Posts Tagged kate parry frye

Collecting Suffrage: Photographs Of The Equal Rights Rally, 3 July 1926

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on August 10, 2020

Two snapshots – taken at the rally by John Collins, Kate Frye’s husband.

Here’s an excerpt from Kate’s diary entry for the day, as reproduced in Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s suffrage diary (now out of print).

Saturday July 3rd 1926 [London: Flat C, 57 Leinster Square]

[After lunch] changed, off with J[ohn] – bus to Marble Arch and walked to Hyde Park Corner. Sat a little then saw the procession of women for Equal franchise rights and to the various meetings and groups. Heard Mrs Pankhurst and she was quite delightful. Also saw Ada Moore – getting very old. Saw Mrs Despard 82 and walked all the way. And the Actresses’ Franchise League.

The tiny snapshots show women and men walking into Hyde Park, with banners. If anyone else was taking photos that day, they do not seem to have made their way into public collections. Very good – very scarce. £20 the two together.

Do email me if you’re interested in buying these shadows of the past. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

SOLD

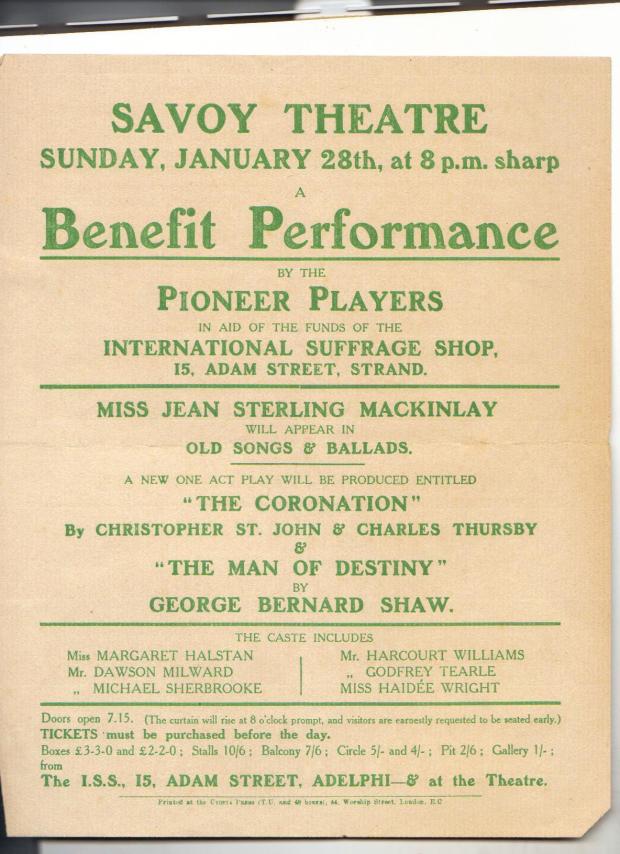

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Frye And The Problem Of The Diarist’s Multiple Roles

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 7, 2013

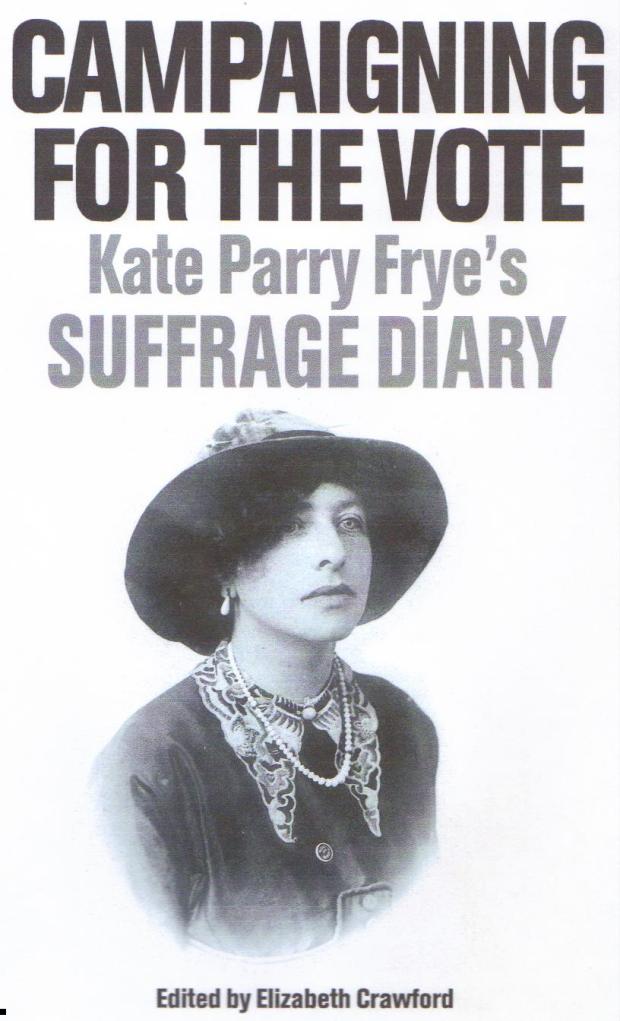

In the following article I discuss the ethics of ‘mining’ the diary that Kate Parry Frye kept for her entire lifetime in order to re-present her in one role only– as a suffragist. The piece is based on a paper I gave at the 2011 Women’s History Network Conference. Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary is published by Francis Boutle Publishers at £14.99

Kate Parry Frye[1] was a diarist. She was also a girl, a young woman, a middle-aged woman, an old woman, a daughter, a sister, a cousin, a niece, a fiancée, a wife, an actress, a suffragist, a playwright, an annuitant, a letter writer, a Liberal, a valetudinarian, a playgoer, and a shopper. She was a rail traveller, a bus traveller, a tube traveller, a reader, a flaneur, a friend, and a political canvasser. She was a diner – in her parents’ homes, in digs, in hotels, in restaurants, in cafés and later, of necessity, a diner of her self-cooked meals. She was an enthusiast for clothes, a keeper of accounts, a reader of palms, a dancer, a holidaymaker, a visitor to the dentist, to the doctor, an observer of the weather, a worker of toy theatres, a needleworker, an animal lover – indeed dog worshipper – a close observer of the First World War and then of the Second.

She was radio listener, a television viewer, a neighbour and, finally, a carer, recording in detail the effect on her husband of the remorseless onset of dementia and the disintegration of his body and mind. Every one of these roles is played out in minute detail in the diaries Kate Frye kept for 71 years, from 1887, when she was 8 years old, until October 1958, barely three months before her death in February 1959.[2]

Moreover, each role has its variations, depending on time and place. Thus, for example, as a middle-class daughter, Kate Frye played the pampered child, the indulged adolescent and, later, the resentful adult.

She was for many years supported financially and lived comfortably. In early womanhood she was afforded considerable freedom, her parents allowing her, indeed encouraging her, to train as an actress and to travel around Britain and Ireland with a repertory company. When that venture proved unprofitable she was able to return to life as a daughter-at-home, a role that appears to have combined the minimum of domestic chores with the maximum of freedom. Until December 1910 the family divided their time between two homes – a house, later a flat, in North Kensington and ‘The Plat’, a large detached, much-loved house on the river at Bourne End in Buckinghamshire.

But Kate Frye was also the daughter of a man whose business failed, whose lack of financial acumen she judged harshly, forcing as it did her mother, her sister and herself to leave their homes and sell all their possessions. Before 1910 there had been periodic indications of financial instability, when, for instance, ‘The Plat’ was let out for the summer, but Kate’s father failed to take his wife and daughters into his confidence, making the ultimate catastrophe all the more shocking. To Kate’s shame the family subsequently relied on the charity of her mother’s wealthy wine-merchant relations, the Gilbeys.[3] Her role in this performance might be studied, shedding as its does a clear light on the precarious reality of the long Edwardian summer. One year Kate could take for granted a life of boating and regattas, dressmakers, cooks and maids, the next she was living in dingy digs, attempting to raise money by hawking the family jewellery and old clothes around shops, while wondering if her relations had remembered to send the remittance and what she would do if they forgot..

Or perhaps one could look through Kate Frye’s eyes at the reality of working the towns of Edwardian England, Scotland and Ireland as an actress.

For instance, between September and December 1903 she was a member of a Gatti and Frohman touring production of J.M. Barrie’s Quality Street and writes in considerable detail of company train travel, theatrical lodgings and the other members of the cast, among who was a young May Whitty. Kate was paid £2 a week and includes in the diary some weekly accounts, which could be studied in conjunction with the management’s financial accounts of the tour.[4] Or her diary could be used to give an insight into the issue of class and gender in the Edwardian theatre; Kate’s experience does not indicate that family and friends felt that her new role was in any way either imprudent or declassé.[5] Or her diary might be used to research the behind-the scenes world of post-1918 theatre, as Kate reports on her husband’s attempt to earn a precarious living as actor and stage manager.[6] Kate’s involvement with theatre saw her performing on both sides of the stage – in her role as an actress and, in the auditorium, as a spectator – and her diary might also be used to study of the habits of playgoers over the decades, recording as it does her comments on the vast number of performances she attended. On occasion she thought nothing of seeing two plays in one day.

Kate kept a separate record of all the plays she saw – including Elizabeth Robins’ ‘Votes for Women!’

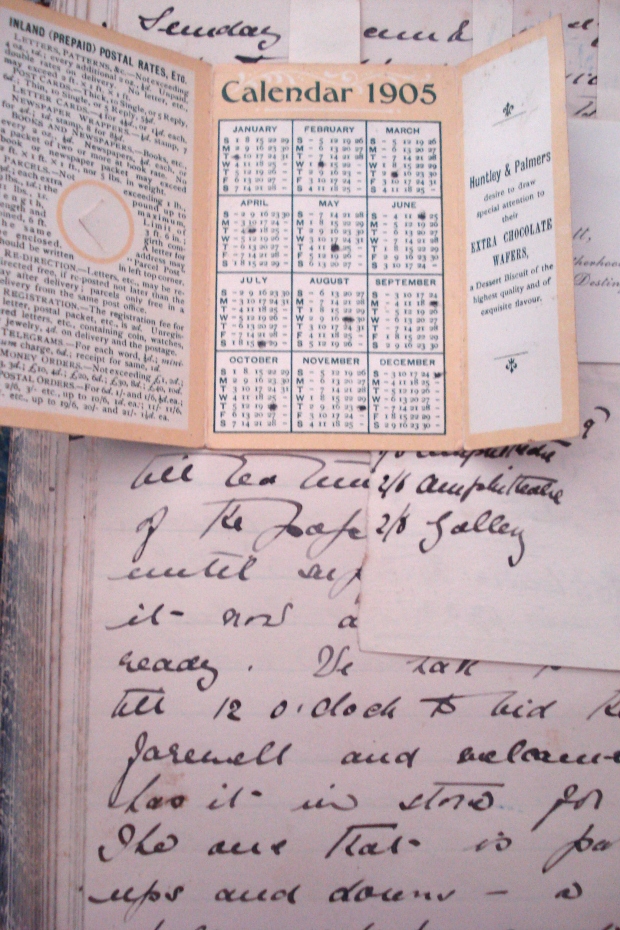

Or perhaps one could use her diary to study the nature of ill-health, real or perceived. Menstrual pain – ‘the rat pain’ – lurks behind some of Kate’s continuous complaints of ‘seediness’ and included in some of the diaries are small yearly calendars with the date of each menstrual period marked in pencil.

But the feeling of ill-health suffered by Kate, by her elder sister, Agnes,[7] and their mother was due to more than menstruation. For weeks at a time, year after year, one or the other, or all three, are confined to their beds. The doctor calls – and is paid – medications are prescribed and taken. For some of the time ‘seediness’ is endured and Kate, at least, gets on with things. It is noticeable that when she has an active life to lead, whether on tour as an actress or as a suffrage organiser, she makes many fewer complaints of ill-health. It is difficult to avoid the thought that some, at least, of the malaise was due to depression occasioned by lack of occupation. Kate did, after all, continue fit and healthy until she was 80. The diary could be read and edited to bring this aspect of her life to the fore, studying the links, in the first 50 years of the 20th century, between status, expectation and occupation – or lack of it – and mental and physical wellbeing Certainly Kate’s sister, who never worked and appears to have had few interests, seems to have given up on life, spending much of her later years in bed and drifting into death. However, although these aspects of Kate Frye’s life are intriguing, it is for her involvement with the Edwardian suffrage movement that she is now likely to be remembered. For Kate Frye’s diaries have been directed, by chance, towards an editor whose research interests centre on suffrage.

Kate was what one student of diary writing terms a ‘chronicler’, that is her diary was a ‘carrier of the private, the everyday, the intriguing, the sordid, the sublime, the boring – in short a chronicle of everything’ and in its extent is not a little daunting.[8] But, reading the volumes covering the years prior to the First World War, one quickly realises that involvement in one of the major campaigns of the day provided Kate’s life – and her diary – with a focus. For the Frye family’s descent into near, if genteel, destitution coincided with the growth of the suffrage movement, which subsequently provided Kate with employment. Although she was untrained for any career other than acting, which she had found, in fact, did not pay, work of a political nature was not outside her sphere of knowledge, for one of her earlier roles had been that of the daughter of an MP. Kate’s father, Frederick Frye, had been the Liberal member for North Kensington from 1892 to 1895 and an interest in politics was taken for granted within the family. Over the years Kate had helped her mother with the regular ‘At Homes’ held for the Liberal ladies of North Kensington and had accompanied her father to many a political meeting.

The diary entries trace her growing involvement in the suffrage campaign, from participation in the first NUWSS ‘Mud March’ in early 1907, through her performance as a palm reader at numerous fund-raising suffrage bazaars and dances, attendance at meetings of the Actresses’ Franchise League, marching in all the main spectacular processions, stewarding at meetings, bearing witness to the ‘Black Friday’ police brutality in Parliament Square on 18 November 1910, to her employment, from early 1911 until mid-1915, as a paid organiser for the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage. The diary, as edited as Campaigning for the Vote, highlighting the detail Kate provides of daily life as a suffragist and illustrated with the wealth of suffrage ephemera with which she embellished the original, is an interesting addition to published source material.

But what are the ethics of spotlighting this one role – or any role – from a lifetime performance? Kate’s diary seems to lend itself quite naturally to a style of editing that sets her entries, replete with delightfully quotidian suffrage detail, within a linking narrative, explaining the greater campaign and providing information on people she meets in the course of her days. But, increasingly uneasy, the editor of Kate Frye’s diary felt it necessary to take soundings from commentators on diary writing in order to discover whether the perceived problem, that of highlighting only one of the diarist’s multiple roles – one of her many selves, is one that others have resolved.

Robert Fothergill’s Private Chronicles, published 35 years ago, is generally considered the earliest academic work to have made a serious study of diary-writing.[9] In his study Fothergill considered the diaries both of men and of women but since then much of the attention the genre has received has concentrated on diary writing by women. For in the 1980s and 1990s, with the growing interest in women’s history, academics such as Margo Culley, Cheryl Cline, Harriet Blodgett, Suzanne Bunkers and Cynthia Huff saw women’s diaries as an exciting new source through which to re-examine and re-envisage women’s lives.[10] As Bunkers and Huff wrote, ‘Within the academy the diary has historically been considered primarily as a document to be mined for information about the writer’s life and times – now the diary is recognized as a far richer lode. Its status as a research tool for historians, a therapeutic instrument for psychologists, a repository of information about social structures and relationships for sociologists, and a form of literature and composition for rhetoricians and literary scholars makes the diary a logical choice for interdisciplinary study.’[11] These writers use metaphors such as ‘weaving’, ‘quilting’, ‘braiding’ and ‘invisible mending’ to describe the way in which a woman fashions her diary, a diary of dailiness rather than of great moments. But that ‘weaving’ or ‘quilting’ or ‘braiding’ lies at the heart of the problem. Is it legitimate to unravel this self-construction and fashion it into something else?

That question might be answered quite simply by a judgment made in 1923 by Sir Arthur Ponsonby and much quoted, even by the American women historians of the 1980s. For in English Diaries, Ponsonby was adamant: ‘No editor can be trusted not to spoil a diary.’[12] For his part, Robert Fothergill stated that the only respectable motive behind the amputation of a diary was the desire to make it readable – ‘commonly the abridgement or distillation of an unwieldy original, through the elimination of whatever was considered stodgy, pedestrian or repetitious’.[13] But such an ‘amputation’ is not unproblematic, for what might be considered stodgy and pedestrian to one reader, or in one decade, might be lively and interesting to the next. To anyone interested in the daily life of a suffragist, even the repetitions in Kate Frye’s daily life are revealing. Cheryl Cline elaborated Fothergill’s point, writing, ‘The most sensitive and careful editors, in cutting what they may feel unimportant, irrelevant, repetitious or even “too personal”, walk a very fine line. They may end up, for all their good intentions, ruining the work. Many editors have been neither sensitive nor careful. Editors have cut manuscripts they felt were too long, padded those they thought too short; re-arranged material to suit themselves; bowdlerized writings which revealed the less-than-perfect character of their authors. Too often, they have destroyed the originals once the edited version was published’.[14] So reservations about editing Kate Frye’s lifetime performance to refashion it as a ‘suffrage diary’ are, perhaps, not unjustified, although Kate Frye’s published diary will be neither ‘padded out’, or ‘bowdlerized’, nor will the original be ‘destroyed’. However, the charge of ‘re-arrang[ing] material’ is, perhaps, not inappropriate. It is not that the published entries will have been re-arranged, rather they will have been accorded a prominence they did not have in the original.

It is worth remarking that much of the academic literature on diary writing concentrates on the published diary.[15] There appears to be little recent consideration of the ethics of, as Bunkers and Huff put it, ‘mining’ a manuscript diary for the light it throws on particular aspects of the past, other than the difficulty this creates for those critiquing diary writing per se. Indeed, these authors appear to suggest that it was only in the past that a diary would be treated in this way. Fothergill touched on this point, condemning most severely ‘the ravages of editors, committed in, amongst other things, the name of thematic unity, writing that, from the point of view of his study of diaries, ‘A fatally damaging editorial approach is the subordination of a diary’s general interest to a specialist one, retaining only what is of use to the political or religious historian, for example.’[16] However Cheryl Cline has taken a more tolerant attitude to this aspect of diary editing, commenting ‘The urge to make a “good story” out of a diary that seems rambling and disjointed…is the motive which guides many an editor’s blue-pencil. While many diaries..are written around a theme .. or an event .., most private writings are disjointed and far-ranging. In this case material may be extracted from them and shaped into a more cohesive narrative.’[17] She then cites, as a well-known example of editing for story, A Writer’s Diary, compiled from Virginia Woolf’s diary by Leonard Woolf.[18] Kate Frye’s diary, edited to tell her suffrage story, might, therefore, be said to be keeping exalted company.[19] However it is certainly true that since the middle of the 20th century, the move in diary editing has been towards the unabridged text, complete with full scholarly apparatus. But Kate Frye would never be given that kind of treatment. So is it better to give a wider audience a ‘ravaged’ text – or to leave it, unpublished, in its wholeness on the archive shelf? An argument for leaving it untouched might well be made by the academics who have stressed the importance of the diary as a complete self-construct, a form of autobiography or life writing.[20] The author has considerable sympathy with this viewpoint, while recognising the specific interest to students of women’s suffrage in retelling the story of Kate’s suffrage years.

But perhaps, if theory cannot provide a clear answer, we should look for guidance to the diarist herself. What would Kate Frye have liked done with her text? Although she has been dead for 50 years that text is still alive with her personality and it is not inconceivable that someone who put so much of herself onto the page, developing her writing skill as she shaped her life, would have been happy to have known that she would one day reach out to a wider audience.

In this context it is worth considering for whom Kate Parry Frye had been performing. Most certainly in her diary she acted out her days for herself. From her very early years the diaries had become an essential part of her life. On occasion she discusses whether to bring her diary writing to an end, but always decides to carry on. Until mid-1916, utilising the format that Cynthia Huff describes as ‘self-determined,’ Kate wrote her entries in a large ledger-type book, embellishing them with the addition of relevant ephemera.[21] When, on 16 November 1913, on reaching the end of yet another of these books, she wrote ‘And so I have come to the end of this volume with no book to go on with though I have written to Whiteleys.[22] It would be more sensible to leave off writing a diary – at any rate such an extensive one – but more lonely’. But she did acquire another volume from Whiteleys, although that was to be the last of this kind and she afterwards continued her record in purpose-made diaries, adhering, more or less, to the space allocated for each day and no longer inserting additional material..

So that is one explanation as to why Kate kept her diary; it was her daily companion. In it she depicts herself as slightly aloof from her parents, sister and husband, her abilities unappreciated. As Fothergill has observed, ‘the function of the diary is to provide for the valuation of [self] which circumstances conspire to thwart.’[23] Financial circumstances certainly thwarted Kate’s ability to maintain the class position that for some years she had enjoyed, but in her diary she could continue to present herself as an aspiring member of the upper-middle middle class, although, after 1910, always conscious of the financial chasm that existed between this idea of herself and the reality. On March 17th 1913, when meeting her Kensington contemporaries, she notes: ‘They all seemed so smart and so well dressed and so of a different life – the life really that we have left behind. Oh what a difference money makes.’ Lack of money is a recurrent theme, although in her entry for 22 December 1913 she does try to overcome her regrets, writing, ‘I always feel given nice clothes … I could look nice and attractive. I hate being shabby. It is bad enough to grow old, but to grow dowdy with it, but what can one do without money and lots of it. I do seem to grumble. I seem to forget I am aiming for “goodness” in an advanced and suffrage meaning, and that really any other state is very petty.’ It was not that she struck extravagant poses in her diary, rather that there she felt that there her days were being re-enacted in front of an appreciative audience – herself.

Kate seldom dwells on the act of diary writing, but on Sunday 8 February 1914 was prompted to record:

‘I am reading ‘The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff’. It is too absolutely interesting for words – and yet all so natural….it isn’t far off me in the inmost soul. Only in performance she was a genius – she could do – I can only dream that I could and do – accomplish. It made me want to read my old Journals but how tame after Marie’s. I was always for putting time and place and leaving out the really interesting bits in consequence – though I sometimes think I catch atmosphere. That is the disadvantages of writing a diary instead of a Journal – one only ought to write when one is inspired and at the moment the feeling or idea strikes one – but with a diary the date and correctness is the thing.’[24]

Perhaps it is fortunate for us the Kate did not write what she terms a ‘Journal’; it is the ‘putting time and place’ that makes Kate’s diary so interesting.[25] We can sit with her on the tube or bus, travelling around London; we can reconstruct the route taking her from Notting Hill Gate to the Criterion Restaurant in Piccadilly for a meeting of the Actresses’ Franchise League – and then eavesdrop on the proceedings; we can go with her to Covent Garden to see the Russian Ballet – ‘as for M Nijinsky, well, words fail me’;[26] we can travel with her around the country roads of Norfolk, searching out suffrage sympathisers; and accompany her as she organises the transport of her boxes, a complicated business, to and from stations and ‘digs’ in the small towns of east and southern England.

For Kate Frye’s diary keeping makes no distinction between the daily chores – brushing her dog, having lunch, changing her books at Smith’s – and life-changing events. Even so, like all diarists, it is clear that she edited her day and, unsurprisingly, for her diaries had no locks, did not make explicit the details of everything that happened to her. For instance, it was only the reading of an entry in a post-Second World War diary that gave a clue to what lay behind her long association with – and eventual marriage to – John Collins, a fellow actor in the 1903 touring production of Quality Street, a relationship that, as presented in Kate’s words, seems rather puzzling. That post-war entry referred to the one for 20 September 1904, the day that Kate finally agreed to marry John. The entry itself is, naturally, of interest because she is writing of the day of her engagement but, when read in context, is constructed – or self-edited – so as not to include anything particularly revealing, merely that, after some, perhaps rather melodramatic, hesitation, Kate had finally acquiesced to John’s repeated offer of marriage. However, on re-reading the entry in the light of the later comment, a rather different story emerges. Kate’s words – ‘..I had to promise, it is the only right thing left to do …I couldn’t marry anyone else now, as he says. I have burnt my boats and no one must ever know that my real self is hesitating’ – appeared to be those of a woman who had realised that she had to make a decision, that she could no longer keep the man hanging on. But, alerted by the entry written nearly 50 years later, a re-reading reveals a rather different story. For, it transpires Kate had acted in such a way that ensured that, this time, she had to agree to marry John. It is hardly worth speculating on what actually had occurred, although in this entry Kate does write of passion and desire. In fact his lack of money, coupled with her lack of inclination, meant that it was a further 11 years before Kate and John married. Although she often debates with herself as to whether she can continue with the engagement, Kate feels unable to escape what she sees as her obligation. The story of that day in Croydon digs – with the landlady out shopping – is only one, albeit major, episode where the diarist, while ostensibly being frank, has not made all explicit.

There are doubtless very many other such occasions on which the doings of the self as portrayed in Kate’s diary do not reflect exactly the experience of the self that enacted them, the self of the diary having been refashioned by the diarist’s pen. For Kate Frye recognised her diary’s usefulness in providing her with the daily discipline of putting words on paper. Her diary is written in direct, colloquial prose. Her writing is fluent and she makes virtually no corrections. As we have seen, she was interested in ‘catching atmosphere’ and, although she never intended her diary for publication, she did aspire to literary success. Over many years she mentions time spent on ‘writing’ and a quantity of her manuscripts and typescripts, together with the rejection letters from agents and publishers, survive. Unsurprisingly, for one so enamoured of the theatre, these works are all plays, but only a one, co-written with John Collins, was ever published.[27]

Regretting as she did her lack of literary success, it is difficult to believe that she would be averse to seeing her words in print now.

Recognising the affection Kate felt for her diary and the time and care she had spent on shaping it, it is worth considering what she had thought might happen to it after her death. In fact her will reveals that the diaries were in effect her main bequest. She left the many volumes, together with the lead-lined bookcase in which they were kept, itself an indication of the concern she felt for their well-being, to the son of one of her cousins. That cousin, long dead, had been the only one of her relations to have had similar literary aspirations, albeit rather greater success. For, Abbie Frye was a prolific Edwardian novelist who wrote under the name ‘L. Parry Truscott’.[28] Kate had clearly wanted the diaries preserved and had not been worried at the thought of their being read by a member of the younger generation – and, by inference, a later general public. But would she have objected to being presented to the general public only in her role as a suffragist – for that is in effect how she is now re-created?

So let us now view the problem from the other side and consider the contribution that Kate Frye’s diary may make to our understanding of the suffrage movement and of the lives lived by its members. How does Kate’s diary stand among other diaries dealing with the suffrage movement? What makes it worth the trouble of editing and publishing? The main difference between the diary of Kate Frye and most others recording suffrage involvement that survive in the public domain is that the latter were written primarily because that involvement represented a singular experience, a highpoint in the diarist’s life. Thus, for instance, the militant campaign is well represented by diaries kept by imprisoned suffragettes, recording the horrors of forcible feeding.[29] For the constitutionalists, two diaries kept by Margery Lees have survived. Leader of the Oldham NUWSS society, she has recorded in one the work of the society and, in the other, gives an account of her participation in a great NUWSS event, the 1913 suffrage pilgrimage.[30]

Apart from that of Kate Frye, only a handful of other diaries with suffrage-related daily entries are known. Those of the delightfully Pooterish Blathwayts of Batheaston, father, mother and daughter, have proved an excellent source for researchers of WSPU personalities and of the militant campaign in Bath[31] and that of Dr Alice Ker provides short factual notes on the suffrage scene in Birkenhead and Liverpool.[32] The diary of Eunice Murray, a prominent Scottish member of the Women’s Freedom League, is in some ways comparable to that of Kate Frye, although the former’s comments on the suffrage campaign are more measured, while her actual accounts are less detailed.[33] Like Kate, Eunice Murray spoke at suffrage meetings but was not required to organise them and was certainly less concerned with ‘catching the atmosphere’ when writing up her diary entries. The diaries of the actress and novelist Elizabeth Robins (held in the Fales Library, New York) record her involvement with the English suffragette movement but, again, although she contributed as a speaker, she was not working at the suffrage ‘coal face’, as it were. None of these diaries, suffragist or suffragette, has yet been published. Excerpts from the diaries of Ruth Slate and Eva Slawson make clear their interest in the Cause and, interwoven with material from their letters, have been published, but within the overall narrative of their lives and concerns suffrage plays only a relatively minor part.[34]

Kate’s diary is valuable because it records her continuous involvement as a foot soldier in the suffrage campaign. She is writing without the benefit of hindsight, recording the inconsequential details of, say, finding a chairman for a suffrage meeting in Maldon or dealing with an imperious speaker in Dover, as well as the rather more momentous suffrage occasions, such as waiting on the platform at King’s Cross station as the train carrying Emily Wilding Davison’s coffin is about to leave for Morpeth. We can trace day by day, week by week, Kate’s growing participation in the movement, reflecting as it does both the increasing publicity given to and acceptance of the suffrage campaign and the decline in her family’s fortunes.

In 1913 Kate was campaigning for the New Constitutional Society in Whitechapel, distributing NCS leaflets translated into Yiddish

Although we cannot say that she became an increasingly militant (although never actively militant)[35] supporter because she regretted her lack of education, in the very first entry in which she refers to suffrage, on 3 December 1906, she writes: ‘I really do feel a great belief in the need of the Vote for Women – if only as a means of Education. I feel my prayer for Women in the words of George Meredith: “More brains, Oh Lord, more brains” ‘[36] – or, again, in 1914, ‘Neither do I understand why I was born if I wasn’t to be educated.’ Kate’s education had been that considered suitable for her gender and class. She did not attend school, but until she was 16 was visited by a ‘daily governess’, although visits were not invariably daily. After that she received somewhat erratic tuition from teachers of French and music. Nor can we say she became a suffragist because she lacked economic power. But she was certainly aware that those two factors – a lack of education and a lack of funds – made life as a woman without the shelter of family money, or the ability to earn her own, very difficult.

Like so many other women at that time, Kate Frye saw the acquisition of the vote as one step towards autonomy. It is our luck that for a few years she attempted to solve her economic problem by propounding the political solution, that is, she earned a living, of sorts, by becoming a suffrage organiser. It is extra fortunate that she did so for a society, the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage, about which very little has hitherto been known. In fact Kate Frye’s diary contains more information about the NCSWS and more of the society’s ephemera than exists anywhere else.

Her elaboration of diary entries by the addition of leaflets advertising the suffrage meetings she attended, even on occasion leaflets she herself had arranged to have printed, and for the processions in which she took part, demonstrates how prominently the campaign figured in her life. Virtually no other ephemeral material is included during this period.

We need only look to the diary for the answer to the question as to whether Kate Frye would object to being remembered as a suffragist. For on ‘Sunday 10 February 1918’ she wrote, ‘One of my afternoon letters was to Gladys Simmons[37] in commemoration of the passing of the Franchise Bill. Haven’t had a single letter from anyone concerning it – I said I wouldn’t but it seems very strange – that someone hasn’t thought of me in connection with the work.’ Now that her suffrage diary is published, at last Kate Frye will ‘be thought of in connection with the work’ and be recognised as a suffragist.[38] However, the very act of publication highlights just this one of her many roles. Out of the multiplicity of Kate Frye’s self-constructions, it is the ‘self’ of her suffrage years that emerges. The reader will have to accept that ‘mining’ a diary in order to view an historical episode from a fresh angle may come at the expense of maintaining the integrity of the diarist’s conception of ‘self’.

Kate’s diary entry for 21 May 1914 in which she records witnessing the WSPU demonstration in front of Buckingham Palace

[1] Katharine Parry Frye (1878-1959), daughter of Frederick and Jane Kezia Frye. Frederick Frye was a director of a chain of licensed grocery shops, Leverett and Frye, a firm financed by the wine merchants W.& A.Gilbey, as a useful outlet for their wines. When Frederick Frye became an M.P., Gilbey’s took over the running of the business. The Irish branch still operates. Frederick’s father had been a ‘professor of music’ and for 64 years organist at Saffron Walden parish church. Jane Frye’s father was a Winchester grocer. In 1915 Kate married John R. Collins.

[2] In August 2010 correspondence on Guardian Online, which included contributions from members of the Women’s History Network, demonstrated that it is by no means unusual for contemporary women to keep daily diaries over decades of their lives..

[3] Kate’s Aunt Agnes (1834-1920, née Crosbie), her mother’s sister, was the widow of Alfred Gilbey (d. 1879). For details of the Gilbeys of Wooburn House, Wooburn, Buckinghamshire see B. B. Wheals (1983) Theirs were but human hearts: a local history of three Thameside parishes (Bourne End: H.S. Publishing). From their relatively humble origins the brothers Walter and Alfred Gilbey grew wealthy as they developed England’s largest wine merchant business, W. & A. Gilbey.

[4] ‘Accounts and Legal’, Quality Street tour accounts (Theatre Museum), cited in Tracy C. Davis (2000) The Economics of the British Stage 1800-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) p.217.

[5] For a discussion of the entrance of middle-class women into the acting profession see Tracy C. Davis (1991) Actresses as Working Women (London: Routledge) pp. 13-16.

[6] In the 1920s and 1930s Kate often joined her husband on tour. For instance, over many years she spent some time each year at Stratford-on-Avon, where her husband was stage manager for productions at the old Memorial Theatre.

[7] Agnes Frye (1874-1937)

[8] See T. Mallon (1995) A Book of One’s Own: people and their diaries (St Paul, Minn: Hungry Mind Press) p. 1.

[9] Robert A. Fothergill (1974) Private Chronicles: a study of English diaries (London: OUP).

[10] See Jane DuPree Begos (1977) Annotated Bibliography of Published Women’s Diaries (issued by the author); Margo Culley (Ed) (1985) A Day at a Time: the diary literature of American women from 1764 to the present day (Old Westbury NY: Feminist Press); Harriet Blodgett (1989) Centuries of Female Day: Englishwomen’s Private Diaries (New Brunswick, London: Rutgers University Press); Cheryl Cline (1989) Women’s Diaries, Journals and Letters: an annotated bibliography (New York and London: Garland Publishing); Harriet Blodgett (Ed.) (1992) The Englishwoman’s Diary (London: Fourth Estate); Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia A. Huff (1996) Inscribing the Daily: critical essays on women’s diaries (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press) Suzanne L. Bunkers (2001) Diaries of Girls and Women: a midwestern American sampler (London, University of Wisconsin Press).

[11] Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia Huff ‘Issues in Studying Women’s Diaries: a theoretical and critical introduction’, in Bunkers and Huff (Eds) Inscribing the Daily, p.1

[12] Sir Arthur Ponsonby (1923) English Diaries (London:Methuen & Co), p. 5.

[13] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p. 5

[14] Cline, Women’s Diaries, p xxvii-xxviii.

[15] Exceptions include Bunkers, Diaries of Girls and Women. See also Cynthia Huff (1985) British Women’s Diaries: a descriptive bibliography of selected 19th-century women’s manuscript diaries (New York: AMS Press).

[16] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p. 5.

[17] Cline, Women’s Diaries, p. xxviii.

[18] L. Woolf (Ed) (1953) A Writer’s Diary. Being extracts from the diary of Virginia Woolf (London, Hogarth Press).

[19] Although, after Leonard Woolf’s ‘dismembering’, the diaries were reconstructed, in five volumes, edited by Anne Olivier Bell.

[20] For instance, Martin Hewitt (2006) Diary, Autobiography and the Practice of Life History in David Amigoni (Ed) Life Writing and Victorian Culture (Aldershot: Ashgate).

[21] Huff, British Women’s Diaries, p xiv.

[22] Whiteleys was a large department store, which, when Kate wrote this 1913 entry, was in Queensway. The store’s owner, William Whiteley, ‘the Universal Provider’, had been a close friend of the Frye family and his murder and subsequent trial are recorded in detail in Kate’s 1907 diary.

[23] Fothergill, Private Chronicles, p.82.

[24] .Marie Bashkirtseff, a young Frenchwoman, filled 85 notebooks with her journal, which was edited for publication after her death in 1884. An English edition, Mathilde Blind (Ed. and Trans) 1890, The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff (London: Cassell) 2 volumes. Philippe Lejeune has described the Journal as foreshadowing ‘a line of diaries where introspection, active contestation of the condition of women, and interest in writing stand out as defining features’, see Philippe Lejeune The “Journal de jeune fille” in Nineteenth Century France in Bunkers and Huff, Inscribing the Daily, p119.

[25] Some attention has been paid to this distinction by scholars of diary writing. Suzanne Bunkers, after initially believing that what distinguishes a journal from a diary is that the diary is ‘a form of recording events, and the journal is a form of introspection, reflection, and the expression of feeling’, comes to the conclusion that the distinction is untenable, see S. Bunkers, Diaries of Girls and Women, p 12.

[26] Diary entry for 9 July 1912.

[27] Katharine Parry and John R. Collins (1921) Cease Fire!: a play in one act (London: French’s Acting Editions).

[28] Gertrude Abbie Frye (always known as Abbie), later Mrs Basil Hargrave (1871-1936). The works of ‘L. Parry Truscott’ were mistakenly attributed to Katharine Edith Spicer-Jay in Halkett (1926) Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous English Literature, (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd), Vol 1. By 1926 ‘L. Parry Truscott’’s star had waned and Abbie, by now a widow, was vitually penniless. A considerable amount of information about the interesting life of Abbie Frye can be gleaned from Kate Frye’s diary.

[29] See the manuscript prison diaries of Mary Anne Rawle, Elsie Duval and Katie Gliddon (Women’s Library); the manuscript prison diaries of Olive Walton and Florence Haig (Museum of London); and the manuscript prison diary of Olive Wharry (British Library); The manuscript prison diary of Anne Cobden Sanderson (London School of Economics) has been edited by Anthony Howe but is, as yet, unpublished.

[30] Both Margery Lees’s diaries are held by the Women’s Library.

[31] The Blathwayt diaries are held in the Gloucestershire Record Office. See June Hannam ‘Suffragettes are Splendid for Any Work’: the Blathwayt Diaries as a Source of Suffrage History in Clare Eustance, Joan Ryan and Laura Ugolini (Eds.) (2000) A Suffrage Reader: charting directions in British Suffrage History (London: Leicester University Press).

[32] Dr Alice Ker’s diaries are held in a private collection.

[33] The manuscript of Eunice Murray’s diary are held at the Women’s Library, together with a bound copy of the Diary of Eunice Guthrie Murray, transcribed by Frances Sylvia Martin.

[34] T. Thompson (Ed.) (1987) Dear Girl: the diaries and letters of two working women (1897-1917) (London: Women’s Press).

[35] Kate Frye joined the WSPU in November 1910, after witnessing the ‘Black Friday’ demonstration, but was soon appointed as a paid organiser for the newly-formed New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage.

[36] The quotation is taken from Modern Love by George Meredith, first published in 1862.

[37] As Gladys Wright, she had been a very old Kensington friend of Kate Frye and hon. Sec. of the NCSWS.

[38] Campaigning for the Vote: The Suffrage Diary of Kate Parry Frye, is published by Francis Boutle

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: Spring 1908 – Suffrage Hope – WSPU in Albert Hall ‘a little too theatrical but very wonderful’

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on September 26, 2012

Another extract from Kate Frye’s manuscript diary. An edited edition of later entries (from 1911), recording her work as a suffrage organiser, is published as Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s suffrage diary.

Kate’s MP, Henry Yorke Stanger, was the promoter of the current Enfranchisement Bill – the latest in the long line that stretched back through the latter half of the 19th century. Despite, as Kate describes, the bill passing its second reading, the government eventually refused to grant facilities to further the debate. However, that blow was yet to come as Kate records in these entries details of the suffrage meetings she attended in February and March 1908. She had the knack of always being present on the great occasions – and on 19 March was in the Albert Hall to witness the rousing – and profitable – reception given to Mrs Pankhurst on her release from prison.

Dramatis personae:

Miss Harriet Cockle, was 37 years old, an Australian woman of independent means, lving at 34 de Vere gardens, Kensington.

Mrs Philip Snowden – Ethel Snowden (1880-1951) wife of the ILP politician, Philip Snowden.

Mrs Clara Rackham (1875-1966) was regarded as on the the NUWSS’s best speakers. In 1910 she became president of the NUWSS’s Eastern Federation, was founder of the Cambridge branch of the Women’s Co-operative Guild, and was sister-in-law to Arthur Rackham, the book illustrator.

Margery Corbett (1882-1981- later Dame Margery Corbett-Ashby) was the daughter of a Liberal MP. At this time she was secretary of the NUWSS.

Mrs Fanny Haddelsey,wife of a solicitor, lived at 30 St James’s Square, Holland Park.

Mrs Stanbury had been an organiser for NUWSS as far back as 1890s.

Tuesday February 25th 1908 [London-25 Arundel Gardens]

We got home at 5.15 and had tea. Then I did my hair and tidied myself and Agnes and I ate hot fish at 6.30 and left soon after in a downpour of rain for the Kensington Town Hall – we did get wet walking to the bus and afterwards. We got there at 7 o’clock to steward – the doors were opening at 7.30 and the meeting started at 8.15. I was stewarding in the hall downstairs and missed my bag – purse with 6/- and latch Key etc – very early in the evening which rather spoilt the evening for me as I felt sure it had been stolen. It was a South Kensington Committee of the London Society for Woman’s Suffrage and we were stewarding for Miss Cockle. It was a good meeting but not crowded but, then, what a night. Miss Bertha Mason in the Chair. The speech of the evening was Mrs Philip Snowdon, who was great, and Mrs Rackham, who spoke well. The men did not do after them and poor Mr Stanger seemed quite worn out and quoted so much poetry he made me laugh. Daddie had honoured us with his presence for a little time and had sat on the platform – so I feel he has quite committed himself now and will have no right to go back on us. We were not in till 12.20 and then sat some time over our supper.

Wednesday February 26th 1908

Before I was up in the morning Mother came up in my room with my bag and purse and all quite safe. It had been found and the Hall Door Keeper had brought it. I was glad because of the Latch Key. Daddie generously had paid me the 6/- which I was able to return.

Friday February 28th 1908

Mr Stanger’s Woman’s Suffrage Bill has passed the second reading. I had to wait to see the Standard before going to my [cooking] class. That is very exciting and wonderful – but of course we have got this far already in past history. Oh! I would have liked to have been there.

MargWednesday March 11th 1908

To 25 Victoria Street and went to the 1st Speakers Class of the N.[ational] S.[ociety] of W.[omen’s] S.[uffrage]. I was very late getting there and there was no one I knew so I did not take any part in the proceedings and felt very frightened. But Alexandra Wright came in at the end and I spoke to Miss Margery Corbett and our instructoress, Mrs Brownlow. And then I came home with Alexandra from St James’s Park station to Notting Hilll Gate.

Thursday March 12th 1908

Mother went to a Lecture for the NKWLA [North Kensington Women’s Liberal Association] at the Club and Agnes and I started at 8 o’clock and walked to Mrs Haddesley [sic] for a drawing-room Suffrage Meeting at 8.30. Agnes and I stewarded and made ourselves generally useful. The Miss Porters were there and a girl who I saw at the Speakers’ Class on Wednesday. Alexandra was in the Chair and spoke beautifully – really she did. And Mrs Stanbury spoke. Mrs Corbett and Mrs George – all very good speakers. Mrs Stanbury was really great and there were a lot of questions and a lot of argument after, which made it exciting. It was a packed meeting but some of the people were stodgy. Miss Meade was there with a friend – her first appearance at anything of the kind she told us and she said it was all too much for her to take in all at once. The “class” girl walked with us to her home in HollandPark and we walked on home were not in till 11.45. I was awfully tired and glad of some supper and to get to bed.

Mrs Pankhurst had been arrested on 13 February as she led a deputation from the ‘Women’s Parliament’ in Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. She was released from her subsequent imprisonment on 19 March, going straight to the Albert Hall where the audience waiting to greet her donated £7000 to WSPU funds. Kate was there.

Thursday March 19th 1908

I had a letter in the morning from Miss Madge Porter offering me a seat at the Albert Hall for the evening and of course I was delighted….just before 7 o’clock I started for the Albert Hall. Walked to Notting Hill gate then took a bus. The meeting was not till 8 o’clock but Miss Porter had told me to be there by 7 o’clock. We had seats in the Balcony and it was a great strain to hear the speakers. It was a meeting of the National Women’s Social and Political Union – and Mrs Pankhurst, newly released from Prison with the other six was there, and she filled the chair that we had thought to see empty. It was an exciting meeting. The speakers were Miss Christabel Pankhurst, Mrs Pethick Lawrence, Miss Annie Kenney, Mrs Martel and the huge sums of money they collected. It was like magic the way it flowed in. It was all just a little too theatrical but very wonderful. Miss Annie Kenney interested me the most – she seems so “inspired” quite a second Joan of Arc. I was very pleased not to be missing so wonderful an evening and I think it very nice of Miss Porter to have thought of me. She is quite a nice girl of the modern but “girlie” sort – a Cheltenham girl and quite clever – but very like a lot of other girls. Coming out we met, strangely enough, Mrs Wright and Alexandra (Gladys was speaking at Peckham) and after saying good-bye to Miss Porter I walked home with them as far as Linden Gardens. Got in at 11.30 very tired indeed and glad of my supper. Mother was waiting up.

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – e.crawford@sphere20.freeserve.co.uk (£14.99 +UK postage £3. Please ask for international postage cost), or from all good bookshops. In stock at London Review of Books Bookshop, Foyles, National Archives Bookshop.