Archive for category The Garretts and their Circle

The Garretts And Their Circle: UPDATED: Even More Annie Swynnerton Revelations

Posted by womanandhersphere in Art and Suffrage, The Garretts and their Circle on March 30, 2023

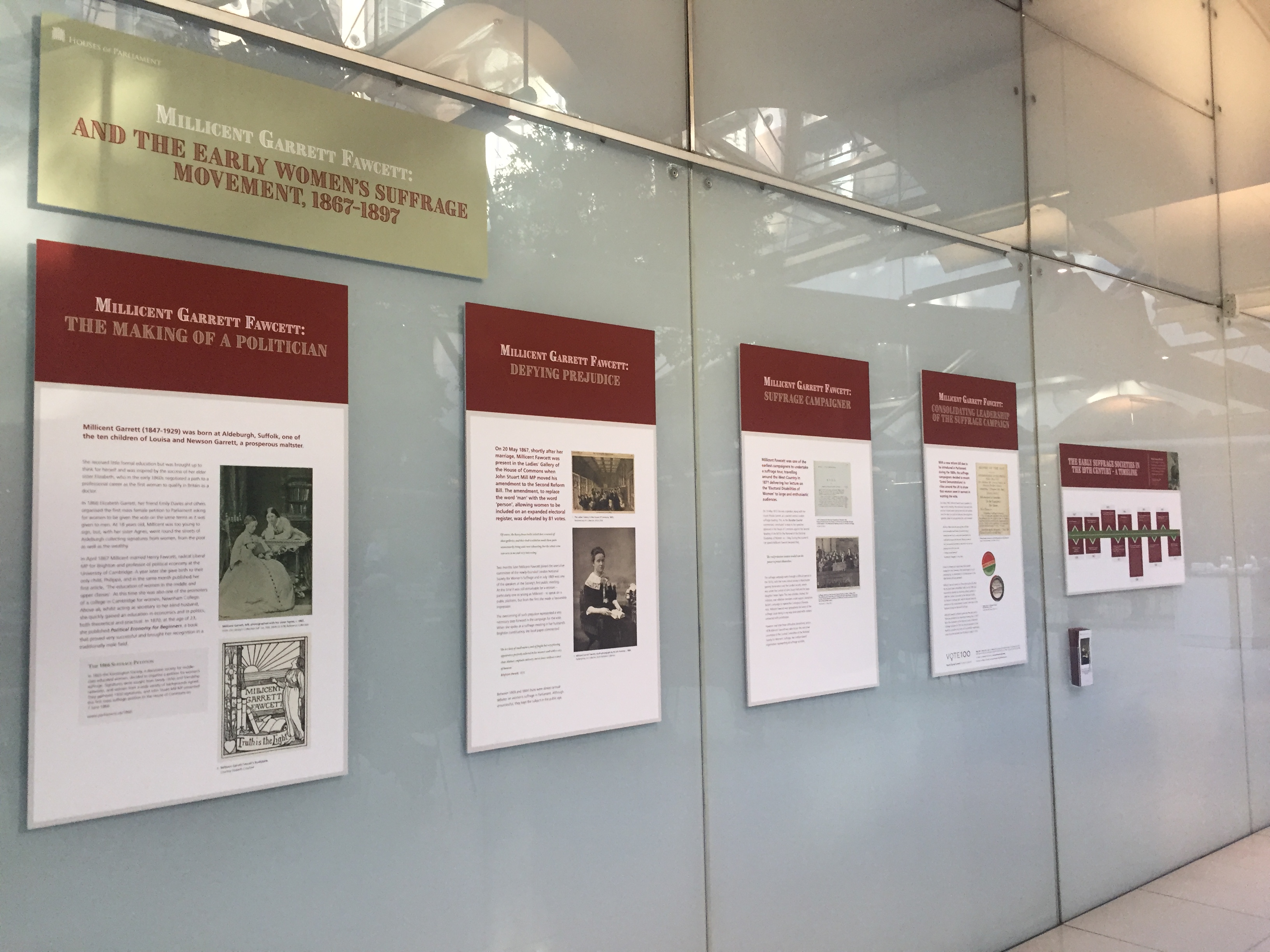

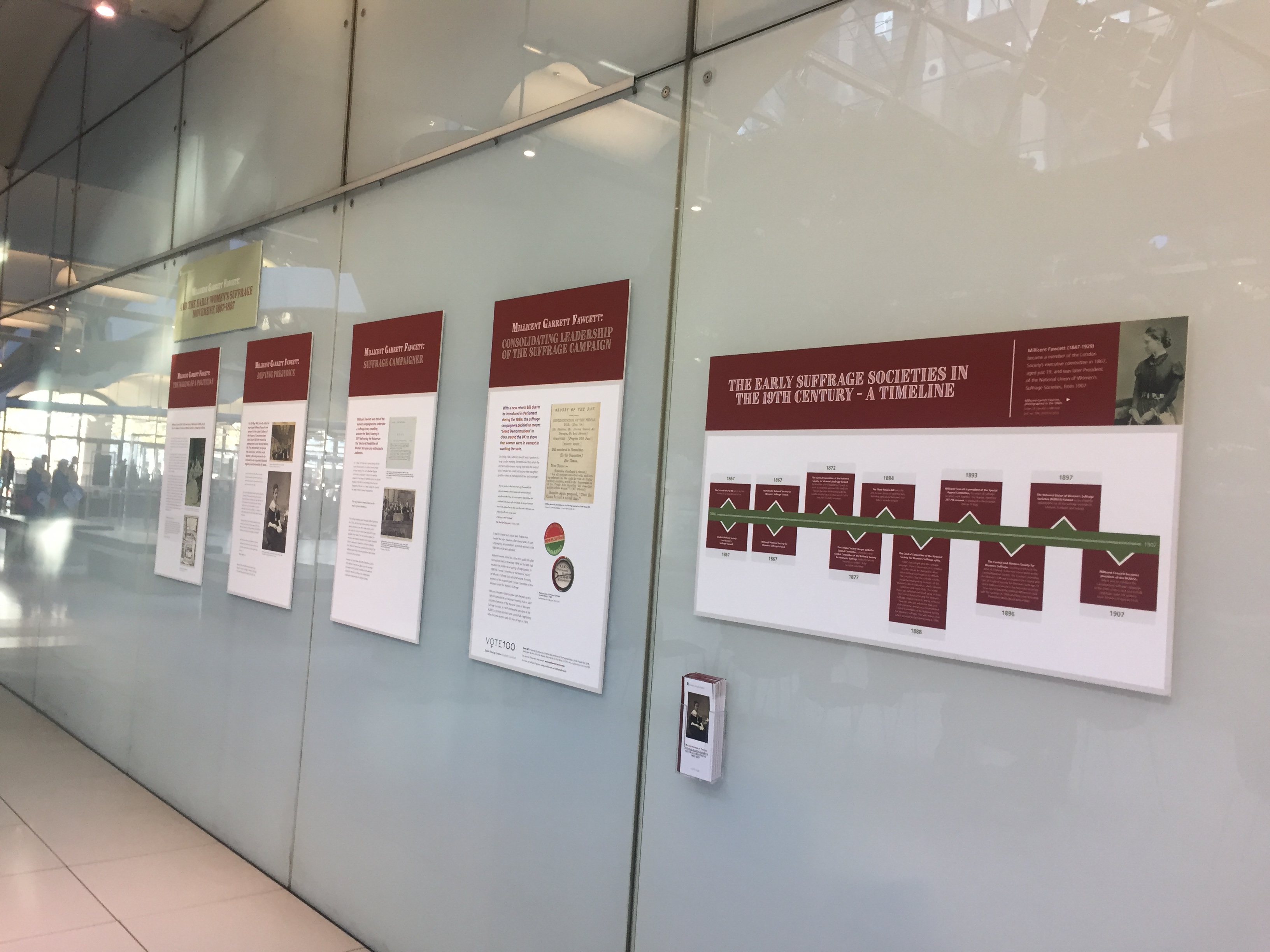

Excellent News: Millicent Garrett Fawcett has now entered Parliament. A portrait of Millicent Garrett Fawcett by Annie Swynnerton, acquired by The Speaker’s Advisory Committee on Works of Art, was ‘unveiled’ on 27 March 2023. The event, chaired (vivaciously) by Jess Phillips MP, was notable for talks on the sitter and the artist by Prof. Melissa Terras and Dr Emma Merkling.

UPDATE

I wrote a long post earlier this month – revealing the existence of previously unknown collection of Swynnerton portraits, the existence of which enhances our knowledge of the artist. Since then I have tracked down one further associated portrait. Rather than merely issuing a short post with the new information, I thought it best, for completeness, to update the existing post. The ‘new’ portrait is discussed towards the end of this article, the main body of which has been amended where necessary.

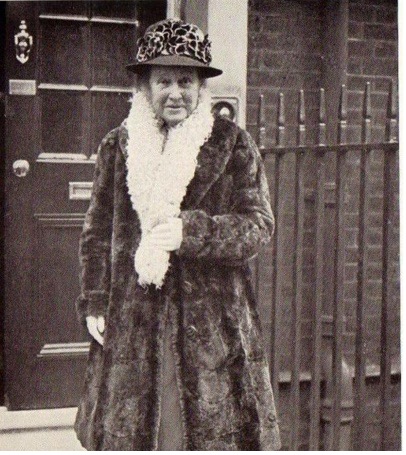

Millicent Garrett Fawcett by Annie Swynnerton (Courtesy of The Speaker’s Advisory Committee on Works of Art)

It was in July 2022 that I noticed the portrait had appeared in an art dealer’s listing and immediately alerted Melanie Unwin, who until recently was Deputy Collector of the Palace of Westminster Collection – exclaiming, ‘Now, wouldn’t this be an excellent addition to the Parliamentary Collection?’ And – it has come to pass. Public recognition of Millicent Fawcett is something in which I have taken a personal interest – for ten years ago I posted on this website a plea – ‘Make Millicent Fawcett Visible’. And now, lo – the veil has been lifted – she now has a statue in Westminster Square, her portrait, by Annie Swynnerton, is on show in the Tate,[i] and this other version will now hang in Parliament.

This version, which presumably was painted around the same time (1910) as that bought for the Tate by the Chantrey Bequest in 1930 (the year after Fawcett’s death), remained, for whatever reason, in Annie Swynnerton’s studio and was sold in the February 1934 posthumous sale of her ‘Artistic Effects’. After that it passed through the auction rooms on several occasions but since the early 1970s has remained out of sight. However, thanks to the fact that the National Portrait Gallery archive holds a black-and-white photograph, Melissa Terras and I were able to include this image in Millicent Fawcett: selected writings.[ii]

In Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle I hazarded a guess that the Tate’s portrait might have been painted in a first-floor back room at Fawcett’s home, 2 Gower Street, Bloomsbury. However, I’ve now discovered, in a recently-digitised newspaper (the wonder of our age), that ‘Mrs Swynnerton told a Daily Herald representative that half of the portrait was painted in the garden of Dame Millicent’s house in Gower Street and the other half at her own home’.[iii]

Which leads me neatly to the bland, but intriguing, observation that a narrative is shaped by the available information. Thus, in biography, an author takes ‘facts’ about a subject and turns them into a ‘life’. If the ‘facts’ comprise primary sources, such as letters, diaries, newspaper articles, society minutes, oral interviews etc, so much the better – or, at least, easier. But if the subject has left no written trace, information must be wrung from whatever material comes to hand.

And, thus, I leap to the particular. For, in the case of the artist Annie Swynnerton (née Robinson), although there is very little documented information about her early life, serendipity – in the shape of a previously unrecorded collection of family portraits – has recently allowed me to focus the biographical lens on one connection made at the start of her career, that ran as a thread through its entirety, ensured her a place in the canon, and effected the link between the artist and the sitter of Parliament’s latest acquisition.

We know Annie Louisa Robinson was born in Manchester in 1844, the eldest of seven daughters. Her father, Francis Robinson (1814-89), the son of a Yorkshire carpenter,[iv] had risen from what one assumes were relatively humble beginnings, to become a solicitor, with a practice in central Manchester. By the mid-1850s he was sufficiently successful to be able to move his growing family from inner Manchester to a newly-built, detached house in leafy Prestwich Park, 5 km north of the city.[v] In fact Robinson was one of the first house-owners in this development which, guarded by two entrance lodges and with fine views, was intended to appeal to the burgeoning Manchester middle-class.[vi] For some years Robinson involved himself in Manchester affairs; in 1863 he was vice-president of the Manchester Law Association and from at least 1861 was a councillor for St Ann’s Ward and by 1868 its chairman. However, in 1869 disaster struck; he was declared bankrupt. The effect on the family was momentous. In March the entire contents of the home – from a ‘Splendid Walnutwood Drawing-Room Suite, ‘’a sweet-toned cottage pianoforte’, ‘stuffed Australian birds under glass shade’ to a ‘patent coffee percolator’, ‘large brass preserving pans’, and ‘300 choice greenhouse and other plants’ – were all sold at auction.[vii] Stripped from the walls were oil paintings by, among others, Sam Bough, John Brandon Smith, and David Cox, and, from the bookshelves, about 500 volumes, among which were Bryan’s Dictionary of Painters and Engravers.

In June the house itself, with its drawing-room, two dining rooms, breakfast room, library, nine bedrooms, bathrooms, pantries, sculleries, and about half an acre of land, was sold.[viii] The family was then split up. The 1871 census shows Annie (27, Artist), living with her sisters Emily (26, Artist), Julia (24, Artist), Mary (Scholar 16) and Frances (Scholar, 14) in lodgings at 28 Upper Brook Street, back in central Manchester, while Sarah (22) and Adela (19) were visiting with Mrs Sarah Robinson, an elderly widowed relation, and their aunt Mary on the other side of the same street, at number 13.[ix] There is no trace of the Robinson parents in the census but, wherever they were, on census night at least, they were not living with any of their daughters. We must assume that the older sisters now had responsibility for the younger two, who were still at school.

We have no information as to where or how Annie and her sisters were educated. The 1861 Robinson household census does not include a governess, so we can probably conclude that the girls attended a school.[x] Published 30 years later, a brief biographical article in The Queen gives us a rare insight into the Robinson sisters’ early life.[xi]

‘Curiously enough, whilst neither parent had any taste in that direction, Mrs Swynnerton’s two sisters Emily and Julia, were, like herself, born artists, and are both practising their profession in Manchester. When of the tender age of from eleven to thirteen years, Miss Annie used to delight her playfellows, visitors to the house, and the servants with exhibitions of specimens of her very juvenile skill in the shape of water-colour drawings. These primitive works were produced without the advantage of any instruction, and were simply the spontaneous efforts of an inborn, absorbing love of art.’

The Queen commends Francis Robinson for recognising his eldest daughter’s talent and states that ‘she was early placed in the art school at her native city, Manchester’, making no mention of the family’s financial disaster that probably necessitated, or, at least, precipitated, this development. Bankruptcy was unlikely to have struck suddenly and Annie and her sisters may well have been aware of impending disaster. That may be why, from sometime from 1868, Emily, Annie and Julia enrolled as students at the Manchester School of Art. Sensible young women knew a training was necessary if a living was to be earned. Certainly by 1870/1871, with the security they had once enjoyed swept away, the three oldest Robinson sisters were all attending classes at Manchester School of Art.[xii] Here Annie excelled and in 1873 was awarded one of the 10 national gold medals and a Princess of Wales scholarship worth £11 for ‘Group in oils’.[xiii] Julia was presented with a bronze medal and Emily a book prize.[xiv]

In tracing Annie’s developing career I will continue with the known facts and return later to suppositions. Thus, the narrative runs that in 1874 Annie Robinson travelled to Rome with her friend Isabel Dacre to study and paint, returning to Manchester in 1876. We do not know exactly when in 1874 they left Manchester, nor exactly when in 1876 they returned. But we do know that Annie exhibited a painting at the Manchester exhibition in March 1877.[xv]

Mrs Louisa Wilkinson by Annie Swynnerton (credit Kenneth Northover)

Annie was again successful the following March (1878) in having another painting selected to hang in the Manchester exhibition. Most importantly, this was the first of her works to which the name of the subject was attached, a name that was then included in the press reports. [xvi] The painting was a full-length portrait of Mrs Louisa Wilkinson and is the first, dated, evidence of Annie’s lifelong friendship with the Wilkinson family, about which I write in Enterprising Women. When researching and writing that book, I guessed that the Wilkinsons, a leading Manchester family, were likely to have been the conduit through whom Annie entered the Garrett Circle, but until recently I had no material proof of when the connection might first have been made.

Revelation struck in June 2022 on a particularly serendipitous occasion, held to mark the installation, on her one-time Bloomsbury apartment, of an English Heritage Blue Plaque to Fanny Wilkinson (1855-1951), Britain’s first professional woman landscape gardener. It was my research on Fanny, published in Enterprising Women, that directed attention to her work, and I was delighted to listen as a descendant of her youngest sister gave a talk about the Wilkinson family – and was astounded when a portrait of Fanny, by none other than Annie Swynnerton, appeared on the accompanying Powerpoint. During the reception that followed I was thrilled to discover that a South African branch of the family held other portraits of family members painted by Annie, both before and after her marriage. This cache of paintings, previously unknown to the art world, presents us with a key to unlock more information about Annie’s career.

For among these family portraits is the painting of Mrs Louisa Wilkinson (1823-89) that was exhibited in Manchester in 1878. Here she is, fashionably attired in satin, lace, and jewels, her dress, with its swagging, rosettes, ruches, and train, affording Annie every opportunity of displaying a bravura technique. The Wilkinsons were wealthy and philanthropic; there is no doubt that Annie would have been well paid for the portrait. In addition, by permitting her portrait to be exhibited and allowing herself to be named, Mrs Wilkinson was furthering Annie’s cause by advertising her skill. To attract clients from Manchester’s prosperous middle-class an artist had to be able to display their work. Were the Wilkinsons Annie Robinson’s first significant clients?

It may be that Annie received similar portrait commissions at this time but because they were not exhibited by name (or, indeed, have subsequently passed through the auction rooms with no name attached) they are now unknown. The one portrait by Annie that did receive attention in the late 1870s was that of the Rev. W. Gaskell, widower of the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, which was commissioned by the Portico Library. It was the Rev. Gaskell himself who in 1879 chose to be painted by Annie, remarking ‘My daughters tell me that she has painted a portrait which they like very much.’[xvii] Could it have been the portrait of Mrs Louisa Wilkinson to which they were referring?[xviii]

For the Gaskells and Wilkinsons must surely have known each other. Dr Matthew Eason Wilkinson (1813-78) was Manchester’s leading doctor and his wife, although born in the US, was descended from a radical Manchester family. The Wilkinsons took an interest in art; Fanny, the eldest, put an artistic ‘eye’ and practical ability to good use in forging a novel career, while both Louisa (1859-1936) and Gladys (1864-1957) studied art in London and had works exhibited.

But, to return to the portrait of Mrs Louisa Wilkinson. To have been exhibited in March 1878, this portrait must have been painted sometime earlier, which places Annie firmly in Manchester for at least some of 1877 and, probably, part of 1876. It so happens that the ‘manly, intellectual head’ of Mrs Wilkinson’s husband, Dr Matthew Eason Wilkinson, was, in the autumn of 1877, on display in the studio exhibition of a sculptor, Joseph Swynnerton.[xix] I think, therefore, we can be certain that, whether or not they had known each other previously (and surely they had), the artist and the sculptor must have encountered each other at this time, as they each immortalised Wilkinson père and mère, a pattern repeated the following year when they both produced portraits of the Rev. Gaskell, one in oils and one in marble.

Louisa Wilkinson – second daughter of the Wilkinson family (credit Kenneth Northover)

It was another eleven years before another Annie Swynnerton portrait of a fully-named member of the Wilkinson family was exhibited – and that is this full-length portrait of Louisa Mary Wilkinson, shown at the New Gallery in April/May 1889 . The change of style is remarkable. Louisa was described in the Pall Mall Gazette as ‘a slim figure with an old-fashioned face out of a Dutch picture standing among bluebells and clasping an illuminated missal,[xx] while the Birmingham Daily Post considered it a ‘very original and unconventional portrait, which we found a great deal more human and interesting than the silk and satin gowns with long trains, the feather-fans ad bric-a-brac, with figure-heads attached’.[xxi]

It is now possible to insert a biographical ‘fact’ that may give a slight narrative depth to this picture. For when it was painted, 1888/9, although renting a studio at 6 The Avenue (76 Fulham Road), Annie and Joseph were actually living in Bedford Park, the ‘Queen Anne’, ‘Sweetness and Light’, suburb so popular with artists, their house, 18 St Anne’s Grove, having a purpose-built studio on the top floor.[xxii] At the same time, Mrs Louisa Wilkinson was also a resident of Bedford Park. Although Fanny was living in Bloomsbury, it’s likely that Louisa and her younger sisters lived, at least some of the time, with their mother.[xxiii] I don’t think it too fanciful to suggest that the younger Louisa Wilkinson may have been painted in Bedford Park – standing amongst bluebells (the image I reproduce is, perforce, cropped) either in the garden of Annie’s house or that of her mother.

A few years earlier Louisa had been recorded in the 1881 census as an art student, exhibited that year in the Dudley Gallery and in 1882 at the Walker Gallery, and later turned her hand to book binding. Thus, it’s fitting she’s depicted wearing Artistic Dress, her loose linen garment, with tucks, shoulder embroidery and bodice smocking, cinched by an embroidered belt, hinting at an artist’s smock. She wears no necklace or earrings, the illuminated missal offering sufficient jewelled colours. Perhaps she had bound the missal herself.

In 1894 Annie exhibited the portrait again, including it in a Society of Lady Artists exhibition. Fortunately, the review in The Queen allows us to identify this as the same portrait, by including a description of ‘Portrait of Miss Louisa Wilkinson’: ‘a finely executed picture of a lady facing the spectator, holding, apparently, an illuminated missal in her hands. There is a strong sense of harmony in the scheme of colour, in which a reddish-brown costume plays a not inconspicuous part’. [xxiv] The Manchester Evening News described the portrait as a ‘very “new English” full-length study’.[xxv] Although Annie was not elected a member of the New English Art Club until 1909, she had long been responsive to works by such earlier members as George Clausen.

The two paintings, so different in style – that of Mrs Louisa Wilkinson exhibited in 1878 and her daughter, Louisa, in 1889 – are the only two of Annie’s Wilkinson portraits that were exhibited by name. But they are not the only family portraits by her still held by Wilkinson descendants. As I’m keen to keep supposition separate from known facts, I’m now discussing these separately, rather than inserting them into the known Annie Robinson/Swynnerton chronology.

Jean (on the left) and Gladys Wilkinson (credit Kenneth Northover)

It is possible that the above portrait could have been the first that the Wilkinson family commissioned from Annie. The biographical article published in The Queen mentions that Annie’s ‘.. first picture was a profile picture of a girl’s head, and this she followed with a group, two half-length portraits, called “Gladys and Jean”, which was in the Manchester exhibition.’

Gladys and Jean were the youngest members of the Wilkinson family, born in 1863 and 1876. How old do you think they look in this painting? To me it doesn’t seem possible they could be older than 11 and 7 respectively and that, if so, the double portrait must have been painted no later than 1873/1874, before Annie’s departure abroad.[xxvi] Even in this imperfect photo, we can see that the girls’ satin and lace dresses – and the fashionable Japanese fan held by Gladys – have been lovingly detailed by Annie. It seems plausible that the Wilkinson parents would have commissioned a smaller portrait of their youngest daughters, as a test run, before incurring the expense of a full-length painting of their mother. If The Queen journalist was correctly informed and the painting was indeed exhibited in Manchester, it could have been included in the 1875 Royal Manchester exhibition, the first for which ‘lady exhibitors’, of whom Annie was one, were eligible.[xxvii] Or could it even have been the ‘group in oils’ (which is an echo of the term used of ‘Gladys and Jean’ in The Queen)for which Annie won her Princess of Wales scholarship in 1873? But that is probably too fanciful – and an illustration of how dangerous it is to view a ‘biography’ through a single lens.

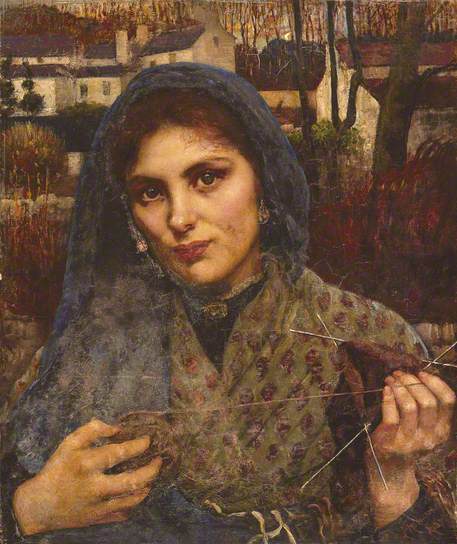

Fanny Wilkinson by Annie Swynnerton (credit Kenneth Northover)

Here, now, is the portrait of a demure Fanny Wilkinson that put me on the trail of the cache of ‘Wilkinson’ paintings. Although it probably does carry a date, that cannot be seen at the moment, and, although it’s possible to gauge the age of young children such as Gladys and Jean, it’s more difficult to do so for a young woman. Although I cannot decide whether it was painted before or after Annie’s stay in Rome (1874-6), I think we can be certain that the portrait was painted before the death of Dr Wilkinson in Autumn 1878 and the family’s consequent move from Manchester to Middlethorpe Hall in Yorkshire.

Fanny is depicted as decidedly ‘Artistic’, the sleeves of her dress bound in a quasi-medieval style, a lace fichu flowing over the bodice, complementing the frothing cuffs. Although we cannot see the whole shape of her dress, it certainly appears more relaxed than her mother’s ruched and flounced costume. The peacock feathers were, of course, the height of Aesthetic accessorizing. The accomplished painting of the yellow satin and the lace once again advertised the artist’s skill. I wonder if the portrait was ever exhibited? I don’t think it can be the ‘profile picture of a girl’s head’ mentioned in the 1890 Queen article – as it’s so much more than ‘a head’.

Louisa Wilkinson by Annie Swynnerton (credit Kenneth Northover)

This is the last of this particular collection of Wilkinson portraits – a sketch of Louisa in a sun bonnet. It is signed ‘A.L. Swynnerton’ and so can be dated to no earlier than 1883 – and her marriage to Joseph – but could perhaps be any time after 1887 (for in that year she was still signing paintings as ‘Robinson’) but before Louisa’s marriage to George Garrett in 1900 (because the title on the frame refers to her as ‘Wilkinson’).[xxviii]

This marriage merely formalised the link between the Garrett and Wilkinson families, the women having already been bound for over two decades in friendship and shared enterprises, with Annie as their preferred portraitist. However, besides the portraits noted above, I knew that Annie Swynnerton had painted another portrait of Louisa Garrett/Wilkinson because I had, very much in passing, seen it when researching Enterprising Women, well over 20 years ago. It was then hanging in a house in Aldeburgh, the home of the widow of a descendant of the wider Garrett family who had inherited ‘Greenheys’ (the Snape home of George and Louisa Garrett). I was there attempting to track down information on the work of Rhoda and Agnes Garret and, although noting the portrait with interest, did not, at the time, record it in any way. But, its existence, if not its form, remained in my memory and in very early 2020, shortly before Covid descended, I set out to try and track it down – and yesterday succeeded.

Louisa Wilkinson (later Mrs George Garrett) by Annie Swynnerton (credit Peter Wood)

The portrait of Louisa Wilkinson is particularly interesting for having Annie Robinson’s monogram prominently displayed in the top left corner. Moreover, I believe it is the painting, catalogued as ‘Louise’, that Swynnerton exhibited at the Walker Gallery, Liverpool, in September 1878. The critic in the Liverpool Mercury (23 September 1878) praised it as ‘A very pleasing and clever picture, unassuming in character of both work and individual; no ostentation, no gilding of nothingness, but a really fine painting. A young and thoughtful face, neat costume, chaste subdued colouring, and good workmanship, make it a work of beauty and promise much to be admired.’

I think, too, that this is ‘Portrait of a Lady’ that Swynnerton exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1879. I make this deduction from an intriguing comment made in the course of an article about Swynnerton that appeared in the 1890 Queen article. In it the writer remarks of her work that ‘An excellent picture, “Louise”, was placed on the line at the RA, this being succeeded by “The Tryst”.’

It is difficult to interpret this remark. Although ‘The Factory Girl’s Tryst’ was shown at the RA in 1881, preceded in 1879 by ‘Portrait of a Lady’ and in 1880 by ‘Portrait of Miss S. Isabel Dacre’, Annie doesn’t appear ever to have exhibited any ‘Louise’ (or ‘Louisa’) at the RA. Unless, of course, the Queen journalist was told that the 1879 ‘Portrait of a Lady’ was that of a particular ‘Louise’ (or ‘Louisa’), in which case it must surely be the portrait exhibited in Liverpool the previous year.

In 1879 The Athenaeum’s reviewer described the RA portrait as of a ‘lady in a grey citron dress, standing against a grey background [which] shows profitable studies of old Italian portraiture with Dutch vraisemblance, and is the first-rate example of the harmonious treatment of low tints and tones in a manner that is not decorative ‘[xxix] What do you think? Could this accord with what you see in the portrait of Louisa Wilkinson? After Liverpool in 1878, was she re-shown at the RA in 1879? As we can see, from the three known portraits, Louisa Wilkinson/Garrett was one of Swynnerton’s favourite subjects. If this was the first, Louisa would have been c 19 in 1878, an age consonant with the sitter of ‘Louise’, Knowing that Swynnerton had also recently painted her mother and three of her sisters, it seems entirely credible that this portrait of Louisa would have been painted in 1878 and, hence, that it is the portrait exhibited at the Walker Gallery and the Royal Academy.

I also know that, over the years, Swynnerton painted Louisa Garrett Anderson (daughter of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and niece of Millicent Fawcett) and Rhoda Garrett (cousin and partner of Agnes Garrett), although their whereabouts is not now known. However, in the course of researching this article I think I have made one discovery.

Agnes Garrett by Annie Swynnerton (courtesy of Lacy Scott and Knight)

For, on Jonathan Russell’s excellent website, under details of the paintings shown at the 1923 exhibition of Annie’s works, I came across this – described as ‘Portrait of a lady standing by flowering ivy’. It was sold, unframed, at auction twice, in quick succession, in 2014.[xxx] I am certain that this is the portrait that Annie painted of Agnes Garrett – at Agnes’ holiday home in Rustington, in the summer of 1885. The subject not only looks like Agnes, but I can see Sussex knapped flints in the wall behind her. This painting was included in the 1923 Manchester exhibition of Annie’s works – and I know that Agnes’ portrait was also there, in Room 7, lent by her sister-in-law, Louisa Garrett. This must surely be it.

In Enterprising Women I describe in detail how the Wilkinsons, the Garretts, and other members of their circle did so much – through their ‘matronage’ – to ensure Annie Swynnerton’s presence on art gallery walls. And she, in turn, has ensured that her friends and associates, as they hang on the walls of family homes, are still known to their descendants.

You can find other posts about Annie Swynnerton on this website by putting ‘The Garretts and their Circle’ into the Searchbox.

For International Women’s Day 2023 the Pre-Raphaelite Society invited me to talk about Annie Swynnerton. You can find the resulting 2 podcasts here.

[i] When, c. 2000, I was researching Enterprising Women:the Garretts and their circle (Francis Boutle, 2002) the I had to visit the Tate storage facility in order to view the Swynnerton portrait of Millicent Fawcett. It was subsequently shown in Wales, at Bodelwydden Castle, but returned to London for the suffrage centenary in 2018.

[ii] M. Terras and E. Crawford (eds), Millicent Garrett Fawcett: selected writings, UCL Press. Free to download https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10149793/1/Millicent-Garret-Fawcett.pdf p 315.

[iii] Daily Herald, 7 May 1930, 1. Swynnerton’s home and studio in 1910 was 1a The Avenue, 76 Fulham Road, London W.

[iv] Information from Francis Robinson’s Articles of Clerkship, 1836 via Ancestry.

[v] I note that the two youngest Robinson daughters were both born in Prestwich. The elder, Mary, was baptised at St Mary’s, Prestwich, on 3 March 1856.

[vi] For something on the history of Prestwich Park see https://www.bury.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5382&p=0. In the advertisement for the sale of the Robinsons’ household goods in the Manchester Courier, 6 March 1869, the house was described as ‘the second house from the Bottom Lodge, Prestwich Park.

[vii] Manchester Courier,6 March 1869.

[viii] Manchester Courier, 5 June 1869.

[ix] C. Allen and P. Morris, Annie Swynnerton: painter and pioneer, Sarsen Press, 2018, identifies the widowed relation as Francis Robinson’s stepmother

[x] In 1861 Miss Hannah Dickinson’s Ladies’ College opened at Hill-side House, in Prestwich Park, close to the Robinsons’ home. Although Annie would have been then too old, it’s unlikely that even her younger sisters were pupils, as Its fees, even for day girls, were high, 16-20 guineas per annum. Miss Dickinson stressed that she had chosen Prestwich Park for its ‘beautiful scenery, its rural glens, its retired walks, and salubrious breezes – as well as ‘its kind-hearted inhabitants’. Miss Dickinson, Thoughts on Woman and Her Education, Longman Green, 1861, p2

[xi] The Queen, 15 March 1890.

[xii] No firm, primary, evidence has come to light as to when exactly the sisters – either individually or together – enrolled at the School of Art. However, Allen and Morris (p. 19) have established very persuasively that Emily ‘was certainly there from at least autumn 1868’ and that Annie, too, had probably been enrolled in 1868, and Julia certainly by 1869-70.

[xiii] Manchester Evening News, 20 August 1873.

[xiv] Manchester Courier, 13 July 1874.

[xv] It was only in 1875 that 9 ‘Lady exhibitors’ were elected for the first time – among whom were Annie Robinson and Isabel Dacre.

[xvi] ‘Miss Annie L. Robinson has a large full-length portrait of Mrs. Eason Wilkinson … and although defective in some respects, gives promise of better work in the future.’ (The Manchester Courier, and Lancashire General Advertiser, 8 March 1878.)

[xvii] Rev. Gaskell quoted in B. Brill, William Gaskell, 1805-84: a portrait, Manchester Literary and Philosophical Publications, 110-11.

[xviii] The portrait of the Rev. Gaskell now hangs in the Gaskells’ former home – see https://elizabethgaskellhouse.co.uk/

[xix] Manchester Times, 6 October 1877. Dr Wilkinson was that year president of the British Medical Association, whose meeting had been held that summer in Manchester. The portrait bust may have been intended to mark this achievement. I have no knowledge of what has become of it. Swynnerton’s studio was at 35 Barton Arcade. In 1880 the address of the Manchester Society for Women Painters was 10 Barton House, Deansgate, which must have been close to the Arcade.

[xx] Pall Mall Gazette, 1 May 1889. At this time both artist and sitter had moved from Manchester; Annie had a London base at the Avenue Studios, 76 Fulham Road, W. and Louisa Wilkinson was living, with her sister Fanny, at 15 Bloomsbury St, WC.

[xxi] Birmingham Daily Post, 18 May 1889.

[xxii] Annie gave th e St Anne’s Grove address when she submitted work in 1888 to the Society of Women Artists and the Swynnertons were still living there in 1891. However, it is only Annie’s name – and that of her Aunt Mary and their one servant – that appears on the census because the previous page, which must include Joseph as the last entry, is missing – or has been missed when scanning. The page reference that shows Annie’s presence at 18 Queen Anne’s Grove is RG12/1038 folio 8 page 33 schedule 193. Information on the Swynnertons’ occupation of these addresses can be found in the London Electoral Register via Ancestry.

[xxiii] Mrs Wilkinson was living in Bedford Park from at least 1886 and died there in 1889. Her house is only referred to as ‘The Chestnuts’ and I have been unable to discover the exact address.

[xxiv] The Queen, 28 April 1894.

[xxv] Manchester Evening News, 21 April 1894.

[xxvi] The double portrait of ‘Gladys and Jean’ may be dated, but at the moment that information is not accessible.

[xxvii] Alas, I have not yet been able to consult the catalogue for this exhibition. If anyone does know if a portrait by Miss Robinson of two young girls was included do, please, let me know.

[xxviii] For information about the change of signature see https://annielouisaswynnerton.com/ordered-by-date/ .

[xxix] Thanks to Julie Foster for pinpointing the Liverpool Mercury reference. The Atheneum, 5th and concluding notice of RA Summer Exhibition, 7 June 1879,734.

[xxx] . Unfortunately, neither of the East Anglian auction houses who sold the painting holds records as far back as 2014 and I’ve been unable to discover any more information about the painting, or its current whereabouts.

ANNIE SWYNNERTON: My Podcast for the Pre-Raphaelite Society

Posted by womanandhersphere in Art and Suffrage, The Garretts and their Circle on March 8, 2023

The Garretts And Their Circle: Millicent’s Writings (soon to be published) And Agnes’ Furnishings (work in progress)

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on March 8, 2022

This International Women’s Day I would like to celebrate, once again, the work of the women of the Garrett family.

In a couple of months’ time UCL Press will be publishing Millicent Garrett Fawcett: Selected Writings on which I have had the pleasure of working, alongside the lead editor, Prof Melissa Terras. In the volume, which will be open access as one of the publishing options, 35 texts and 22 images are contextualised and linked to contemporary news coverage, as well as to historical and literary references. This is the first opportunity to study in one volume Millicent Fawcett’s thinking on a range of topics concerning the advancement of women, of which the women’s suffrage campaign is only one.

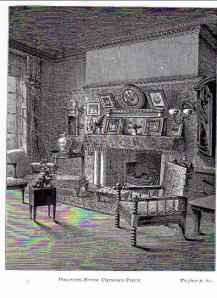

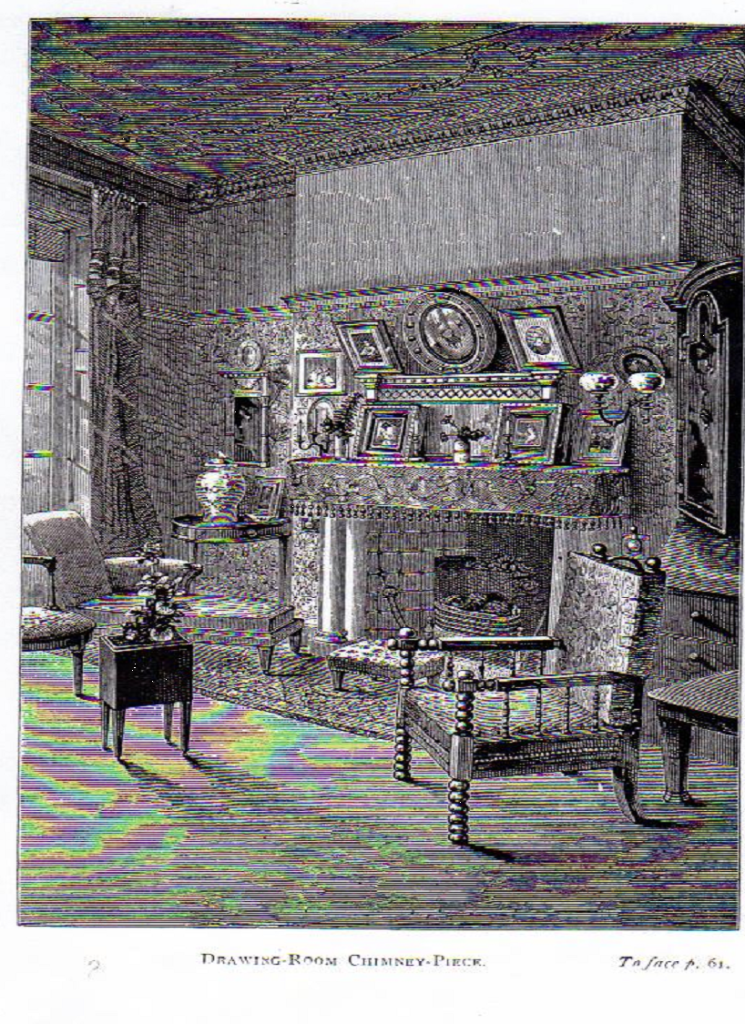

In the photograph we chose as the cover for the book you see Millicent Fawcett seated at her desk in a corner of the first-floor front drawing-room of her home at 2 Gower Street, Bloomsbury. It may be the very same desk as that of which we catch a glimpse, to the right of the fireplace in the illustration below, taken from Suggestions for House Decoration (1876) by Rhoda and Agnes Garrett. Many years ago, after visiting 2 Gower Street when researching Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle, I came to the conclusion that the illustrations in House Decoration were taken directly from real life, that is they were pictures of the rooms in 2 Gower Street, as arranged by Rhoda and Agnes. Recently I have been delighted to have my educated guess vindicated by discovering that Lady Maude Parry, a friend of the Garretts, stated in an obituary article on Rhoda, published in Every Girls’ Annual 1884, that in Suggestions for House Decoration ‘are illustrations of their house in Gower Street’.

Rhoda died in 1882, but Agnes carried on the business of ‘R & A Garrett’, house decorators, until 1905, although in 1899 the lease on the firm’s warehouse in Morwell Street came to an end, necessitating the sale of its contents and, presumably, a reduction in the work undertaken. Incidentally the Morwell Street building and its neighbours has recently, 2022, been approved for demolition, to be replaced by a 6-storey building. When I first noted it c 2000, the Garrett’s ‘warehouse’ retained its original façade (illustrated in Enterprising Women), which has subsequently been altered – now another Garrett link will be utterly obliterated. However, that furniture sale, held at Phillips, Son and Neale on 27 July 1899, has provided me with considerable scope for research – allowing me to identify a number of individuals keen to buy furniture and house accoutrements that had the Garrett seal of approval – in that they had passed through Agnes’ hands – and to muse a little on the state of the ‘house furnishing’ market at the end of the 19th century. That research will appear in a subsequent post on this website.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement

The Garretts And Their Circle: A Talk on Fanny Wilkinson

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on May 12, 2020

Lock-Down Reviews: The Lives And Work Of Two Garrett Cousins: ‘Endell Street’ and ‘Margery Spring Rice’

Posted by womanandhersphere in Lock-Down Research, The Garretts and their Circle on May 6, 2020

Serendipitously, lock-down has given me the opportunity of making closer acquaintance with two cousins, products of that ever-interesting family – the Garretts.

Louisa Garrett Anderson and Margery Spring Rice, members of the generation that came after the pioneering Garrett sisters Elizabeth, Millicent and Agnes, are each the central figure in new books spotlighting aspects of ‘women’s work’ that, although not forgotten, have hitherto not received detailed attention. The books differ in concept in that one is a study of an enterprise and the other is a straight biography, but central to both is evidence of a steely Garrett determination.

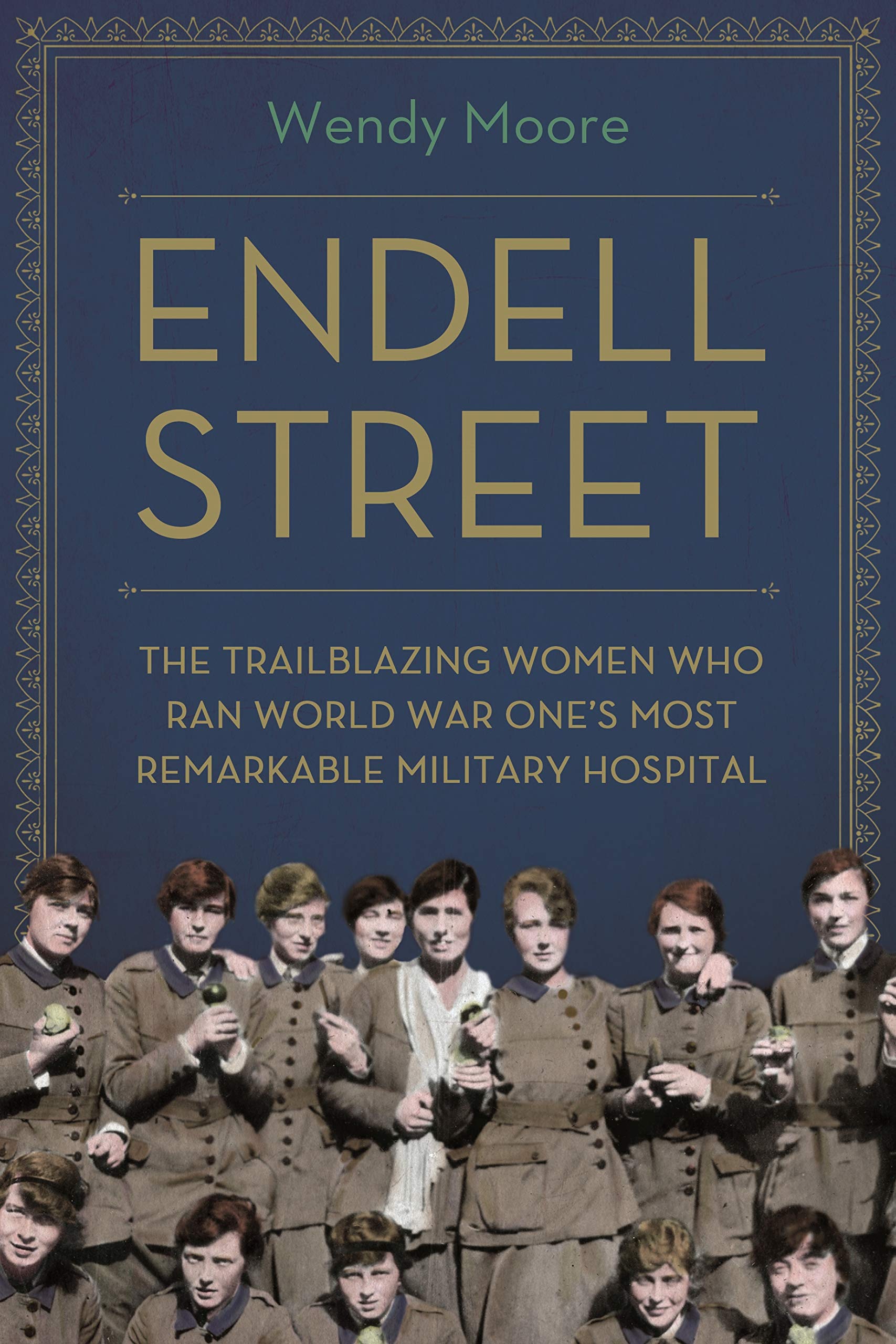

Endell Street by Wendy Moore is a study of the military hospital opened in London during the First World War by Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson and her companion, Dr Flora Murray. The hospital was exceptional in that it was the first in which women doctors were able to treat male patients. In fact, the entire staff (with the exception of a few orderlies) consisted entirely of women. Although Dr Murray recounted the work of the hospital in Women as Army Surgeons, published in the immediate aftermath of the war, it is certainly time, a hundred years later, to look at it with fresh eyes.

Louisa Garrett Anderson (1873-1943), daughter of Britain’s pioneer doctor, Elizabeth Garrett, and Flora Murray (1869-1923), daughter of a retired Scottish naval commander, had both studied at the London School of Medicine for Women, with Murray finalising her degree at Durham University. At the turn of the 20th century women doctors still faced considerable difficulty in advancing their careers and Garrett Anderson and Murray, denied positions in general hospitals, were restricted to treating women and children. The professional difficulties with which they had to contend forced them away from the constitutional suffrage movement, led by Louisa’s aunt Millicent, and into Mrs Pankhurst’s militant WSPU. Garrett Anderson even spent time in prison after taking part in a 1912 protest.

Medal issued by the Women’s Hospital Corps. For sale 0 see item 512 in my Catalogue 202 Part 2

The outbreak of war in August 1914 offered an opportunity to escape the medical cage, an opportunity seized by Garrett Anderson and Murray with both hands. Their offer to help in the war effort having been repudiated by the authorities, they struck out on their own. travelling to France in September 1914 to tend wounded soldiers in hospitals they set up themselves, first in Paris and then in Wimereux. They named their outfit the Women’s Hospital Corps and It was the success of these first, small, French-based operations that led them in 1915 to be invited by the War Office to run a military hospital in London. They opened it in an old workhouse in Endell Street, Covent Garden, convenient for the trains bringing the wounded back from France. All involved with the Endell Street hospital were aware that they were operating on sufferance and that any lapse of standards would damage the professional chances of future women doctors

The author has researched diligently, enlisting the aid of diaries, letters and family memories of both staff and patients to paint a more inclusive picture of the hospital and its occupants than that depicted by Dr Murray. These reveal how demanding the work was of all the women. Stretcher bearers and surgeons alike tackled situations they had never previously encountered. Louisa Garrett Anderson was the hospital’s main surgeon and Flora Murray its anaesthetist. Obviously neither they, nor the other women doctors on the staff, had any previous experience of the types of wounds – and patients – they were now treating, but proved very competent in developing the necessary skills. From mid-1916 the hospital trialled the use of a new antiseptic paste, known as BIPP, which proved very successful when used on men sent back to them from the Somme battlefield.

As neither Garrett Anderson nor Murray left direct descendants or private papers it is difficult to get close to them. The image they presented is the one that survives and suggests that both were reserved, with Murray the more resolutely aloof and Garrett Anderson slightly more approachable. These characteristics, while perhaps natural, were also necessary in giving the women the credibility with which to operate such an establishment. Yet it is clear they were greatly appreciated by both staff and patients. Endell Street appears to have been comfortable and sociable, the male patients soon becoming entirely at ease with the idea of being treated by women.

Although it is perhaps difficult to bring the principals to life, Endell Street is characterised by the more personal stories of young women who, travelling from all parts of Britain, Australia, Canada and the US, had the foresight to record their experiences. These are enlivened by the revelations of all-too-human work-centred discontents. The novelists Beatrice Harraden and Elizabeth Robins clearly managed to wring a good deal of drama out of running the hospital library.

Endell Street was decommissioned in the autumn of 1919. During its final year the hospital treated victims of the three waves of the ‘flu pandemic, in February 1919 experiencing more deaths than it had in any month during the war. These deaths included a significant number of staff members.

But, as the author comments, as far as women in medicine were concerned, ‘The war had changed everything, and nothing’. After the war, while some professions were opened up to women for the first time, it was once again made very difficult for women doctors to build a hospital career and young women were again barred from many medical schools. Sadly, after a brief effort, Murray and Garrett Anderson were unable to continue running the hospital for children that they had founded before the war. In the final chapter the author assuages our curiosity and details the ‘afterlives’ of Garrett Anderson and the other women with whom we’ve kept company during the war years in Endell Street.

In the summer of 2017 I very much enjoyed taking part in a a performance of ‘Deeds Not Words’, an immersive drama staged by Digital Drama in the Swiss Church in Endell Street, opposite the site of the hospital. Belief was suspended, and I really felt myself walking through the hospital wards, encountering staff and patients. You can watch a Digital Drama film about the Endell Street hospital here. This is based on some of the material used by Wendy Moore in Endell Street.

See also a post on this website Women and the First World War: the work of women doctors

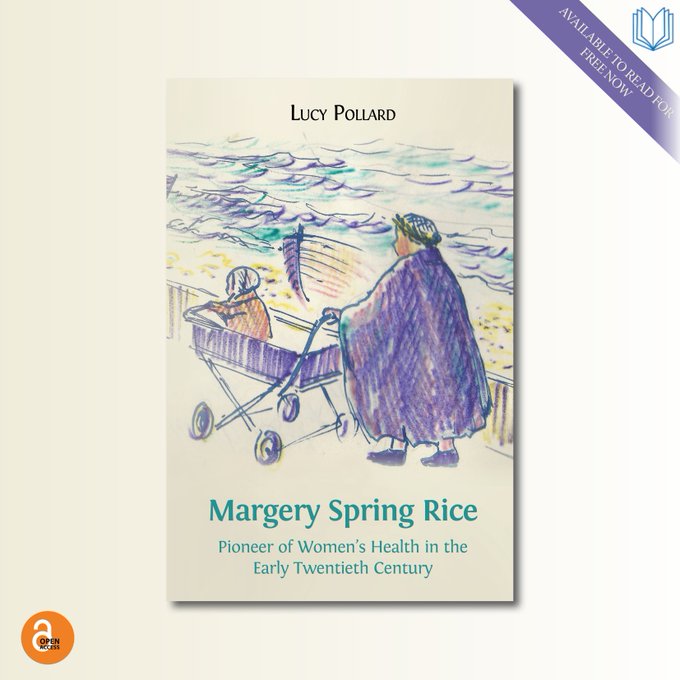

Apparently Louisa Garrett Anderson’s one venture into print, a biography of her mother, was prompted by learning that a cousin, Margery Spring Rice (1887-1970), was considering Elizabeth Garrett Anderson as a suitable subject for just such a work. Now Margery, in her turn, has had her life placed under the spotlight- by Lucy Pollard, a grand-daughter. And what a rewarding subject she is. Here all is drama – love, death, affairs, court cases, divorce, blighted lives – set alongside the achievements of a life spent working to improve the lot of working-class women.

Margery Garrett was the daughter of Sam Garrett, a favourite brother of Elizabeth and Millicent. He seems to have been easy going; his daughter was rather more volatile. She was educated at Girton, married in 1911 and had three children before her husband was killed on the Somme in 1916. A disastrous second marriage produced two more children. Equipped with an abundance of energy Margery Spring Rice, as she now was, chanced on the cause of birth control as the subject of her life’s work. This was a subject shunned by the medical profession but one which she recognised as an imperative if poor women were to retain their health and any ability to care properly for the children they did bear.

In 1924, with two friends, she founded a ‘contraception clinic’ in north Kensington, a notoriously impoverished area, retiring only in 1957. It proved very successful with Margery ‘wholeheartedly encouraging and supporting the liberal attitude prevalent among its staff’. In 1939 she wrote Working-Class Wives: their health and conditions (Penguin) which has become a classic, re-published by Virago in 1981.

Margery Spring Rice is a delight to read. Well-written and impeccably referenced, this is no hagiography, Lucy Pollard making clear that Margery Spring Rice was a difficult woman ‘not much given to self-reflection or self-doubt’, ‘full of contradictions’, and, to my mind, all the more interesting for it. She spent much of her life in Suffolk and for a time was close to Benjamin Britten, although, rather poignantly did find herself dropped in later years. I love the cover illustration showing ‘Margery pushing a young friend along the Crag Path in Aldeburgh, New Year 1968’ (Christopher Ellis).

Wendy Moore, Endell Street: the trailblazing women who ran World War One’s most remarkable military hospital, Atlantic Books, 2020, £17.99.

Lucy Pollard, Margery Spring Rice: pioneer of women’s health in the early twentieth century, Open Books Publishers, 2020.

Free download: https://www.openbookpublishers.com//download/book/1204

Hardback: £29.95

Paperback: £19.95

For full details see here

Copyright

The Garretts And Their Circle: Fanny Wilkinson And Middlethorpe Hall

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on July 9, 2018

Middlethorpe Hall, York

As part of Bloom! – a festival celebrating horticulture and flowers in York – I was invited give a talk yesterday about Fanny Wilkinson, Britain’s first professional woman landscape gardener, in Middlethorpe Hall, the home of her youth.

Middlethorpe Hall, now owned by the National Trust and run by the Historic House Hotels, is utterly lovely – from its panelled interiors, delicious food, kind staff – to its interesting and well-kept – and extensive – grounds. It retains an appealingly domestic atmosphere and it wasn’t difficult to think of Fanny Wilkinson living there in the 1880s with her mother and sisters.

Yet Fanny was not content with being a ‘daughter-at-home’ and enjoying these beautiful surroundings (although letters show she was delighted to return to Middlethorpe for short breaks) and it was while living here that she developed the ambition of becoming a landscape gardener. Wasting no time, she set off for London and enrolled at the Crystal Palace School of Gardening, run by Edward Milner who had been a pupil of Joseph Paxton. She was the only woman student- and an upper-middle class woman at that. All the others were male artisans – for whom the School was intended.

If you are interested in discovering just how many of London’s open spaces were designed by this one determined woman, you can read all about Fanny Wilkinson’s extremely successful career – and discover how it was intertwined with those of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Millicent Fawcett and Agnes Garrett, in Enterprising Women:the Garretts and their circle see https://francisboutle.co.uk/products/enterprising-women/

Copyright

The Garretts And Their Circle: What Should The Practical Medical Student Wear?

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on January 7, 2018

Millais: ‘Trust Me’

As she embarked on her novel medical career Elizabeth Garrett gave some thought as to how she should dress. In September 1860, while working as a nurse at the Middlesex Hospital, she wrote to Emily Davies:

‘Experience is modifying my notions about the most suitable style of dress for me to wear at the hospital. I feel confident now that one is helped rather than hindered by being as much like a lady as lies in one’s power. When my student life begins, I shall try to get very serviceable, rich, whole-coloured dressed that will do without trimmings and not require renewing often.’

Three years later, still trying to piece together her medical training, she spent the autumn of 1863 fulfilling the ‘clinical practice’ requirement for the London Society of Apothecaries’ qualification, by attending clinics at the London Dispensary in Spitalfields. As Jo Manton writes in her biography of Elizabeth, the London Dispensary was ‘charity at its bleakest’, 2000 outpatients from the surrounding slums passing through its doors each year. Thanks to the following brief comment in a letter to Harriet Cook, 23 December 1863, we, too, can picture Elizabeth Garrett as she travelled through sordid Whitechapel from her lodgings at 8 Philpot Street and then helped to treat patients in the Dispensary at 21 Church Street, Spitalfields (now 27 Fournier Street). Had she seen the Millais painting and thought ‘That is just the effect a tyro female doctor must create’?

’ I think your critical eyes would be satisfied if they could see me in my working dress. I was fortunate enough to find a delightful gown of bright pre-Raphaelite brown which has stood 9 weeks of hard and constant wear without losing its colour or freshness of look. So you can fancy me in it. The colour resembles that in Millais’ “Trust Me” tho’ the material is less magnificent than that was.’

27 Fournier Street, Spitalfields, formerly the London Dispensary

Copyright

The Garretts And Their Circle: A Talk At The Royal Society of Medicine To Celebrate The 150th Anniversary of Elizabeth Garrett’s Qualification As A Doctor

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on January 19, 2016

On 28 September 1865 Elizabeth Garrett succeded in qualifying as a doctor and as such is hailed as the first woman in Britain to do so. That is, she was first woman qua woman (ie not, as Miranda Barry, in the guise of a man) and she was the first woman to gain British medical qualifications (ie not, as her mentor Elizabeth Blackwell, by qualifying in the US).

To celebrate this auspicious event I was asked, along with Professor Neil McIntyre, to gave a talk at the Royal Society of Medicine. That there is still a great deal of interest in Elizabeth Garrett and her fellow pioneers was evident as we surveyed the packed house.

The video of my talk, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her Hospital, is now available to view here. Professor McIntyre’s talk, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her Medical Schools, can be viewed here.

For those interested in learning more about Elizabeth Garrett’s medical career do visit the ‘Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery at the UNISON Centre – for more details see here.

You might also be interested in reading my book – Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle – for details see here.

Copyright

Caroline Crommelin and Florence Goring Thomas: 19thc Interior Decorators: Who Were They?

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle, Uncategorized on May 26, 2015

Caroline Anna de Cherois Crommelin (c 1854-1910) was born in Co Down, Ireland, one of the many children of Samuel de la Cherois Crommelin of Carrowdore Castle.

Although of gentle birth, the family had little money. Political unrest in Ulster forced a move to England and after their father’s death in 1885 Caroline Crommelin and her sisters found it necessary to work to support themselves.

Caroline’s elder sister, May, became a novelist and enjoyed a measure of popular success. In 1903 another sister, Constance, married John Masefield (who was very much her junior).

In 1886 another of the sisters, Florence, married a solicitor, Rhys Goring Thomas, and in the late 1880s with Caroline, who seems to have been the driving force, embarked on a career as a ‘lady decorator’. The pair were able to travel easily along the path blazed for them a decade earlier by Rhoda and Agnes Garrett.

Unlike the Garretts, Caroline and Florence do not appear to have had any specific training, although years later Caroline wrote that an apprenticeship was essential. Rather, they relied on what was assumed to be a natural taste absorbed from their early surroundings. In a later interview Caroline described how their father had given the two of them a room in Carrowdore Castle to do with as they wished and from painting and papering this room they had learned their trade. Whereas Rhoda and Agnes Garrett were happy to deal with drains and internal structures, I doubt that such practicalities fell within the Crommelin sisters’ remit.

It was ‘beautifying’ that was the word most often used to describe Caroline Crommelin’s work. An article by Mary Frances Billington in The Woman’s World, 1890, describes how in 1888 Caroline Crommelin set up a depot at 12 Buckingham Palace Road for the ‘sale of distressed Irish ladies’ work’ and then ‘saw a wider market as a house-decorator, so she wrote ‘Art at Home’ on her door-plate, took into partnership her sister, Mrs Goring Thomas..and boldly set forth to hunt for old oak, rare Chippendale, beautiful Sheraton and Louis Seize furniture’. She attended auctions in all parts of the country and, in case there was any doubt as to the propriety of this involvement with trade, reported that she had no difficulty doing business with dealers, meeting only with civility.

Noting the popularity of old, carved oak, the sisters’ bought old plain oak pieces and then had them carved by their own craftsmen. There was always a stock of such pieces in their showroom.

The ‘Arts at Home Premises’ were opened in Victoria Street, London, in early 1891. I think their house was at 167a Victoria Street – certainly by 1898 this was Caroline Crommelin’s work premises, but it’s possible that in the late 1880s she was working from 143 Victoria Street. Of the ‘Arts at Home’ premises The Sheffield Telegraph (9 March 1891) described how’charmingly arranged rooms, stored with delightful old oak, Sheraton, and Chippendale furniture, quaint brass ornaments, old silver, beautiful tapestries, and old china were crowded all afternoon with the many friends of the clever hostesses.’..The oak room featured a delightful ‘cosy corner’ in dark oak with blue china arranged on the top ledge against the pink walls. May Billington’s article includes a line-drawing of a corner of the ‘Arts at Home’ showroom.

In its 23 November 1895 issue the York Herald commented of Caroline Crommelin that ‘Her house in Victoria St is conspicuous to the passer by for the pretty arrangement of its curtains, and inside the artistic element is even more apparent. Miss Crommelin has been very successful as a house beautifier and her opinion has been much sought after and esteemed by those who like the home to be dainty and harmonious.’

In 1891 the sisters also displayed their wares at the Women’s Handicrafts Exhibition at Westminster Town Hall. The Manchester Times singled them (‘two of our cleverest art decorators’) out for praise. ‘These ladies have shown that… old oak furniture need not be gloomy and dusty and that new furniture may be made to look as good as old, even if the old be Chippendale or Sheraton, Queen Anne or Dutch marqueterie.’

One of Caroline Crommelin’s first ‘beautifying’ commissions was carried out for Lord and Lady Dufferin on the British Embassy in Rome in 1890/1891. The Manchester Guardian (8 Oct 1889) reported that she redecorated the entire embassy. Doubtless this plum commission was not unconnected to the fact that the Dufferin estate in Co Down was a mere 10 miles from Carrowdore Castle; the families were presumably known to each other. Rather more surprising is the claim made in an interview with her in the Women’s Penny Paper, 23 Nov 1889, that she had ‘supplied nearly all the furniture to Lord Cholmondeley’s old place at Houton [sic]. Houghton Hall was let to tenants during the 19th century so, perhaps, there is a kernel of truth buried in this statement – but I don’t think we need go looking at Houghton as it is today for evidence of Caroline Crommelin’s involvement in its decoration.

In interviews Caroline Crommelin also made clear that she ‘undertakes, when required, to furnish a whole or any part of a house, either going with the customer to different firms or selecting for them’ and ‘does not confine herself to decorative work alone, and will put up blinds or attend to the whitewashing of a ceiling with the most professional alacrity’.

Both Caroline and Florence were supporters of the campaign to give the vote to women householders and were keen to see women’s advancements in the professions – particularly as architects.

In 1895 Caroline Crommelin married Robert Barton Shaw, nephew of a former Recorder of Dublin, who in the 1901 census return is described as an estate agent. I wonder if his wife helped in ‘beautifying’ houses he had for sale? In 1901 they were living at 50 Morpeth Mansions, Morpeth Terrace. Caroline in this census return is described as an ’employer’. Florence lived close by -in 1891 at 3 Morpeth Terrace. However hers was to be a short-lived career – she died in 1895, aged only 37, a few months before her sister’s marriage. In the 1889 Penny Paper interview Florence was quoted as saying ‘I believe everybody is happier for working. It carries one into a new life, and one does not have time to think of being ill’. In the light of her early death this has a certain poignancy, suggesting she may have had a chronic illness to overcome.

Caroline carried on the business on her own and in 1903 teamed up with her sister, May, to write a chapter on ‘Furniture and Decoration’ in Some Arts and Crafts (ed Ethel Mckenna), published in The Woman’s Library series by Chapman & Hall. In this they ran through the various periods of furniture and room design but did not bother to disguise their support for one style in particular. ‘Anyone of artistic feeling is sensible of a singular sense of well-being on entering a genuine Queen Anne sitting-room. If analysed, the sensation will be found to arise from an instantaneous inner perception that all is in just proportion. The height and size of the room obey accurate laws. Its ceiling is relieved by geometrical designs. The walls are half-wainscoted; the polished floor shows up the tapestry-like carpet in the centre. The ornaments of furniture and general decoration are neither profuse, grotesque, nor severe. In all, the fatal “too much” is avoided.’

Caroline Crommelin (or, rather, Mrs Barton Shaw) died at 18 Albion Place, Ramsgate on 1 February 1910.

Copyright

Mrs Hartley Brown And Miss Townshend -19th-c Interior Decorators: Who Were They?

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on February 27, 2015

In a chapter on ‘Decorative Art in England (Travels in South Kensington, 1882) Moncure Conway commended Rhoda and Agnes Garrett for their ‘admirable treatment of the new female colleges connected with English Universities’. It has always been a niggle that neither I – or anyone else – as far as I know – has ever been able to find any evidence that the Garretts did work on the interior of any women’s college.

In a chapter on ‘Decorative Art in England (Travels in South Kensington, 1882) Moncure Conway commended Rhoda and Agnes Garrett for their ‘admirable treatment of the new female colleges connected with English Universities’. It has always been a niggle that neither I – or anyone else – as far as I know – has ever been able to find any evidence that the Garretts did work on the interior of any women’s college.

As one member of the Garrett family, Elizabeth, was a close friend and supporter of Emily Davies, founder of Girton, another, Millicent, was a founder of Newnham, and Rhoda and Agnes had received their training in the office of J.M. Brydon, sharing an office with Newnham’s architect, Basil Champneys, it would not have been at all surprising if they had been involved with the interior decoration of one or other of the colleges. But neither in Garrett family letters nor in the press is there any mention of Rhoda and Agnes working on the interior of Newnham – or of Girton.

Merton Hall, Cambridge. (Photo courtesy of Cambridge 2000)

Merton Hall, Cambridge. (Photo courtesy of Cambridge 2000)In fact the only mention of work being done by women interior decorators on a Cambridge women’s college relates to furnishings for an early incarnation of Newnham – when, between October 1871 and 1874, it was housed in an ancient, rambling house, Merton Hall. The house belonged (and still belongs) to St John’s College, whose Master was very sympathetic to the Lectures for Ladies’ scheme that had been instigated in Cambridge by Millicent Fawcett, Henry Sidgwick and Jemima Anne Clough.

Merton Hall is first mentioned by Moncure Conway in ‘Decorative Art and Architecture in England’, an article published in Harpers New Monthly Magazine, November 1874. In this, after discussing the work of Rhoda and Agnes Garrett, he tells us that Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend had set up in the same business as the Garretts, in premises at 12 Bulstrode Street. He then goes on to say that ‘These ladies, who have been employed to decorate the new ladies’ College (Merton) at Cambridge, have not only devised new stuffs for chairs, sofas and wall panels, but also for ladies’ dresses.’ The fact that he uses the past tense seems to indicate that the work was already complete.

A further allusion to this partnership is made by Emily Faithfull when discussing new trade opportunities that have been opening for women. In Three Visits to America (1884) she mentions that ‘Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend, soon after entering into partnership, were appropriately employed in decorating Merton College, and devised with much success some new stuffs for the chairs and sofas for the use of Cambridge girl graduates.’

That seems quite clear: Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend had been involved with furnishing Merton Hall (later Newnham) and neither Conway or Faithfull, although discussing the Garretts’ work, made any mention of the Garrtts being similarly employed.

However, when Moncure Conway came to publish Travels in South Kensington in 1882 the Garretts were going from strength to strength and, if the silence in the press is anything to go by, Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend had gone out of business. One construction might be that, while making no mention of the latter two, Conway lauds the success of the Garretts and, carelessly assigns to them the ‘admirable treatment of female Colleges’. It may be that only one firm of female interior decorators worked on the furnishings of a female college – and that was the partnership of Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend.

But who were Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend? I have to confess to drawing a blank on Mrs Hartley Brown – but can make an educated guess at the identity of Miss Townshend.

In his Harper’s 1874 article Conway (who, as we see was prone to getting things a bit muddled) mistakenly describes Mrs Hartley Brown as ‘a sister of Chambray Brown, Esq – a very distinguished architect’. In fact what he meant was that ‘Miss Townshend was a sister of Chambray Townshend…’. The latter was indeed an architect, although not even his wife – indeed particularly not his wife – would have called him distinguished. Unfortunately for us Chambray Townshend had eight sisters. And the question is ‘which one went into business as an interior decorator?’

Well three can be discounted, being in 1874 already married. Of the remaining five, very little is known of the lives of three, although Alicia, who didn’t marry until 1880, is known to have studied art at the Slade and is I suppose a possibility. However I suspect that the two strongest candidates of the five are Isabella (1847-1882) and Anne (1842-1929).

Anne certainly seems to have the most productive work record. According to family information she trained as a nurse at London’s Foundling Hospital and was later Matron at the Hospital for Hip Disease in Childhood (Queen’s Square). When and for how long she was engaged in nursing I don’t know. By 1882 she had moved into philanthropic administration and was secretary of the Metropolitan Association for Befriending Young Servants (MABYs).

Then in 1888 she became the first secretary of the Ladies’ Residential Chambers Co (the founders of which included Agnes Garrett and Millicent Fawcett) and remained involved with the company until 1910. In 1890, when the company was planning a new set of chambers in York Street, Marylebone, it was Anne Townshend who was deputed to consult with Thackeray Turner, the architect, over the company’s specifications for the new building. However nowhere in the minutes of the Ladies’ Residential Co is there any suggestion that she was ever involved with the interior design of either of the buildings.

Isabella Townshend is the more artistic candidate – and she does have a very clear Cambridge connection- being one of the Girton Pioneers. In 1869 she was one of the first five to join Emily Davies at her new college at Hitchin (it was not yet ‘Girton’). She left without taking a Tripos at Easter 1872. Could she then have gone into the interior decorating business?

In Girton College, Barbara Stephen comments that ‘Miss Townshend was not striking in either appearance or manner‘, while reporting Barbara Bodichon’s opinion that [Isabella’s] ‘interests were wide and her mind original’ Barbara Stephen was too young ever to have met Isabella; perhaps she made her rather harsh judgement on the basis of this photograph she included in her book

However, Isabella certainly made a very strong impression on her fellow Pioneers – particularly on Emily Gibson. When Isabella left Hitchin in the 1872 without taking a Tripos (perhaps it was this high-handed approach to all that Miss Davies had to offer that attracted Barbara Stephen’s disapproval) Emily followed suit and the following year married Isabella’s brother, Chambray Townshend.

However, Isabella certainly made a very strong impression on her fellow Pioneers – particularly on Emily Gibson. When Isabella left Hitchin in the 1872 without taking a Tripos (perhaps it was this high-handed approach to all that Miss Davies had to offer that attracted Barbara Stephen’s disapproval) Emily followed suit and the following year married Isabella’s brother, Chambray Townshend.

In Some Memories for Her Friends., Emily wrote of Isabella: ‘She was more mature than many of us, and in quite a different stage of development, but the sort of position she held among us, the sort of influence she exercised over me was chiefly due to her having been swept over by a very early wave of that current of aestheticism which was then just beginning to gather force. The sort of doctrine she taught, or rather that she gave living expression to, was, that the most valuable means of culture was to be found in the enjoyment of the beautiful in nature and art, that a beautiful combination of colours, a delicate bit of decorative work seen and cared for in a reverent and appreciative spirit, could do more for us in the way of training and development than much steady grinding away at mathematics and classics.’

‘She had considerable ability, indeed, many of us gave her credit for a touch of genius, yet she never accomplished much definite work of any kind.’..Isabel took the utmost pains to live from hand to mouth. She would work hard now and again when she felt the subject in hand to be worth working at, but she scorned to tie herself down to do things against inclination for the sake of obtaining some definite mundane good.’

Isabella Townshend, self-portrait, (c) Girton College, University of Cambridge. Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Isabella Townshend, self-portrait, (c) Girton College, University of Cambridge. Supplied by The Public Catalogue FoundationIsabella Townshend was undoubtedly ‘artistic’. Isn’t this a wonderful self-portrait – bequeathed to Girton by Emily Townshend? It wouldn’t at all surprise me if Isabella had not ‘devised new stuff’ for her dress and designed it herself. But did she have the stamina to set up in business? Emily Gibson mentions that in the period between leaving Cambridge and her marriage to Chambray Townshend, he and Isabella were particularly friendly with Walter and Lucy Crane – so she was certainly moving in art design circles.

There is no doubt that interior decorating ran in the family veins. In his Harper’s article Moncure Conway wrote ‘I have become convinced by a visit to a beautiful house which Chambrey Townshend arranged at Wimbledon, that there can be nothing so suitable for somewhat dark corridors and staircases as a faint rose tint. In Mr Townshend’s house, however cold and cheerless the day may be, there is always a glow of morning light. This gentleman has shown that a sage-gray paper with simple small squares (such as Messrs Marshall & Morris make) furnishes a good dado to support the light tints upon walls not papered.’

The house may well have been the Townshend family home at 12 Ridgway Place, Wimbledon, where the unmarried sisters lived with their mother.

Unfortunately Chambray Townshend took the same laissez-faire approach to work as did Isabella. Of him Emily, his wife, later wrote ‘Chambrey Townshend had little push and no business ability to back up his remarkable artistic abilities.’ After his death she regretted she hadn’t devised some opening for his remarkable talent for house decoration ‘when architectural work was not forthcoming’.

If the interior decoration business was run by Mrs Hartley Brown and Isabella Townshend, it may be that Isabella soon lost interest. In the early 1880s she went to Italy to study painting and died in 1882. The Girton Register has it that she died in Italy, ‘of typhoid fever contracted at Capri’. It may well be that she became ill in Italy, but the Probate Register shows that she died on 20 July 1882 at Ealing and was buried at Perivale on 25 July 1882.

So, although Anne Townsend had the stamina and application to run a business, I’m inclined to think that it was Isabella Townshend who, for a brief period, was in partnership as an interior decorator with Mrs Hartley Brown and who provided the furnishings for Merton Hall, the early incarnation of Newnham.

For more about the interior decoration business run by Rhoda and Agnes Garrett see here.

**

The Garretts And Their Circle: Annie Swynnerton’s ‘Crossing The Stream’

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on July 24, 2013

‘Crossing the Stream’ by Annie Swynnerton. Manchester City Art Gallery Collection. Photo courtesy of MCAG and ArtUK

Another of Annie Swynnerton’s paintings left to Manchester City Art Gallery by Louisa Garrett.

The way in which the Garrett circle did their best to ensure that Annie Swynnerton’s work was included in major public collections is discussed in my book – Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle- available online from me, or Francis Boutle Publishers or from all good bookshops.

The Garretts And Their Circle: Annie Swynnerton’s ‘The Town of Siena’

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on July 23, 2013

‘The Town of Siena’ by Annie Swynnerton, Manchester City Art Gallery Collection, photo courtesy of MCAG, BBC Your Paintings and ArtUK

This is another of Annie Swynnerton’s paintings left to Manchester City Art Gallery by Louisa Garrett.

The way in which the Garrett circle did their best to ensure that Annie Swynnerton’s work was included in major public collections is discussed in my book – Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle- available online from me, or Francis Boutle Publishers or from all good bookshops..

The Garretts And Their Circle: Annie Swynnerton’s ‘Illusions’

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on July 22, 2013

‘Illusions’ by Annie Swynnerton, Collection Manchester City Galleries, courtesy of BBC Your Paintings & ArtUK

This painting was left to the City Art Gallery, Manchester, by Louisa Garrett (nee Wilkinson, sister-in-law to Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Millicent Fawcett and Agnes Garrett.

‘Illusions’ would once have hung in Louisa’s home at Snape in Suffolk. Her house was named ‘Greenheys’ after the area of Manchester in which she and her sister, Fanny, grew up.

The way in which the Garrett circle did their best to ensure that Annie Swynnerton’s work was included in major public collections is discussed in my book – Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle- available online from me, or Francis Boutle Publishers or from all good bookshops..

The Garretts and Their Circle: Annie Swynnerton’s ‘The Dreamer’

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on July 19, 2013

The Dreamer by Annie Swynnerton, 1887. (c) Manchester City Gallery – image courtesy of BBC Paintings and ArtUK

In yesterday’s post I drew attention to Annie Swynnerton’s portrait of Millicent Fawcett. It was hardly chance that brought that artist and that sitter together; both were central figures in what I term ‘the Garrett circle’.

Today’s painting by Annie Swynnerton, The Dreamer, was originally owned by Millicent Fawcett’s sister-in-law, Louisa Garrett (nee Wilkinson) who for a while lived next-door-but-one to Millicent Fawcett and Agnes Garrett in Gower Street (the latter at no 2 and the Wilkinsons at no 6). The Dreamer was owned jointly by Louisa and her sister, Fanny, and may for a time have graced the walls of 6 Gower Street. Louisa only moved out of no 6 on her marriage to Millicent and Agnes’ youngest brother, George Garrett.

Fanny Wilkinson and Louisa Garrett did all in their power to ensure that, after their deaths, Annie Swynnerton was represented in public collections. In her will Louisa specifically left her share in this painting to Fanny and expressed ‘the desire that she will bequeath the said picture to the City Art Gallery, Manchester.’

Discover much more about the way in which the Garrett circle did their best to ensure Annie Swynnerton’s continuing reputation in my Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle- available online from me, or Francis Boutle Publishers or from all good bookshops..

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery At The UNISON Centre

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on March 28, 2013

ALAS, IT WOULD APPEAR THAT THE GALLERY HAS FAILED TO REOPEN AFTER COVID CLOSURE. PLEASE PHONE UNISON TO ENQUIRE.

The Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery at the UNISON Centre tells the story of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, of the hospital she built, and of women’s struggle to achieve equality in the field of medicine.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) was determined to do something worthwhile with her life. In 1865 she qualified as a doctor. This was a landmark achievement. She was the first woman to overcome the obstacles created by the medical establishment to ensure it remained the preserve of men.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson then helped other women into the medical profession, founding the New Hospital for Women where women patients were treated only by women doctors.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, by her example, demonstrated that a woman could be a wife and mother as well as having a professional career.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson worked to achieve equality for women, being especially active in the campaigns for higher education and ‘votes for women’.

In the early 1890s the New Hospital for Women (later renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital) was built on the Euston Road and continued to treat women until 2000. For some years this building then lay derelict until a campaign by ‘EGA for Women’ won it listed status. UNISON has now carefully restored the building, bringing it back to life as part of the UNISON Centre.

Two important rooms in the original 1890 hospital building have been dedicated to the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery. One is the

ORIGINAL ENTRANCE HALL

of the hospital which has been carefully restored to its original form. Here you can study an album, compiled specially for the Gallery, telling the history of the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in words and pictures, while, in the background you can listen to a soundscape evocative of hospital life. This is interwoven with the reminiscences of hospital patients, snippets from the letters of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and sundry other sounds to stimulate your imagination.

The other Gallery room is what was known when the hospital opened as

THE MEDICAL INSTITUTE

This was a room, running along the front of the hospital, parallel to Euston Road, set aside for all women doctors, from all over the country, at a time when they were still barred from the British Medical Association. It was intended as a space in which they could meet, talk and keep up with the medical journals.

Here you can use a variety of media to follow the story of women, work and co-operation in the 19th and 20th centuries.

A BACK-LIT GRAPHIC LECTERN RUNS AROUND THE MAIN GALLERY:

allowing you to see in words and pictures a quick overview of the life of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and of her hospital.

AT INTERVALS ARE SET SIX INTERACTIVE TOUCH-SCREEN MONITORS

-named – Ambition, Perseverance, Leadership, Equality, Power in Numbers and Making Our Voices Heard – allowing you to access more information about Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, about the social and political conditions that have shaped her world and ours, and about the building’s new occupant – UNISON..

Each monitor contains:

TWO SHORT VIDEO SEGMENTS.

‘Elizabeth’s Story’. Follow the video from screen to screen. Often speaking her own words, the video uses images and voices to tell the story of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson’s life.

‘UNISON Now’ UNISON members tell you what the union means to them.

and four

INTERACTIVES

‘Campaigns for Justice’ and ‘Changing Lives’.

Touch the screen icons to discover how life in Britain has changed since the birth of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson.

AMBITION

Campaigns for justice

Victorian Britain: a society in flux

Victorian democracy: who could vote, and who couldn’t

Did a woman have rights?

Workers organised

Changing lives

The people’s lives in Victorian Britain

The medical profession before Elizabeth Garrett

Restricted lives, big ambitions: middle-class women in the Victorian era

Women workers in the first half of the 19th century

PERSEVERANCE

Campaigns for justice

The changing political landscape

Widening the franchise: can we trust the workers?

Women want to vote: the beginnings of a movement

Trade unions become trade unions

Changing lives

A new concept of active government: Victorian social reform

Women as nurses and carers

Living a life that’s never been lived before: women attempt to enter medicine

International pioneers: women study medicine abroad

LEADERSHIP

Campaigns for justice

Contagious Diseases Acts

Trade unions broaden their vision

Women and education

Women trade unionists

Changing lives

The middle-class century

Working women in the second half of the 19th century

Social reform, philanthropy and paternalism

Women doctors for India

EQUALITY

Campaigns for justice

The women’s suffrage movement

The Taff Vale decision hampers the unions

The founding of the Labour party

The People’s Budget

Changing lives

Work and play

Marylebone and Somers Town

Did the working classes want a welfare state?

1901 – Who were the workers in the NewHospital for Women?

POWER IN NUMBERS

Campaigns for justice