take soundings from commentators on diary writing in order to discover whether the perceived problem, that of highlighting only one of the diarist’s multiple roles – one of her many selves, is one that others have resolved.

Robert Fothergill’s Private Chronicles, published 35 years ago, is generally considered the earliest academic work to have made a serious study of diary-writing.[9] In his study Fothergill considered the diaries both of men and of women but since then much of the attention the genre has received has concentrated on diary writing by women. For in the 1980s and 1990s, with the growing interest in women’s history, academics such as Margo Culley, Cheryl Cline, Harriet Blodgett, Suzanne Bunkers and Cynthia Huff saw women’s diaries as an exciting new source through which to re-examine and re-envisage women’s lives.[10] As Bunkers and Huff wrote, ‘Within the academy the diary has historically been considered primarily as a document to be mined for information about the writer’s life and times – now the diary is recognized as a far richer lode. Its status as a research tool for historians, a therapeutic instrument for psychologists, a repository of information about social structures and relationships for sociologists, and a form of literature and composition for rhetoricians and literary scholars makes the diary a logical choice for interdisciplinary study.’[11] These writers use metaphors such as ‘weaving’, ‘quilting’, ‘braiding’ and ‘invisible mending’ to describe the way in which a woman fashions her diary, a diary of dailiness rather than of great moments. But that ‘weaving’ or ‘quilting’ or ‘braiding’ lies at the heart of the problem. Is it legitimate to unravel this self-construction and fashion it into something else?

That question might be answered quite simply by a judgment made in 1923 by Sir Arthur Ponsonby and much quoted, even by the American women historians of the 1980s. For in English Diaries, Ponsonby was adamant: ‘No editor can be trusted not to spoil a diary.’[12] For his part, Robert Fothergill stated that the only respectable motive behind the amputation of a diary was the desire to make it readable – ‘commonly the abridgement or distillation of an unwieldy original, through the elimination of whatever was considered stodgy, pedestrian or repetitious’.[13] But such an ‘amputation’ is not unproblematic, for what might be considered stodgy and pedestrian to one reader, or in one decade, might be lively and interesting to the next. To anyone interested in the daily life of a suffragist, even the repetitions in Kate Frye’s daily life are revealing. Cheryl Cline elaborated Fothergill’s point, writing, ‘The most sensitive and careful editors, in cutting what they may feel unimportant, irrelevant, repetitious or even “too personal”, walk a very fine line. They may end up, for all their good intentions, ruining the work. Many editors have been neither sensitive nor careful. Editors have cut manuscripts they felt were too long, padded those they thought too short; re-arranged material to suit themselves; bowdlerized writings which revealed the less-than-perfect character of their authors. Too often, they have destroyed the originals once the edited version was published’.[14] So reservations about editing Kate Frye’s lifetime performance to refashion it as a ‘suffrage diary’ are, perhaps, not unjustified, although Kate Frye’s published diary will be neither ‘padded out’, or ‘bowdlerized’, nor will the original be ‘destroyed’. However, the charge of ‘re-arrang[ing] material’ is, perhaps, not inappropriate. It is not that the published entries will have been re-arranged, rather they will have been accorded a prominence they did not have in the original.

It is worth remarking that much of the academic literature on diary writing concentrates on the published diary.[15] There appears to be little recent consideration of the ethics of, as Bunkers and Huff put it, ‘mining’ a manuscript diary for the light it throws on particular aspects of the past, other than the difficulty this creates for those critiquing diary writing per se. Indeed, these authors appear to suggest that it was only in the past that a diary would be treated in this way. Fothergill touched on this point, condemning most severely ‘the ravages of editors, committed in, amongst other things, the name of thematic unity, writing that, from the point of view of his study of diaries, ‘A fatally damaging editorial approach is the subordination of a diary’s general interest to a specialist one, retaining only what is of use to the political or religious historian, for example.’[16] However Cheryl Cline has taken a more tolerant attitude to this aspect of diary editing, commenting ‘The urge to make a “good story” out of a diary that seems rambling and disjointed…is the motive which guides many an editor’s blue-pencil. While many diaries..are written around a theme .. or an event .., most private writings are disjointed and far-ranging. In this case material may be extracted from them and shaped into a more cohesive narrative.’[17] She then cites, as a well-known example of editing for story, A Writer’s Diary, compiled from Virginia Woolf’s diary by Leonard Woolf.[18] Kate Frye’s diary, edited to tell her suffrage story, might, therefore, be said to be keeping exalted company.[19] However it is certainly true that since the middle of the 20th century, the move in diary editing has been towards the unabridged text, complete with full scholarly apparatus. But Kate Frye would never be given that kind of treatment. So is it better to give a wider audience a ‘ravaged’ text – or to leave it, unpublished, in its wholeness on the archive shelf? An argument for leaving it untouched might well be made by the academics who have stressed the importance of the diary as a complete self-construct, a form of autobiography or life writing.[20] The author has considerable sympathy with this viewpoint, while recognising the specific interest to students of women’s suffrage in retelling the story of Kate’s suffrage years.

But perhaps, if theory cannot provide a clear answer, we should look for guidance to the diarist herself. What would Kate Frye have liked done with her text? Although she has been dead for 50 years that text is still alive with her personality and it is not inconceivable that someone who put so much of herself onto the page, developing her writing skill as she shaped her life, would have been happy to have known that she would one day reach out to a wider audience.

In this context it is worth considering for whom Kate Parry Frye had been performing. Most certainly in her diary she acted out her days for herself. From her very early years the diaries had become an essential part of her life. On occasion she discusses whether to bring her diary writing to an end, but always decides to carry on. Until mid-1916, utilising the format that Cynthia Huff describes as ‘self-determined,’ Kate wrote her entries in a large ledger-type book, embellishing them with the addition of relevant ephemera.[21] When, on 16 November 1913, on reaching the end of yet another of these books, she wrote ‘And so I have come to the end of this volume with no book to go on with though I have written to Whiteleys.[22] It would be more sensible to leave off writing a diary – at any rate such an extensive one – but more lonely’. But she did acquire another volume from Whiteleys, although that was to be the last of this kind and she afterwards continued her record in purpose-made diaries, adhering, more or less, to the space allocated for each day and no longer inserting additional material..

So that is one explanation as to why Kate kept her diary; it was her daily companion. In it she depicts herself as slightly aloof from her parents, sister and husband, her abilities unappreciated. As Fothergill has observed, ‘the function of the diary is to provide for the valuation of [self] which circumstances conspire to thwart.’[23] Financial circumstances certainly thwarted Kate’s ability to maintain the class position that for some years she had enjoyed, but in her diary she could continue to present herself as an aspiring member of the upper-middle middle class, although, after 1910, always conscious of the financial chasm that existed between this idea of herself and the reality. On March 17th 1913, when meeting her Kensington contemporaries, she notes: ‘They all seemed so smart and so well dressed and so of a different life – the life really that we have left behind. Oh what a difference money makes.’ Lack of money is a recurrent theme, although in her entry for 22 December 1913 she does try to overcome her regrets, writing, ‘I always feel given nice clothes … I could look nice and attractive. I hate being shabby. It is bad enough to grow old, but to grow dowdy with it, but what can one do without money and lots of it. I do seem to grumble. I seem to forget I am aiming for “goodness” in an advanced and suffrage meaning, and that really any other state is very petty.’ It was not that she struck extravagant poses in her diary, rather that there she felt that there her days were being re-enacted in front of an appreciative audience – herself.

Kate seldom dwells on the act of diary writing, but on Sunday 8 February 1914 was prompted to record:

‘I am reading ‘The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff’. It is too absolutely interesting for words – and yet all so natural….it isn’t far off me in the inmost soul. Only in performance she was a genius – she could do – I can only dream that I could and do – accomplish. It made me want to read my old Journals but how tame after Marie’s. I was always for putting time and place and leaving out the really interesting bits in consequence – though I sometimes think I catch atmosphere. That is the disadvantages of writing a diary instead of a Journal – one only ought to write when one is inspired and at the moment the feeling or idea strikes one – but with a diary the date and correctness is the thing.’[24]

Perhaps it is fortunate for us the Kate did not write what she terms a ‘Journal’; it is the ‘putting time and place’ that makes Kate’s diary so interesting.[25] We can sit with her on the tube or bus, travelling around London; we can reconstruct the route taking her from Notting Hill Gate to the Criterion Restaurant in Piccadilly for a meeting of the Actresses’ Franchise League – and then eavesdrop on the proceedings; we can go with her to Covent Garden to see the Russian Ballet – ‘as for M Nijinsky, well, words fail me’;[26] we can travel with her around the country roads of Norfolk, searching out suffrage sympathisers; and accompany her as she organises the transport of her boxes, a complicated business, to and from stations and ‘digs’ in the small towns of east and southern England.

For Kate Frye’s diary keeping makes no distinction between the daily chores – brushing her dog, having lunch, changing her books at Smith’s – and life-changing events. Even so, like all diarists, it is clear that she edited her day and, unsurprisingly, for her diaries had no locks, did not make explicit the details of everything that happened to her. For instance, it was only the reading of an entry in a post-Second World War diary that gave a clue to what lay behind her long association with – and eventual marriage to – John Collins, a fellow actor in the 1903 touring production of Quality Street, a relationship that, as presented in Kate’s words, seems rather puzzling. That post-war entry referred to the one for 20 September 1904, the day that Kate finally agreed to marry John. The entry itself is, naturally, of interest because she is writing of the day of her engagement but, when read in context, is constructed – or self-edited – so as not to include anything particularly revealing, merely that, after some, perhaps rather melodramatic, hesitation, Kate had finally acquiesced to John’s repeated offer of marriage. However, on re-reading the entry in the light of the later comment, a rather different story emerges. Kate’s words – ‘..I had to promise, it is the only right thing left to do …I couldn’t marry anyone else now, as he says. I have burnt my boats and no one must ever know that my real self is hesitating’ – appeared to be those of a woman who had realised that she had to make a decision, that she could no longer keep the man hanging on. But, alerted by the entry written nearly 50 years later, a re-reading reveals a rather different story. For, it transpires Kate had acted in such a way that ensured that, this time, she had to agree to marry John. It is hardly worth speculating on what actually had occurred, although in this entry Kate does write of passion and desire. In fact his lack of money, coupled with her lack of inclination, meant that it was a further 11 years before Kate and John married. Although she often debates with herself as to whether she can continue with the engagement, Kate feels unable to escape what she sees as her obligation. The story of that day in Croydon digs – with the landlady out shopping – is only one, albeit major, episode where the diarist, while ostensibly being frank, has not made all explicit.

There are doubtless very many other such occasions on which the doings of the self as portrayed in Kate’s diary do not reflect exactly the experience of the self that enacted them, the self of the diary having been refashioned by the diarist’s pen. For Kate Frye recognised her diary’s usefulness in providing her with the daily discipline of putting words on paper. Her diary is written in direct, colloquial prose. Her writing is fluent and she makes virtually no corrections. As we have seen, she was interested in ‘catching atmosphere’ and, although she never intended her diary for publication, she did aspire to literary success. Over many years she mentions time spent on ‘writing’ and a quantity of her manuscripts and typescripts, together with the rejection letters from agents and publishers, survive. Unsurprisingly, for one so enamoured of the theatre, these works are all plays, but only a one, co-written with John Collins, was ever published.[27]

Regretting as she did her lack of literary success, it is difficult to believe that she would be averse to seeing her words in print now.

Recognising the affection Kate felt for her diary and the time and care she had spent on shaping it, it is worth considering what she had thought might happen to it after her death. In fact her will reveals that the diaries were in effect her main bequest. She left the many volumes, together with the lead-lined bookcase in which they were kept, itself an indication of the concern she felt for their well-being, to the son of one of her cousins. That cousin, long dead, had been the only one of her relations to have had similar literary aspirations, albeit rather greater success. For, Abbie Frye was a prolific Edwardian novelist who wrote under the name ‘L. Parry Truscott’.[28] Kate had clearly wanted the diaries preserved and had not been worried at the thought of their being read by a member of the younger generation – and, by inference, a later general public. But would she have objected to being presented to the general public only in her role as a suffragist – for that is in effect how she is now re-created?

So let us now view the problem from the other side and consider the contribution that Kate Frye’s diary may make to our understanding of the suffrage movement and of the lives lived by its members. How does Kate’s diary stand among other diaries dealing with the suffrage movement? What makes it worth the trouble of editing and publishing? The main difference between the diary of Kate Frye and most others recording suffrage involvement that survive in the public domain is that the latter were written primarily because that involvement represented a singular experience, a highpoint in the diarist’s life. Thus, for instance, the militant campaign is well represented by diaries kept by imprisoned suffragettes, recording the horrors of forcible feeding.[29] For the constitutionalists, two diaries kept by Margery Lees have survived. Leader of the Oldham NUWSS society, she has recorded in one the work of the society and, in the other, gives an account of her participation in a great NUWSS event, the 1913 suffrage pilgrimage.[30]

Apart from that of Kate Frye, only a handful of other diaries with suffrage-related daily entries are known. Those of the delightfully Pooterish Blathwayts of Batheaston, father, mother and daughter, have proved an excellent source for researchers of WSPU personalities and of the militant campaign in Bath[31] and that of Dr Alice Ker provides short factual notes on the suffrage scene in Birkenhead and Liverpool.[32] The diary of Eunice Murray, a prominent Scottish member of the Women’s Freedom League, is in some ways comparable to that of Kate Frye, although the former’s comments on the suffrage campaign are more measured, while her actual accounts are less detailed.[33] Like Kate, Eunice Murray spoke at suffrage meetings but was not required to organise them and was certainly less concerned with ‘catching the atmosphere’ when writing up her diary entries. The diaries of the actress and novelist Elizabeth Robins (held in the Fales Library, New York) record her involvement with the English suffragette movement but, again, although she contributed as a speaker, she was not working at the suffrage ‘coal face’, as it were. None of these diaries, suffragist or suffragette, has yet been published. Excerpts from the diaries of Ruth Slate and Eva Slawson make clear their interest in the Cause and, interwoven with material from their letters, have been published, but within the overall narrative of their lives and concerns suffrage plays only a relatively minor part.[34]

Kate’s diary is valuable because it records her continuous involvement as a foot soldier in the suffrage campaign. She is writing without the benefit of hindsight, recording the inconsequential details of, say, finding a chairman for a suffrage meeting in Maldon or dealing with an imperious speaker in Dover, as well as the rather more momentous suffrage occasions, such as waiting on the platform at King’s Cross station as the train carrying Emily Wilding Davison’s coffin is about to leave for Morpeth. We can trace day by day, week by week, Kate’s growing participation in the movement, reflecting as it does both the increasing publicity given to and acceptance of the suffrage campaign and the decline in her family’s fortunes.

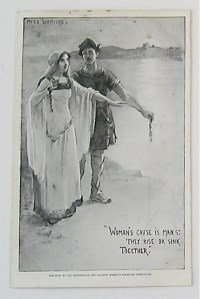

In 1913 Kate was campaigning for the New Constitutional Society in Whitechapel, distributing NCS leaflets translated into Yiddish

Although we cannot say that she became an increasingly militant (although never actively militant)[35] supporter because she regretted her lack of education, in the very first entry in which she refers to suffrage, on 3 December 1906, she writes: ‘I really do feel a great belief in the need of the Vote for Women – if only as a means of Education. I feel my prayer for Women in the words of George Meredith: “More brains, Oh Lord, more brains” ‘[36] – or, again, in 1914, ‘Neither do I understand why I was born if I wasn’t to be educated.’ Kate’s education had been that considered suitable for her gender and class. She did not attend school, but until she was 16 was visited by a ‘daily governess’, although visits were not invariably daily. After that she received somewhat erratic tuition from teachers of French and music. Nor can we say she became a suffragist because she lacked economic power. But she was certainly aware that those two factors – a lack of education and a lack of funds – made life as a woman without the shelter of family money, or the ability to earn her own, very difficult.

Like so many other women at that time, Kate Frye saw the acquisition of the vote as one step towards autonomy. It is our luck that for a few years she attempted to solve her economic problem by propounding the political solution, that is, she earned a living, of sorts, by becoming a suffrage organiser. It is extra fortunate that she did so for a society, the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage, about which very little has hitherto been known. In fact Kate Frye’s diary contains more information about the NCSWS and more of the society’s ephemera than exists anywhere else.

Her elaboration of diary entries by the addition of leaflets advertising the suffrage meetings she attended, even on occasion leaflets she herself had arranged to have printed, and for the processions in which she took part, demonstrates how prominently the campaign figured in her life. Virtually no other ephemeral material is included during this period.

We need only look to the diary for the answer to the question as to whether Kate Frye would object to being remembered as a suffragist. For on ‘Sunday 10 February 1918’ she wrote, ‘One of my afternoon letters was to Gladys Simmons[37] in commemoration of the passing of the Franchise Bill. Haven’t had a single letter from anyone concerning it – I said I wouldn’t but it seems very strange – that someone hasn’t thought of me in connection with the work.’ Now that her suffrage diary is published, at last Kate Frye will ‘be thought of in connection with the work’ and be recognised as a suffragist.[38] However, the very act of publication highlights just this one of her many roles. Out of the multiplicity of Kate Frye’s self-constructions, it is the ‘self’ of her suffrage years that emerges. The reader will have to accept that ‘mining’ a diary in order to view an historical episode from a fresh angle may come at the expense of maintaining the integrity of the diarist’s conception of ‘self’.

Kate’s diary entry for 21 May 1914 in which she records witnessing the WSPU demonstration in front of Buckingham Palace

[1] Katharine Parry Frye (1878-1959), daughter of Frederick and Jane Kezia Frye. Frederick Frye was a director of a chain of licensed grocery shops, Leverett and Frye, a firm financed by the wine merchants W.& A.Gilbey, as a useful outlet for their wines. When Frederick Frye became an M.P., Gilbey’s took over the running of the business. The Irish branch still operates. Frederick’s father had been a ‘professor of music’ and for 64 years organist at Saffron Walden parish church. Jane Frye’s father was a Winchester grocer. In 1915 Kate married John R. Collins.

[2] In August 2010 correspondence on Guardian Online, which included contributions from members of the Women’s History Network, demonstrated that it is by no means unusual for contemporary women to keep daily diaries over decades of their lives..

[3] Kate’s Aunt Agnes (1834-1920, née Crosbie), her mother’s sister, was the widow of Alfred Gilbey (d. 1879). For details of the Gilbeys of Wooburn House, Wooburn, Buckinghamshire see B. B. Wheals (1983) Theirs were but human hearts: a local history of three Thameside parishes (Bourne End: H.S. Publishing). From their relatively humble origins the brothers Walter and Alfred Gilbey grew wealthy as they developed England’s largest wine merchant business, W. & A. Gilbey.

[4] ‘Accounts and Legal’, Quality Street tour accounts (Theatre Museum), cited in Tracy C. Davis (2000) The Economics of the British Stage 1800-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) p.217.

[5] For a discussion of the entrance of middle-class women into the acting profession see Tracy C. Davis (1991) Actresses as Working Women (London: Routledge) pp. 13-16.

[6] In the 1920s and 1930s Kate often joined her husband on tour. For instance, over many years she spent some time each year at Stratford-on-Avon, where her husband was stage manager for productions at the old Memorial Theatre.

[7] Agnes Frye (1874-1937)

[8] See T. Mallon (1995) A Book of One’s Own: people and their diaries (St Paul, Minn: Hungry Mind Press) p. 1.

[9] Robert A. Fothergill (1974) Private Chronicles: a study of English diaries (London: OUP).

[10] See Jane DuPree Begos (1977) Annotated Bibliography of Published Women’s Diaries (issued by the author); Margo Culley (Ed) (1985) A Day at a Time: the diary literature of American women from 1764 to the present day (Old Westbury NY: Feminist Press); Harriet Blodgett (1989) Centuries of Female Day: Englishwomen’s Private Diaries (New Brunswick, London: Rutgers University Press); Cheryl Cline (1989) Women’s Diaries, Journals and Letters: an annotated bibliography (New York and London: Garland Publishing); Harriet Blodgett (Ed.) (1992) The Englishwoman’s Diary (London: Fourth Estate); Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia A. Huff (1996) Inscribing the Daily: critical essays on women’s diaries (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press) Suzanne L. Bunkers (2001) Diaries of Girls and Women: a midwestern American sampler (London, University of Wisconsin Press).

[11] Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia Huff ‘Issues in Studying Women’s Diaries: a theoretical and critical introduction’, in Bunkers and Huff (Eds) Inscribing the Daily, p.1

[12] Sir Arthur Ponsonby (1923) English Diaries (London:Methuen & Co), p. 5.

[13] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p. 5

[14] Cline, Women’s Diaries, p xxvii-xxviii.

[15] Exceptions include Bunkers, Diaries of Girls and Women. See also Cynthia Huff (1985) British Women’s Diaries: a descriptive bibliography of selected 19th-century women’s manuscript diaries (New York: AMS Press).

[16] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p. 5.

[17] Cline, Women’s Diaries, p. xxviii.

[18] L. Woolf (Ed) (1953) A Writer’s Diary. Being extracts from the diary of Virginia Woolf (London, Hogarth Press).

[19] Although, after Leonard Woolf’s ‘dismembering’, the diaries were reconstructed, in five volumes, edited by Anne Olivier Bell.

[20] For instance, Martin Hewitt (2006) Diary, Autobiography and the Practice of Life History in David Amigoni (Ed) Life Writing and Victorian Culture (Aldershot: Ashgate).

[21] Huff, British Women’s Diaries, p xiv.

[22] Whiteleys was a large department store, which, when Kate wrote this 1913 entry, was in Queensway. The store’s owner, William Whiteley, ‘the Universal Provider’, had been a close friend of the Frye family and his murder and subsequent trial are recorded in detail in Kate’s 1907 diary.

[23] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p.82.

[24] .Marie Bashkirtseff, a young Frenchwoman, filled 85 notebooks with her journal, which was edited for publication after her death in 1884. An English edition, Mathilde Blind (Ed. and Trans) 1890, The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff (London: Cassell) 2 volumes. Philippe Lejeune has described the Journal as foreshadowing ‘a line of diaries where introspection, active contestation of the condition of women, and interest in writing stand out as defining features’, see Philippe Lejeune The “Journal de jeune fille” in Nineteenth Century France in Bunkers and Huff, Inscribing the Daily, p119.

[25] Some attention has been paid to this distinction by scholars of diary writing. Suzanne Bunkers, after initially believing that what distinguishes a journal from a diary is that the diary is ‘a form of recording events, and the journal is a form of introspection, reflection, and the expression of feeling’, comes to the conclusion that the distinction is untenable, see S. Bunkers, Diaries of Girls and Women, p 12.

[26] Diary entry for 9 July 1912.

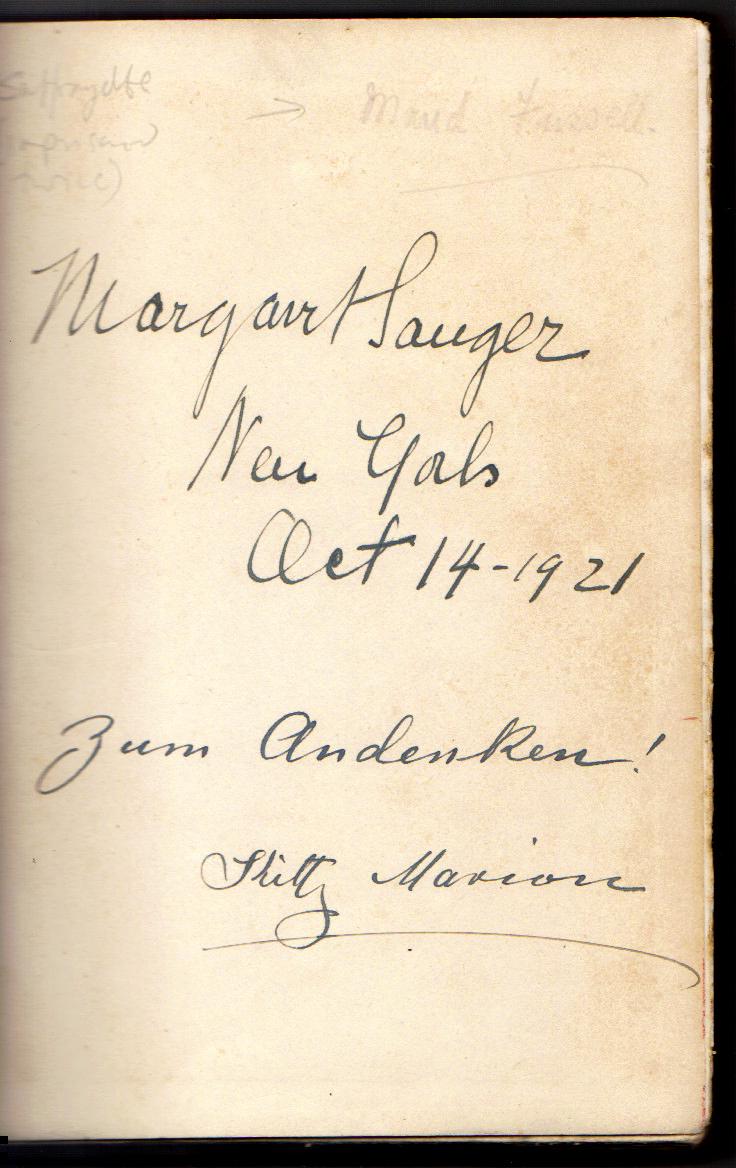

[27] Katharine Parry and John R. Collins (1921) Cease Fire!: a play in one act (London: French’s Acting Editions).

[28] Gertrude Abbie Frye (always known as Abbie), later Mrs Basil Hargrave (1871-1936). The works of ‘L. Parry Truscott’ were mistakenly attributed to Katharine Edith Spicer-Jay in Halkett (1926) Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous English Literature, (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd), Vol 1. By 1926 ‘L. Parry Truscott’’s star had waned and Abbie, by now a widow, was vitually penniless. A considerable amount of information about the interesting life of Abbie Frye can be gleaned from Kate Frye’s diary.

[29] See the manuscript prison diaries of Mary Anne Rawle, Elsie Duval and Katie Gliddon (Women’s Library); the manuscript prison diaries of Olive Walton and Florence Haig (Museum of London); and the manuscript prison diary of Olive Wharry (British Library); The manuscript prison diary of Anne Cobden Sanderson (London School of Economics) has been edited by Anthony Howe but is, as yet, unpublished.

[30] Both Margery Lees’s diaries are held by the Women’s Library.

[31] The Blathwayt diaries are held in the Gloucestershire Record Office. See June Hannam ‘Suffragettes are Splendid for Any Work’: the Blathwayt Diaries as a Source of Suffrage History in Clare Eustance, Joan Ryan and Laura Ugolini (Eds.) (2000) A Suffrage Reader: charting directions in British Suffrage History (London: Leicester University Press).

[32] Dr Alice Ker’s diaries are held in a private collection.

[33] The manuscript of Eunice Murray’s diary are held at the Women’s Library, together with a bound copy of the Diary of Eunice Guthrie Murray, transcribed by Frances Sylvia Martin.

[34] T. Thompson (Ed.) (1987) Dear Girl: the diaries and letters of two working women (1897-1917) (London: Women’s Press).

[35] Kate Frye joined the WSPU in November 1910, after witnessing the ‘Black Friday’ demonstration, but was soon appointed as a paid organiser for the newly-formed New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage.

[36] The quotation is taken from Modern Love by George Meredith, first published in 1862.

[37] As Gladys Wright, she had been a very old Kensington friend of Kate Frye and hon. Sec. of the NCSWS.

[38] Campaigning for the Vote: The Suffrage Diary of Kate Parry Frye, is published by Francis Boutle

Campaigning For The Vote: Kate Frye and Knightsbridge

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on April 29, 2013

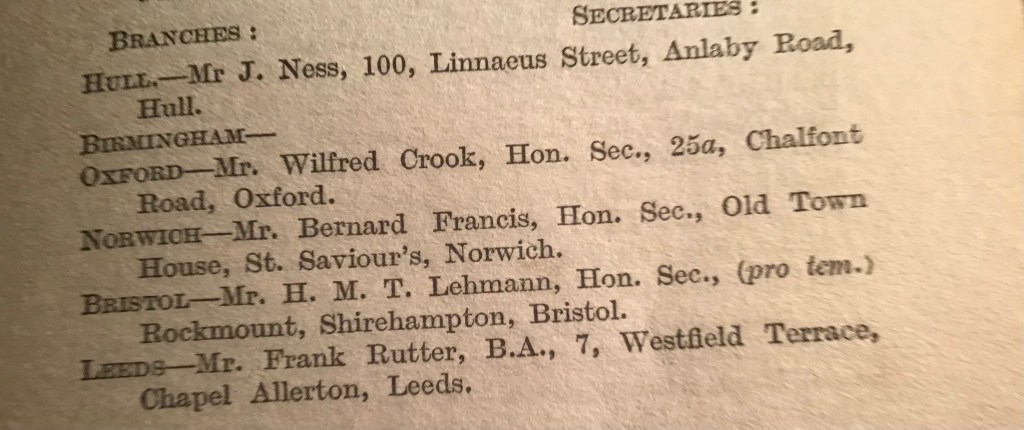

In early 1911 Kate Frye took up her position as a paid organizer for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. The Society had been founded in January 1910 to take a position between that held by the militant Women’s Social and Political Union and the ‘constitutional’ National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Although its members did not want to break the law themselves, the NCS did not condemn WSPU tactics and supported its policy of campaigning against government (Liberal) candidates at elections, thinking the NUWSS had become too ineffectual.

In early 1911 Kate Frye took up her position as a paid organizer for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. The Society had been founded in January 1910 to take a position between that held by the militant Women’s Social and Political Union and the ‘constitutional’ National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Although its members did not want to break the law themselves, the NCS did not condemn WSPU tactics and supported its policy of campaigning against government (Liberal) candidates at elections, thinking the NUWSS had become too ineffectual.

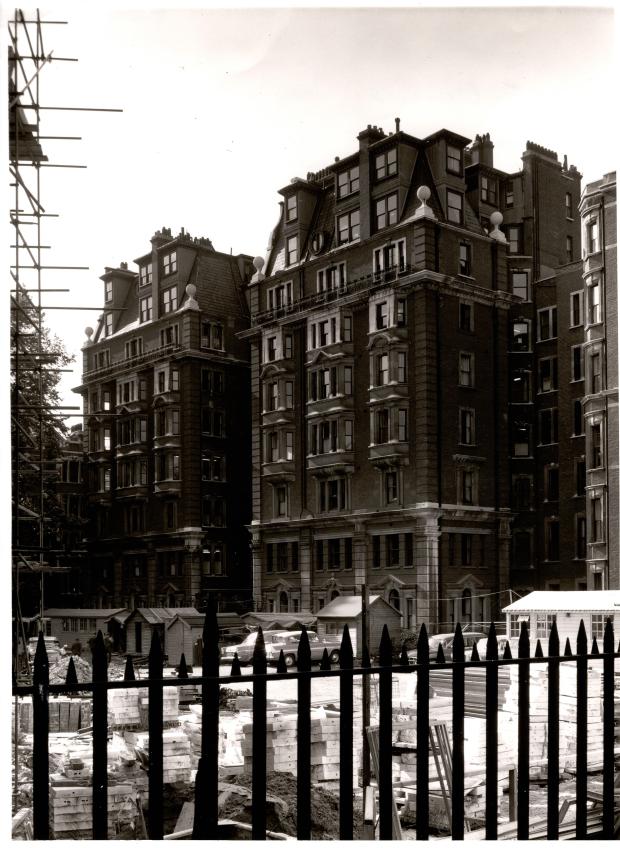

Unlike the other main suffrage societies that had their offices either around the

Holborn/Strand area or in Victoria/Westminster, the NCS took up residence in Knightsbridge. They rented an office in Park Mansions Arcade which ran through a relatively newly-built block of mansion flats between Knightsbridge and Brompton Road. The shop area at street level is now occupied by a major Burberry store, into which the Arcade has, at some time in the past, been incorporated. The Arcade part now houses a recently created Burberry Menswear department. To see today’s glamorous reality and to imagine Kate and her co-workers at the NCS walking through this space – full of thoughts of converting the women – and men – of Britain to the Cause – click here.

Knightsbridge was an area that would have appealed to members of the NCS, many of whom lived in Kensington and Paddington. Many of these women had belonged to the London Society for Women’s Suffrage (NUWSS), but had become disenchanted with what appeared to be lack of progress, although were not quite prepared to go so far as to join the militants. However, you can see from the entertainments offered at the opening of the Park Mansions Arcade Office, that members of the WSPU and the Actresses’ Franchise League lent their support.

Campaigning For The Vote: Kate Frye In ‘Spitalfields Life’

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on April 19, 2013

Kate and her Suffrage Diary have been given most generous coverage in that most admirable of blogs

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – e.crawford@sphere20.freeserve.co.uk (£14.99 +UK postage £3. Please ask for international postage cost), or from all good bookshops. In stock at London Review of Books Bookshop, Foyles, National Archives Bookshop.

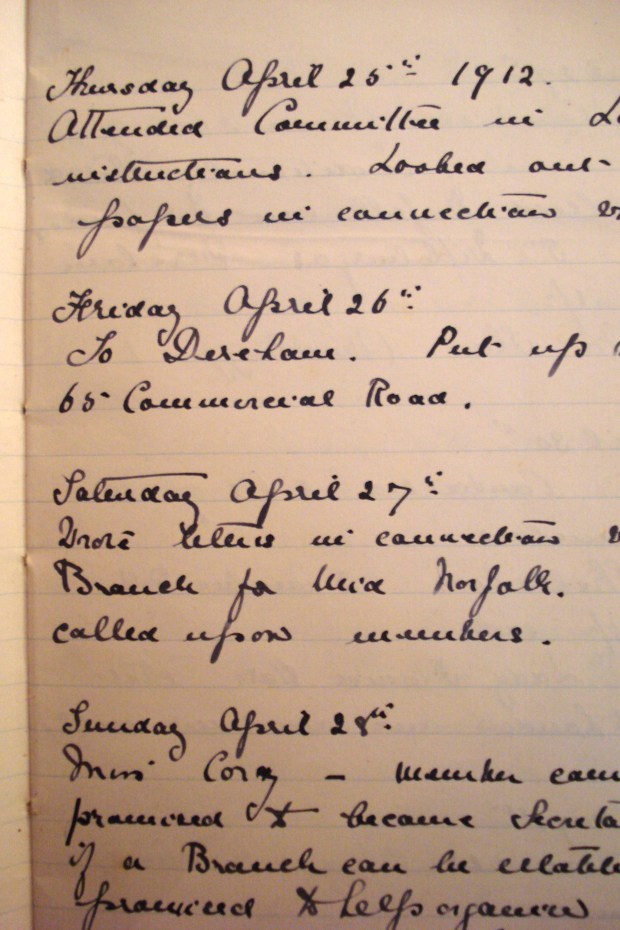

Campaigning For The Vote: Kate In Norfolk: East Dereham

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on April 18, 2013

Between 1911 and 1914 Kate Frye spent over 20 weeks organising the New Constitutional Society for Women Suffrage’s campaign in Norfolk. For the greater part of that time she was based in East Dereham.

Between 1911 and 1914 Kate Frye spent over 20 weeks organising the New Constitutional Society for Women Suffrage’s campaign in Norfolk. For the greater part of that time she was based in East Dereham.

In Campaigning for the Vote entries – such as these samples below relating – at random – two days in Kate’s Norfolk experience – are fully annotated, giving biographical details of most of the people she mentions. Thus Kate’s diary is of interest to local historians over and above the light it sheds on the suffrage campaign in the area. For instance, ‘Miss Cory’ was Violet, daughter of the London and Provincial bank manager. The Corys lived above the bank, now Lloyds TSB and still there at 38 Market Place. For a most interesting tour around Dereham’s Market Place – an area with which Kate became intimate – see here.

Tuesday March 25th 1913 [lodging at 63 Norwich Street, East Dereham]

Most of the day spent in hunting about for rooms for Mrs Mayer with no success – even the Kings Head refused to have her. Canvassing and bill distributing – beginning, as usual, to feel anxious about the success of next Monday’s meeting. Changed and out at 4 to Miss Cory’s to tea. I went to call on Mrs Pearse when I left there and saw Mr Pearse and asked him to take the Chair but he would none of it. We had all been so ‘naughty’ etc and of course the destruction of the golf links had been the last straw. He is a pasty-faced Villain. But I wish he would take the Chair for us because if he does not I don’t know who will and I shall have to do it – the very idea curdles my blood.

On 10 March 1914 a WSPU member, Mary Richardson, attacked the Velasquez painting, ‘Venus with a Mirror’, hanging in the National Gallery, in order to draw attention to what she saw as the slow destruction of Mrs Pankhurst, who had, on 9 March, yet again been arrested.

Wednesday March 11th 1914 [lodging at 3 Elvin Road, East Dereham]

Miss Cory here at 10.30 and we went through the people I am to call upon. Out 12 to 1. To see Miss Shellabear. Very off, of course, the latest – the Rokeby Velasquez – is upsetting everyone now. Out 2.45 to 6.15. Calls.

Happened on the new people at Quebec Hall who are keen WSPU. Had tea with Miss Louisa Gay who has done 8 months [in prison]– a very jolly girl – she means to do some waking up if she can. Then to see Mr and Mrs Hewitt – I do like them so. Miss Cory and Mrs Goddard here 8 to 10. Talking. Talking. Talking.

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – e.crawford@sphere20.freeserve.co.uk (£14.99 +UK postage £3. Please ask for international postage cost), or from all good bookshops. In stock at London Review of Books Bookshop, Foyles, National Archives Bookshop.

Campaigning For The Vote: Kate In Kent: Folkestone

Posted in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on April 17, 2013

In the course of the years 1911-1914 Kate Frye spent over 20 weeks organising the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage’s campaign in Kent. She recorded every detail of her daily life in the entries she made in her diary and a selection, relating to the conduct of the campaign, are included in Campaigning for the Vote.

In the course of the years 1911-1914 Kate Frye spent over 20 weeks organising the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage’s campaign in Kent. She recorded every detail of her daily life in the entries she made in her diary and a selection, relating to the conduct of the campaign, are included in Campaigning for the Vote.

Kate spent time in Ashford, Folkestone, Hythe and Dover, canvassing house-by-house and organising meetings in drawing-rooms and public halls.

Below are three samples of Kate’s Folkestone experiences.

Saturday October 21st 1911 [Folkestone: 4 Salisbury Villas]

Quite a mild day and needed no fire till evening but inclined to shower. I wrote letters – then at 11 to Mrs Kenny’s – 63 Bouverie Road, Folkestone.

She had asked me to lunch but Mrs Hill wanted me back again so, as there wasn’t much I could do, I just had a chat with her and Mrs Chapman, who is staying there, and came back again. Changed and got back to Mrs Kenny’s at 2.30 for her party at 4. Miss Lewis of Hythe took the Chair and Mrs Chapman spoke. There were between 70 and 80 people – mostly very smart – a military set. Mrs Kenny is very nice and Colonel Kenny is quite sweet. Some of the men were very amusing. I got a golf ball from one and sold it for 2/6. And got one young officer to buy The Subjection of Women. There was a most gorgeous tea, which no-one hardly touched. Mrs Hill and I walked home together – got in about 6.30. Another evening of gabbling chat and to bed about 10 o’clock. She is very nice but so intellectual. I feel sorry for the child. A most terrific gale raged all night. I thought the house must be blown in.

Kate spent two weeks in Folkestone on that occasion, returned for another two in February 1912 and that autumn spent a further three weeks attempting to galvanise the Kent campaign into a semblance of life.

Saturday October 5th 1912 [Folkestone: 33 Coolinge Road]

In my morning of calls, I only found two people at home. At 12.30 I gave it up. I did feel depressed. More so when, having met Mrs Kenny at the Grand Hotel at 3.30, where she was attending a wedding reception of a Miss Cooper, and whose good-byes I just came in for, Mrs Kenny and I called together upon the manager’s wife, Madame Gelardi, and to my horror I found that her husband would not contemplate for a moment letting us have a Suffrage At Home in the reception room. Well that does put the lid on things.The time is slipping away here – the days fly, I love the place and am very comfortable in my rooms but I cannot seem to work here and I feel utterly miserable about it.

Kate’s mention – in the entry below – of ‘this split’ refers to the announcement Mrs Pankhurst had made on 17 October at an Albert Hall meeting that the Pethick-Lawrences were no longer involved with the WSPU. The Pethick-Lawrences’ departure had been unilateral. Lady Irving was the – long-estranged – widow of the actor, Sir Henry Irving

Tuesday October 22nd 1912 [Folkestone: 33 Coolinge Road]