Woman and her Sphere

Posts Tagged sylvia pankhurst

Suffrage Stories: Murder, Suicide, and Dancing: Or What Might Have Brought Mrs Pankhurst to 62 Nelson Street?

Posted by womanandhersphere in Suffrage Stories on March 31, 2021

I hope those acquainted with my website will also be aware of the existence of the Pankhurst Centre in Manchester. If so, you will know that the Centre comprises two houses, 60 and 62 Nelson Street, the only buildings from the original early 19th-century street still standing, surrounded by the ever-expanding complex of Manchester Royal Infirmary. That the adjoining villas, built c 1840, are still there is due only to the fact that it was at number 62 in October 1903 that Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst founded the Women’s Social and Political Union. The buildings were listed Grade 2* in 1974 to save them from demolition.

Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst and her children, Christabel, Sylvia, Adela, and Harry moved into 62 Nelson Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, in the autumn of 1898. Her husband, Dr Richard Pankhurst, had died in the summer, on 5 July, leaving very little money, and his family was forced to economise by moving from their home, 4 Buckingham Crescent, Daisy Bank Road, Victoria Park, into a property cheaper to rent.

Mrs Pankhurst could have moved to any area of Manchester, so why was 62 Nelson Street chosen as the new family home?

In 1894 Mrs Pankhurst had been elected to the Chorlton Board of Guardians as a Poor Law Guardian, an unpaid position. Now, in the summer of 1898, she had to earn enough to support herself and her family and so on 30 August she resigned and, instead, accepted the offer made by the Board of Guardians of the post of salaried registrar of births, marriages, and deaths for Chorlton-on-Medlock.

Chorlton had been urbanized in the early 19th c, when streets of terraced houses were built to house the workers required to operate the large mills newly erected alongside the River Irwell. It was an area very much less salubrious than Victoria Park, but Nelson Street, off Oxford Road, was more refined than most surrounding streets. It was also a street that was well-known to the two eldest Pankhurst daughters.

I have never seen any mention in Pankhurst biographies and autobiographies of this apparent coincidence, but it was at number 60 that Christabel and, I think, Sylvia, had been regular visitors, students at the dancing school run by Mrs W. Webster and her brother. Although the name of the dance teachers does appear in Sylvia Pankhurst’s The Suffragette Movement, she makes no mention of the school’s address. Sylvia wrote:

‘We learned dancing from the Websters, an old dancing family in Manchester, and Christabel, who hitherto had never cared much or long for anything, roused herself to unexpected efforts to excel everyone in the class’. Sylvia suggests that Christabel, whom her mother intended should be a dancer, had taken lessons for several years before becoming ‘suddenly tired of the project’ around the time she was 16, that is in 1896.

In the years between 1890 and 1896 the dancing academy was run by Mrs W. Webster and her brother. Until his early death in 1890 the dancing master had been William Hilton Webster and the school had then been continued by his widow. She was Ellen Marianne Webster (née Goodman), who had been a cousin to her husband. For reasons that are unclear, her brother, Archie, changed his name from Goodman to Webster, perhaps to capitalize on the ‘Webster’ name, which, as Sylvia suggests, had long been synonymous in Manchester with ‘dance’, as William Hilton Webster’s father had been a dance teacher there from the 1870s. William Webster had moved to 60 Nelson Street in 1884, taking over the premises and goodwill of another dancing master, ‘Monsieur Paris’.

Christabel would have been taught by either or both Ellen and Archie Webster. The lessons offered were not for ballet dancing, but general classes for ballroom dancing and private classes for waltz, skirt,and serpentine dancing. Although I have no evidence, it strikes me that it must have been the latter types of semi-burlesque dance that, according to Sylvia, Mrs Pankhurst hoped Christabel would – as’ a professional devotee of Terpsichore’ – perform in the great cities of the world. A studio photograph of Christabel posed, with pointed foot, holding up with both hands material from her long, flowing dress, is exactly illustrative of a skirt dance. It was taken in Geneva in the summer of 1898 and is reproduced in June Purvis’ biography of Christabel.

Widowed Ellen Webster had four young children, two boys and two girls, and in 1893 remarried, her second husband being Charles Joseph Rourke, a cotton waste merchant. It was presumably during the next couple of years or so that Christabel and, perhaps, Sylvia were attending classes. They may still have been doing so when, in October 1895, 60 Nelson Street hit the headlines in newspapers around the country. Ellen Webster had committed suicide, murdering the elder of her sons at the same time. She had poisoned herself and both sons, but the younger recovered. Her daughters were at a boarding school in Sale, Cheshire, and although she had sent a servant to bring them home, apparently with the idea of killing them as well, their arrival was delayed, and they were saved. The inquest returned a verdict of murder and suicide, due to temporary insanity. The funeral of poor Ellen Webster and her son was held at St Aloysius Church, Ardwick, where she had been married a couple of years earlier.

Thus, in 1898, when Emmeline Pankhurst was looking for a house to rent, she would have been well acquainted with Nelson Street, not only as the address of the dancing school that her daughters had attended but as the site of a very recent Manchester tragedy.

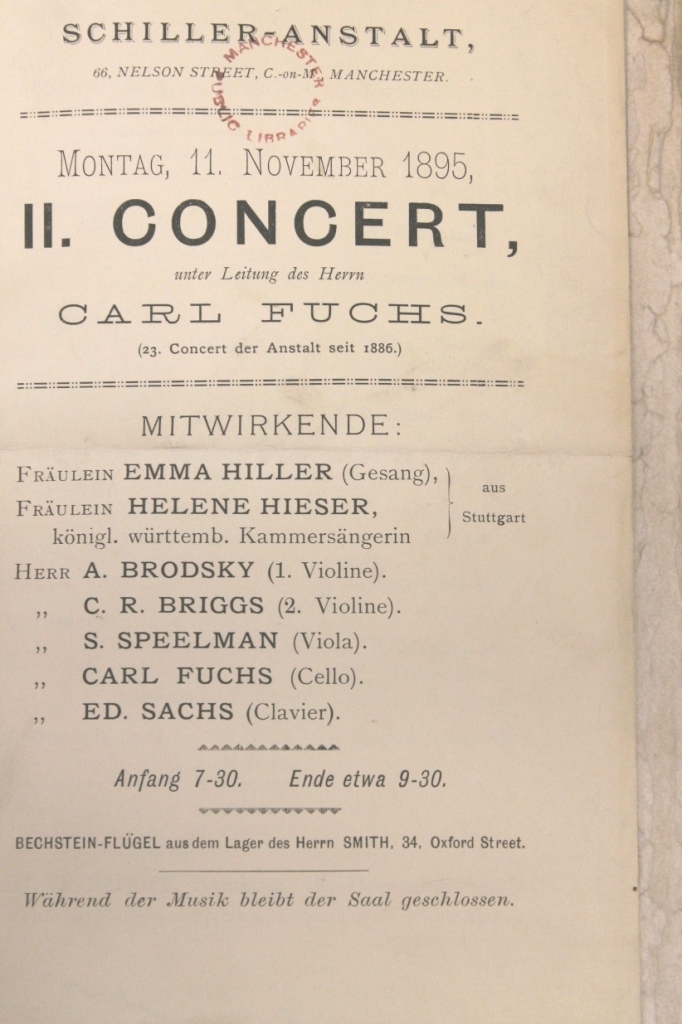

Besides the dancing school Nelson Street contained another cultural centre at number 66 – the Schiller Anstalt Institute – a centre for the large Manchester German community. The Institute was housed in a building that had been converted from domestic use in 1886 and now offered a concert hall and gymnasium, holding a regular programme of lectures and musical activities [For more information about the Institute see here.] The Institute did not close until 1911 and it may well be that, as it was so close by, members of the Pankhurst family did occasionally attend an event there.

Between number 62 Nelson Street and the Schiller Anstalt Institute, number 64 was a large, detached house, once the home of a mayor of Manchester, but now, known as Nelson House, run as a private nursing home. This may explain why, when, previously, number 62 had been advertised for rent it was deemed ‘suitable for a medical man’.

Number 62 was described as offering ‘Three entertaining rooms, five bedrooms, dressing room, bath, w.c. and well-appointed domestic offices’, large enough for Emmeline to devote one room (presumably one of the ‘entertaining rooms’), as her registry office. The bedrooms were under pressure on the night of the 1901 census, for sleeping in the house were Emmeline and her four children, together with her two brothers, Walter and Herbert Goulden, the latter’s son, and the family’s two servants, the cook, Ellen Coyle (of whom Sylvia speaks very fondly) and Mary Leaver, the housemaid. I imagine that the Pankhurst children were made to share rooms, but presumably that was unusual and, now ranging in age from 20 to 11, they normally had a little more space to themselves. It’s difficult to imagine Christabel and Sylvia being happy to share, but doubtless on occasion they were forced to.

The situation only eased in the autumn 1904. Mrs Pankhurst placed an advertisement in the Daily News, ’Wanted, for art student. One or two Rooms, furnished or unfurnished. Near South Kensington Museum. Terms Moderate.’ The reply address was ‘Pankhurst, 62 Nelson Street, Manchester.’ Sylvia was off to London, to study at the Royal College of Art, freeing up a bed in the family home.

In October 1907 advertisements for 62 Nelson Street once more appeared in the press, in the Manchester Courier, indicating that the house was again to let. Emmeline Pankhurst, who had formed the Women’s Social and Political Union in the kitchen just four years earlier, had already left for London to join her daughters, Sylvia and Christabel, who had brought the fight for the vote to the capital.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement

Christabel Pankhurst, emmeline pankhurst, pankhurst centre, schiller anstalt institute, sylvia pankhurst

Collecting Suffrage: The WSPU Holloway Prison Brooch

Posted by womanandhersphere in Uncategorized on August 13, 2020

The Holloway Prison brooch was designed by Sylvia Pankhurst and awarded to members of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) who had been imprisoned. It was first mentioned in the WSPU paper, ‘Votes for Women’, on 16 April 1909 and was described as ‘the Victoria Cross of the Union’. [It pre-dated the Hunger-Strike medal]. The design of the brooch is of the portcullis symbol of the House of Commons, the gate and hanging chains are in silver, and the superimposed broad arrow (the convict symbol) is in purple, white and green enamel. The piece is marked ‘silver’ and carries the maker’s name – Toye & Co, London, who were also responsible for the hunger strike medals. This brooch is for sale. Such treasures of the suffrage movement are now very scarce. It is in fine condition.

SOLD

Email me if you are interesting in buying. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

Suffrage Stories: Words – As Well As Deeds

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage, Suffrage Stories on May 7, 2014

This article was published in the March 2003 issue of Antiquarian Book Review.

‘Deeds Not Words’ was Mrs Pankhurst’s motto. The slogan flourished in the early 20th century – it was even embroidered on a banner – a reaction to the apparently unproductive campaign for the enfranchisement of women that had already been waged for nearly 40 years.

The debate as to whether the vote was won by the slow drip of reasoned argument or by the sharp crack of breaking glass is one that still occupies historians. Although it is the deeds of Mrs Pankhurst’s suffragettes – the spectacle of processions, the breaking of windows, the burning of houses and churches – that has coloured the popular perception of the suffrage campaign, without the ‘words’ that had over many years shaped the idea that women had an equal right with men to citizenship, the ‘deeds’ would have been committed in a vacuum. The women’s suffrage campaign was, during its entire 62 years, underpinned by ‘Literature’ in all its guises.

The debate as to whether the vote was won by the slow drip of reasoned argument or by the sharp crack of breaking glass is one that still occupies historians. Although it is the deeds of Mrs Pankhurst’s suffragettes – the spectacle of processions, the breaking of windows, the burning of houses and churches – that has coloured the popular perception of the suffrage campaign, without the ‘words’ that had over many years shaped the idea that women had an equal right with men to citizenship, the ‘deeds’ would have been committed in a vacuum. The women’s suffrage campaign was, during its entire 62 years, underpinned by ‘Literature’ in all its guises.

Works written in support of women’s enfranchisement had little difficulty in achieving publication. The instigators of the movement were members of the articulate radical middle class and were in close contact with communicators. A tentative beginning had been made in 1851 with Harriet Taylor’s article The Enfranchisement of Women, which, shortly after her marriage to John Stuart Mill, was published anonymously in the Westminster Review ( a journal of which Mill had in the past been editor). This was followed in 1855 by a pamphlet, The Right of Women to the Elective Franchise, written by Agnes Pochin, wife of a future Liberal MP, and published by John Chapman, that ‘Publisher of Liberalisms’.

Among the names of the 1500 women who signed the suffrage petition that Mill presented to parliament in June 1866 (marking the formal beginning of the campaign), were several with connections to the publishing or bookselling trades – including Elspet Strahan, sister of Alexander Strahan, a liberal with a zeal for social reform and the publisher of the eponymous publishing house. He had recently launched the Contemporary Review, in which he published an article on ‘female suffrage’ in March 1867, written by Lydia Becker.

Based in Manchester, Lydia Becker was to be the driving force behind the 19th-century campaign. Among other signatories to the petition were Louisa Farrah, wife of a radical publisher and bookseller (282 Strand, London); Eliza Embleton, a bookseller from Leeds (Burley Street); the wife of James Renshaw Cooper, a radical Manchester bookseller (1 Bridge Street); and the wife and daughter (both named ‘Harriet’) of Edward Truelove, radical publisher and antiquarian bookseller (2240 Strand), who had been imprisoned for publishing Robert Owen’s Physiology in Relation to Morals. (See here for an interesting blog by Dr Tony Shaw about Truelove and his grave, on which the two Harriets both appear.)

Once the campaign had been launched, ‘words’ in support of women’s enfranchisement multiplied rapidly. The societies that had formed to promote the cause published a plethora of pamphlets – one of the first, of which 4500 copies were distributed, was a reprinting of the speech made by Mill to Parliament during the debate on the second reform bill in May 1867.

The accounts of the earliest Enfranchisement of Women Committee show that in its first year of existence over £94 was spent on printing. This was set against receipts from the sale of pamphlets of only £6 11s. Political publishing was not a profitable business. In reality, political publishers who were prepared to put their imprint on books and journals to promote the woman’s cause were not so unworldly as to risk their money. A study of the ledgers of companies, such as Trubner and H.S. King, reveals that many of the suffrage publications, including Lydia Becker’s The Women’s Suffrage Journal, were published only on a commission basis.

Under this arrangement, the author or the society undertook all the risk of publication, while the publishers merely provided the service of printing, binding and distribution, for which they gave the book their imprint, charged a fee and took a percentage of sales. Publishers’ ledgers, where they have survived, provide an interesting keyhole through which to view the suffrage campaign. Lists of payments make it possible to identify an author who published anonymously, the print order for a book, journal or pamphlet can give us an idea of the ambition of the author or society; and the number of pulped gives a reason why so many of the items are now extremely scarce – and expensive.

The suffrage campaign appeared to have made such considerable progress in its first years that Mill, a canny businessman as well as philosopher, felt the time was ripe to publish the work that he had first drafted in the early 1860s on ‘the woman question’. As he wrote in a letter to The Times on 9 April 1869: ‘It is not specially on the Suffrage question, but on all the questions relating to women’s domestic subordination and social disabilities, all of which it discusses more fully than has been done hitherto. I think it will be useful, and all the more, it is sure to be bitterly attacked’. Mill knew full well the publicity value of controversy.

John Stuart Mill remained a hero to the more constitutionally-minded elements in the suffrage campaign

The Subjection of Women was published by Longmans in May 1869, went into a second edition in the same year, and has remained ever since a central text of the women’s movement.

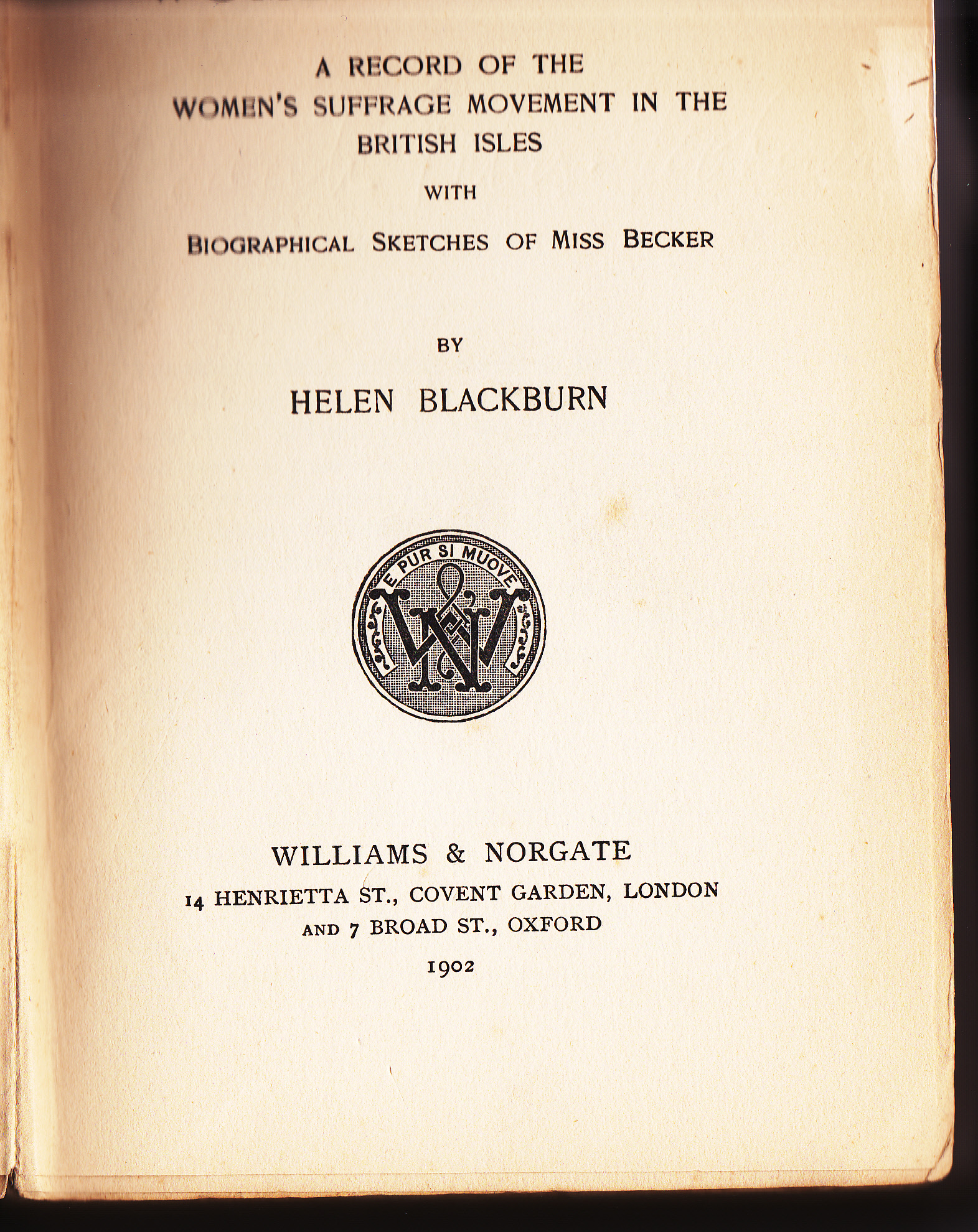

It took until 1902 for the first history of the campaign to appear. Women’s Suffrage: a record of the women’s suffrage movement in the British Isles with biographical sketches of Miss Becker was painstakingly compiled by Helen Blackburn, who had for many years worked as secretary of the Central Committee for Women’s Suffrage.

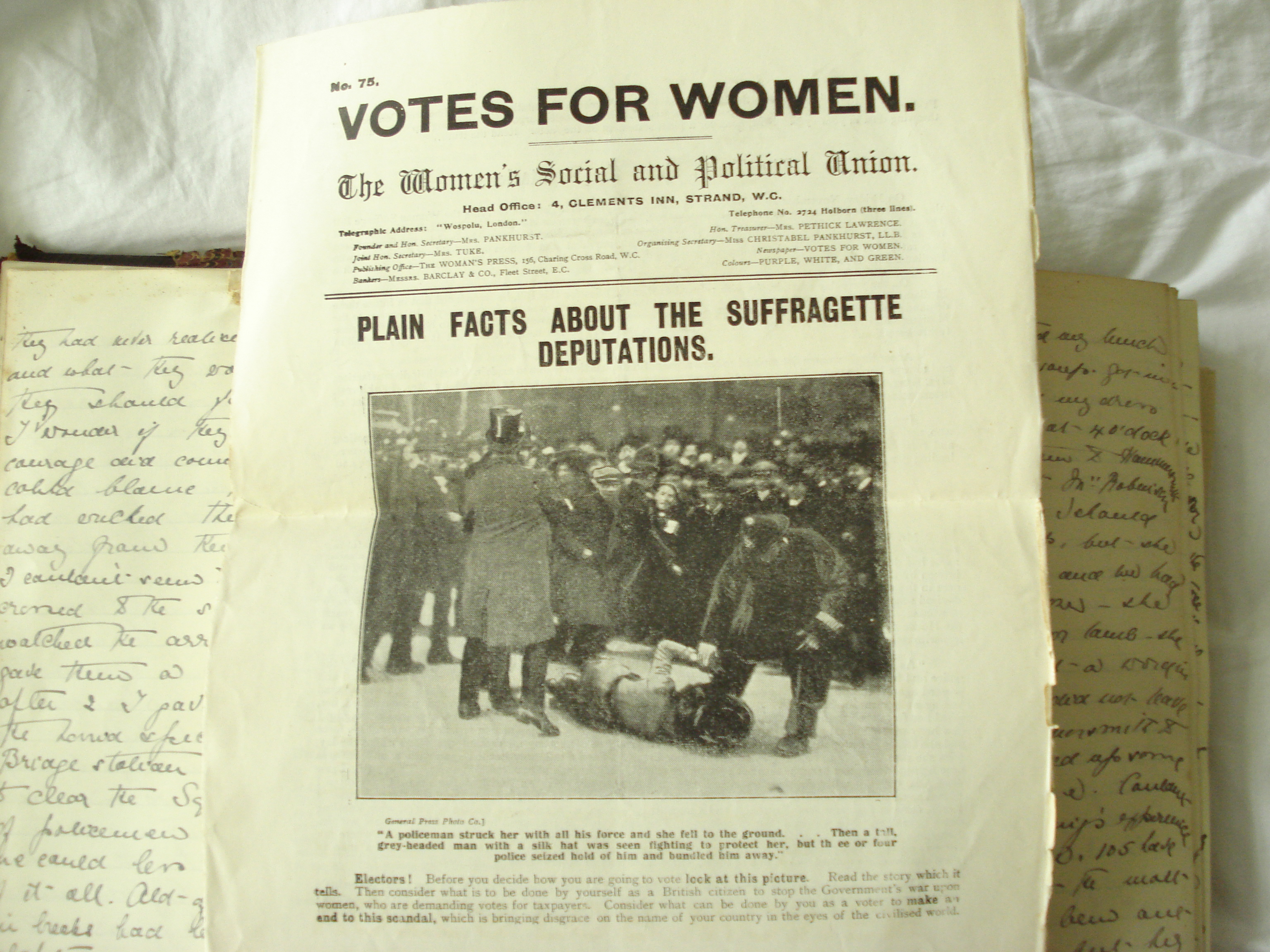

The new force that emerged in 1903, Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, did not delay so long before giving itself a distinctive history. A series of articles written by Sylvia Pankhurst, daughter of Emmeline, as The History of the Suffrage Movement, appeared in the WSPU’s new paper, Votes for Women, starting in the first issue in October 1907 and concluding in September 1909.

This history was, naturally, shaped to emphasise the Pankhursts’ centrality to the movement. Bibliophiles might like to note that the book that emerged from the articles, The Suffragette: the history of the women’s militant movement, was first published in America in 1911 by Sturgis & Walton and sheets where only then shipped back to Britain, where it was subsequently published by Gay & Hancock.

This history was, naturally, shaped to emphasise the Pankhursts’ centrality to the movement. Bibliophiles might like to note that the book that emerged from the articles, The Suffragette: the history of the women’s militant movement, was first published in America in 1911 by Sturgis & Walton and sheets where only then shipped back to Britain, where it was subsequently published by Gay & Hancock.

The publication in 1912 of Women’s Suffrage: a short history of a great movement (TC & EC Jack), written by Millicent Fawcett, did something to redress the balance. She had been involved with the campaign since its earliest days and since 1907 had been leader of those who described themselves as ‘law-abiding’ in contradistinction to the militants.

Agnes Metcalfe’s Woman’s Effort: a chronicle of British Women’s Fifty Years Struggle for Citizenship (1865-1914), published in 1917, gives a detailed overview of the campaign, concentrating on the efforts of the militants.

Agnes Metcalfe’s Woman’s Effort: a chronicle of British Women’s Fifty Years Struggle for Citizenship (1865-1914), published in 1917, gives a detailed overview of the campaign, concentrating on the efforts of the militants.

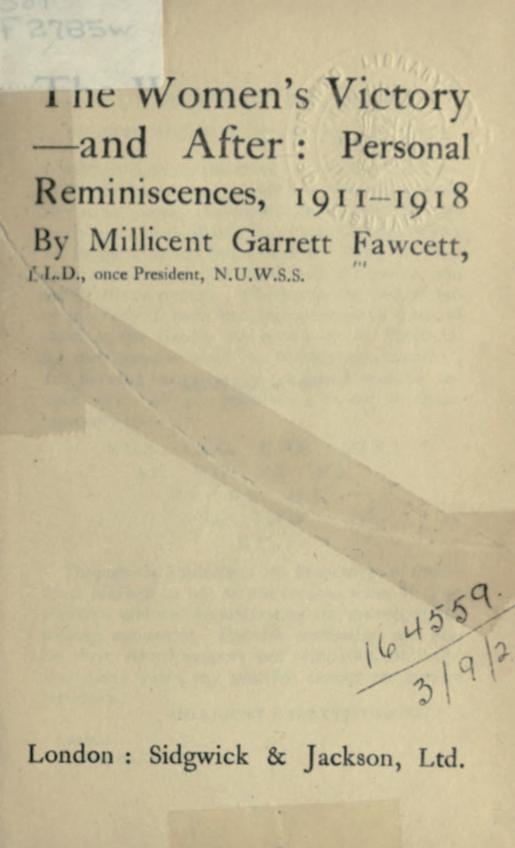

In 1920 Mrs Fawcett completed her history of the suffrage campaign, begun in A Short History, with another pithy summary of events that had led to the passing of the Representation of the People Act, 1918, granting the vote to women over the age of 30.

All these books were bought (as ownership inscriptions found in them testify) by sympathisers to the cause, were part of the stock of the small lending libraries run by many of the local suffrage societies and also found their way into the public library systems and even into prison libraries. While imprisoned, suffragettes were able to read lives, such as those of Joan of Arc and Garibaldi, that they considered (by analogy) relevant to their cause – the cult of the ‘hero’ clearly appealed to those conscious of their role in history.

Alongside the polemics, the women’s suffrage campaign also provided a rich seam mined by writers of fiction. John Francis Maguire, MP for Cork and an active supporter of the woman’s cause, was the first, publishing in 1871, a year before his death, a three-decker, The Next Generation (Hurst & Blackett). The action was set in 1891, by which time the ‘Rights of Woman’ movement..was a wonderful success [and had] long since been accepted with satisfaction almost universal’. Eighty-nine women MPs sat in parliament and Mrs Bates was chancellor of the exchequer.

The following year, ‘Arthur Sketchley’ in Mrs Brown on Women’s Rights (George Routledge) worked what Maguire had correctly identified as a ‘fruitful theme’, and demonstrated that his comic heroine, Martha Brown, had already got the measure of ‘women’s sufferages’. Mrs Brown surveys her first suffrage meeting: ‘Why, surely no Members of Parlyment aint a-coming to sich a ‘ole as this; for I’d ‘eard Miss Snapley a-braggin’ as Professor Fairplay were a-goin’ to take up the question in the chair, along with a old lady in the name of Mill, and a good many more as all ‘oped to be in Parlyment afore they died.’

The subject also, of course, lent itself to melodrama as well as to comedy. Emily Spender published in 1871 a novel, Restored (Hurst & Blackett, 1871) dedicated to the leader of the Bath society for women’s suffrage, of which she herself was an active member. In the novel a wicked husband, repossessing his young wife, declaims ‘If you had read your Bible a bit more, and John Stuart Mill, a little less, you would have been a better woman, Frederica.’ [Incidentally Emily Spender, the great-aunt of Sir Stephen Spender, spent her later years in Italyand was the model for E.M. Forster’s ‘Miss Lavish’ in Room with a View.]

Throughout the 19th century, a stream of novels used support for, or antipathy to, the suffrage cause as a shorthand by which to delineate characters or to put plot machinery into gear. An indication that the campaign was losing its momentum at the end of the century may be surmised from the fact that between 1900 and 1906 no ‘suffrage’ novels were published.

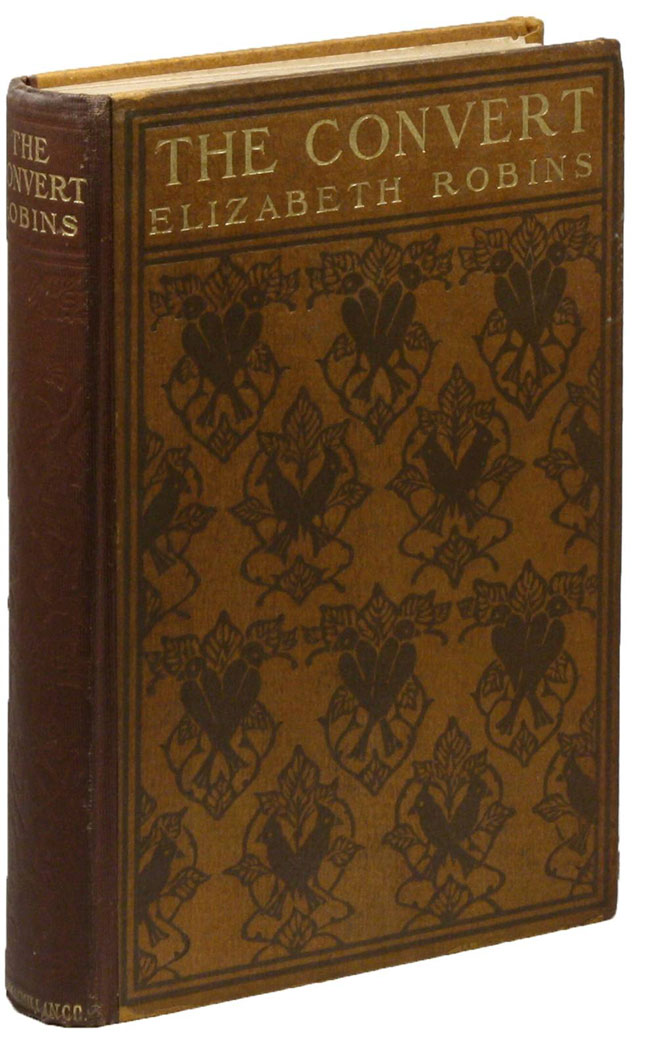

Robins, The Convert. Photo courtesy of Lorne Bair (click here to find a 1st US ed for sale)

However, in 1907, the year after the WSPU took its campaign to London, three novels appeared. The most famous of these is The Convert (Methuen) written by Elizabeth Robins, who was a keen supporter of the WSPU and based her scenes and personalities on activities of which she had been an eyewitness. Describing a suffrage rally in Trafalgar Square she drummed home the argument for the existence of the WSPU:

‘You’re in too big a hurry’, someone shouted, ‘All the Liberals want is a little time.’

‘Time! You seem not to know that the first petition in favour of giving us the Franchise was signed in 1866…We must try some other way. How did you working men get the suffrage?, we asked ourselves. Well, we turned to the records and we say. We don’t want to follow such a violent example. We would much rather not – but if that’s the only way we can make the country see we’re in earnest – we are prepared to show them.’

The Convert was in fact Elizabeth Robins’ novelisation of her play Votes for Women!, written during the autumn of 1906 and first staged at the Royal Court Theatre in April 1907. For Kate Parry Frye’s description of a visit to see the play on 16 April 1907 click here.

Elizabeth Robins, as author of ‘Votes for Women!’, featured on a card in ‘The Game of the Suffragette’

In the years that followed, the real-life activities of the suffragettes were reflected by the derring-do of their fictional equivalents in a steady stream of novels. Novelists could now take their middle-class readers into places they might not previously have sought to enter – even the prison cell – and were given legitimate reason to describe the indignities that might be wrought on women’s bodies, whether through the horrors of force-feeding or at the hands of policemen in battle outside the House of Commons. A hero of one such tale (A. Mollwo, A Fair Suffragette) is racked by ‘the picture of [a] fragile, slender little body at the mercy of this yelling, excited crowd, torn first one way, then another, insulted by angry policemen, knocked under the feet of horses.’

All in all, the wide range of ‘suffrage’ literature published during the course of the campaign – histories, tracts, speeches, leaflets and novels – offers historians and collectors a fascinating lens through which to view not only the political battle in all its complication, but also the changing perception of the position of women that in the end was so necessary to the winning the vote.

elizabeth Robins, harriet taylor, john francis maguire, john stuart mill, lydia becker, Millicent Fawcett, sylvia pankhurst

Suffrage Stories/Suffrage Collecting: WSPU Illuminated Address

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage, Suffrage Stories on April 30, 2014

Illuminated addresses such as this were first presented to WSPU prisoners on their release from Holloway in September 1908.

The addresses, signed by Emmeline Pankhurst, were designed by Sylvia Pankhurst and incorporate the purple, white and green colours that the WSPU had adopted three months earlier, in June 1908. The ‘angel of freedom’ device was one that Sylvia was to use on other WSPU artefacts – a neat piece of WSPU ‘branding’.

As ever, the suffrage collector needs to be on guard against modern reproductions that pass as the original. As a dealer I was once offered what appeared to be the address presented to suffragette Clara Codd. However, always rather suspicious, my research quickly revealed it to be a copy sold, entirely legitimately, by Bath-in-Time (the gallery of Bath Central Library). I was told that the unfortunate person offering the address to me had bought it as the real thing from a (presumably) rather unscrupulous source. Caveat Emptor.

holloway, suffrage collecting, sylvia pankhurst, wspu colours, wspu prisoners

Recent Posts

- Suffrage Stories: The Mystery of Nurse Pine’s Medal – Solved

- Mariana Starke and the Demon Duke: your opinion requested

- The Garretts And Their Circle: A Talk For International Women’s Day

- Books and Ephemera By and About Women: Catalogue 211

- Mariana Starke: ‘A Tissue of Coincidences’: Lady Mary De Crespigny And Hortense De Crespigny

Archives

- Join 2,785 other subscribers

All My Books

- Art and Suffrage: a biographical dictionary of suffrage artists

- Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye's Suffrage Diary

- Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle

- Kate Parry Frye: the long life of an Edwardian actress and suffragette – ebook available on iTunes

- Kate Parry Frye: the long life of an Edwardian actress and suffragette – ebook available on Amazon

- Millicent Garrett Fawcett: Selected Writings, co-edited with Melissa Terras

- The Women's Suffrage Movement: a reference guide

- The Women's Suffrage Movement: a regional survey

Articles

- 'Hunger Striking for the Vote'

- 'Women do not count, neither shall they be counted': Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the 1911 Census (co-authored with Jill Liddington). History Workshop Journal

- BBC History: Women: From Abolition to the Vote

- Emily Wilding Davison: Centennial Celebrations. Women's History Review

- Introduction to 'Bewildering Cares' by Winifred Peck

- Introduction to six novels by Elizabeth Fair

- Introduction to three novels by Rachel Ferguson

- Police, Prisons and Prisoners: the view from the Home Office. Women's History Review

- The Bloomsbury Project: A Woman Professional in Bloomsbury: Fanny Wilkinson, Landscape Gardener

Audio/Audio Visual

- 'Collecting The Suffragettes': A Fully-Illustrated Video Talk

- 'Collecting The Suffragettes': A Fully-Illustrated Video Talk

- 'Furrowed Middle-Brow Fiction'

- 'Suffragette': the making of the film. Q & A discussion hosted by the Women's Library@LSE

- BBC Radio 3: Kitty Marion: Singer, Suffragette, Firestarter

- BBC Radio 4 1913: The Year Before: The Women's Rebellion

- BBC Radio 4 Deeds Not Words: Emily Wilding Davison

- BBC Radio 4 Woman's Hour: The Garrett Andersons: Pioneering Mother And Daughter

- BBC Radio 4 Woman's Hour: Who Won the Vote for Women – the Suffragists or the Suffragettes?

- BBC Radio 4: Archive on Four: The Lost World of the Suffragettes

- BBC Radio 4: Great Lives: Millicent Fawcett

- BBC Radio 4: Millicent Fawcett, Votes for Women and British Liberalism

- BBC Radio 4: Things We Forgot To Remember: Suffragettes

- BBC Radio 4: Votes For Victorian Women

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour Suffragette Mary Richardson Who Slashed the Rokeby Venus

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour Suffragette Special 26 July 2013

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour: Emily Wilding Davison and the 1911 census boycott

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour: Suffragettes and Tea Rooms (starts c 27 min in)

- BBC Two 'Ascent of Women'

- BBC World Service Lost World of the Suffragettes

- Channel 4 TV: Clare Balding's Secrets of a Suffragette

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Millicent Fawcett

- Endless Endeavours: from the 1866 women's suffrage petition to the Fawcett Society: The Women's Library@LSE Podcast

- Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle.

- Fanny Wilkinson: A Talk

- ITV: The Great War The People's Story Episode 2 (including Kate Parry Frye and her diary)

- No Vote No Census. National Archives talk on the suffragette boycott of the 1911 census

- Parliamentary Radio: Interview in the House of Commons about Emily Davison on 4 June 2013

- The Royal Society of Medicine: Talk on 'Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her Hospital'

- UK Parliament Videoed Talk 'Vanishing for the Vote', together with Dr Jill Liddington and Prof Pat Thane

- UK Parliament: Videoed talk in the House of Commons: Campaigning for the Vote: from MP's Daughter to Suffrage Organiser – the diary of Kate Parry Frye

Guest Blogs

- British Library Untold Lives: Emily Wilding Davison: Perpetuating the Memory

- Feminist & Women's Studies Association Blog: Kate Frye: A Feminist Foot Soldier

- History of Government Blog: No 10 Guest Historian Series: We Wanted To Wake Him Up: Lloyd George And Suffragette Militancy

- History Workshop Online: Campaigning for The Vote: Kate Parry Frye's Suffrage Diary

- OUP Blog: Why Is Emily Wilding Davison Remembered As The First Suffragette Martyr?

View Books for Sale