Posts Tagged Women’s freedom League

Collecting Suffrage: Mrs Amy Sanderson, Scottish Speaker For The Women’s Freedom League

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on September 18, 2020

Mrs Amy Sanderson, born in Bellshill, Lanarkshire, joined the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1906 and took part in the deputation in February 1907 from the first Women’s Parliament in Caxton Hall to the House of Commons, was arrested and served a Holloway prison term.

She actively campaigned in Scotland for the WSPU before, in October 1907, joining those who broke away to form the Women’s Freedom League. becoming for 3 years a member of the WFL executive committee. In 1908 she served another prison term.

She was a very popular speaker for the WFL and, in 1912, for the ‘Women’s March’ from Edinburgh to London.

In this photograph she is wearing her ‘Holloway brooch’, given by the WFL in recognition of her imprisonment.

The card, issued by the WFL no later than November 1909, after which date the Scottish Glasgow headquarters moved from Gordon Street to Sauchiehall Street, is in fine, unposted condition. £130 + VAT in UK and the EU.

Email me if interested in buying. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

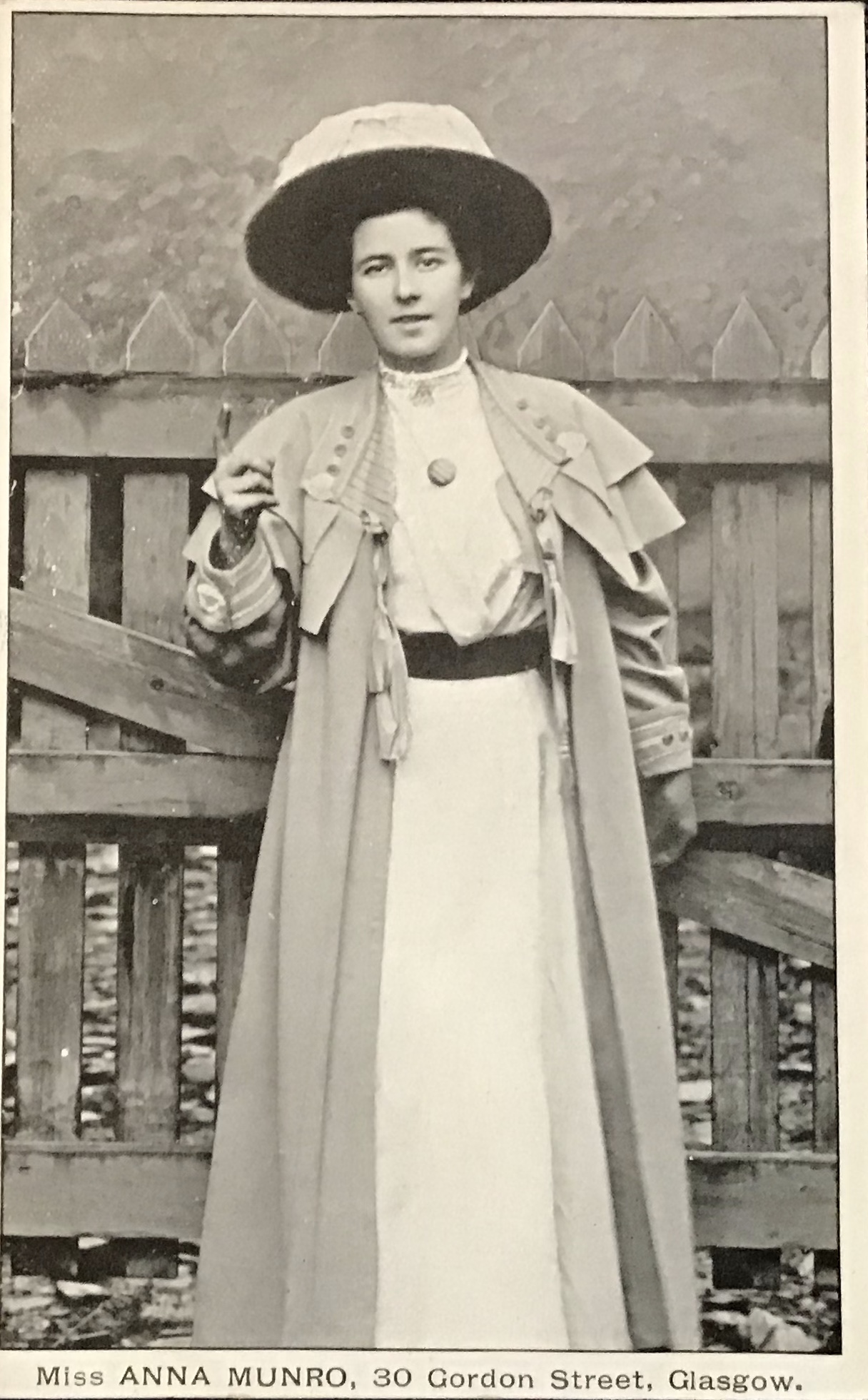

Collecting Suffrage: Anna Munro, Organizer For The Scottish Council Of The Women’s Freedom League

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on September 17, 2020

Full-length portrait photograph of Anna Munro (1881-1962) Scottish organiser for the Women’s Freedom League. The address is that of the WFL Scottish headquarters.

Anna Munro had joined the WSPU in 1906, becoming its organizer in Dunfermline. The following year she followed Teresa Billington-Greig into the WFL, becoming her private secretary. She was imprisoned in Holloway in early 1908 before being appointed organizing secretary of the Scottish Council of the WFL.

After the First World War Anna Munro (now Mrs Ashman) became a magistrate in England and was later president of the WFL in which she remained active until its disbanding in 1961.

Photographic postcards of Scottish suffragettes are relatively uncommon. This one is in fine, unposted condition. £130 + VAT in UK and EU. Email me if interested in buying. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

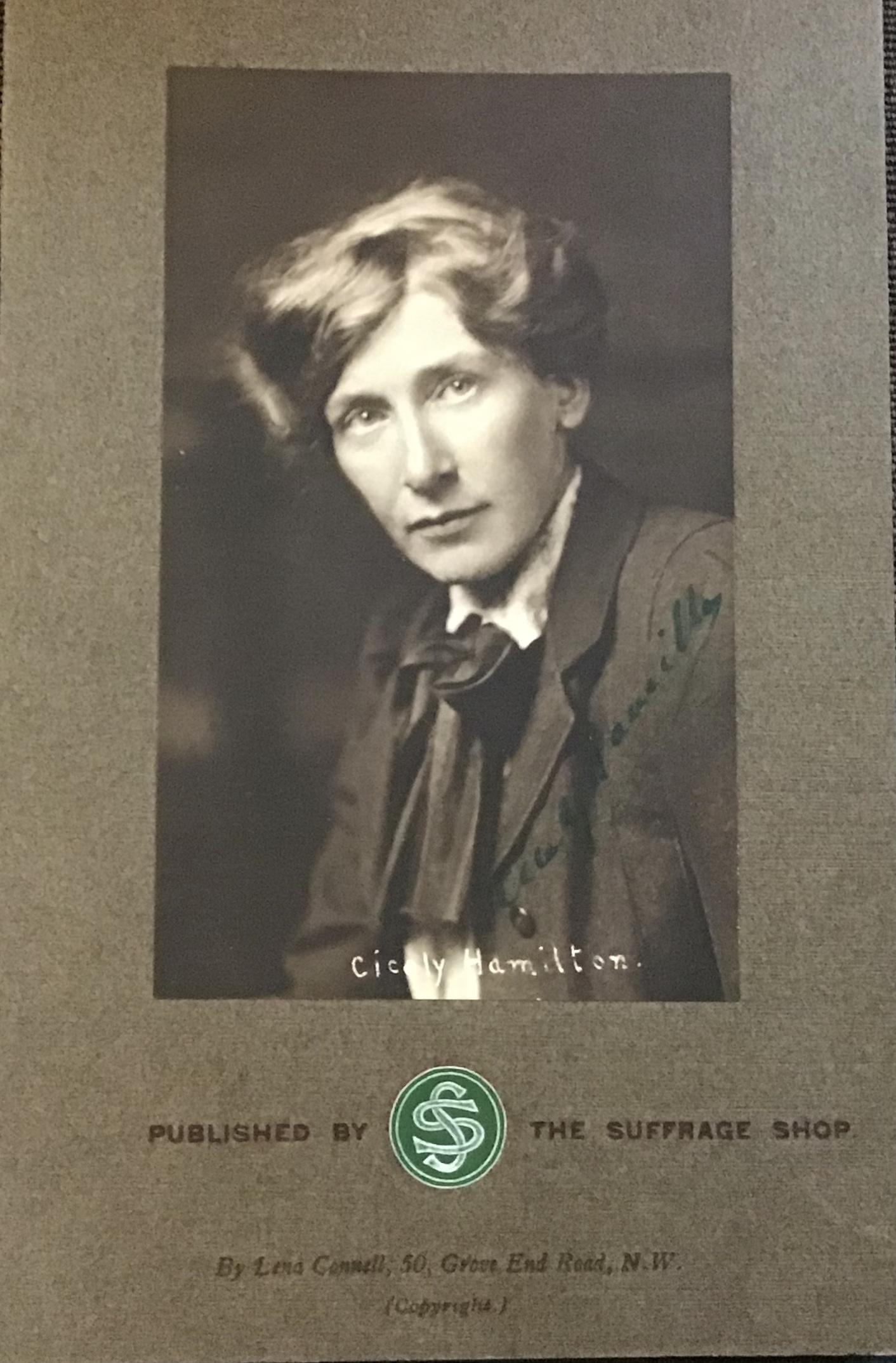

Collecting Suffrage: Photograph Of Cicely Hamilton By Lena Connell For The Suffrage Shop

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on September 14, 2020

Photograph of a luminous Cicely Hamilton, writer, actor and suffrage activist, taken by Lena Connell, the renowned photographer.

The close-up photograph is mounted on stiff card, which carries the logo of The Suffrage Shop, 15 Adam Street, Strand, London. Hamilton was closely associated with the Suffrage Shop, which in 1910 published her Pageant of Great Women.

The photograph was probably taken c 1910/1911. Hamilton’s name has been scratched on the emulsion, presumably by the photographer, and it is signed by Cicely Hamilton. SOLD

If interested in buying, do email me. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

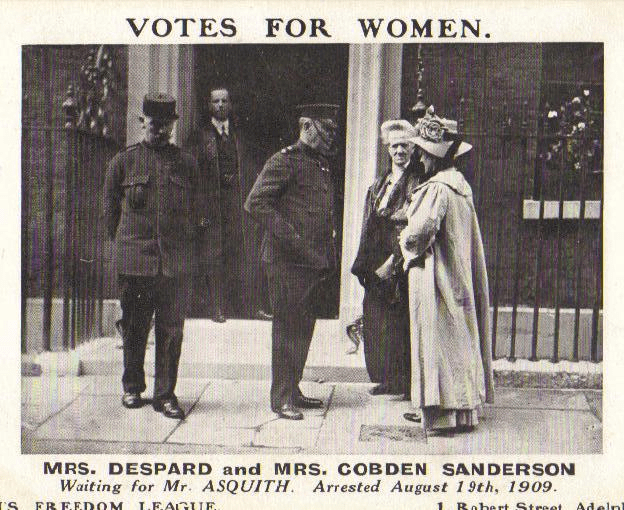

Collecting Suffrage: Mrs Charlotte Despard Photographed by Christina Broom

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on September 9, 2020

A lovely photograph of Mrs Charlotte Despard, leader of the Women’s Freedom League. It was taken on a rooftop, possibly at the time of the WFL’s White, Gold and Green Fair in 1909.

The photographer and publisher of the resultant postcard was Mrs Albert Broom (Christina Broom), who photographed several groups of those participating in that WFL Fair.

In fine, unposted, condition. A scarce image. Sold

Email me if interested in buying. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

WALKS: What Would Bring Campaigning Women to Buckingham Street, Strand?

Posted by womanandhersphere in Walks on August 15, 2013

Ever since the decision was made for the Women’s Library to move to LSE (now open as the Women’s Library @ LSE) I have been writing posts that draw attention to the many locations associated with the women’s movement in the area around Aldwych and the Strand. My hope is that researchers in the Women’s Library, when taking a break from their labours, will welcome some information that will allow them to see the surrounding area with fresh eyes. Or even, as in the case of Buckingham Street, draw them to an area they may never have thought of visiting.

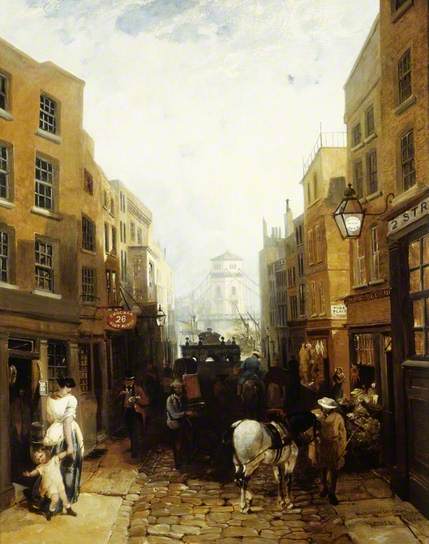

Buckingham Street, Strand, by John Edmund Niemann, 1854. From the Museum of London Collection, courtesy of the Public Catalogue foundation

Buckingham Street, Strand, by John Edmund Niemann, 1854. From the Museum of London Collection, courtesy of the Public Catalogue foundationBuckingham Street runs south from the Strand, parallel with Villiers Street, close to Charing Cross Station. In this picture Niemann positions us with our backs to the Strand, viewing the length of the street down towards the 17th-century Watergate which, before the building of the Embankment, marked the northern bank of the Thames. In the distance, looming over the Watergate, we can see the towers of Brunel’s Hungerford Suspension bridge, demolished in 1863. This view had, therefore, changed by the beginning of the 20th century, but from it we can glean an idea of the busy-ness of the narrow street,. There is probably less traffic now – at the moment, as London perpetually renews itself, this consists mainly of builders’ trucks – but the street still ends at the Watergate, by the side of which steps lead down into the Embankment Gardens.

The Survey of London, published in 1937, gives a thorough building history of the street and today’s London guides – such as this one– mention that Pepys lived at number 12 and Dickens at number 15 (his house now bombed and replaced), but campaigning women, too, have a claim to the street’s history.

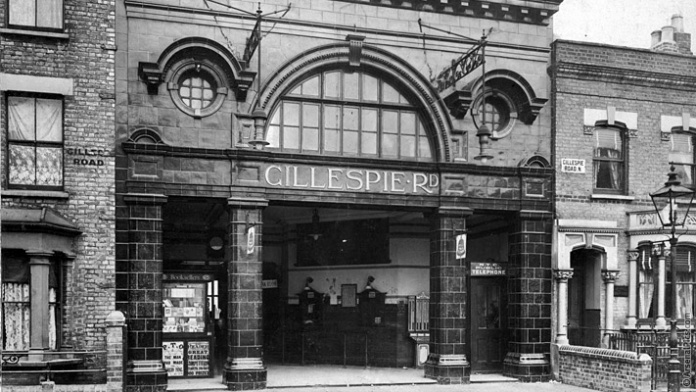

18 Buckingham Street, Strand, first home of the WFL, 1907-08

18 Buckingham Street, Strand, first home of the WFL, 1907-08It was here – at no 18 (at the quieter, river-end of Buckingham Street) that in the autumn of 1907, after the dramatic break with Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, the newly formed Women’s Freedom League opened its office. This was always probably only intended as a temporary solution – the WFL moved to larger premises in nearby Robert Street the following year. I have always wondered whether billiards was not the reason for alighting on no 18 – which at this time also housed the office of the Billiards Association. Teresa Billington-Greig, one of those leading the break with the WSPU, had that year married Frederick Greig, a manufacturer of billiard tables – so, perhaps, when it was clear that they would have to depart Clement’s Inn in a hurry, it was through him that the rebels heard of an office for rent. I’ve not, however, been able to find any proof for this – doubtlessly wild – supposition. Perhaps, rather, the Strand Liberal and Radical Association, also tenants of number 18, effected the introduction to Buckingham Street.

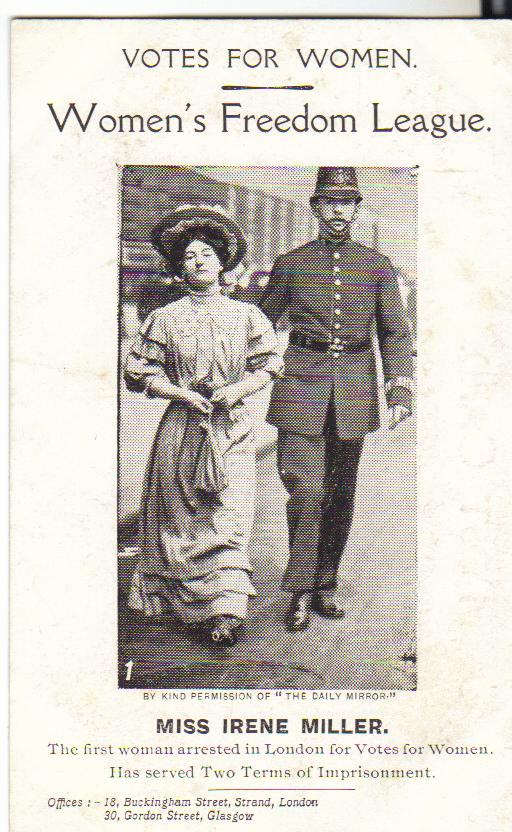

The WFL lost no time in advertising their existence – issuing several photographic cards during the few months they were operating from number 18.

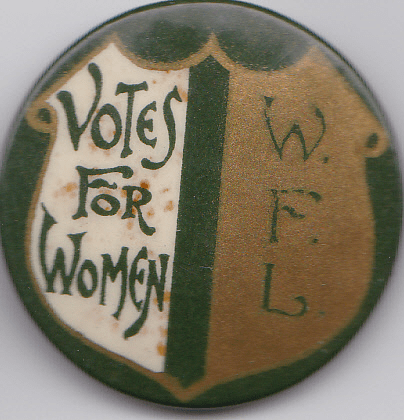

WSL card published from 18 Buckingham Street

WSL card published from 18 Buckingham Street 13 Buckingham Street, Strand, office of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement

13 Buckingham Street, Strand, office of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s EnfranchisementOn the other side of the street the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement was based at number 13. The MPU had been founded at a meeting held at the Eustace Miles Restaurant (just the other side of the Strand) in 1910. One of the founders – and the hon. organising secretary of the MPU – was Victor Duval. The premises were also, I think, the offices of his family firm, Duval & Co. Victor’s mother, Emily Duval, had been one of those who transferred allegiance from the WSPU to the WFL and would doubtless have been a regular visitor to number 18.

19 Buckingham Street, Strand

19 Buckingham Street, StrandBack on the eastern side of the street, number 19, now under scaffolding as it is remodelled as ‘luxury apartments’, is a considerably larger building than its neighbour, no 18. Among its many tenants was the Emerson Club which in 1908 was described as a ‘Ladies’ Club’ but from 1911 welcomed both men and women members. This was still rather unusual. The Emerson remained at this address until 1925 and numbered among its members the WFL activists Elizabeth Knight, Amy Hicks and Alison Neilans, as well as Mrs Pankhurst’s brother, Walter, and Margaret Bondfield, the future Labour cabinet minister. Sarah Bennet, the WFL’s treasurer, was one of the Emerson’s early shareholders.

By 1908 number 19 also housed the office of the architect Basil Champneys, while Thackeray Turner and Eustace Balfour (the latter the husband of the suffragist Lady Frances Balfour) had their architectural practice next door at number 20. All three architects brought to fruition – mainly in Queen-Anne style red brick – the dreams of campaigning women. Champneys was the long-time architect of Newnham College and In the 1890s Turner and Balfour designed the York Street Ladies’ Residential Chambers – one of Agnes Garrett’s projects (for which see much more in Crawford, Enterprising Women). Thackeray Turner was also secretary to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, at this time also based at number 20. The architects were working out of the type of late-17th/early-18th-century houses so much admired by Agnes and Rhoda Garrett in House Decoration.

Opposite, at number 12, were the offices of the Incorporated Society of Trained Masseuses, the premises of the Midwives’ Institute and Trained Nurses’ Club and the Association of Clerks and Secretaries.

So, a 100 years ago, many different types of women would have had many reasons to make their way down Buckingham Street, stopping off at any one of these addresses. Some might, of course, have carried on down the steps at the end of the street and into the Victoria Embankment Gardens – where two major heroes of the suffrage movement are commemorated.

The WFL, based on the south side of the Strand, was very well placed to honour, as they did every year, their particular hero, John Stuart Mill, whose statue is one of several in the Embankment Gardens. (Incidentally you will note from the caption to this card that the WFL had moved into the new Robert Street office by May 1908.) Well into the 1920s women laid tribute before the statue – one 1927 photograph in the Women’s Library collection shows Millicent Fawcett present on such an occasion.

Henry Fawcett’s memorial, erected 1886

Henry Fawcett’s memorial, erected 1886And it is Millicent’s husband, Henry Fawcett, who is the other hero memorialised in the Embankment Gardens. The sculptor of the bronze bust was a woman – Mary Grant, the fountain’s designer was Basil Champneys and the whole was funded, as the inscription testifies, by Henry Fawcett’s ‘grateful countrywomen’.

For more information about the people and societies mentioned see Crawford: The Women’s Suffrage Movement: a reference guide.

And do consult the Women’s Library @ LSE online catalogue for details of primary source material.

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: Palmist At The Women’s Freedom League Bazaar

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on December 10, 2012

By 1909 Kate Frye was keenly involved – as a volunteer – in the women’s suffrage campaign. Although she belonged to the constitutional London Society for Women’s Suffrage she was happy to give her services to other, more militant, suffrage societies – such as the Women’s Freedom League.

By 1909 Kate Frye was keenly involved – as a volunteer – in the women’s suffrage campaign. Although she belonged to the constitutional London Society for Women’s Suffrage she was happy to give her services to other, more militant, suffrage societies – such as the Women’s Freedom League.

Dramatis Personae for these entries

Marie Lawson (1881-1975) was a leading member of the WFL. An effective businesswoman, in 1909 she formed the Minerva Publishing Co. to produce the WFL’s weekly paper, The Vote.

May Whitty (1865-1948) and Ben Webster (1864-1947) were a well-established theatrical couple. Kate had toured with May Whitty in a production of J.M. Barrie’s Quality Street in 1903.

Ellen Terry (1847-1928) the leading Shakesperean actress of her age.

Edith Craig (1869-1947) theatre director, producer, costume designer, and a very active member of the Actresses’ Franchise League. She staged a number of spectacles for suffrage societies, working particularly closely with the Suffrage Atelier and the Women’s Freedom League. In January 1912 Kate appeared in Edith Craig’s production of The Coronation.

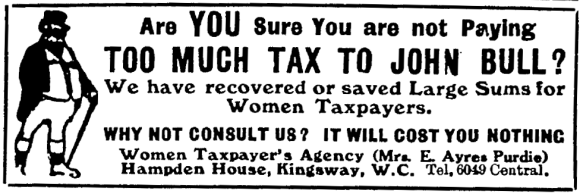

Lena Ashwell (1862-1957) actress, manager of the Kingsway Theatre, a vice-president of the Actresses’ Franchise League and a tax resister.

Thursday April 15th 1909 [The Plat, Bourne End]

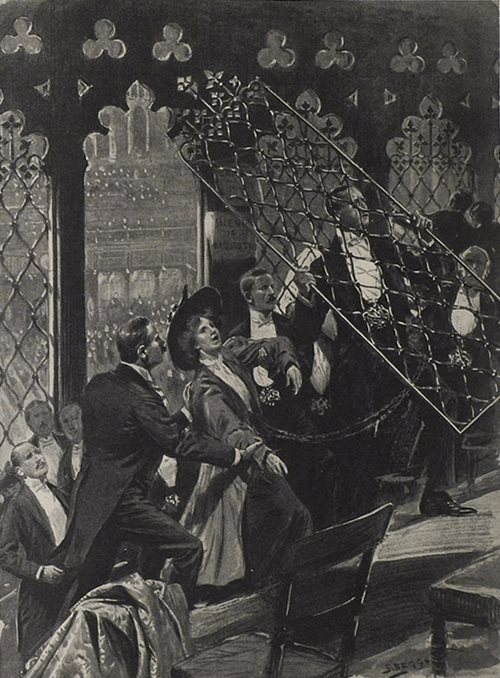

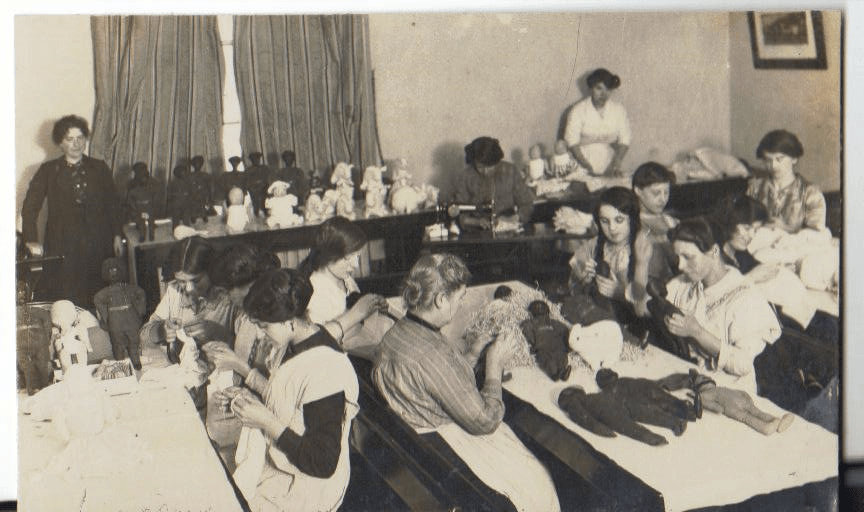

I went up to London at 9.50 all in my best. Went to Smiths to leave the books – then straight from Praed St to St James Park by train and to the Caxton Hall for the 1st day of the Women’s Freedom League Bazaar. Got there about 11.30 – everything in an uproar, of course. I had to find out who was in authority over me and where I was to go to do my Palmistry. I had to find a Miss Marie Lawson first and then was taken to a lady who had charge of my department and she arranged where I was to go. A most miserable place it seemed – in a gallery overlooking the refreshment room. I meant to have gone out to have a meal first – but it all took me so long running about getting an extra chair etc that I should have missed the opening. Then another Palmist hurried up – the real thing who donned a red robe. I was jealous. Madame Yenda.

We got on very well, however, and exchanged cards (I have had some printed) it was all about as funny as anything I have ever done and I have had some experiences.

Then I went back to the main room which was beginning to get thronged and stifling from the smell of flash- light photographs. I discovered Miss May Whitty and Mr Ben Webster and chatted to them while we waited for Miss Ellen Terry who was half an hour late. Miss Whitty was awfully nice and I quite enjoyed meeting her again. Ellen Terry looked glorious in 15th century costume and was very gay and larkish. Her daughter Edith Craig was there to look after and prompt her – and ‘mother’ her – what a mother to have had. I expect she had to pay for it. She is a sweet-looking woman with a most clever face – only a tiny shade of her Mother in it but Ellen Terry took the shine out of everyone – what a face to be sure. When she went round the stalls I went to the Balcony and for a little time Madame Yenda and I tried to work up there together but it was impossible. All my clients had to disturb her as they walked to and fro so at last I came out to find 3 more Palmists waiting and nowhere for them to work. One, a real professional, was very cross especially at the small fee being charged and I don’t think she could have been there long. Two other girls, looking real amateurs, were also there. So I sat a while at a table outside and told a few but it wasn’t very satisfactory and at 2 o’clock I went out for some lunch leaving the four others there. I went into a Lyons place in Victoria Street and then went back a little before 3 o’clock meaning to have a look round the Bazaar but I was pounced on to begin again and I was alone at it all the afternoon from 3 till 5.45 up in the gallery. I was left at it with sometimes just a few minutes in between but must have told 40 hands I should say. I did about 7 or 8 before 2 o’clock. We were only supposed to give 10 minutes at the outside but I could not quite limit myself and sometimes, when there wasn’t a rush, I had long talks with the people. It was very interesting and on the whole I think I was successful. Train to Praed St and to Smiths for the books and home by the 6.45.

Friday April 16th 1909 [The Plat, Bourne End]

I went straight to Caxton Hall by train from Praed St to St James’s Park – left some flowers at the flower stall. Mother had packed up some lovely bunches for me. Then I went up to the l[ondon] S[ociety] for W[omen’s] S[uffrage] office on business connected with the Demonstration – then back to the Caxton Hall for the opening of the Green White and Gold Fair on the second day. Miss Lena Ashwell was punctual 12 o’clock and she looked delicious and did it all so nicely. Madame Yenda was there but no other Palmists. My chatty friend, who greeted me rapturously, helped fix up the gallery a much nicer place – but clients did not come very early -they were all following Lena Ashwell – so I had 1/- from Madame Yenda myself. I think she was clever but, of course, I am rather a hard critic at it. She told me a great many things I know to be absolutely true and she gave me some good advice especially about morbid introspective thoughts and I think she is quite right. I do over worry. I am to beware of scandal which is all round me just now. She predicts a broken engagement, a rich alliance and always heaps of money. I should have immense artistic success in my profession if only I had more confidence in myself and if only I had some favourable influence (a sort of back patter, I take it) to help me but such an influence is far away. I shall never live a calm uneventful existence. I shall always spend so much of myself with and for others. I am rather glad of that. I was just beginning to tell her her hand but I wouldn’t let her pay as she told me she was very poor and I could see it when some clients came for us both and we both had to start our work.

I didn’t feel a bit inclined for work at first but got into it and had wonderful success. Kept on till 2 o’clock – went to the Army and Navy Stores then and had some fish for lunch – then back – saw the ‘Prison Cell’ for 5 and was very interested – then started work at 2.45 and never moved off my chair till 6.15. I did have an afternoon of it. Madame Yenda had gone and I was alone in my glory. I must have had quite another 40 people if not more and they were waiting in line to come in to me. I seem to delight some of the people and one or two said I quite made them believe in Palmistry. One old lady came back for another shill’oth [shilling’s worth] as I had been so good with her past and present she wanted her future. I must have been very clairvoyant as I told the people extraordinary things sometimes and they said I was ‘true’. Of course one or two I could not make much headway with but that must always be so.

Where I found I had missed my train I wanted to go on but my chatty friend was really awfully decent and would not hear of it. She said if I would tell one man who had been waiting ever so long that was all I must do and she would send the others away. There were about 18 waiting and she did – rather to my relief. I felt ‘done’

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

NOW, ALAS, OUT OF PRINT.

KATE FRYE’S DIARIES AND ASSOCIATED PAPERS ARE NOW HELD BY ROYAL HOLLOWA COLLEGE ARCHIVE

You can listen here to a talk I gave in the House of Commons – ‘Campaigning for the Vote: From MP’s Daughter to Suffrage Organiser: the diary of Kate Parry Frye’.

Copyright

Suffragette postcards: real photographic portrait

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on July 28, 2012

Here is an example of a real photographic postcard issued by a suffrage society – in this case by the Women’s Freedom League. Its subject is Mrs Lilian Hicks (1853-1924) who, with her daughter, Amy, was at that time of its publication a leading member of the WFL – as well as a supporter of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage and the Tax Resistance League. Both mother and daughter, by then members of the Women’s Social and Political Union, heeded the call to boycott the 1911 census.

Here is an example of a real photographic postcard issued by a suffrage society – in this case by the Women’s Freedom League. Its subject is Mrs Lilian Hicks (1853-1924) who, with her daughter, Amy, was at that time of its publication a leading member of the WFL – as well as a supporter of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage and the Tax Resistance League. Both mother and daughter, by then members of the Women’s Social and Political Union, heeded the call to boycott the 1911 census.

The Hicks’ association with a wide range of suffrage societies, of which I had written a few years earlier in their joint entry in my Women’s Suffrage Movement: a reference guide, was made manifest in the magnificent collection of badges and awards – including a hunger-strike medal – that many years ago I acquired from a woman to whom they had been indirectly bequeathed. They are now held in a private collection.

Lilian and Amy Hicks lived here, at 33 Downside Crescent, Hampstead. At the other end of the street was the home – probably the rather unhappy home – of Margaret Wynne Nevinson, a fellow member of the Women’s Freedom League. I realised that a bond of friendship existed between the two women when, all those years ago, I recognised – hanging on the wall of the sitting-room in the small cottage of the woman from whom I was buying the collection of Hicks’ memorabilia – a large painting by Margaret’s son, C.R. Nevinson. It was in the guise of ‘the mother of the Futurists’ that Margaret went when she attended a dinner given by the Women Writers’ Suffrage League at the Hotel Cecil on 29 June 1914. Unfortunately there is no record of the form of dress that this witty allusion took.

Lilian and Amy Hicks lived here, at 33 Downside Crescent, Hampstead. At the other end of the street was the home – probably the rather unhappy home – of Margaret Wynne Nevinson, a fellow member of the Women’s Freedom League. I realised that a bond of friendship existed between the two women when, all those years ago, I recognised – hanging on the wall of the sitting-room in the small cottage of the woman from whom I was buying the collection of Hicks’ memorabilia – a large painting by Margaret’s son, C.R. Nevinson. It was in the guise of ‘the mother of the Futurists’ that Margaret went when she attended a dinner given by the Women Writers’ Suffrage League at the Hotel Cecil on 29 June 1914. Unfortunately there is no record of the form of dress that this witty allusion took.

The photograph of Mrs Hicks on this official Women’s Freedom League postcard was taken by Lena Connell and probably issued around 1909/10.

Mrs Lilian Hicks was a member of the Women’s Freedom League