Drawing, Sitting Room, 7 Owen’s Row, Islington; Richard Parminter Cuff (British, 1819 – 1883); brush and watercolour and gray wash over graphite; 2007-27-57. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Drawing, Sitting Room, 7 Owen’s Row, Islington; Richard Parminter Cuff (British, 1819 – 1883); brush and watercolour and gray wash over graphite; 2007-27-57. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

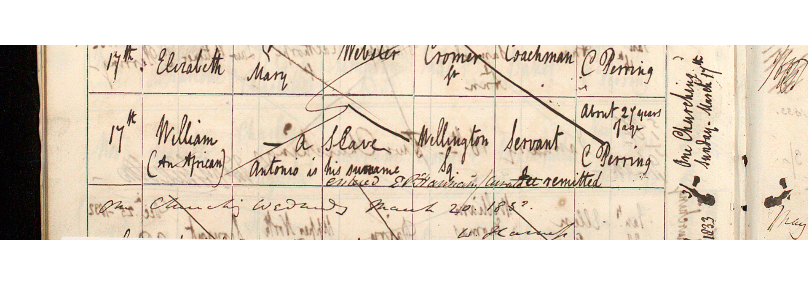

I have a memory of this watercolour coming up for auction in the early 1990s, although I can no longer identify the sale. It caught my attention then because it is showed the interior of a house that once stood next-door-but-one to my own. At that time I was unable to contemplate buying it, even though it was so decorative and apposite, but the memory of it stayed with me and yesterday, now in lock-down, I idly searched the internet and with pleasure found that the image was now in the public domain, part of a Smithsonian collection.

The caption to the water colour gives some information but I thought I would see what I could do to amplify it now that so much material is available on the internet and I have plenty of time to indulge in idle research.

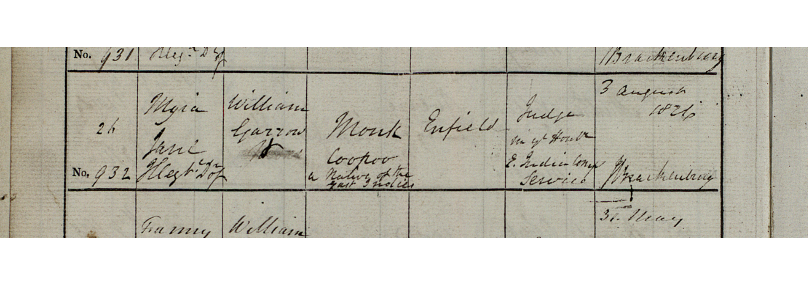

In fact, I was pleasantly surprised how easily I uncovered the reason why the artist had painted the scene. For in the 1851 census I found the artist, Richard Parminter Cuff, living in that house, 7 Owen’s Row in Clerkenwell, a short distance south of the Angel, Islington.

This is the earliest photograph I have found of Owen’s Row, showing it in 1946 after the ravages of war had taken their toll. 7 Owen’s Row is the 5th house from the right, the second in the row of lower houses. Built in 1775, it comprised a basement, ground floor, first floor, second floor and attic, with two rooms to each floor. The photograph shows the damage done to the row during the 1940 Blitz. In fact, by then three houses (numbers 11 to 13) had been demolished – you can see the wooden buttress supporting the end wall of the terrace. To the far left of the photograph had stood Dame Alice Owen’s Girls’ School, opened in 1886.

Dame Alice Owen’s Girls’ School at the beginning of the 20th century. No 7 Owen’s Row will be on the far right of the photo

The basement of the school was being used as a public air raid shelter when, in the evening of 15 October 1940, it received a direct hit. The building collapsed, killing about 150 people.

Until 1959 numbers 6-10 Owen’s Row remained standing but were then demolished because a new building for Dame Alice Owen’s Girls’ School was to be built on land immediately opposite.

Although in the late-18th century the Owen’s Row houses do seem to have been in single occupation, by the second decade of the 19th century most contained at least two households. This remained so until towards the end of the 20th century. At the time when Richard Cuff was living at number 7 the local papers frequently advertised rooms – or floors – to let in Owen’s Row. In the mid-1850s the weekly rent for one room on the second floor of an Owen’s Row house was 5 shillings. This is now my bedroom.

The majority of the male occupants of the houses were printers, jewellers, clockmakers, or workers in allied trades. The women were lodging house keepers, dressmakers and milliners. The households at no 7 might, in 1851, have been considered slightly more genteel than most. For when that census was taken Richard Cuff, described as ‘artist, engraver (architectural etc)’, was living at number 7 with his younger brother,William, a ‘bookseller -collector’. They constituted one household. The other was headed by John Peacock, ‘Baptist minister at Spencer Place Chapel’, and comprised his wife, son (a printer) and an 18-year-old ‘house servant’. The Chapel was small and situated in a very poor, densely populated area a little to the south of Owen’s Row. That the Cuff brothers should be sharing a house with a non-conformist minister may not have been entirely fortuitous their father, John Harcombe Cuff (c.1790-1852) being a dissenting minister back home in Wellington, Somerset.

Thus, we know that when he painted the watercolour in 1855 Richard Cuff had been living in 7 Owen’s Row for at least four years. However, sometime between 1855 and the next census in 1861 he moved, becoming a lodger in a house in Cumming Street, off the Pentonville Road. By this time his brother William had gone into business as a bookseller with another of their brothers, first in Preston and then in Dover. This could have been a factor in Richard Cuff’s decision to move.

From my knowledge of the proportions of the houses I would suggest that the watercolour is of the front first-floor room of number 7, showing just one of the room’s two windows. Although It is impossible to tell from the 1851 census how the two households were deployed around the house, I suppose we must assume that this room was most likely to have been one of those rented by the artist and his brother. In a search through the local paper, The Clerkenwell News, I found, dated 5 June 1858, an advertisement, headed ‘Unfurnished Apartments’ – ‘To be let, at 7 Owen’s Row, near the Angel, a First Floor and another Room, with use of Kitchen; healthily and cheerfully situated; good references given and required. No other lodgers’. Could this have been inserted at the time when Richard Cuff left the house? Were these his rooms?

Now that we know a little more about the background of the house and its inhabitants let’s look more closely at the decoration of that room in August 1855. Here’s the watercolour again.

Note the plaster moulding frieze, with dentilling, around the ceiling edge, and the marble fire surround. These look entirely typical of the late 18th century but, alas, the originals have long since vanished from the remaining houses so I’m unable to make a direct comparison.

Note the plaster moulding frieze, with dentilling, around the ceiling edge, and the marble fire surround. These look entirely typical of the late 18th century but, alas, the originals have long since vanished from the remaining houses so I’m unable to make a direct comparison.

I suspect that there would originally have been a wooden dado rail running round the room but that, considered dated, had already been removed, allowing the wallpaper to flow from ceiling to skirting board.

The wallpaper looks fairly typical of that fashionable in the 1840s/1850s, at a time when printing machines had brought the use of wallpaper within the reach of all but the poorest.

The window we see is hung with light curtains – perhaps those reserved specially for the summer -and are of printed chintz or muslin. They fall generously, as was fashionable, held back by metal (brass?) tiebacks. As I mentioned, the room has two windows, so the volume of the material in that area would have seemed generous as it pooled to the floor. We can see one shutter in the embrasure; these would, of course, have been pulled across in the evening.

The furniture dates from the earlier part of the 19th century, falling under the general heading of ‘Regency’. The 1858 advertisement that I quote above indicates that the first floor of 7 Owen’s Row was let unfurnished so perhaps we are reasonably safe in concluding that the furniture belongs to the Cuff brothers. In which case to my mind they show rather good taste in matching the style and simplicity of the furniture to the proportions of the room. I’m a little intrigued that one of the pieces, that standing under the window, is a work – or sewing – table. Was it merely decorative? The feet both of it and of the central table end in neat brass castors, facilitating easy movement.

The floor appears to be covered, right close to the skirting board, by a carpet – doubtless of English make – light in colouring. The drugget, rather oddly placed between the worktable and the central table is, of course, lying in front of the artist as he works and is, perhaps, there to protect the carpet from his paints. More usually one might expect to find it under a dining table, catching stray crumbs. A patterned hearth rug with a green border lies in front of the metal fender.

Because it is summer the grate is covered with a chimney board, to provide decoration and give some protection against the intrusion of falling birds and insects at a time when the chimney was not in use.

Among the ornaments on the mantle piece are, at each end, a pair of hand-held fire screens, probably made of papier-mache. Tasselled bell pulls hang at each side. Did the Cuffs ring and young Eliza, the ‘house servant’, answer?

As to the room’s decoration as it relates to the Cuff brothers’ trades – were the books lying on the central table part of William’s stock or collection? And was the picture hanging over the mantle piece one of Richard’s engravings, for it certainly appears to be in black and white. And are the other two, more colourful, pictures examples of his painting?

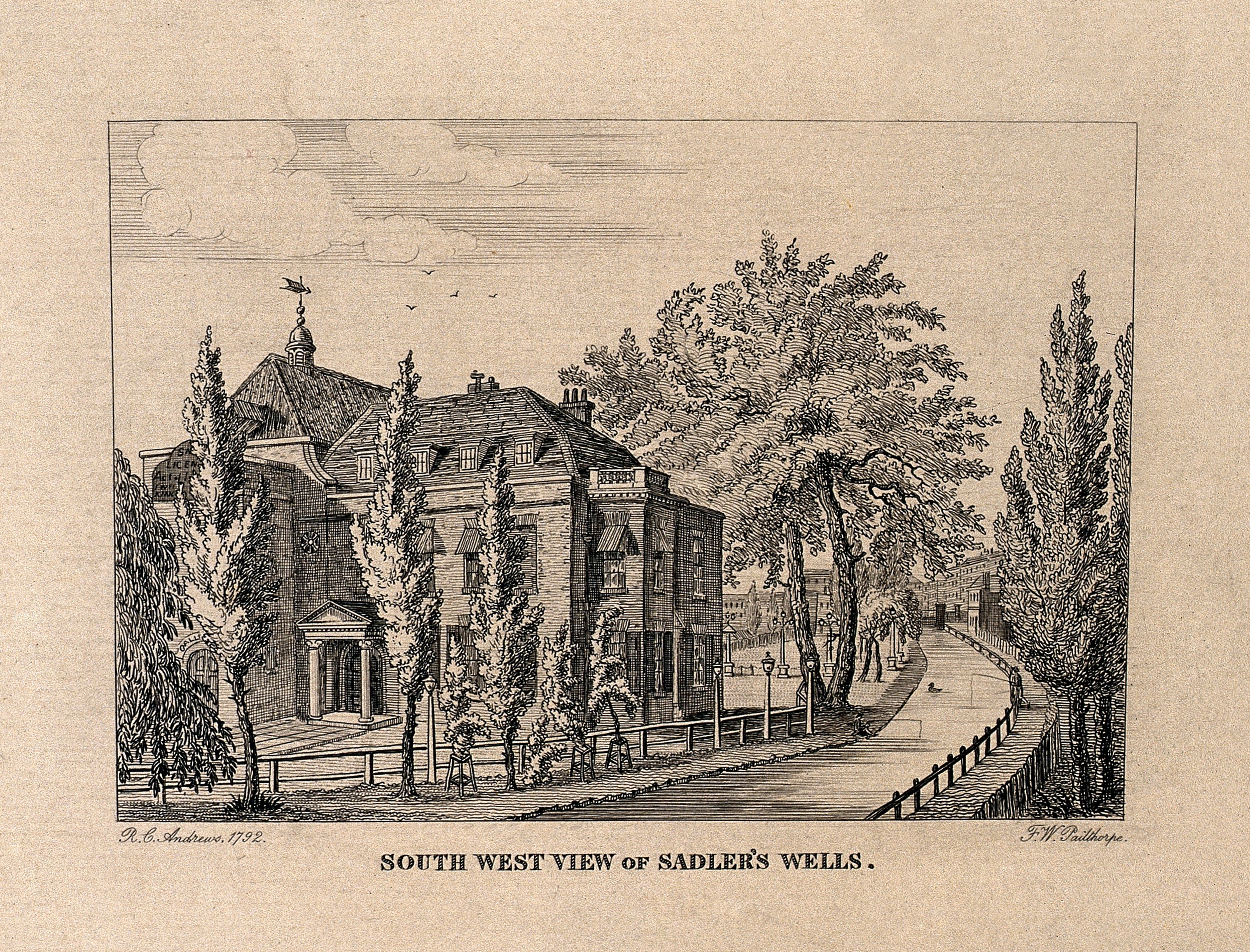

I do wish I could exercise a Street View-type camera and swivel the room around to look out of the window. For the view in 1855 would have been so very different from that of the present day. For then, running along the other side of the narrow Owen’s Row street, was the New River, bringing water from Hertfordshire to its final destination, the New River Company reservoirs just across the road, behind Sadler’s Wells. It was only in 1862 that the New River outside Owen’s Row was covered in. So, looking out of that window, Richard Cuff’s gaze would have travelled over that narrow width of running water and onto the gardens of houses fronting St John’s Street, which led up to the Angel.

And what of the rest of Richard Cuff’s life? I can see that by 1871 he was living at 101 Englefield Road, still in Islington, but to the east of Owen’s Row. He and two of his sisters were the only occupants, apart from a servant, of a comparatively large house. And then by 1880 he had moved again and was now the sole lodger at 5 Thornhill Square, Barnsbury, the house of a ‘commercial agent’and his family. There Richard Cuff occupied two rooms on the first floor and one on the second. All were unfurnished, so perhaps we can picture his elegant Regency furniture, his pictures and his matching papier-mache handheld fire-screens decorating those rooms. It was here that he died on 11 October 1883. He left well over £6000 and, to the British Museum, two letters he had received from John Ruskin, together with many proofs of engravings he’d made for Ruskin. The latter being an exacting master we can assume that Cuff’s engravings were of a high quality.

We’ve caught the merest glimpse into the life of Richard Parminter Cuff and, along with everything else that we will never know, I am left wondering about the woman standing in the sitting room of 7 Owen’s Row in August 1855? On the reverse of the watercolour is a study of the head of a young woman. The information given here – https://tinyurl.com/w3ofoaz – gives the date ‘1885’, but that must be a typo for 1855 – the artist died in 1883. Was the head intended for the figure of the woman? Who was she? and why was she left unfinished? There is a novel to be teased from this picture.