On 7 August 2014 ITV will publish an e-book, Kate Parry Frye: The Long Life of an Edwardian Actress and Suffragette. Based on her prodigious diary, this is my account of Kate Frye’s life and is a tie-in with the forthcoming ITV series ‘The Great War: The People’s Story’. For details of the TV series and its accompanying books see here.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

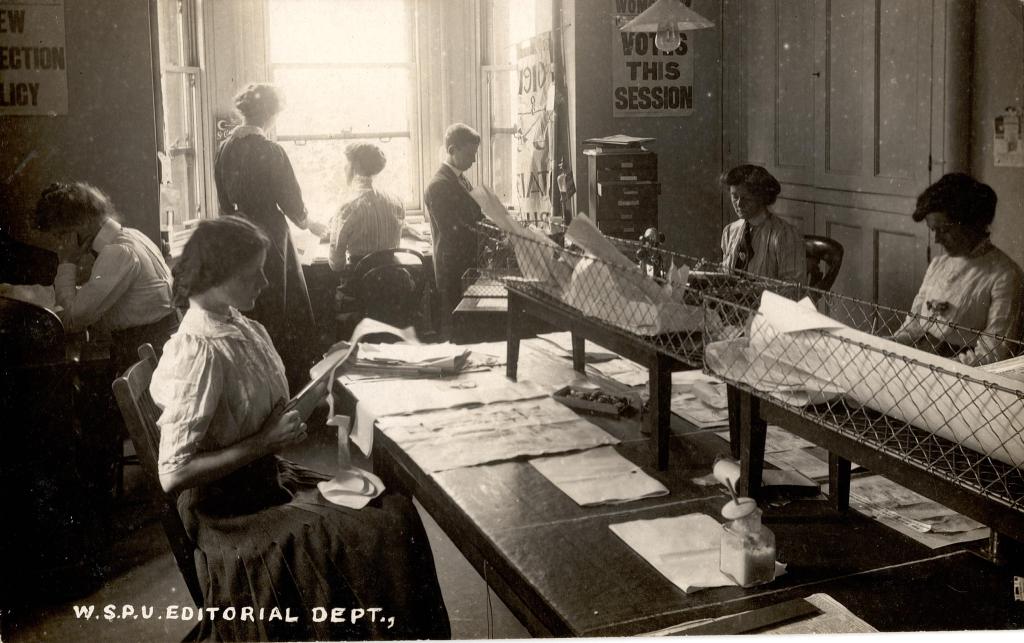

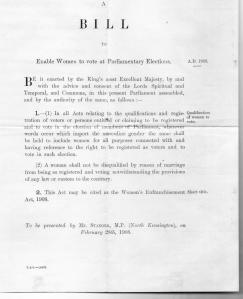

Kate was at this time 36 years old, living in a room at 49 Claverton Street in Pimlico and working in the Knightsbridge headquarters of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was now nine years since she had become engaged to (minor) actor John Collins. Her father died in March 1914 and her mother and sister, Agnes, now all but penniless, are living in rented rooms in Worthing. John has a room along Claverton Street, at number 11.

Friday July 17th 1914

John arrived unexpectedly early, before I was up, but I just let him in to hear the news – he has had a letter from Benson saying he would see him, so was off. I had received a letter from Mr Dingle saying he could not speak – so as soon as I was up I went off to the Men’s League at Westminster and saw someone there who called Mr McKillop in from an office next door, and he like a lamb said he would come to Isleworth in Mr Dingle’s place. I expected to have to rush round London.

So I walked up to the A.A. and found John just having lunch with a very pretty woman and joined them as I wanted to hear what Benson said, but it was a very short interview. John saw me to Charing Cross then went off to a meeting and I came back to Victoria and bought some food then came in and had a rest and fell asleep.

John came in at 5 and we had a meat tea and then off together, Bus to Victoria – train to Hammersmith – train to Isleworth arriving at 7.15 – at the Upper Square. There were hundreds of children ready to greet us, I got a friendly feeling and they were very good but a great nuisance. John went off to find the Lorry as it was not punctual, but he missed it and it arrived alright and I got it fixed up.

By the time the speakers, Miss Dransfield in the Chair, Mrs Merivale Mayer and Mr McKillop and Miss Fraser to help had arrived we were absolutely mobbed – and we got a huge gathering. The first Suffrage meeting of any kind which had been held in Isleworth.

Mrs Mayer as usual was very disagreeable when she arrived, but it was really such a magnificent meeting she was quite pleased at the end, and as usual she spoke splendidly and we quite got the people round.

Having settled up early well came away together – Mr McKillop left us from the train, we parted from Mrs M.M. at Hammersmith and Miss Fraser at Victoria.

John and I were starving and we went into a restaurant at Victoria. John had salmon and cucumber – at 11.15! It was a lovely day.

John Collins was ‘resting’ at the moment – as is clear from the amount of time he was able to devote this month to helping Kate with her suffrage work. He would have been very excited about the prospect of employment in Frank Benson’s Company. The A.A., where Kate surprised him lunching with ‘a very pretty women’, was the Actors’ Association, the club in Covent Garden to which they both belonged.

The Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage to whose office Kate went for help when her speaker had failed was at 136 St Stephen’s House on the Embankment. The massive building was demolished, apparently in the early 1990s. We have already met the obliging Mr McKillop, who had for some years earlier been librarian to the fledgling London School of Economics. Kate had warmed to him after he praised her public speaking.

Well, this must have been the site of Isleworth’s first ‘Votes for Women’ meeting – or, at least, the first of which Kate had heard tell. Presumably during her canvassing she had met with plenty of local people who would have given her this kind of information. By ‘fixing up’ the Lorry Kate meant that she decorated it with posters – inquisitive children were suffragettes’ constant companions.

You can read about Mrs Merivale Mayer in Campaigning for the Vote – suffice it to say that Kate found her a great trial and, I am sure, knew nothing of her somewhat scandalous history. If she had known she would doubtless have felt vindicated in her dislike for this most difficult of the New Constitutional Society’s speakers. But Kate gave credit where it was due and often commented, as she does here, that despite the ructions she caused Mrs Mayer was an excellent speaker.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.