I wrote the following article back in 2006 and it was published in that July’s issue of Ancestors, a magazine published by The National Archives but now, alas, defunct.

The Work of Women Doctors in First World War

On 15 September 1914, six weeks after the outbreak of the First World War, Louisa Garrett Anderson, daughter of Britain’s first woman doctor, wrote to her mother, ‘This is just what you would have done at my age. I hope I shall be able to do it half as well as you would have done’. Louisa was writing in the train on her way to Paris where, with her companion, Dr Flora Murray, she proposed to set up a hospital to treat the war wounded.

Louisa Garrett Anderson (r) and Flora Murray – plus dog. (Phot0 courtesy of BBC website)

Neither woman had any previous experience of tending male patients. Louisa was a surgeon in the New Hospital for Women, founded by her mother, and Flora was physician to the Women’s Hospital for Children that she and Louisa had established in London, in the Harrow Road. Although it was now nearly 40 years since British women had become eligible to study and practise medicine, they were still barred from posts in most general hospitals. Their work was confined to general practice and to the hospitals that had been founded by women to treat women and children. The war, however, created new conditions and by its close around one-fifth of Britain’s women doctors had undertaken medical war work, both at home and, more particularly, abroad.

This experience was not at first gained through the conventional conduit of the Royal Army Medical Corps or through the joint committee of the British Red Cross Society and the Order of St John that had been formed to co-ordinate voluntary medical work. The War Office, believing it had sufficient reserves of male medical personnel, refused to employ women doctors in war zones. However in the chaos of war the relief of suffering was open to any groups – even groups of women – able to raise the necessary funds and staff.

In autumn 1914 British agencies, such as the Serbian Relief Fund, the Society of Friends, the Wounded Allies Relief Committee and the British Farmers, quickly organized medical teams for service overseas. Many of these, such as the Berry Mission and the Almeric Paget Massage Corps, were happy to include women doctors. Of other ‘free enterprises’ the Women’s Imperial Service League, the Women’s Hospital Corps, and the Scottish Women’s Hospitals employed only women doctors.

Mrs Stobart (centre) with her group in Antwerp. Sept 1914. Photo courtesy of Imperial War Museum Collection

The Women’s Imperial Service League was formed by Mrs Mabel St Clair Stobart in August 1914. Unlike most women of her day Mrs Stobart already had experience of organizing a medical mission to a war zone. In 1912 she had founded the Women’s Convoy Corps, taking it to Bulgaria during the first Balkan war. Mrs Stobart’s team had comprised three women doctors, ‘for the purpose of fully demonstrating my argument that women are capable of undertaking all work in connection with the sick and wounded in warfare.’ Similarly, at the invitation of the Belgian Croix Rouge, on 22 September 1914 she took the Women’s Imperial Service League unit to Antwerp.

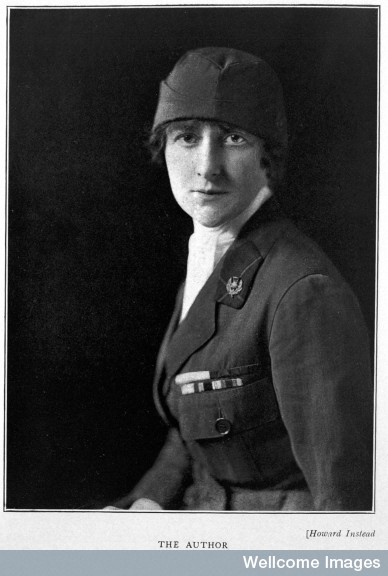

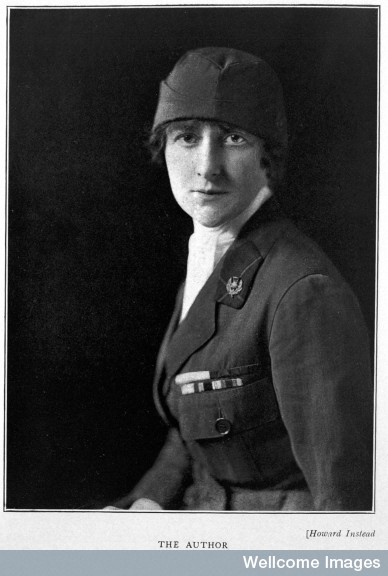

Florence Stoney, wearing the decorations she received for her service during the First World War

The doctor-in-charge was Dr Florence Stoney, who before the war had set up the x-ray department at the Royal Free and the New Hospital for Women and who brought with her the very latest in x-ray equipment. Accompanying her were five other women, Drs Joan Watts, Helen Hanson, Mabel Ramsay (for her account of the expedition click here) , Rose Turner and Emily Morris. As the Germans overran Belgium the women were quickly forced to evacuate.

In April 1915, after working for a time in France, the Stobart Unit set out for Serbia, under the auspices of the Serbian Relief Fund. That country had lost many of its own doctors and was grateful for the assistance of the Unit, which by now comprised 15 women doctors. The Unit dealt with those wounded in battle but also played an important part in treating the neglected civilian population. Typhus was a major threat to the health of both soldiers and civilians and the Unit set up roadside dispensaries so that patients could be treated before they entered towns and spread infection further. This work came to an end when Bulgaria invaded Serbia in October 1915 and the Unit was forced to retreat.

George James Rankin, Mrs M. A St Clair Stobart (Lady of the Black Horse. (c) British Red Cross Museum and Archives; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation)

Mrs Stobart, a feminist but fiercely independent, had not been directly involved in the pre-war suffrage campaign, unlike many of her doctors. Drs Helen Hanson and Dorothy Tudor, who went out to Bulgaria with her in 1912, were members of the Women’s Freedom League and Dr Mabel Ramsay had been secretary of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage society in Plymouth. Indeed women doctors, as a class, had been very much involved in the suffrage movement, the greater number being associated with the non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Most women could not afford to jeopardize their livelihood and professional standing by serving a prison term.

As tax payers many doctors were members of the Tax Resistance League, prepared to commit acts of civil disobedience that did not result in imprisonment. Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray were relatively unusual in being supporters of Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union. Indeed in 1912 Louisa Garrett Anderson had joined the hunger strike when imprisoned in Holloway after taking part in a WSPU window-smashing raid. However on the outbreak of war the suffrage campaign was suspended and within eight days women doctors, both suffragettes and suffragists, were planning how best to give practical support to the war effort.

Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray wasted no energy in approaching the War Office. Instead, on 12 August, they called in person at the French Embassy, offering to raise and equip a surgical unit, comprising women doctors and trained nurses, for service in France. Within a week the French Red Cross had accepted this offer. The newly-formed Women’s Hospital Corps quickly raised £2000 and on 17 September 1914 Louisa Garrett Anderson was in Paris, writing that ‘we found Claridge’s Hotel [in which their hospital was to be housed] a gorgeous shell of marble and gilt without heating or crockery or anything practical but by dint of mild ‘militancy’ & unending push things have advanced immensely.’

Working alongside Anderson and Murray were Drs Gertrude Gazdar, Hazel Cuthbert and Grace Judge. On 27 September Louisa wrote to her mother: ‘The cases that come to us are very septic and the wounds are terrible. .. We have fitted up quite a satisfactory small operating theatre in the ‘Ladies Lavatory’ which has tiled floor and walls, good water supply & heating. I bought a simple operating table in Paris and we have arranged gas ring and fish kettles for sterilization…After years of unpopularity over the suffrage it is very exhilarating to be on top of the wave, helped and approved by everyone, except perhaps the English War Office, while all the time we are doing suffrage work – or woman’s work – in another form…I wish the whole organization for the care of the wounded…could be put into the hands of women. This is not military work. It is merely a matter of organisation, common sense, attention to detail and a determination to avoid unnecessary suffering and loss of life.’

In March 1915, after running a second hospital at Wimeueux, close to heavy fighting, the Women’s Hospital Corps received the accolade from the War Office of being put in charge of a new military hospital in London, housed in the former St Giles Workhouse in Endell Street, Covent Garden.

Endell Street Military Hospital, 1919. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

The hospital staff comprised women only and included 15 doctors, surgeons, ophthalmic surgeons, dental surgeons, an anaesthetist, bacteriological and pathological experts and seven assistant doctors and surgeons, together with a full staff of women assistants. Members of the executive staff were ‘attached’ to the Royal Army Medical Corps, holding equal rank and receiving equal pay with Army doctors, but were not commissioned and did not wear army uniform. Flora Murray’s rank was equivalent to that of a lieutenant-colonel and Louisa Garrett Anderson’s that of a major. For a ‘Woman’s Hour’ podcast about the Endell Street Hospital click here.

The hospital proved particularly successful in gaining the loyalty of its patients. One, Private Crouch, wrote in 1915 to his father in Australia: ‘The management is good, and the surgeons take great interest in and pains with their patients. They will persevere for months with a shattered limb, before amputation, to try to save it…The whole hospital is a triumph for women, and incidentally it is a triumph for suffragettes’. The Endell Street hospital was retained in service until October 1919, longer than many other temporary military hospitals, and in its time treated over 24,000 soldiers as in-patients and nearly the same number of out-patients.

Plaque commemorating the Endell Street Military Hospital (photo courtesy of Plaques of London website)

Louisa Garrett Anderson who, like all the other women surgeons, had had no previous experience of trauma surgery, was particularly interested in the treatment of gunshot wounds. She backed the BIPP treatment (bismuth and iodoform paraffin paste), publishing articles on the subject in the Lancet. Both Murray and Anderson were, in 1917, among the first to be appointed CBE.

Elsie Inglis, 1916

On the very day in August 1914 that Anderson and Murray were offering their assistance at the French Embassy, Elsie Inglis, a Scottish surgeon, proposed to a meeting in Edinburgh of the Scottish Federation of the NUWSS, of which she was secretary, that help should be given to the Red Cross. Matters swiftly progressed until Inglis was able to offer a unit of 100 beds to either the War Office or the Red Cross. After receiving a sharp rebuff, she, too, approached the French Ambassador with an offer to send hospital units to France. A similar proposition was also made to the Serbian authorities.

By 19 November 1914 the first Scottish Women’s Hospital Unit For Foreign Service was in Calais, dealing with an outbreak of typhoid. The doctor in charge was Alice Hutchinson, who in 1912 had been a member of Mrs Stobart’s Women’s Convoy Corps. In fact it was for service in Serbia that this unit had been recruited and, after dealing with the Calais emergency, by spring 1915 it was able to set up a 40-tent hospital at Valjevo, 80 miles from Belgrade.

Scottish Women’s Hospitals Collecting box 1914-1918. Image courtesy of National MuseumsScotland. http://www.nms.ac.uk

On 2 December 1914 the SWH’s first French unit (that is, the first intended for France) left Waverley Station, bound for Royaumont, where it was to be housed in a 13th-century Abbey.

Norah Neilson-Gray. The Scottish Women’s Hospital : In The Cloister of the Abbaye at Royaumont. Dr. Frances Ivens inspecting a French patient. Picture courtesy Imperial War Museum Women’s Work Section

The unit comprised seven doctors, under the charge of Dr Frances Ivens. It was one of the hospitals closest to the front line and at its peak was, with 600 beds, the largest British voluntary hospital in France. On 25 September 1915 Miss M. Starr, a VAD at Royaumont, wrote of a casualty that had just arrived, ’One arm will simply have to be amputated, he had had poison gas, as well, and the smell was enough to knock one down, bits of bone sticking out and all gangrene. It will be marvellous if Miss Ivens saves it, but she is going to try it appears, as it is his right arm. He went to X-ray, then to Theatre, and I believe the operation was rather wonderful, but I had no time to stop and see’. Four days later she wrote, ‘The operating theatre is a horrible hell these days, it goes on till 2 and 3 in the morning. Then there is another fitted up temporarily on one of the Ward kitchens’.

In mid-1917 Royaumont opened a satellite camp hospital even closer to the line, at Villers Cotterets. From there in May 1918 Dr Elizabeth Courtauld wrote, ‘Terrible cases came in. Between 10.30 and 3.30 or 4 am we had to amputate six thighs and one leg, mostly by the light of bits of candle, held by the orderlies, and as for me giving the anaesthetic, I did it more or less in the dark at my end of the patient’.

Between January 1915 and February 1919 the surgeons at Royaumont and Villers Cotterets performed 7204 operations. The hospital had an excellent x-ray unit, necessary for locating bullets and shrapnel before surgery, and placed great importance on bacteriological examinations. To prevent death from gas gangrene the doctors followed the procedure developed in 1915 of extensive excision of the wound, which was then kept open, with an appropriate dressing, for later suture.

In May 1915 a second Scottish Women’s hospital was established by the ‘Girton and Newnham’ Unit, in tents, near Troyes. Its doctors included Laura Sandeman, Louise McIlroy and Isabel Emslie.

In November 1915 the unit was moved from France to Salonika, attached to the French Expeditionary Force. By April 1915 Elsie Inglis was in Serbia, in charge of another unit, the ‘London’. She worked there and in Russia until the autumn of 1917 when, with her unit, she returned, mortally ill, dying the day after arriving at Newcastle.

In Serbia the necessity was less for war surgery than for combating disease. Dysentery, typhus and malaria were rife. The SWH laboratory attached to the Girton and Newnham Unit was the best equipped in Serbia and its pathologists were kept busy. In it Isabel Emslie carried out cerebro-spinal fluid examinations for the consultant physician to the British Army, writing later, ‘I was proud and most willing to help by giving this voluntary contribution to the British, who had not thought fit to accept our SWHs.’

Girton and Newnham Unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals about to embark on board ship at Liverpool, October 1915. Photo courtesy of Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow Archive

In the summer of 1916 another SWH unit, named the ‘American Unit’ because it was financed by money raised in the USA, was sent to Ostrovo, 85 miles from Salonika. It was to remain in Serbia until mid-1919. Isabel Emslie became its chief medical officer in 1918.

Dr Isabel Emslie. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

She later wrote, ‘I did the operating and was ably assisted by the keen young doctors, latterly arrived from home, who were able to brief me on the latest methods, for it was now four years since I had been home. I undertook major operations which I never imagined would have fallen to my lot, and I would never have had the temerity to tackle all the specialist operations if there had been anyone else capable of doing them. Looking back on a long life of medical work and service, I believe that my sojourn in Vranja was the most worth-while period of my war experience and possibly of my life’. The work of the SWH in Serbia only ended in March 1920, by which time over 60 British women doctors, some of whom were working independently of the SWH, had served in the country.

By 1916 the War Office, recognizing that the supply of male doctors was dwindling, reversed its policy and sent a contingent of 85 medical women to Malta. Others followed and, for the remainder of the war, were to be found working in Egypt, Salonika and the Sinai Desert. These women were attached to the RAMC, receiving 24s a day, the pay of a male temporary officer. However they did not have equal rights, were forced to pay for their own board and were not permitted to wear uniform.

In Britain, again in response to the shortage of male doctors, a few women were appointed to posts in military hospitals. For instance Dr Helena Wright was a surgeon at Bethnal Green Military Hospital and Dr Florence Stoney, following her work with Mrs Stobart’s Unit, was appointed to the x-ray department of the Fulham Military Hospital. In addition, as the war dragged on, new posts became available to women doctors in connection with the new women’s services, the WAAC, the WRNS, and the WRAF.

During the war the necessity of providing the country with doctors forced the medical profession to allow women access to schools previously the preserve of men. The London School of Medicine for Women also played its part, expanding rapidly until, by 1919, it was the largest medical school in the country.

In How to Become a Woman Doctor, published in 1918, the author optimistically wrote that ‘War-time appointments at large hospitals have given great satisfaction and done much to break down old conservative ideas’. However, with the return to peace, the forces of reaction regrouped. The Royal Free once again became the only London teaching hospital offering clinical instruction to women. Women doctors, even those who had gained extensive experience in all aspects of medicine during the previous four years, were relegated to the type of position that they had held before the war. Although doctors such as Louise McIlroy, Frances Ivens and Isabel Elmslie had distinguished post-war careers, these were not based on the practical experience they had gained during the war.

The war-work of women doctors was quickly forgotten. It is only in the last decade or so that detailed research on the subject has been published. This has been facilitated by war diaries and collections of letters donated to archives either by the women medical workers themselves or by their descendants. If you believe that you have in your possession any such material, do consider depositing it at one of the archives listed below.

Taking it further

Imperial War Museum, Lambeth Road, London SE1 6HZ holds books, papers and photographs relating to the work of medical women in the First World War.

The Liddle Collection, Leeds University Library, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT – is a specialist collection of primary material relating to the First World War, including papers of women doctors.

The Wellcome Library, 210 Euston Road, London NW! 2BE holds the archive of the Medical Women’s Federation, which includes some material relating to the work of women doctors in the First World War.

The Women’s Library@ LSE – holds papers relating to Louisa Garrett Anderson, Flora Murray and the Women’s Hospital Corps

Mitchell Library, 201 North Street, Glasgow holds the main archive of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals

Further Reading

Eileen Crofton, The Women of Royaumont: a Scottish women’s hospital on the Western Front (Tuckwell Press, 1997)

Monica Krippner, The Quality of Mercy: women at war, Serbia 1915-18 (David & Charles, 1980)

Leah Leneman, In the Service of Life: the story of Elsie Inglis and the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (Mercat Press, 1994)

Flora Murray, Women as Army Surgeons (Hodder & Stoughton, 1920)

[