Posts Tagged new constitutional society for women’s suffrage

Kate Frye’s Diary: The Lead-Up To War: 20 July 1914

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's Diary on July 20, 2014

On 7 August 2014 ITV will publish an e-book, Kate Parry Frye: The Long Life of an Edwardian Actress and Suffragette. Based on her prodigious diary, this is my account of Kate Frye’s life and is a tie-in with the forthcoming ITV series ‘The Great War: The People’s Story’. For details of the TV series and its accompanying books see here.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

Kate was at this time 36 years old, living in a room at 49 Claverton Street in Pimlico and working in the Knightsbridge headquarters of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was now nine years since she had become engaged to (minor) actor John Collins. Her father died in March 1914 and her mother and sister, Agnes, now all but penniless, are living in rented rooms in Worthing. John has a room along Claverton Street, at number 11.

Monday 20th July 1914

Woke up at 6 and thought of John and then went to sleep again. Called at 8. Breakfast at 9 and then slept on until 10.30 when I realised I had not breakfasted – so got up and recooked the egg and dressed and went out at 2 o’clock. Had some lunch and did some shopping – in at 3.30 – had a rest and went to sleep again.

Tea at 6 – and then off to Peckham for the open-air meeting. Self in Chair and Mrs Kerr as speaker. We finished at 10.15. Home soon after 11. We did not have quite such a big crowd as usual. I was bitterly tired.

Well, life certainly does seem dreary for Kate without John.

As yet Kate, who was a keen reader of newspapers, has not commented on events in Europe or in Ireland- and nor does she mention details of the increasingly militant WSPU campaign. For instance, on 14 July an attempt was made to burn down Cocken House, owned by Lord Durham, on 15 July the Secretary for Scotland was attacked with a dog whip, on this very Monday suffragettes interrupted a service in Perth Cathedral protesting against forcible feeding of suffragettes in Perth Prison, and on 17 July a WSPU member had attacked Thomas Carlyle’s portrait in the National Portrait Gallery (see my post about the current NPG exhibition commemorating this here). It was against this background that the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage continued with its strategy of holding open-air meetings in the hope of converting the inhabitants of south London to the idea of ‘Votes for Women’.

See also Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.

Kate Frye’s Diary: The Lead-Up To War: 16 July 1914

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's Diary on July 16, 2014

On 7 August 2014 ITV will publish an e-book, Kate Parry Frye: The Long Life of an Edwardian Actress and Suffragette. Based on her prodigious diary, this is my account of Kate Frye’s life and is a tie-in with the forthcoming ITV series ‘The Great War: The People’s Story’. For details of the TV series and its accompanying books see here.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

Kate was at this time 36 years old, living in a room at 49 Claverton Street in Pimlico and working in the Knightsbridge headquarters of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was now nine years since she had become engaged to (minor) actor John Collins. Her father died in March 1914 and her mother and sister, Agnes, now all but penniless, are living in rented rooms in Worthing. John has a room along Claverton Street, at number 11.

Thursday July 16th 1914

Jobs and writing. John in in the morning. Out together at 1.30 and lunch at Slaters. Bus to the Office and John went in with a message and then joined me at the Tube and we went to Hammersmith and then train to Isleworth and we bill distributed until 6. It was very hot and we both got so tired. John was quite exhausted – says he couldn’t do my work. We got the Townsfolk – the Brewery people and the Pears soap people so did it thoroughly – 1000 handbills.

Then train to Hammersmith and just caught a nonstop train to Victoria and rushed in to change. Got in 7.45 – and was out again at 8 in my best and we went as hard as we could to the Shaftesbury Theatre to see ‘The Cinema Star’. Had Dress Circle seats. We were about 10 minutes late, but really we had enough. It is rot and there is very little real fun. It is a long time since I saw a London Musical comedy. I don’t think they improve. Miss Ward and Miss Cicely Courtneidge were the stars.

Supper at the Corner House. I felt deadly tired. All the world is now mad over prize fighting – Gunboat Smith v Carpentier. It was a sort of Mafeking night. We caught the 12.10 train from Charing Cross. Had to walk from Victoria and got in at 12.45.

Kate and John presumably stood at the Pears Soap factory gates, handing out handbills advertising the ‘Votes for Women’ meeting the New Constitutional Society was holding the next day in Upper Square, Isleworth. The brewery they also canvassed was probably the Isleworth Brewery in St John’s Road.

”The Cinema Star’ had opened on 4 June and starred Jack Hulbert and Fay Compton as well as Cicely Courtneidge and Dorothy Ward. The Shaftesbury Theatre was owned by Cicely Courtneidge’s father. With Harry Graham, Jack Hulbert had adapted the play from a German comic opera, ‘Die Kino-Konigin’, and it played very successfully, despite Kate’s verdict of ‘rot’, until the outbreak when anti-German sentiment resulted in its abrupt closure. Cicely Courtneidge and Jack Hulbert married in 1916.

Carpentier (left) and Gunboat Smith fighting on 16 July 1914 (image courtesy of boxingshots.tumblr.com)

The American boxer, Gunboat Smith, had that evening fought the French champion, Georges Carpentier, at Olympia for the ‘White World Heavyweight Championship’. Smith was disqualified in the sixth round. Kate had good reason to describe street celebrations as ‘a sort of Mafeking night’. She had been in the Criterion Theatre on 18 May 1900 – when the relief of Mafeking was announced during an interval. By the time she left the theatre the streets of London were, as she put it, ‘alive with revelry’. You will be able to read all about Kate’s early life in the forthcoming e-book.

See also Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.

Kate Frye’s Diary: The Lead-Up To War: 15 July 1914

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's Diary on July 15, 2014

On 7 August 2014 ITV will publish an e-book, Kate Parry Frye: The Long Life of an Edwardian Actress and Suffragette. Based on her prodigious diary, this is my account of Kate Frye’s life and is a tie-in with the forthcoming ITV series ‘The Great War: The People’s Story’. For details of the TV series and its accompanying books see here.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

Kate was at this time 36 years old, living in a room at 49 Claverton Street in Pimlico and working in the Knightsbridge headquarters of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was now nine years since she had become engaged to (minor) actor John Collins. Her father died in March 1914 and her mother and sister, Agnes, now all but penniless, are living in rented rooms in Worthing. John has a room along Claverton Street, at number 11.

Wednesday July 15th 1914

Writing in the morning. John in at 11.30. Jobs. Out 1. Lunch together at Slaters. Coming out we met one of John’s Brother Officers when he was in the Field Artillery – Mr Graham. I have not seen him since the day we met at Burnham but he remembered me instantly. ‘Why, we went yachting’, he said. He is very nice looking.

Then John saw me off at Victoria for Lordship Lane – and though we asked two officials the train dashed on and landed at Crystal Palace. I was mad. Had to wait some time to get back – then a long walk to find Mrs Melling 75 Underhill Road and the meeting was half over. Miss McGowan had organised it and I had asked some of my new Peckham People and wanted to go to see them and because the Rev Hugh [Chapman] was down to speak – but I felt I was not going to meet him and he was not there. Ill and has had to go away. Miss McGowan was in the Chair, Mrs Chapman speaking. A very fine meeting, about 50 people there, but very few would join.

It started to pour with rain, but I had my coat and flew for a train and when I got out near home it was stopping a bit.

John was watching for me and came in with me while I tidied myself. He had changed. Then bus to Charing Cross – walked to the Popular had dinner and then to the St James’s Theatre to see ‘An Ideal Husband’. George Alexander not in it, and some one else playing Phyllis Neilson Terry’s part. It was a most cruel and awful performance – vilely and atrociously produced and most of them were in fits of laughter.

As for the play I could hardly sit it out – such Anti-suffrage old fashioned twaddle – as for the last act – tosh. I rose up and tramped out before the curtain fell. If I had paid for my seat I should have fussed. We were simply prancing with disgust. I never did like Oscar Wilde, but this play is the limit. Back by bus from the usual spot.

John Collins had, as a very young man, fought in the Boer War and ever since, as well as being an actor, had been a member of the Territorial Army – hence Kate’s mention of a ‘Brother Officer’. It was now not long before he would be involved in another war.

The New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage was clearly concentrating a good deal of its effort at this time on wooing the inhabitants of Peckham and East Dulwich. Kate had organized an open-air meeting in the centre of Peckham a couple of days ago – today’s was what was termed a ‘drawing-room meeting’ – in the home of a sympathiser. The Rev Hugh Chapman, whom Kate was keen not to miss, was the brother-in-law of the NCS president and was the vicar of the Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy. Kate was somewhat enamoured of him. For full details of her past – somewhat surreal – encounters with him see Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary.

The St James’s Theatre was in King Street, off St James’s Square, and in 1914 was owned and managed by Sir George Alexander. ‘An Ideal Husband’opened on 14 May 1914 and closed on 24 July. The critics were rather more sympathetic to the production than was Kate. But then most were probably not suffragists! As Kate remarked, at least she – and, presumably, John – had not had to pay for their tickets. As members of the Profession they usually received complimentary tickets whenever they asked for them which, given that they were both addicted to theatre-going and relatively impecunious, was just as well.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.

Kate Frye’s Diary: The Lead-Up To War: 14 July 1914

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's Diary on July 14, 2014

On 7 August 2014 ITV will publish an e-book, Kate Parry Frye: The Long Life of an Edwardian Actress and Suffragette. Based on her prodigious diary, this is my account of Kate Frye’s life and is a tie-in with the forthcoming ITV series ‘The Great War: The People’s Story’. For details of the TV series and its accompanying books see here.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

Kate was at this time 36 years old, living in a room at 49 Claverton Street in Pimlico and working in the Knightsbridge headquarters of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was now nine years since she had become engaged to (minor) actor John Collins. Her father died in March 1914 and her mother and sister, Agnes, now all but penniless, are living in rented rooms in Worthing. John has a room along Claverton Street, at number 11.

Tuesday July 14th 1914

Felt much better. what a relief – I was bubbling over with the joy of life. John came in before I had finished dressing but as I had to go out I left him at work on his Typewriter finishing something for the afternoon, and I went off to the Office, taking my dress for the afternoon with me.

Helped arrange things for the afternoon – and John came and he helped. Then when I could get away I changed and he and I went out to lunch and then back at 2.15 for the Summer Sale and Tea at the [ew].C[onstitutional] Hall. His work was to raffle signed photographs and mine to tie up parcels. But I never tied up one – the Palmist failed and I had to Palm – I hated it, but I really had quite a good time. Miss Lena Ashwell opened the Sale and though there did not seem many people we made quite a lot of money.

Mr Grein came straight from the Haymarket Theatre and the first Public Performance of ‘Ghosts’ as it has now been Licensed and had his hand read. But it was really very funny as he seemed to want to talk more about me – told me to go and see him – gave me his card, and said he liked my ‘eye’.

Gladys [Wright] was quite put about, ‘of course you will be leaving us now’ etc. She is quaint. But I do think the vain little man took rather a fancy to me and I imagine he is always on the look out for people likely to do him credit. I played up rather a game with him, but he quite took it all in. John was awfully upset.

John and I had tea together, and I think he enjoyed himself – he wore a new suit which was quite a success. We left soon as we could – rushed home and just tidied ourselves but no time for much – then out – no time for dinner – but straight to the Haymarket Theatre – Balcony stalls to see ‘Driven’. I enjoyed it immensely – beautifully produced and Alexandra Carlisle looking a perfect picture and greatly improved in her art and Owen Nares a fine actor – simply delightful in a most difficult part. Aubrey Smith as usual but good. The last act is idiotic, of course. John and I are certainly leading the gay and reckless life.

To supper at the Corner House. Waited for the last bus, but must just have missed it. Then found we had missed the last to Victoria – so made for the Underground. It had started to pour with rain by then and John in his new suit. We just caught the last train 12.20 and had to walk from Victoria, but fortunately the rain had not reached this district.

Burberry shop, Knightsbridge. The offices of the NCS were on the ground floor inside this building. An arcade originally ran through – with the entrance just about where the bus is in this photo. Off the arcade were a number of small shops and offices

The New Constitutional Society’s Hall was close to their Office, inside Park Mansions Arcade in Knightsbridge. This is now the site of the Burberry Menswear Department (see ‘Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Frye and Knightsbridge’ ). Kate had developed her skill as a Palmist in her youth – in lieu of the more conventional accomplishments expected of a young woman – such as piano playing, singing, or reciting. In her early involvement with the women’s suffrage movement she had often, as a volunteer, provided palm-reading entertainment at bazaars and dances. (See ‘Palmist at the Women’s Freedom League Fair).

Lena Ashwell was a leading member of the Actresses’ Franchise League and, over the years had opened many a suffrage bazaar and fair. A month from now she would be the instigator of the Women’s Theatre Camps Entertainments and of the Women’s Emergency Corps.

On Sunday 26 April 1914 Kate had been in charge of the box office at the Court Theatre (later the Royal Court) when J.T. Grein staged a private performance of Ibsen’s ‘Ghosts’ as a fund-raising event for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. This, of course, was before the Lord Chamberlain had removed his censorship of it by, as Kate explains, granting the play a performance Licence. Dutch-born Grein was a champion of European theatre.

‘Driven’, on the other hand, was a rather English comedy by E. Temple Thurston. The play’s run at the Haymarket came to an abrupt end at the outbreak of war – but in December was staged on Broadway, with Alexandra Carlisle again in the cast. The producer was Charles Frohman, with whose company Kate had had her first professional engagement ten years or so previously.

See also Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.

Kate Frye’s Diary: The Lead-Up To War: 9 July 1914

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's Diary on July 9, 2014

On 7 August 2014 ITV published an e-book, Kate Parry Frye: The Long Life of an Edwardian Actress and Suffragette. Based on her prodigious diary, this is my account of Kate Frye’s life and was a tie-in with an ITV series ‘The Great War: The People’s Story’. For details of the TV series and its accompanying books see here.

Back in 2014, as a lead-up to publication, I sharee with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. Through her day-to-day experience we can see how the war stole up on one Everywoman.

Kate was at this time 36 years old, living in a room at 49 Claverton Street in Pimlico and working in the Knightsbridge headquarters of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was now nine years since she had become engaged to (minor) actor John Collins. Her father died in March 1914 and her mother and sister, Agnes, now all but penniless, are living in rented rooms in Worthing. John has a room along Claverton Street, at number 11.

‘Thursday July 9th 1914

Hard at writing from 10 to 1. John came in and we went out together to lunch at Victoria. Then I went off to Hounslow by train and canvassed all up and down both sides of the High Street and all over the place, and at 6 o’clock at Parke Davis Dye works as the people came out.

Then a train back to Hounslow and train to Victoria and bus. In at 7.30. J. was watching at his window and saw me get out of the bus and came in with me and waited until 9 – when he was very good and went off and got supper by himself. I was so dead beat I felt I could not turn out again so ate some bread and cheese and fell into bed.’

Was Kate canvassing these shops on 9 July 1914? (Image courtesy Local Studies, Houslow Library Services)

Kate’s canvassing in Hounslow was for the purpose of drumming up attendance of a ‘Votes for Women’ meeting she is to hold tomorrow in the Broadway.

As WSPU militancy became even more intense the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage held to its principle of campaigning in a democratic manner. This may now be thought boring – failing to provide news fodder for the press then and for bloggers now – but it was non-militant political lobbying that in the end won women the vote.

In the few days previous to 9 July 1914 WSPU supporters had, besides continuing with their campaign of arson, concentrated their attention increasingly on the King and the Church. A portrait of the King by Sir John Lavery had been damaged in the Royal Scottish Academy and a few days earlier when the King had visited Nottingham a well-known suffragette had been arrested carrying a suitcase containing bomb-making equipment. On 1 July there had been a disturbance during the enthronement of the new Bishop of Bristol and on 5 July Mrs Dacre Fox had interrupted the Bishop of London during a Westminster Abbey service – asking him to prevent forcible feeding. She was a prisoner on the run, who had been released from prison under the Cat and Mouse Act, and was promptly re-arrested outside the Abbey.

Kate must surely have a taken a bus to the Parke Davis dye works, which was quite a way down the Staines Road. [The site at 581 Staines Road, long ago rebuilt by Parke Davis, is now used by the Home Office as an immigration centre.] Kate was well used to standing at factory gates handing out handbills – hoping to entice the workers to her meetings. We shall see tomorrow how successful her canvass had been.

See also Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary.

Kate Frye’s Diary: The Lead-Up To War: 3 July 1914

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's Diary on July 3, 2014

On 7 August 2014 ITV will publish an e-book, Kate Parry Frye: The Long Life of an Edwardian Actress and Suffragette. Based on her prodigious diary, this is my account of Kate Frye’s life and is a tie-in with the forthcoming ITV series ‘The Great War: The People’s Story’. For details of the TV series and its accompanying books see here.

As a lead-up to publication I thought I’d share with you some entries from Kate’s diary from the month before the outbreak of war. She was at this time living in Claverton Street in Pimlico and working in the Knightsbridge headquarters of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was now nine years since she had become engaged to (minor) actor John Collins. Her father died in March 1914 and her mother and sister, Agnes, now all but penniless, are living in rented rooms in Worthing.

Friday July 3rd 1914

It poured early and then drizzled. John with me to Victoria where I was to meet Miss Arber at 11. Together to Peckham where we canvassed [for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage]. I was quite glad of a coat I had taken for the rain. We had lunch together and back to Victoria.

I came straight in by bus and packed up my things. John arrived at 4 – he had been about all day so I sent him off to pack and then met him at no 11 [Claverton Street, Pimlico] with my luggage and we took a bus to Victoria and caught the 4.30 train to Worthing.

We toiled to Milton St with our luggage – they were surprised to see us so early. Agnes looks better, but Mother looks so ill, I think, and seems quiet and depressed. John has a bedroom at the end of the road. It is ever so cold here.

It was in the day’s paper – the death of Joseph Chamberlain. He has been a name only for many years – but I can remember him as a great power – before his Tariff Reform days and the consequent breaking up after the disappointment of defeats.’

Kate (and her father, who had been a Liberal MP in the 1890s, did not support Joseph Chamberlain’s Liberal Unionists. For a post describing how Kate campaigned for the Progressive Liberal candidate at the 1907 LCC election see here.

See also Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: Buckingham Palace, 21 May 1914

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 21, 2014

A hundred years ago today, on 21 May 1914, having failed to influence the government, Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, decided to appeal directly to the King. Kate Frye, although not a militant suffragette, was there – outside Buckingham Palace – to witness the scene. This is the copy of the Daily Sketch that she bought that day and kept all her life.

The following is Kate’s diary entry:

‘Thursday May 21st 1914

To Office.Then in the afternoon I went to Buckingham Palace to see the Women’s deputation – led by Mrs Pankhurst which went to try and see the King. It was simply awful – oh! those poor pathetic women – dresses half torn off – hair down, hats off, covered with mud and paint and some dragged along looking in the greatest agony. But the wonderful courage of it all. One man led along – collar torn off – face streaming with blood – he had gone to protect them. Fancy not arresting them until they got into that state. It is the most wicked and futile persecution because they know we have got to have ‘Votes’ – and to think they have got us to this state – some women thinking it necessary and right to do the most awful burnings etc in order to bring the question forward. Oh what a pass to come to in a so-called civilised country. I shall never forget those poor dear women.

The attitude of the crowd was detestable – cheering the police and only out to see the sport. Just groups of women here and there sympathising, as I was. I saw Mrs Merivale Mayer, Miss Bessie Hatton and a good many women I knew by sight. I stayed until there was nothing more to be seen. The crowds were kept moving principally by the aid of a homely water cart. It was very awful. Mrs Pankhurst herself was arrested at the gates of the Palace. I did not see her but she must have passed quite close to me.

I went to Victoria and had some tea and tried to get cool, but I felt very sick. The King could have done something to prevent it all being so horrible – he isn’t much of a man. Back by bus [to the office of the New Constitutional Society where she was working]. They [Alexandra and Gladys Wright, friends and colleagues ] wanted to hear about it, but they don’t take quite the same view of it that I do. They seem so ‘material’ in all their deductions – it’s all so tremendously more than that.’

For much more about Kate Frye and her diary – published as Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s suffrage diary – click here

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Frye And The Problem Of The Diarist’s Multiple Roles

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 7, 2013

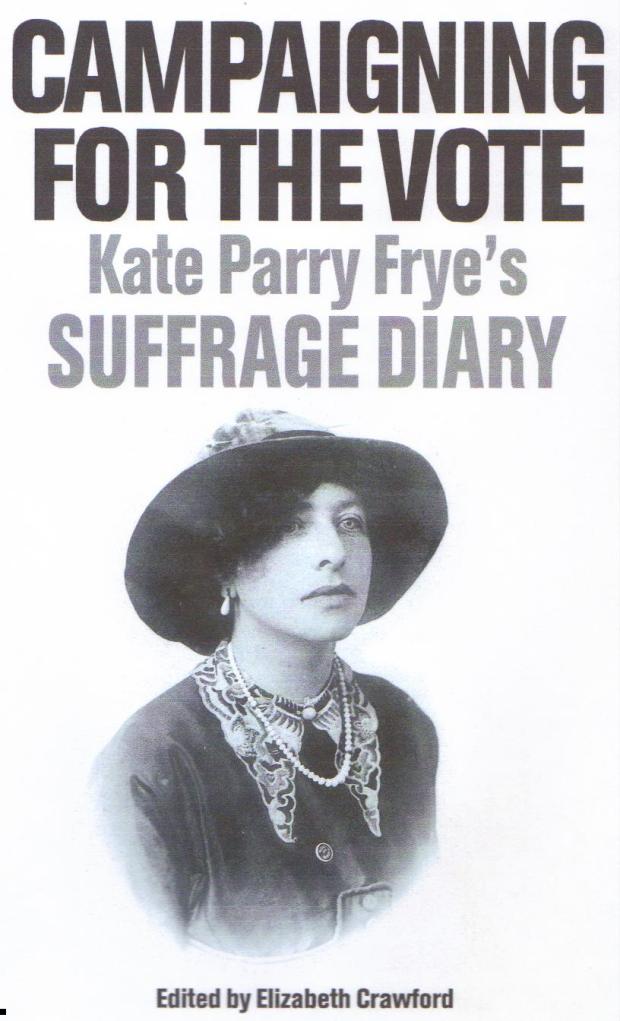

In the following article I discuss the ethics of ‘mining’ the diary that Kate Parry Frye kept for her entire lifetime in order to re-present her in one role only– as a suffragist. The piece is based on a paper I gave at the 2011 Women’s History Network Conference. Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary is published by Francis Boutle Publishers at £14.99

Kate Parry Frye[1] was a diarist. She was also a girl, a young woman, a middle-aged woman, an old woman, a daughter, a sister, a cousin, a niece, a fiancée, a wife, an actress, a suffragist, a playwright, an annuitant, a letter writer, a Liberal, a valetudinarian, a playgoer, and a shopper. She was a rail traveller, a bus traveller, a tube traveller, a reader, a flaneur, a friend, and a political canvasser. She was a diner – in her parents’ homes, in digs, in hotels, in restaurants, in cafés and later, of necessity, a diner of her self-cooked meals. She was an enthusiast for clothes, a keeper of accounts, a reader of palms, a dancer, a holidaymaker, a visitor to the dentist, to the doctor, an observer of the weather, a worker of toy theatres, a needleworker, an animal lover – indeed dog worshipper – a close observer of the First World War and then of the Second.

She was radio listener, a television viewer, a neighbour and, finally, a carer, recording in detail the effect on her husband of the remorseless onset of dementia and the disintegration of his body and mind. Every one of these roles is played out in minute detail in the diaries Kate Frye kept for 71 years, from 1887, when she was 8 years old, until October 1958, barely three months before her death in February 1959.[2]

Moreover, each role has its variations, depending on time and place. Thus, for example, as a middle-class daughter, Kate Frye played the pampered child, the indulged adolescent and, later, the resentful adult.

She was for many years supported financially and lived comfortably. In early womanhood she was afforded considerable freedom, her parents allowing her, indeed encouraging her, to train as an actress and to travel around Britain and Ireland with a repertory company. When that venture proved unprofitable she was able to return to life as a daughter-at-home, a role that appears to have combined the minimum of domestic chores with the maximum of freedom. Until December 1910 the family divided their time between two homes – a house, later a flat, in North Kensington and ‘The Plat’, a large detached, much-loved house on the river at Bourne End in Buckinghamshire.

But Kate Frye was also the daughter of a man whose business failed, whose lack of financial acumen she judged harshly, forcing as it did her mother, her sister and herself to leave their homes and sell all their possessions. Before 1910 there had been periodic indications of financial instability, when, for instance, ‘The Plat’ was let out for the summer, but Kate’s father failed to take his wife and daughters into his confidence, making the ultimate catastrophe all the more shocking. To Kate’s shame the family subsequently relied on the charity of her mother’s wealthy wine-merchant relations, the Gilbeys.[3] Her role in this performance might be studied, shedding as its does a clear light on the precarious reality of the long Edwardian summer. One year Kate could take for granted a life of boating and regattas, dressmakers, cooks and maids, the next she was living in dingy digs, attempting to raise money by hawking the family jewellery and old clothes around shops, while wondering if her relations had remembered to send the remittance and what she would do if they forgot..

Or perhaps one could look through Kate Frye’s eyes at the reality of working the towns of Edwardian England, Scotland and Ireland as an actress.

For instance, between September and December 1903 she was a member of a Gatti and Frohman touring production of J.M. Barrie’s Quality Street and writes in considerable detail of company train travel, theatrical lodgings and the other members of the cast, among who was a young May Whitty. Kate was paid £2 a week and includes in the diary some weekly accounts, which could be studied in conjunction with the management’s financial accounts of the tour.[4] Or her diary could be used to give an insight into the issue of class and gender in the Edwardian theatre; Kate’s experience does not indicate that family and friends felt that her new role was in any way either imprudent or declassé.[5] Or her diary might be used to research the behind-the scenes world of post-1918 theatre, as Kate reports on her husband’s attempt to earn a precarious living as actor and stage manager.[6] Kate’s involvement with theatre saw her performing on both sides of the stage – in her role as an actress and, in the auditorium, as a spectator – and her diary might also be used to study of the habits of playgoers over the decades, recording as it does her comments on the vast number of performances she attended. On occasion she thought nothing of seeing two plays in one day.

Kate kept a separate record of all the plays she saw – including Elizabeth Robins’ ‘Votes for Women!’

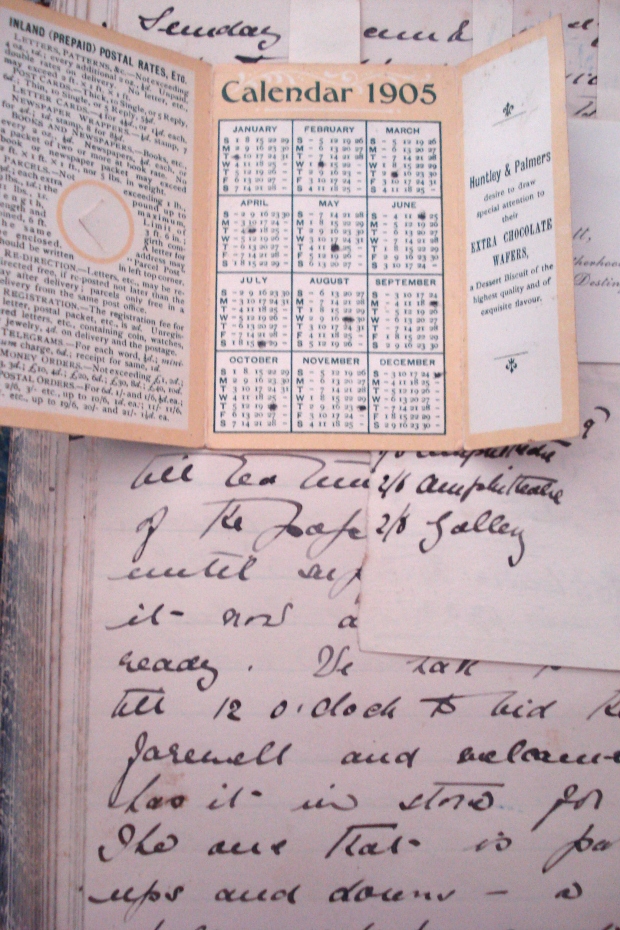

Or perhaps one could use her diary to study the nature of ill-health, real or perceived. Menstrual pain – ‘the rat pain’ – lurks behind some of Kate’s continuous complaints of ‘seediness’ and included in some of the diaries are small yearly calendars with the date of each menstrual period marked in pencil.

But the feeling of ill-health suffered by Kate, by her elder sister, Agnes,[7] and their mother was due to more than menstruation. For weeks at a time, year after year, one or the other, or all three, are confined to their beds. The doctor calls – and is paid – medications are prescribed and taken. For some of the time ‘seediness’ is endured and Kate, at least, gets on with things. It is noticeable that when she has an active life to lead, whether on tour as an actress or as a suffrage organiser, she makes many fewer complaints of ill-health. It is difficult to avoid the thought that some, at least, of the malaise was due to depression occasioned by lack of occupation. Kate did, after all, continue fit and healthy until she was 80. The diary could be read and edited to bring this aspect of her life to the fore, studying the links, in the first 50 years of the 20th century, between status, expectation and occupation – or lack of it – and mental and physical wellbeing Certainly Kate’s sister, who never worked and appears to have had few interests, seems to have given up on life, spending much of her later years in bed and drifting into death. However, although these aspects of Kate Frye’s life are intriguing, it is for her involvement with the Edwardian suffrage movement that she is now likely to be remembered. For Kate Frye’s diaries have been directed, by chance, towards an editor whose research interests centre on suffrage.

Kate was what one student of diary writing terms a ‘chronicler’, that is her diary was a ‘carrier of the private, the everyday, the intriguing, the sordid, the sublime, the boring – in short a chronicle of everything’ and in its extent is not a little daunting.[8] But, reading the volumes covering the years prior to the First World War, one quickly realises that involvement in one of the major campaigns of the day provided Kate’s life – and her diary – with a focus. For the Frye family’s descent into near, if genteel, destitution coincided with the growth of the suffrage movement, which subsequently provided Kate with employment. Although she was untrained for any career other than acting, which she had found, in fact, did not pay, work of a political nature was not outside her sphere of knowledge, for one of her earlier roles had been that of the daughter of an MP. Kate’s father, Frederick Frye, had been the Liberal member for North Kensington from 1892 to 1895 and an interest in politics was taken for granted within the family. Over the years Kate had helped her mother with the regular ‘At Homes’ held for the Liberal ladies of North Kensington and had accompanied her father to many a political meeting.

The diary entries trace her growing involvement in the suffrage campaign, from participation in the first NUWSS ‘Mud March’ in early 1907, through her performance as a palm reader at numerous fund-raising suffrage bazaars and dances, attendance at meetings of the Actresses’ Franchise League, marching in all the main spectacular processions, stewarding at meetings, bearing witness to the ‘Black Friday’ police brutality in Parliament Square on 18 November 1910, to her employment, from early 1911 until mid-1915, as a paid organiser for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. The diary, as edited as Campaigning for the Vote, highlighting the detail Kate provides of daily life as a suffragist and illustrated with the wealth of suffrage ephemera with which she embellished the original, is an interesting addition to published source material.

But what are the ethics of spotlighting this one role – or any role – from a lifetime performance? Kate’s diary seems to lend itself quite naturally to a style of editing that sets her entries, replete with delightfully quotidian suffrage detail, within a linking narrative, explaining the greater campaign and providing information on people she meets in the course of her days. But, increasingly uneasy, the editor of Kate Frye’s diary felt it necessary to take soundings from commentators on diary writing in order to discover whether the perceived problem, that of highlighting only one of the diarist’s multiple roles – one of her many selves, is one that others have resolved.

Robert Fothergill’s Private Chronicles, published 35 years ago, is generally considered the earliest academic work to have made a serious study of diary-writing.[9] In his study Fothergill considered the diaries both of men and of women but since then much of the attention the genre has received has concentrated on diary writing by women. For in the 1980s and 1990s, with the growing interest in women’s history, academics such as Margo Culley, Cheryl Cline, Harriet Blodgett, Suzanne Bunkers and Cynthia Huff saw women’s diaries as an exciting new source through which to re-examine and re-envisage women’s lives.[10] As Bunkers and Huff wrote, ‘Within the academy the diary has historically been considered primarily as a document to be mined for information about the writer’s life and times – now the diary is recognized as a far richer lode. Its status as a research tool for historians, a therapeutic instrument for psychologists, a repository of information about social structures and relationships for sociologists, and a form of literature and composition for rhetoricians and literary scholars makes the diary a logical choice for interdisciplinary study.’[11] These writers use metaphors such as ‘weaving’, ‘quilting’, ‘braiding’ and ‘invisible mending’ to describe the way in which a woman fashions her diary, a diary of dailiness rather than of great moments. But that ‘weaving’ or ‘quilting’ or ‘braiding’ lies at the heart of the problem. Is it legitimate to unravel this self-construction and fashion it into something else?

That question might be answered quite simply by a judgment made in 1923 by Sir Arthur Ponsonby and much quoted, even by the American women historians of the 1980s. For in English Diaries, Ponsonby was adamant: ‘No editor can be trusted not to spoil a diary.’[12] For his part, Robert Fothergill stated that the only respectable motive behind the amputation of a diary was the desire to make it readable – ‘commonly the abridgement or distillation of an unwieldy original, through the elimination of whatever was considered stodgy, pedestrian or repetitious’.[13] But such an ‘amputation’ is not unproblematic, for what might be considered stodgy and pedestrian to one reader, or in one decade, might be lively and interesting to the next. To anyone interested in the daily life of a suffragist, even the repetitions in Kate Frye’s daily life are revealing. Cheryl Cline elaborated Fothergill’s point, writing, ‘The most sensitive and careful editors, in cutting what they may feel unimportant, irrelevant, repetitious or even “too personal”, walk a very fine line. They may end up, for all their good intentions, ruining the work. Many editors have been neither sensitive nor careful. Editors have cut manuscripts they felt were too long, padded those they thought too short; re-arranged material to suit themselves; bowdlerized writings which revealed the less-than-perfect character of their authors. Too often, they have destroyed the originals once the edited version was published’.[14] So reservations about editing Kate Frye’s lifetime performance to refashion it as a ‘suffrage diary’ are, perhaps, not unjustified, although Kate Frye’s published diary will be neither ‘padded out’, or ‘bowdlerized’, nor will the original be ‘destroyed’. However, the charge of ‘re-arrang[ing] material’ is, perhaps, not inappropriate. It is not that the published entries will have been re-arranged, rather they will have been accorded a prominence they did not have in the original.

It is worth remarking that much of the academic literature on diary writing concentrates on the published diary.[15] There appears to be little recent consideration of the ethics of, as Bunkers and Huff put it, ‘mining’ a manuscript diary for the light it throws on particular aspects of the past, other than the difficulty this creates for those critiquing diary writing per se. Indeed, these authors appear to suggest that it was only in the past that a diary would be treated in this way. Fothergill touched on this point, condemning most severely ‘the ravages of editors, committed in, amongst other things, the name of thematic unity, writing that, from the point of view of his study of diaries, ‘A fatally damaging editorial approach is the subordination of a diary’s general interest to a specialist one, retaining only what is of use to the political or religious historian, for example.’[16] However Cheryl Cline has taken a more tolerant attitude to this aspect of diary editing, commenting ‘The urge to make a “good story” out of a diary that seems rambling and disjointed…is the motive which guides many an editor’s blue-pencil. While many diaries..are written around a theme .. or an event .., most private writings are disjointed and far-ranging. In this case material may be extracted from them and shaped into a more cohesive narrative.’[17] She then cites, as a well-known example of editing for story, A Writer’s Diary, compiled from Virginia Woolf’s diary by Leonard Woolf.[18] Kate Frye’s diary, edited to tell her suffrage story, might, therefore, be said to be keeping exalted company.[19] However it is certainly true that since the middle of the 20th century, the move in diary editing has been towards the unabridged text, complete with full scholarly apparatus. But Kate Frye would never be given that kind of treatment. So is it better to give a wider audience a ‘ravaged’ text – or to leave it, unpublished, in its wholeness on the archive shelf? An argument for leaving it untouched might well be made by the academics who have stressed the importance of the diary as a complete self-construct, a form of autobiography or life writing.[20] The author has considerable sympathy with this viewpoint, while recognising the specific interest to students of women’s suffrage in retelling the story of Kate’s suffrage years.

But perhaps, if theory cannot provide a clear answer, we should look for guidance to the diarist herself. What would Kate Frye have liked done with her text? Although she has been dead for 50 years that text is still alive with her personality and it is not inconceivable that someone who put so much of herself onto the page, developing her writing skill as she shaped her life, would have been happy to have known that she would one day reach out to a wider audience.

In this context it is worth considering for whom Kate Parry Frye had been performing. Most certainly in her diary she acted out her days for herself. From her very early years the diaries had become an essential part of her life. On occasion she discusses whether to bring her diary writing to an end, but always decides to carry on. Until mid-1916, utilising the format that Cynthia Huff describes as ‘self-determined,’ Kate wrote her entries in a large ledger-type book, embellishing them with the addition of relevant ephemera.[21] When, on 16 November 1913, on reaching the end of yet another of these books, she wrote ‘And so I have come to the end of this volume with no book to go on with though I have written to Whiteleys.[22] It would be more sensible to leave off writing a diary – at any rate such an extensive one – but more lonely’. But she did acquire another volume from Whiteleys, although that was to be the last of this kind and she afterwards continued her record in purpose-made diaries, adhering, more or less, to the space allocated for each day and no longer inserting additional material..

So that is one explanation as to why Kate kept her diary; it was her daily companion. In it she depicts herself as slightly aloof from her parents, sister and husband, her abilities unappreciated. As Fothergill has observed, ‘the function of the diary is to provide for the valuation of [self] which circumstances conspire to thwart.’[23] Financial circumstances certainly thwarted Kate’s ability to maintain the class position that for some years she had enjoyed, but in her diary she could continue to present herself as an aspiring member of the upper-middle middle class, although, after 1910, always conscious of the financial chasm that existed between this idea of herself and the reality. On March 17th 1913, when meeting her Kensington contemporaries, she notes: ‘They all seemed so smart and so well dressed and so of a different life – the life really that we have left behind. Oh what a difference money makes.’ Lack of money is a recurrent theme, although in her entry for 22 December 1913 she does try to overcome her regrets, writing, ‘I always feel given nice clothes … I could look nice and attractive. I hate being shabby. It is bad enough to grow old, but to grow dowdy with it, but what can one do without money and lots of it. I do seem to grumble. I seem to forget I am aiming for “goodness” in an advanced and suffrage meaning, and that really any other state is very petty.’ It was not that she struck extravagant poses in her diary, rather that there she felt that there her days were being re-enacted in front of an appreciative audience – herself.

Kate seldom dwells on the act of diary writing, but on Sunday 8 February 1914 was prompted to record:

‘I am reading ‘The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff’. It is too absolutely interesting for words – and yet all so natural….it isn’t far off me in the inmost soul. Only in performance she was a genius – she could do – I can only dream that I could and do – accomplish. It made me want to read my old Journals but how tame after Marie’s. I was always for putting time and place and leaving out the really interesting bits in consequence – though I sometimes think I catch atmosphere. That is the disadvantages of writing a diary instead of a Journal – one only ought to write when one is inspired and at the moment the feeling or idea strikes one – but with a diary the date and correctness is the thing.’[24]

Perhaps it is fortunate for us the Kate did not write what she terms a ‘Journal’; it is the ‘putting time and place’ that makes Kate’s diary so interesting.[25] We can sit with her on the tube or bus, travelling around London; we can reconstruct the route taking her from Notting Hill Gate to the Criterion Restaurant in Piccadilly for a meeting of the Actresses’ Franchise League – and then eavesdrop on the proceedings; we can go with her to Covent Garden to see the Russian Ballet – ‘as for M Nijinsky, well, words fail me’;[26] we can travel with her around the country roads of Norfolk, searching out suffrage sympathisers; and accompany her as she organises the transport of her boxes, a complicated business, to and from stations and ‘digs’ in the small towns of east and southern England.

For Kate Frye’s diary keeping makes no distinction between the daily chores – brushing her dog, having lunch, changing her books at Smith’s – and life-changing events. Even so, like all diarists, it is clear that she edited her day and, unsurprisingly, for her diaries had no locks, did not make explicit the details of everything that happened to her. For instance, it was only the reading of an entry in a post-Second World War diary that gave a clue to what lay behind her long association with – and eventual marriage to – John Collins, a fellow actor in the 1903 touring production of Quality Street, a relationship that, as presented in Kate’s words, seems rather puzzling. That post-war entry referred to the one for 20 September 1904, the day that Kate finally agreed to marry John. The entry itself is, naturally, of interest because she is writing of the day of her engagement but, when read in context, is constructed – or self-edited – so as not to include anything particularly revealing, merely that, after some, perhaps rather melodramatic, hesitation, Kate had finally acquiesced to John’s repeated offer of marriage. However, on re-reading the entry in the light of the later comment, a rather different story emerges. Kate’s words – ‘..I had to promise, it is the only right thing left to do …I couldn’t marry anyone else now, as he says. I have burnt my boats and no one must ever know that my real self is hesitating’ – appeared to be those of a woman who had realised that she had to make a decision, that she could no longer keep the man hanging on. But, alerted by the entry written nearly 50 years later, a re-reading reveals a rather different story. For, it transpires Kate had acted in such a way that ensured that, this time, she had to agree to marry John. It is hardly worth speculating on what actually had occurred, although in this entry Kate does write of passion and desire. In fact his lack of money, coupled with her lack of inclination, meant that it was a further 11 years before Kate and John married. Although she often debates with herself as to whether she can continue with the engagement, Kate feels unable to escape what she sees as her obligation. The story of that day in Croydon digs – with the landlady out shopping – is only one, albeit major, episode where the diarist, while ostensibly being frank, has not made all explicit.

There are doubtless very many other such occasions on which the doings of the self as portrayed in Kate’s diary do not reflect exactly the experience of the self that enacted them, the self of the diary having been refashioned by the diarist’s pen. For Kate Frye recognised her diary’s usefulness in providing her with the daily discipline of putting words on paper. Her diary is written in direct, colloquial prose. Her writing is fluent and she makes virtually no corrections. As we have seen, she was interested in ‘catching atmosphere’ and, although she never intended her diary for publication, she did aspire to literary success. Over many years she mentions time spent on ‘writing’ and a quantity of her manuscripts and typescripts, together with the rejection letters from agents and publishers, survive. Unsurprisingly, for one so enamoured of the theatre, these works are all plays, but only a one, co-written with John Collins, was ever published.[27]

Regretting as she did her lack of literary success, it is difficult to believe that she would be averse to seeing her words in print now.

Recognising the affection Kate felt for her diary and the time and care she had spent on shaping it, it is worth considering what she had thought might happen to it after her death. In fact her will reveals that the diaries were in effect her main bequest. She left the many volumes, together with the lead-lined bookcase in which they were kept, itself an indication of the concern she felt for their well-being, to the son of one of her cousins. That cousin, long dead, had been the only one of her relations to have had similar literary aspirations, albeit rather greater success. For, Abbie Frye was a prolific Edwardian novelist who wrote under the name ‘L. Parry Truscott’.[28] Kate had clearly wanted the diaries preserved and had not been worried at the thought of their being read by a member of the younger generation – and, by inference, a later general public. But would she have objected to being presented to the general public only in her role as a suffragist – for that is in effect how she is now re-created?

So let us now view the problem from the other side and consider the contribution that Kate Frye’s diary may make to our understanding of the suffrage movement and of the lives lived by its members. How does Kate’s diary stand among other diaries dealing with the suffrage movement? What makes it worth the trouble of editing and publishing? The main difference between the diary of Kate Frye and most others recording suffrage involvement that survive in the public domain is that the latter were written primarily because that involvement represented a singular experience, a highpoint in the diarist’s life. Thus, for instance, the militant campaign is well represented by diaries kept by imprisoned suffragettes, recording the horrors of forcible feeding.[29] For the constitutionalists, two diaries kept by Margery Lees have survived. Leader of the Oldham NUWSS society, she has recorded in one the work of the society and, in the other, gives an account of her participation in a great NUWSS event, the 1913 suffrage pilgrimage.[30]

Apart from that of Kate Frye, only a handful of other diaries with suffrage-related daily entries are known. Those of the delightfully Pooterish Blathwayts of Batheaston, father, mother and daughter, have proved an excellent source for researchers of WSPU personalities and of the militant campaign in Bath[31] and that of Dr Alice Ker provides short factual notes on the suffrage scene in Birkenhead and Liverpool.[32] The diary of Eunice Murray, a prominent Scottish member of the Women’s Freedom League, is in some ways comparable to that of Kate Frye, although the former’s comments on the suffrage campaign are more measured, while her actual accounts are less detailed.[33] Like Kate, Eunice Murray spoke at suffrage meetings but was not required to organise them and was certainly less concerned with ‘catching the atmosphere’ when writing up her diary entries. The diaries of the actress and novelist Elizabeth Robins (held in the Fales Library, New York) record her involvement with the English suffragette movement but, again, although she contributed as a speaker, she was not working at the suffrage ‘coal face’, as it were. None of these diaries, suffragist or suffragette, has yet been published. Excerpts from the diaries of Ruth Slate and Eva Slawson make clear their interest in the Cause and, interwoven with material from their letters, have been published, but within the overall narrative of their lives and concerns suffrage plays only a relatively minor part.[34]

Kate’s diary is valuable because it records her continuous involvement as a foot soldier in the suffrage campaign. She is writing without the benefit of hindsight, recording the inconsequential details of, say, finding a chairman for a suffrage meeting in Maldon or dealing with an imperious speaker in Dover, as well as the rather more momentous suffrage occasions, such as waiting on the platform at King’s Cross station as the train carrying Emily Wilding Davison’s coffin is about to leave for Morpeth. We can trace day by day, week by week, Kate’s growing participation in the movement, reflecting as it does both the increasing publicity given to and acceptance of the suffrage campaign and the decline in her family’s fortunes.

In 1913 Kate was campaigning for the New Constitutional Society in Whitechapel, distributing NCS leaflets translated into Yiddish

Although we cannot say that she became an increasingly militant (although never actively militant)[35] supporter because she regretted her lack of education, in the very first entry in which she refers to suffrage, on 3 December 1906, she writes: ‘I really do feel a great belief in the need of the Vote for Women – if only as a means of Education. I feel my prayer for Women in the words of George Meredith: “More brains, Oh Lord, more brains” ‘[36] – or, again, in 1914, ‘Neither do I understand why I was born if I wasn’t to be educated.’ Kate’s education had been that considered suitable for her gender and class. She did not attend school, but until she was 16 was visited by a ‘daily governess’, although visits were not invariably daily. After that she received somewhat erratic tuition from teachers of French and music. Nor can we say she became a suffragist because she lacked economic power. But she was certainly aware that those two factors – a lack of education and a lack of funds – made life as a woman without the shelter of family money, or the ability to earn her own, very difficult.

Like so many other women at that time, Kate Frye saw the acquisition of the vote as one step towards autonomy. It is our luck that for a few years she attempted to solve her economic problem by propounding the political solution, that is, she earned a living, of sorts, by becoming a suffrage organiser. It is extra fortunate that she did so for a society, the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage, about which very little has hitherto been known. In fact Kate Frye’s diary contains more information about the NCSWS and more of the society’s ephemera than exists anywhere else.

Her elaboration of diary entries by the addition of leaflets advertising the suffrage meetings she attended, even on occasion leaflets she herself had arranged to have printed, and for the processions in which she took part, demonstrates how prominently the campaign figured in her life. Virtually no other ephemeral material is included during this period.

We need only look to the diary for the answer to the question as to whether Kate Frye would object to being remembered as a suffragist. For on ‘Sunday 10 February 1918’ she wrote, ‘One of my afternoon letters was to Gladys Simmons[37] in commemoration of the passing of the Franchise Bill. Haven’t had a single letter from anyone concerning it – I said I wouldn’t but it seems very strange – that someone hasn’t thought of me in connection with the work.’ Now that her suffrage diary is published, at last Kate Frye will ‘be thought of in connection with the work’ and be recognised as a suffragist.[38] However, the very act of publication highlights just this one of her many roles. Out of the multiplicity of Kate Frye’s self-constructions, it is the ‘self’ of her suffrage years that emerges. The reader will have to accept that ‘mining’ a diary in order to view an historical episode from a fresh angle may come at the expense of maintaining the integrity of the diarist’s conception of ‘self’.

Kate’s diary entry for 21 May 1914 in which she records witnessing the WSPU demonstration in front of Buckingham Palace

[1] Katharine Parry Frye (1878-1959), daughter of Frederick and Jane Kezia Frye. Frederick Frye was a director of a chain of licensed grocery shops, Leverett and Frye, a firm financed by the wine merchants W.& A.Gilbey, as a useful outlet for their wines. When Frederick Frye became an M.P., Gilbey’s took over the running of the business. The Irish branch still operates. Frederick’s father had been a ‘professor of music’ and for 64 years organist at Saffron Walden parish church. Jane Frye’s father was a Winchester grocer. In 1915 Kate married John R. Collins.

[2] In August 2010 correspondence on Guardian Online, which included contributions from members of the Women’s History Network, demonstrated that it is by no means unusual for contemporary women to keep daily diaries over decades of their lives..

[3] Kate’s Aunt Agnes (1834-1920, née Crosbie), her mother’s sister, was the widow of Alfred Gilbey (d. 1879). For details of the Gilbeys of Wooburn House, Wooburn, Buckinghamshire see B. B. Wheals (1983) Theirs were but human hearts: a local history of three Thameside parishes (Bourne End: H.S. Publishing). From their relatively humble origins the brothers Walter and Alfred Gilbey grew wealthy as they developed England’s largest wine merchant business, W. & A. Gilbey.

[4] ‘Accounts and Legal’, Quality Street tour accounts (Theatre Museum), cited in Tracy C. Davis (2000) The Economics of the British Stage 1800-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) p.217.

[5] For a discussion of the entrance of middle-class women into the acting profession see Tracy C. Davis (1991) Actresses as Working Women (London: Routledge) pp. 13-16.

[6] In the 1920s and 1930s Kate often joined her husband on tour. For instance, over many years she spent some time each year at Stratford-on-Avon, where her husband was stage manager for productions at the old Memorial Theatre.

[7] Agnes Frye (1874-1937)

[8] See T. Mallon (1995) A Book of One’s Own: people and their diaries (St Paul, Minn: Hungry Mind Press) p. 1.

[9] Robert A. Fothergill (1974) Private Chronicles: a study of English diaries (London: OUP).

[10] See Jane DuPree Begos (1977) Annotated Bibliography of Published Women’s Diaries (issued by the author); Margo Culley (Ed) (1985) A Day at a Time: the diary literature of American women from 1764 to the present day (Old Westbury NY: Feminist Press); Harriet Blodgett (1989) Centuries of Female Day: Englishwomen’s Private Diaries (New Brunswick, London: Rutgers University Press); Cheryl Cline (1989) Women’s Diaries, Journals and Letters: an annotated bibliography (New York and London: Garland Publishing); Harriet Blodgett (Ed.) (1992) The Englishwoman’s Diary (London: Fourth Estate); Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia A. Huff (1996) Inscribing the Daily: critical essays on women’s diaries (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press) Suzanne L. Bunkers (2001) Diaries of Girls and Women: a midwestern American sampler (London, University of Wisconsin Press).

[11] Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia Huff ‘Issues in Studying Women’s Diaries: a theoretical and critical introduction’, in Bunkers and Huff (Eds) Inscribing the Daily, p.1

[12] Sir Arthur Ponsonby (1923) English Diaries (London:Methuen & Co), p. 5.

[13] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p. 5

[14] Cline, Women’s Diaries, p xxvii-xxviii.

[15] Exceptions include Bunkers, Diaries of Girls and Women. See also Cynthia Huff (1985) British Women’s Diaries: a descriptive bibliography of selected 19th-century women’s manuscript diaries (New York: AMS Press).

[16] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p. 5.

[17] Cline, Women’s Diaries, p. xxviii.

[18] L. Woolf (Ed) (1953) A Writer’s Diary. Being extracts from the diary of Virginia Woolf (London, Hogarth Press).

[19] Although, after Leonard Woolf’s ‘dismembering’, the diaries were reconstructed, in five volumes, edited by Anne Olivier Bell.

[20] For instance, Martin Hewitt (2006) Diary, Autobiography and the Practice of Life History in David Amigoni (Ed) Life Writing and Victorian Culture (Aldershot: Ashgate).

[21] Huff, British Women’s Diaries, p xiv.

[22] Whiteleys was a large department store, which, when Kate wrote this 1913 entry, was in Queensway. The store’s owner, William Whiteley, ‘the Universal Provider’, had been a close friend of the Frye family and his murder and subsequent trial are recorded in detail in Kate’s 1907 diary.

[23] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p.82.

[24] .Marie Bashkirtseff, a young Frenchwoman, filled 85 notebooks with her journal, which was edited for publication after her death in 1884. An English edition, Mathilde Blind (Ed. and Trans) 1890, The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff (London: Cassell) 2 volumes. Philippe Lejeune has described the Journal as foreshadowing ‘a line of diaries where introspection, active contestation of the condition of women, and interest in writing stand out as defining features’, see Philippe Lejeune The “Journal de jeune fille” in Nineteenth Century France in Bunkers and Huff, Inscribing the Daily, p119.

[25] Some attention has been paid to this distinction by scholars of diary writing. Suzanne Bunkers, after initially believing that what distinguishes a journal from a diary is that the diary is ‘a form of recording events, and the journal is a form of introspection, reflection, and the expression of feeling’, comes to the conclusion that the distinction is untenable, see S. Bunkers, Diaries of Girls and Women, p 12.

[26] Diary entry for 9 July 1912.

[27] Katharine Parry and John R. Collins (1921) Cease Fire!: a play in one act (London: French’s Acting Editions).

[28] Gertrude Abbie Frye (always known as Abbie), later Mrs Basil Hargrave (1871-1936). The works of ‘L. Parry Truscott’ were mistakenly attributed to Katharine Edith Spicer-Jay in Halkett (1926) Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous English Literature, (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd), Vol 1. By 1926 ‘L. Parry Truscott’’s star had waned and Abbie, by now a widow, was vitually penniless. A considerable amount of information about the interesting life of Abbie Frye can be gleaned from Kate Frye’s diary.

[29] See the manuscript prison diaries of Mary Anne Rawle, Elsie Duval and Katie Gliddon (Women’s Library); the manuscript prison diaries of Olive Walton and Florence Haig (Museum of London); and the manuscript prison diary of Olive Wharry (British Library); The manuscript prison diary of Anne Cobden Sanderson (London School of Economics) has been edited by Anthony Howe but is, as yet, unpublished.

[30] Both Margery Lees’s diaries are held by the Women’s Library.

[31] The Blathwayt diaries are held in the Gloucestershire Record Office. See June Hannam ‘Suffragettes are Splendid for Any Work’: the Blathwayt Diaries as a Source of Suffrage History in Clare Eustance, Joan Ryan and Laura Ugolini (Eds.) (2000) A Suffrage Reader: charting directions in British Suffrage History (London: Leicester University Press).

[32] Dr Alice Ker’s diaries are held in a private collection.

[33] The manuscript of Eunice Murray’s diary are held at the Women’s Library, together with a bound copy of the Diary of Eunice Guthrie Murray, transcribed by Frances Sylvia Martin.

[34] T. Thompson (Ed.) (1987) Dear Girl: the diaries and letters of two working women (1897-1917) (London: Women’s Press).

[35] Kate Frye joined the WSPU in November 1910, after witnessing the ‘Black Friday’ demonstration, but was soon appointed as a paid organiser for the newly-formed New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage.

[36] The quotation is taken from Modern Love by George Meredith, first published in 1862.

[37] As Gladys Wright, she had been a very old Kensington friend of Kate Frye and hon. Sec. of the NCSWS.

[38] Campaigning for the Vote: The Suffrage Diary of Kate Parry Frye, is published by Francis Boutle

Campaigning For The Vote: Kate In Kent: Folkestone

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on April 17, 2013

In the course of the years 1911-1914 Kate Frye spent over 20 weeks organising the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage’s campaign in Kent. She recorded every detail of her daily life in the entries she made in her diary and a selection, relating to the conduct of the campaign, are included in Campaigning for the Vote.

In the course of the years 1911-1914 Kate Frye spent over 20 weeks organising the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage’s campaign in Kent. She recorded every detail of her daily life in the entries she made in her diary and a selection, relating to the conduct of the campaign, are included in Campaigning for the Vote.

Kate spent time in Ashford, Folkestone, Hythe and Dover, canvassing house-by-house and organising meetings in drawing-rooms and public halls.

Below are three samples of Kate’s Folkestone experiences.

Saturday October 21st 1911 [Folkestone: 4 Salisbury Villas]

Quite a mild day and needed no fire till evening but inclined to shower. I wrote letters – then at 11 to Mrs Kenny’s – 63 Bouverie Road, Folkestone.

She had asked me to lunch but Mrs Hill wanted me back again so, as there wasn’t much I could do, I just had a chat with her and Mrs Chapman, who is staying there, and came back again. Changed and got back to Mrs Kenny’s at 2.30 for her party at 4. Miss Lewis of Hythe took the Chair and Mrs Chapman spoke. There were between 70 and 80 people – mostly very smart – a military set. Mrs Kenny is very nice and Colonel Kenny is quite sweet. Some of the men were very amusing. I got a golf ball from one and sold it for 2/6. And got one young officer to buy The Subjection of Women. There was a most gorgeous tea, which no-one hardly touched. Mrs Hill and I walked home together – got in about 6.30. Another evening of gabbling chat and to bed about 10 o’clock. She is very nice but so intellectual. I feel sorry for the child. A most terrific gale raged all night. I thought the house must be blown in.

Kate spent two weeks in Folkestone on that occasion, returned for another two in February 1912 and that autumn spent a further three weeks attempting to galvanise the Kent campaign into a semblance of life.

Saturday October 5th 1912 [Folkestone: 33 Coolinge Road]

In my morning of calls, I only found two people at home. At 12.30 I gave it up. I did feel depressed. More so when, having met Mrs Kenny at the Grand Hotel at 3.30, where she was attending a wedding reception of a Miss Cooper, and whose good-byes I just came in for, Mrs Kenny and I called together upon the manager’s wife, Madame Gelardi, and to my horror I found that her husband would not contemplate for a moment letting us have a Suffrage At Home in the reception room. Well that does put the lid on things.The time is slipping away here – the days fly, I love the place and am very comfortable in my rooms but I cannot seem to work here and I feel utterly miserable about it.

Kate’s mention – in the entry below – of ‘this split’ refers to the announcement Mrs Pankhurst had made on 17 October at an Albert Hall meeting that the Pethick-Lawrences were no longer involved with the WSPU. The Pethick-Lawrences’ departure had been unilateral. Lady Irving was the – long-estranged – widow of the actor, Sir Henry Irving

Tuesday October 22nd 1912 [Folkestone: 33 Coolinge Road]

As for the work I am doing here I am clean off it – I am doing nothing towards ‘Votes for Women’ – what do the people of Folkestone care and what is the good of trying to make them care? Propaganda may have had its uses in the past, it may still please some people, but I don’t want to go on talking about the Vote – I want to get it! And I am wondering more than ever what is the way to get it. This split, if split it is between the Pankhursts and Pethick-Lawrences is depressing, but I am not at all sure there it not more in it than meets the eye. Anyway here one feels so out of things – the Vote seems a very tiny speck in an ocean of talk and twaddle.

Back to tea and to write letters, then at 8 o’clock I tidied myself and went off to call on Lady Irving by appointment at 8.30. I was interested and so much enjoyed the interview, and she joined us as a member. I had been told of her powdered face, how, like the cat, she always walked alone, that all Folkestone hates her. I liked her immensely, she seems the only real person I have met, the only understanding person. I am told her temper is abnormal, that may be, she was sweet to me, and, after all, these sweet-tempered creatures can be temper trying enough for anything. That she and Henry Irving could not get on together I can quite understand. ‘No surrender’ is writ large in her composition – and after all why should the woman always give way. I imagine she had very strong views as to what was fitting for a wife and probably he did not live up to these. I did not stay long but we got a lot in the time and I think she liked me. How wonderfully young she is. Suffrage to her finger tips, and Suffrage before it was passably comfortable to be Suffrage.

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – e.crawford@sphere20.freeserve.co.uk (£14.99 +UK postage £3. Please ask for international postage cost), or from all good bookshops. In stock at London Review of Books Bookshop, Foyles, National Archives Bookshop.

Now Published: Campaigning For The Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary, Edited By Elizabeth Crawford

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on April 15, 2013

An extract:

‘Saturday June 14th 1913. [Kate is lodging in Baker Street, London] I had had a black coat and skirt sent there for Miss Davison’s funeral procession and the landlady had given me permission to change in her room. I tore into my black things then we tore off by tube to Piccadilly and had some lunch in Lyons. But the time was getting on – and the cortege was timed to start at 2 o’clock from Victoria.

We saw it splendidly at the start until we were driven away from our position and then could not see for the crowds and then we walked right down Buckingham Palace Rd and joined in the procession at the end. It was really most wonderful – the really organised part – groups of women in black with white lilies – in white and in purple – and lots of clergymen and special sort of pall bearers each side of the coffin.

She gave her life publicly to make known to the public the demand of Votes for Women – it was only fitting she should be honoured publicly by the comrades. It must have been most imposing.

The crowds were thinner in Piccadilly but the windows were filled but the people had all tramped north and later on the crowds were tremendous. The people who stood watching were mostly reverent and well behaved. We were with the rag tag and bobtail element but they were very earnest people. It was tiring. Sometimes we had long waits – sometimes the pace was tremendous. Most of the time we could hear a band playing the funeral march.

Just before Kings Cross we came across Miss Forsyth (a fellow worker for the New Constitutional Society) – some of the New Constitutional Society had been marching with the Tax Resisters. I had not seen them or should have joined in. I had a chat with her.

Near Kings Cross the procession lost all semblance of a procession – one crowded process – everyone was moving. We lost our banner – we all got separated and our idea was to get away from the huge crowd of unwashed unhealthy creatures pressing us on all sides. We went down the Tube way. But I did not feel like a Tube and went through to the other side finding ourselves in Kings Cross station.

Saying we wanted tea we went on the platform and there was the train – the special carriage for the coffin – and, finding a seat, sank down and we did not move until the train left. Lots of the processionists were in the train, which was taking the body to Northumberland for interrment – and another huge procession tomorrow. To think she had had to give her life because men will not listen to the claims of reason and of justice. I was so tired I felt completely done. We found our way to the refreshment room and there were several of the pall bearers having tea. ‘

Campaigning for the Vote tells, in her own words, the efforts of a working suffragist to instil in the men and women of England the necessity of ‘votes for women’ in the years before the First World War.

The detailed diary kept all her life by Kate Parry Frye (1878-1959) has been edited to cover 1911-1915, years she spent as a paid organiser for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. A biographical introduction positions Kate’s ‘suffrage years’ in the context of her long life., a knowledge of her background giving the reader a deeper appreciation of the way in which she undertook her work. Editorial comment adds further information about the people Kate meets and the situations in which she finds herself.

Campaigning for the Vote constitutes that near impossibility – completely new primary material on the ‘votes for women’ campaign, published for the first time 100 years after the events it records.

With Kate for company we experience the reality of the ‘votes for women’ campaign as, day after day, in London and in the provinces, she knocks on doors, arranges meetings, trembles on platforms, speaks from carts in market squares, village greens, and seaside piers, enduring indifference, incivility and even the threat of firecrackers under her skirt. Kate’s words bring to life the world of the itinerant organiser – a world of train journeys, of complicated luggage conveyance, of hotels – and hotel flirtations – , of boarding houses, of landladies, and of the ‘quaintness’ of fellow boarders.

This was not a way of life to which she was born, for her years as an organiser were played out against the catastrophic loss of family money and enforced departure from a much-loved home. Before 1911 Kate had had the luxury of giving her time as a volunteer to the suffrage cause; now she depended on it for her keep. No other diary gives such an extensive account of the working life of a suffragist, one who had an eye for the grand tableau – such as following Emily Wilding Davison’s cortége through the London streets – as well as the minutiae of producing an advertisement for a village meeting.

Moreover Kate Frye gives us the fullest account to date of the workings of the previously shadowy New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. She writes at length of her fellow workers, never refraining from discussing their egos and foibles. After the outbreak of war in August 1914 Kate continued to work for some time at the society’s headquarters, helping to organize its war effort, her diary entries allowing us to experience her reality of life in war-time London.

ITV has selected Kate Frye – to be portrayed by a leading young actress – as one of the main characters in a 2014 documentary series to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War.

See also ‘Kate Frye in “Spitalfields Life”‘ and ‘Kate Frye in “History Workshop Online”‘

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive. ISBN 978 1903427 75 0 Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – e.crawford@sphere20.freeserve.co.uk (£14.99 +UK postage £2.60. Please ask for international postage cost), or from all good bookshops. In stock at London Review Bookshop, Foyles, Daunt Books, Persephone Bookshop, Newham Bookshop and National Archives Bookshop.