Archive for category Walks

WALKS: What Would Bring Campaigning Women to Buckingham Street, Strand?

Posted by womanandhersphere in Walks on August 15, 2013

Ever since the decision was made for the Women’s Library to move to LSE (now open as the Women’s Library @ LSE) I have been writing posts that draw attention to the many locations associated with the women’s movement in the area around Aldwych and the Strand. My hope is that researchers in the Women’s Library, when taking a break from their labours, will welcome some information that will allow them to see the surrounding area with fresh eyes. Or even, as in the case of Buckingham Street, draw them to an area they may never have thought of visiting.

Buckingham Street, Strand, by John Edmund Niemann, 1854. From the Museum of London Collection, courtesy of the Public Catalogue foundation

Buckingham Street, Strand, by John Edmund Niemann, 1854. From the Museum of London Collection, courtesy of the Public Catalogue foundationBuckingham Street runs south from the Strand, parallel with Villiers Street, close to Charing Cross Station. In this picture Niemann positions us with our backs to the Strand, viewing the length of the street down towards the 17th-century Watergate which, before the building of the Embankment, marked the northern bank of the Thames. In the distance, looming over the Watergate, we can see the towers of Brunel’s Hungerford Suspension bridge, demolished in 1863. This view had, therefore, changed by the beginning of the 20th century, but from it we can glean an idea of the busy-ness of the narrow street,. There is probably less traffic now – at the moment, as London perpetually renews itself, this consists mainly of builders’ trucks – but the street still ends at the Watergate, by the side of which steps lead down into the Embankment Gardens.

The Survey of London, published in 1937, gives a thorough building history of the street and today’s London guides – such as this one– mention that Pepys lived at number 12 and Dickens at number 15 (his house now bombed and replaced), but campaigning women, too, have a claim to the street’s history.

18 Buckingham Street, Strand, first home of the WFL, 1907-08

18 Buckingham Street, Strand, first home of the WFL, 1907-08It was here – at no 18 (at the quieter, river-end of Buckingham Street) that in the autumn of 1907, after the dramatic break with Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, the newly formed Women’s Freedom League opened its office. This was always probably only intended as a temporary solution – the WFL moved to larger premises in nearby Robert Street the following year. I have always wondered whether billiards was not the reason for alighting on no 18 – which at this time also housed the office of the Billiards Association. Teresa Billington-Greig, one of those leading the break with the WSPU, had that year married Frederick Greig, a manufacturer of billiard tables – so, perhaps, when it was clear that they would have to depart Clement’s Inn in a hurry, it was through him that the rebels heard of an office for rent. I’ve not, however, been able to find any proof for this – doubtlessly wild – supposition. Perhaps, rather, the Strand Liberal and Radical Association, also tenants of number 18, effected the introduction to Buckingham Street.

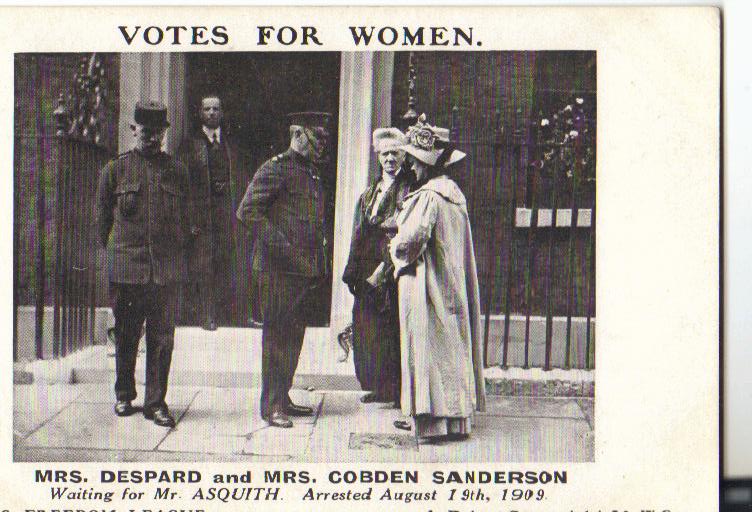

The WFL lost no time in advertising their existence – issuing several photographic cards during the few months they were operating from number 18.

WSL card published from 18 Buckingham Street

WSL card published from 18 Buckingham Street 13 Buckingham Street, Strand, office of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement

13 Buckingham Street, Strand, office of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s EnfranchisementOn the other side of the street the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement was based at number 13. The MPU had been founded at a meeting held at the Eustace Miles Restaurant (just the other side of the Strand) in 1910. One of the founders – and the hon. organising secretary of the MPU – was Victor Duval. The premises were also, I think, the offices of his family firm, Duval & Co. Victor’s mother, Emily Duval, had been one of those who transferred allegiance from the WSPU to the WFL and would doubtless have been a regular visitor to number 18.

19 Buckingham Street, Strand

19 Buckingham Street, StrandBack on the eastern side of the street, number 19, now under scaffolding as it is remodelled as ‘luxury apartments’, is a considerably larger building than its neighbour, no 18. Among its many tenants was the Emerson Club which in 1908 was described as a ‘Ladies’ Club’ but from 1911 welcomed both men and women members. This was still rather unusual. The Emerson remained at this address until 1925 and numbered among its members the WFL activists Elizabeth Knight, Amy Hicks and Alison Neilans, as well as Mrs Pankhurst’s brother, Walter, and Margaret Bondfield, the future Labour cabinet minister. Sarah Bennet, the WFL’s treasurer, was one of the Emerson’s early shareholders.

By 1908 number 19 also housed the office of the architect Basil Champneys, while Thackeray Turner and Eustace Balfour (the latter the husband of the suffragist Lady Frances Balfour) had their architectural practice next door at number 20. All three architects brought to fruition – mainly in Queen-Anne style red brick – the dreams of campaigning women. Champneys was the long-time architect of Newnham College and In the 1890s Turner and Balfour designed the York Street Ladies’ Residential Chambers – one of Agnes Garrett’s projects (for which see much more in Crawford, Enterprising Women). Thackeray Turner was also secretary to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, at this time also based at number 20. The architects were working out of the type of late-17th/early-18th-century houses so much admired by Agnes and Rhoda Garrett in House Decoration.

Opposite, at number 12, were the offices of the Incorporated Society of Trained Masseuses, the premises of the Midwives’ Institute and Trained Nurses’ Club and the Association of Clerks and Secretaries.

So, a 100 years ago, many different types of women would have had many reasons to make their way down Buckingham Street, stopping off at any one of these addresses. Some might, of course, have carried on down the steps at the end of the street and into the Victoria Embankment Gardens – where two major heroes of the suffrage movement are commemorated.

The WFL, based on the south side of the Strand, was very well placed to honour, as they did every year, their particular hero, John Stuart Mill, whose statue is one of several in the Embankment Gardens. (Incidentally you will note from the caption to this card that the WFL had moved into the new Robert Street office by May 1908.) Well into the 1920s women laid tribute before the statue – one 1927 photograph in the Women’s Library collection shows Millicent Fawcett present on such an occasion.

Henry Fawcett’s memorial, erected 1886

Henry Fawcett’s memorial, erected 1886And it is Millicent’s husband, Henry Fawcett, who is the other hero memorialised in the Embankment Gardens. The sculptor of the bronze bust was a woman – Mary Grant, the fountain’s designer was Basil Champneys and the whole was funded, as the inscription testifies, by Henry Fawcett’s ‘grateful countrywomen’.

For more information about the people and societies mentioned see Crawford: The Women’s Suffrage Movement: a reference guide.

And do consult the Women’s Library @ LSE online catalogue for details of primary source material.

WALKS: The Women’s Library @ LSE Now Open

Posted by womanandhersphere in Walks on August 1, 2013

Today, 1 August 2013, is a red-letter day for women’s history researchers – for once again they have access to the magnificent Women’s Library archive and museum collections – now open at The Women’s Library @LSE. With research having, perforce, been put on hold for the last few months there was doubtless an impatient queue outside the doors this morning.

Today, 1 August 2013, is a red-letter day for women’s history researchers – for once again they have access to the magnificent Women’s Library archive and museum collections – now open at The Women’s Library @LSE. With research having, perforce, been put on hold for the last few months there was doubtless an impatient queue outside the doors this morning.

As a long-time user of the Women’s Library – with fond memories of the Fawcett Library and its Tardis-like basement – I was delighted to find an interview with David Doughan – the Fawcett’s dedicated custodian – on the LSE Blog. It is so important that women historians remember their own historiography.

I must say that, when hearing that LSE, (as, of course, do so many other institutions) likes to reward those who give very large donations by attaching their name to a room or building – I regretted even more that Millicent Fawcett’s name has been detached from the Library inaugurated in her memory. The Women’s Library@LSE has a very bright future, but we mustn’t forget the past on which it is built.

When – or if – those patient researchers now able to access the Women’s Library@LSE are able to tear themselves away from their papers, I have, over the last few months, created a series of posts on buildings in the area around LSE that relate to the Woman’s Cause. You will find links to them all under the Walks tab at the top of this blog. I thought the information contained in these posts might bring the area to life while legs are stretched and fresh (?) air breathed during strolls around the Aldwych area.