Posts Tagged Mariana Starke

Mariana Starke and the Demon Duke: your opinion requested

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on April 17, 2024

What can anyone truly know of another’s life?

Was it only as the author of the leading guidebook to Europe that redoubtable Mariana Starke (1762-1838) was known to those in high places?

Might her specialised knowledge not have been allied to courage, skill, and ingenuity?

Might she not, in 1828, have unmasked the infamy of a royal duke?

And by doing so determined the complicated fates of crowns and states?

Subscribers to this website will recognise my interest and affection for Mariana Starke, ‘the celebrated traveller’. She was the author of Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent that went through a number of editions in the first three decades of the 19th century. I have researched her early life – and those of her ancestors – in detail and posted a number of articles on this website. I did consider attempting a biography, but reluctantly concluded that there was insufficient primary material covering her later years. I may well be mistaken but, instead, I have had a good deal of amusement in imagining a life for her.

The minutiae of the information she imparted inspired from me an adventure that begins when we encounter Mariana in Rome in January 1828. A malevolent figure, ‘the Demon Duke’, is orchestrating turbulence in Britain and in Hanover. But in Rome events transpire to convince Mariana that she has proof of his infamy. Can she succeed in delivering it? Can she outwit and outrun his proxies?

From Rome we accompany Mariana – and others – on journeys by land and sea, north through Italy and France to a London denouement. We live the roads on which they travel, the cities, towns, villages, and ports through which they pass, the barges, carts, ships, carriages in which they are conveyed, the inns in which they stay, and the food that they eat. Dangers lurk. Of course they do.

The whole is woven around real historical figures and real historical facts. You will know the genre.

My question is, if anyone is sufficiently motivated to venture an opinion,

Should I publish, that is, self-publish, Mariana Starke and the Demon Duke?

Mariana Starke: ‘A Tissue of Coincidences’: Lady Mary De Crespigny And Hortense De Crespigny

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on September 27, 2023

11 The Beacon, Exmouth, onetime home of Mariana Starke

(Photo courtesy of Sylvia Morris and Historic England)

As I mentioned in my last ‘Mariana Starke’ post (The De-Ciphering of Mrs Crespigny’s Diary), I don’t know if, or for how long, the friendship continued between Mariana Starke and Mary Crespigny after Mariana set out for the Continent on 25 October 1791. The last evidence I have found of contact between the two women is the entry Mrs Crespigny records in her 1791 diary, noting she had received letters from Lyons on 3 December – presumably from Mariana and her party. I am sure the correspondence would have continued, at least for a while, but, with no surviving letters or other evidence, I have no proof.

I did wonder if relations between the two women had at some point faltered only because there is no mention, as far as I remember, of Mary Crespigny in any of Mariana’s surviving letters or of Mariana Starke – either in the flesh, as a direct correspondent, or even as an off-stage character – in Mary Crespigny’s one other surviving diary – that for 1809/1810. At this time Mariana was back in England, living in Exmouth, and Lady de Crespigny (as she now was) was meeting regularly, in London and in Bath, friends they once held in common. But, again, the absence of a mention is no proof of any discord.

In fact, the name ‘Starke’ is not entirely absent from Mary de Crespigny’s 1809/10 diary, for on 25 August 1809, while enjoying a protracted stay in Brighton, Lady de Crespigny mentions that she ‘had a present of a turtle from Mr Starke’. There is no suggestion that Mr Starke – this must surely be Richard, her erstwhile lover – was in Brighton at the time – so presumably he had arranged for her to be sent this prime delicacy, Lady de Crespigny doesn’t describe how Mr Starke’s turtle was served, but later in the diary, back in her London house, she does detail a dinner she hosted at which another turtle was the centrepiece of the meal. As turtle was the most expensive and desirable food of the period, a gift such as this would appear to indicate that there had been no lasting rift between Richard Starke and the de Crespignys.

And, from another, rather remarkable source, I think we can infer that, whatever the relations between the two women, Lady Mary de Crespigny was still very much present in Mariana Starke’s thoughts – and speech.

For, in 1840 there appeared in Bentley’s Miscellany, a short story, ‘Are There Those Who Read The Future?’: A Tissue of Strange Coincidences’ in which ‘Mrs Mariana Starke – the celebrated tourist’ features, alongside a mysterious foreigner to whom the author gave the name ‘Hortense de Crespigny’. I could not believe that the conjunction of the names was purely coincidental, so undertook a spot of sleuthing.

The story’s seaside setting of ‘Sunny Bay’ was known to be based on Exmouth, and was, for that reason, reprinted in Memorials of Exmouth (1872) The author of the story was anonymous, merely described as ‘Author of “Recollections of a Prison Chaplain”’. But it did not require much research to reveal him to be the Rev. Erskine Neale [1804-83], the son of Adam Neale (d.1832), onetime physician to the forces. In 1812 one of Erskine Neale’s younger brothers was born in Exmouth and I conclude that the family – at the least the mother and children – spent some time there – at the seaside – before settling in Exeter when Adam Neale returned from the Peninsular War.

Lady Nelson’s House, 6 The Beacon, Exmouth

(Photo courtesy of Exmouth Journal)

In the story another of the real-life characters involved with Hortense de Crespigny is Lady Nelson, the unfortunate widow of Horatio. Erskine Neale appears very au fait with Nelson family affairs, as well he might; his younger brother was married to Frances Nisbet, Lady Nelson’s granddaughter. When Erskine Neale was young, Lady Nelson was living a few doors away from Mariana Starke on The Beacon and I am imagining – yes, imagining – that Mrs Neale was present at ‘Afternoons’ in one or either of the houses and her son was either told – or overheard – scraps of conversation by or about the older women. He must also have encountered Mariana Starke in person, for his depiction of her attire and style of speech accords with the memories of other of her contemporaries.

My thinking is that, as a boy, Neale noted that ‘Lady de Crespigny’ featured frequently in Mariana’s conversation and, many years later, when searching for a suitably foreign name for his mysterious character, ‘de Crespigny’ sprang to mind. Erskine Neale accorded Hortense de Crespigny with the ability to foretell the future and, at the end of the tale, suggests she may have acted for the British government in some ‘cloak and dagger’ capacity. I doubt that it was in those terms that Mariana Starke discussed Lady de Crespigny but, let me just say that the tale is a ‘Tissue of Strange Coincidences’ on more than one level. A mysterious remark on which I may elaborate before too long.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.

Mariana Starke: The De-Ciphering Of Mrs Crespigny’s Diary – And What It Reveals

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on September 4, 2023

In 2011 I made an enjoyable flying visit to Oxford to spend a few hours in the Bodleian Library reading quickly through a diary that the Library had lately acquired, a 1791 ‘Ladies Pocket Journal’, catalogued as having been written by a ‘Mrs Starke’.

As a result, I was able to identify the writer of the diary not as ‘Mrs Starke’ but as Mrs Mary Crespigny (1750-1812), patron and friend of Mariana Starke (see The Mystery of the Bodleian Diary). But I was unable to explain why, throughout the year, the male figure dominating the entries, whom in my innocence I assumed to be her husband, was referred to as ‘Starke’.

When I mention that many of the entries were written in a form of cipher, that in my original post I remarked that ‘It only now requires a cryptographer to set to work to decode the sections that she wished to keep safe from prying eyes’, and that, twelve years later, my wish has been granted, you may well see where this is going.

For I am now in possession of both a key to the cipher and a rough translation of the coded entries, which reveals beyond a peradventure that Mary Crespigny had formed ‘an attachment’ to Richard Starke, Mariana’s younger brother. Writing his name – ‘Starke’ – in plain text, Mrs Crespigny notes his presence almost every day – and evening – at Champion Lodge, the Camberwell home she shared with her husband, Claude Crespigny. Even if absent, Starke’s whereabouts are noted. In the coded passages his name is never spelled out, but it is clear that it is ‘Starke’ who is at the centre of Mrs Crespigny’s world. ‘Mr C.’ is occasionally mentioned, invariably favourably, but it is not on him whom her thoughts are concentrated.

Richard Isaac Starke was baptized at Epsom on 4 January 1768 and so in 1791 was 23 years old, eighteen years younger than Mary Crespigny, and three years younger than her only son, William. A member of the 2nd Regiment of Life Guards, Starke was promoted lieutenant in May 1791, his responsibilities not, apparently, particularly arduous. At intervals he undertook unspecified guard duties, which, on one occasion in February 1791, involved accompanying the King to the Opera.

The first mention I can uncover linking Richard Starke and Mary Crespigny is a notice in the 7 April 1789 issue of The Times, reporting that ‘At Mrs Crespigny’s temporary theatre at her house at Camberwell Miss Starke and Mr Starke took part in The Tragedy of Douglas’. The other actors, all amateurs, included William Crespigny as ‘Douglas’, the lost son of the heroine ‘Lady Randolph’, who was played by Mrs Crespigny to Richard Starke’s ‘Lord Randolph’. It is likely, however, that Richard Starke and Mary Crespigny were already well acquainted. Although I assume that it was through his sister that Richard Starke entered Mrs Crespigny’s orbit, I do not know when exactly the two women first met. Mrs Crespigny was certainly the inspiration for Mariana’s long poem, The Poor Soldier, published in March 1789, a month before the theatricals, and that work must have been a good while in the gestation. In fact, in her dedication, Mariana describes Mrs Crespigny as having ‘long honoured’ her with ‘flattering, though undeserved partiality’. Anyway, even if they had not done so previously, while playing husband and (unhappy) wife in Douglas, Richard Starke and Mary Crespigny had every opportunity to bond.

The following year, in April 1790, Richard and Mariana Starke again took part in Mrs Crespigny’s private theatricals. This time Mariana was the author, the play The British Orphan, never published, is now known only through a lengthy description in The Town and Country Magazine (vol 22, 1790). Mrs Crespigny was again the heroine and was particularly noted by the European Magazine and Theatrical Journal (April 1790) as appearing in three different dresses. Richard Starke played one of two friars, the other being R.J. S. Stevens, a composer who for the production set to music a poem written by Mariana. In his Recollections of a Musical Life (p.70) Stevens observed that Mrs Crespigny had wanted Caroline, a daughter of Lord Thurlow, to sing in this piece but, when consulted by Lord Thurlow, he (Stevens) disapproved ‘and I was inflexible. Private Theatricals I have ever considered as a species of entertainment very injurious to young minds; destructive of their innocence and modesty; and equally endangering their peace and happiness.’ When quoting this in my previous post about The British Orphan I did not know what I now know. Perhaps the Camberwell frolics had helped shape Stevens’ attitude.

Despite his Life Guard duties, Richard Starke not only had the time and inclination to take part in theatricals but had also put his pen to work, writing the epilogue to Mariana’s next play, The Widow of Malabar, which was given its first public performance, at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, a month after the staging of The British Orphan. The printed edition of The Widow of Malabar carries a dedication by Mariana to Mrs Crespigny, dated 24 January 1791. The first full entry in Mrs Crespigny’s 1791 diary would appear to indicate that she attended a production of The Widow of Malabar on 12 January – and may have gone again on the 19th. Even if she did not attend in person, she made sure that ‘Miss Starke had a very full house. I sent vast numbers – filled 10 rows of pit & nearly all the Boxes…’ On 16 February she wrote in her diary: ‘My wedding day – been married 27 years – We dined without company – Starke and I went to the Widow of Malabar in the eve.’ How conventional I was to think that on her wedding anniversary it was with her husband that she attended the play.

However, the cipher entries make clear that the ‘attachment’ (as she often refers to it) was tempestuous. She records frequent quarrels and tiffs. For instance, in March,

‘[Starke] and I were very happy till sometime after supper when he grew peevish and we tiff’d. He certainly rather cut and he is then generally out of humour. He said I was the wretchedest creature upon Earth – that he lived a wrong life….We made it up and the next morn were as good friends as ever.’

That is the pattern; it must have been very wearing. Doubtless it was the ‘making up’ that fuelled the affair. I suspect that a not-infrequent marginal mark records the instances of ‘making up’.

However, throughout the year Starke’s ‘propensity for drinking’ and womanising – with at least one prostitute (‘he told me that he had been naughty and taken a dolly out of the street to his own room…he told me he wd not go to any of the houses…what signifies it to me for this proves that his forbearance is at all end as we had not had the least quarrel nor was the least in liquor’) – caused Mary Crespigny great distress. While, as I’ve mentioned, she had no qualms about recording Starke’s constant presence in her plain text diary entries, Mary Crespigny confines her anguish to cipher. After one incident she wrote in code that ‘I complained to his sister tho very sorry to do so – she behaved vastly well and determin’d if he gave me further uneasiness that his mother [should] speak to him.’ The next words translate as ‘Mrs Stake’ – but can only mean ‘Mrs Starke’. So, here is the clearest evidence that not only was the ‘attachment’ known to Mariana, but that she knew that her brother used her patron ill.

The ’attachment’ was still in place at the end of December 1791 and we do not (for the moment, at least) know how it ended. But end it did. Richard Starke married in 1798 – not that that would necessarily prove anything – and Mary Crespigny’s only other surviving journal – covering April 1809-December 1810 – makes no mention of any Starke, either brother or sister. It does, however, frequently allude to her husband, now Sir Claude de Crespigny, and her son, William, who, with his family, received only a couple of mentions in 1791. And, interestingly, it contains no cipher entries. Presumably Mary Crespigny now had nothing to hide.

A ‘complaisant husband’?

That this lens through which to peer into late-18th-century life as actually lived should have been offered by Mary Crespigny is particularly pleasing, as it is as the author of a guide to a young man’s conduct that her literary fame rests.

Letters of Advice from a Mother to her Son was published in 1803, although Mary Crespigny’s dedication, to the Archbishop of Canterbury, claims the letters were originally written for ‘partial instruction to a beloved Son’ and, before publication, ‘remained by me many years unthought of…’ If that were so we could conclude, from the content, that they had been written when William was around 16 or 17 years old – perhaps circa 1782. The surprisingly frank essays treat matters religious, sexual, and socially practical. Of these one, Letter XXVII, headed ‘Attachment’, appears particularly relevant to Mrs Crespigny’s situation as revealed in her 1791 diary.

She states:

‘the uneasiness we are entangled in, for which accuse fortune or abuse others, is generally the offspring of our crimes or imprudence; by giving way impetuously to improper passion, we ourselves inflict the wound that is afterwards our torment: -no crime or folly is more likely in the end to produce this torment, than a forbidden attachment, which too often pursues its fatal course, at first, possibly, under the appearance of friendship; – and, by degrees almost imperceptible, it is then suffered to become that forbidden attachment, which, if its insinuating poison is not well guarded against, will certainly destroy the feelings of honour, truth, and virtue, and render the self-devoted victim a wretched slave to duplicity, falsehood, and criminality….Too often the person committing it is one in whom the greatest confidence is placed – the apparent friend of the family, daily partaking of its hospitality, and, with a seared conscience, receiving its favours….To be received into a house, to be treated there by the master of it with hospitality, kindness, and friendship, possibly to receive favours from him…to return all this with duplicity….is such a breach not only of hospitality, but every tie moral and divine…’

Whether this ‘Letter’ was written in the 1780s, well before the Starke adventure (although who is to say she had not had previous such ‘attachments’?), or whether written nearer the date of publication, in which case we know she was able to speak of ‘torment’ from experience, one might feel that Mary de Crespigny was taking something of a risk in moralising so sternly on the subject. For, eighteen years or so earlier, her ‘set’ could have had few doubts as to the nature of her relationship with the young man who lived in her house and accompanied her around town. In fact, the reviewers gave far more consideration to her views on religion or duelling or idleness than on ‘Female Connexion’, of which ‘Attachment’ was an element. However, The Critical Review (vol 1, 1804) did praise her for taking ‘off the mask which disguises some of her sex; we wish she had done it more generally; but she probably knows nothing of the worst part.’

Contrast that pious sentiment with this October 1791 entry, in cipher, in Mary Crespigny’s diary:

‘ He took me into another room and told me that he had been very foolish that a woman at a window had nodded to him and he went to her – how changed must be he feel towards me and how little attention he pays to my happiness any way – when assaild by strong temptation or when absent and when he has drunk too much he may have some excuse but after what has pass’d between us and while he chuses to continue to live with me he ought to pay some attention to my feel[ings] – shew some forbearance. It wd at any rate be mean[?] in to continue attach’d to him as I have been for he is clearly tired of me and he now gives way to what dear Mr C says is Libertism. I will suppress my feel[ings] – so far as not to make him an outcast from the house that wd be ruin to him but I am resolved to conquer my ill placed attachment to him and be only upon common terms with him.’

Knowing that Mary Crespigny was indeed well aware of ‘the worst part’, I wonder if this makes her observations as to the conduct to be expected of a young gentleman more or less persuasive?

In fact, a reading of the plain and cipher text of Mrs Crespigny’s 1791 ‘Pocket Journal’ provokes any number of questions around attitudes to morality held by her contemporaries. As such it will surely prove an interesting new resource for historians of late18th-century ‘upper-middling’ society.

Bodleian Reference for Mrs Crespigny’s 1791 diary.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.

With thanks to the anonymous cryptographer who cracked Mrs Crespigny’s cipher and to Nigel à Brassard for generously sharing the resulting key and text.

Mariana Starke: ‘Buy A Copy’: recently discovered letters of the 19th century travel guide writer Mariana Starke

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on January 5, 2016

Last year – 2015 – was such a ‘suffragette year’ that my various other interests were sadly overlooked. Now, at the very beginning of 2016, I would like to make amends and bring once more to the fore Mariana Starke, my favourite lady of the late-18th/early-19th centuries.

Last year – 2015 – was such a ‘suffragette year’ that my various other interests were sadly overlooked. Now, at the very beginning of 2016, I would like to make amends and bring once more to the fore Mariana Starke, my favourite lady of the late-18th/early-19th centuries.

For at the very end of 2014 I had the great good fortune to meet Gerlof Janzen, who had just published a most interesting collection of letters written in the mid-1820s by Mariana to a Surrey gentleman, Edgell Wyatt Edgell. We know of Mariana as the ‘celebrated traveller’, the author of Letters from Italy, which over the years transformed itself into Travels on the Continent –the guidebook to Italy – and to Europe – but the newly-discovered letters to Edgell Wyatt Edgell reveal her in another light entirely – as a businesswoman.

Travels on the Continent was revered – and sometimes mocked – for the painstaking detail with which Mariana itemised the cost of travels – from washing petticoats in Venice to sending out for a meal in Rome. In the Edgell letters we see how such preoccupation with practical details was second-nature to her, although, in this instance, her concern was the business of acquiring copies of celebrated paintings, suitably modified in size and shape, to adorn the home of a Surrey gentleman. Thus we find her busy with measurements, with artists and framers, and with the cost and method of arranging for the safe carriage of the goods from Rome to England.

Among the paintings that she shipped to Edgell were copies of ‘Schidone’s Charity, Titian’s sacred & profame Love, & the Battle of Constantine; all of which will be properly stretched, varnished, packed, & sent by sea to Leghorn…'[p57]. She detailed how, to save money, she would be ‘packing the pictures myself, by the aid of the carpenter employed to make the packing-case & then consigning them to the care of Lowe – the Wine Merchant – to be, by him, conveyed to the Ripa Grande; thence to Leghorn; & thence to Messrs Calrow, London…’. She then accounted, in a most complicated fashion, for all the costs.

In addition to her labours on Edgell’s behalf a letter to him of 13 April 1825 recounts how, at the last minute, she had included in the shipment one other painting destined not for Edgell but for ‘Mrs Shelley’. This was ‘a small portrait of Mr Shelley, Lord Byron’s great Friend, who was drowned near Pisa…’ She explained that ‘the extreme anxiety expressed by Mrs Shelley to have this picture sent to England, has induced me to give you this trouble, instead of waiting to take it myself.’ This portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley was that painted in Rome in 1819 by Mariana’s friend, Amelia Curran. Mary Shelley was desperate to have this only likeness of her beloved husband – even though the artist herself was less than satisfied with it. This painting, the only one done in his lifetime, now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London and, when you stand and view, give a thought to Mariana Starke labouring with the carpenter to fit it into the packing case. What a subject for a student of ‘material culture’.

Edgell Wyatt Edgell was clearly a friend of Mariana’s; she had known his wife in Surrey in the early 1790s, before their marriage. So – was the service she provided in finding copies to decorate Edgell’s mansion peculiar to this friendship, or did she do so for others? I suspect that she did act as an informal agent general, capitalizing on her knowledge of the Roman art scene and on her reputation as a practical woman of the world. Just as the Edgell Wyatt Edgell letters eventually hove into public view, nearly 200 years after they were written, perhaps there is another cache of ‘Mariana’ letters yet waiting discovery which will throw further light on her activities.

Gerlof Janzen’s edition of these Mariana letters – published as Buy a Copy – is wonderfully readable, bringing Mariana to life and, in his essays and notes, illuminating her world – Rome, Sorrento and Exmouth.

The book – with numerous illustrations – can be obtained from its publisher,

Robert Schreuder

Nieuwe Spiegelstraat 48

1017 DG Amserdam

The Netherlands

email: info@robertschreuder.nl

Copyright

Mariana Starke: First Productions

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on January 7, 2013

In 1787 J. Walter, a London publisher/bookseller operating from premises close to Charing Cross, issued – as Theatre of Education – a new English translation of Le Théâtre á l’usage des jeunes personnes, a collection of comedies by Mme de Genlis, the first woman to be appointed tutor to princes of France.

This innovative method of providing a moral education for children through the use of short plays had proved immensely popular on both sides of the Channel. First published in France in July 1779, an English translation, under the imprint of T. Cadell and P. Elmsly ; T. Durham, appeared in 4 octavo volumes in 1781, with a new edition, in 3 volumes, under the same imprint, following in 1783. [See http://archive.org/details/theatreeducatio07genlgoog for the online edition of the 1781 4-volume edition]. Nowhere is the name of the translator of this edition stated, although it is thought that he was male. As far as I know he has never been identified – although this really is not my field and I would welcome correction.

Nor, indeed, is there any indication on the title page of the J. Walter edition of the names of the translator(s) of his edition. It was not until 1831, when an obituary of Mrs Millecent Thomas (the former Millecent Parkhurst -see Mariana Starke: An Epsom Education) appeared, that the truth was revealed.

As the Annual Register and The Gentleman’s Magazine reported, Mrs Thomas ‘assisted her friend Miss Starke in translating Mme de Genlis’ Theatre of Education’. Over 150 years later, in Notes and Queries (45:1; March 1998), Edward W. Pitcher identified the edition translated by Mariana and Millecent as that published by J. Walter. The Annual Register had cited the translation as being issued between 1783 and 1788 in three duodecimo volumes, although a consultation of COPAC reveals no J. Walter edition pre-dating 1787. It does, however, seem to have been issued in a variety of formats. The 3-volume British Library set appears to be inscribed, if I have deciphered the handwriting correctly, ‘Miss M.B. Woollery, the gift of her friend Mrs Thomas’. Millicent Parkhurst married the Rev Joseph Thomas in 1791, the gift, if it really was from her, presumably post-dating her marriage. The only advertisement for the J. Walter edition that I have found appears in The Times, 28 July 1790, and refers to a set of four-volumes, at the not inconsiderable price of 10 shillings. J. Walter was the publisher of, among a wide variety of productions, Mrs Chapone’s works – including Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, a seminal conduct book for young women of the period. He had presumably thought it worth backing a translation of Theatre of Education to rival that issued by Cadell et al, although doubtless he had paid little to the youthful translators. It does not appear to have merited either a reissue or a second edition.

So we find that the two young women, still in their mid-20s, living in Epsom, across the road from each other, had embarked on a new translation of a much-fêted work which they had then succeeded in getting published. Not that this, when we know their circumstances, is particularly surprising. For, by the 1780s, Millecent Parkhurst and Mariana Starke were well-educated young women, with influential literary contacts. We have noted that John Parkhurst, Millecent’s father, and William Hayley, to whom Mariana was a ‘poetic daughter’, both gave encouragement.

Mariana Starke was also on intimate authorly terms with George Monck Berkeley (1763-93), a precocious literary talent. In a letter written to him at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, on 22 August 1787, Mariana reveals ‘that I am now much better qualified to write a Tragedy than when I composed the first three Acts of Ethelinda, as I have lately studied dramatic composition with great diligence.’ She is referring to a play, Ethelinda, which she and Monck were writing together. It is tempting to conclude that her reference to recent dramatic composition might not be unrelated to the work involved in producing the translation of Mme de Genlis’ plays. A few sentences later she tells Monck that ‘After I had finished Ethelinda to the best of my abilities, I carried it to my excellent Friend, Mr Parkhurst, whose almost paternal regard for me prompted him to consider it with great attention: he has corrected all the errors which happened to strike him; and advises me to let every material thing stand as it is now, saying, he thinks the Play very dramatic, and very likely to be well received: As he has condescended to take infinite pains with the Piece, I am sure you must agree with me in thinking it would be extremely indelicate to put any Critic over him, especially as Mr Parkhurst (from the soundness of his judgment and the depth and universality of his knowledge), is perhaps of all men in this Kingdom, best qualified for the office of a Critic. I have, in conformity to your advice, shortened my own acts and lengthened yours; and I have studied to insert the many excellent speeches, with which your acts abound; but sorry am I to say, that there is one sweet speech on fame, which I know not how to introduce according to the present plan of the Play. Your speech on murder, which is, by the by, the finest thing I ever read, I have put into the beginning of the Play, where it shows to great advantage; and many more of your lines I have occasionally introduced among my own, by way of giving a strength to my composition, which it seemed to want. I find, from Joinville, that the Crusaders always crowned their Heroes with palm, therefore I have substituted that for laurel. I am told by a Gentleman who is deeply read in the records, that even Kings, in the time of Richard the 1st, did not espouse what we now call the regal style; therefore I should think Ethel had better not do it – and I have taken the liberty to alter the two last lines of Bertram’s [?] dying speech, because (if Homer may be credited) no man, who dies of a wound in the breast, can see objects immediately before his death. I have applied to a Friend for Mrs Siddons’s interest but am not certain how I shall succeed – if I was more intimate with Mrs Soane [?] I would certainly write to her; but slight as our acquaintance is, it would be too presumptuous – from you, perhaps, she might receive an application graciously. Another Friend of mine, who is acquainted with Linley and King, has undertaken to introduce Ethelinda and me to both of them, and I almost daily expect a summons to appear before those mighty Rulers of the Theatre. So, if you have any interest, work it now, let me entreat you. Linley, at present, is at Bath, but he will speedily return to London.’

Thus, it is clear that by 1787 Mariana Starke was working her apprenticeship as a playwright and knew how to network the theatrical scene. (Mrs Siddons was the most famous tragic actress of her day; Thomas Linley and Thomas King were both involved with the management of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.) It is virtually certain (although I have not yet found any pre-1788 evidence) that Mariana was already well acquainted with Mrs Mary Crespigny (see Mariana Starke: The Mystery of the Bodleian Diary), who organized dramatic performances at a private theatre erected in the grounds of her Camberwell home. The success of The Theatre of Education was predicated on the willingness of families, such as the Crespignys, to stage short plays for amusement – and instruction. For an interesting article on the relationship at this time between private theatricals and public theatre see here.

Although the translators of the J. Walter edition are not named, the ‘Advertisement’ that prefaces the text at least makes clear that they were women. ‘The fame acquired by Madame de Genlis is so deservedly great, and the Theatre d’Education so universally considered as her chef-d’oeuvre, that it naturally becomes the study and admiration of her sex; some of whom, in order to amuse their minds, and at the same time amend their hearts, by imprinting on the memory such exalted precepts as those contained in the Theatre d’Education, undertook to translate it into English, and have now, to the best of their abilities, finished this Work, which they presume to place before the eyes of an indulgent Publick….[so that].people of all ages and all ranks may derive from the Original of Madame de Genlis, the most useful and persuasive lessons, couched in the most eloquent and characteristic language.

I have only compared the two editions in the most superficial way, but, even so, could immediately detect distinct differences in the language used. It was presumably because they felt something wanting in the 1781 translation of Mme de Genlis’ work that the two young women felt encouraged to embark on their own. However, The Critical Review, while conceding that there were faults in the 1781 edition, could not bring itself to praise the J. Walter edition.

The translators make clear in the Preface to the J. Walter edition that they had sought Mme de Genlis’ permission to publish their translation of her work: ‘Permit us, Madam, thus publickly to return our most thankful acknowledgements for the honour you confer upon us, by allowing the following translation to be inscribed to your name; an honour which demands our gratitude in an especial manner, as we do not enjoy the happiness of your personal acquaintance’. There had, presumably, been an exchange of letters between Epsom and France. Unfortunately there is no correspondence (or, at least, none that I have found) that throws any more light on either the production of the translation of the Theatre of Education or its afterlife as it related to the life of Mariana Starke. I have come across no reference at all to the work in any subsequent correspondence. This is perhaps just a little surprising.

We do know, however, the fate of the other work mentioned with which Mariana was involved – for, on 30 October 1788 [at least, I think it was 1788, but it may have been 1787 – the dating of the letters is uncertain], her mother, Mary Starke, wrote from Epsom to George Monck Berkeley a letter in which she she mentions that Mariana is awaiting ‘something decisive respecting the fate of the rash, yet beauteous Ethelinda.. You long ago were informed that this heroic Damsel was presented to, and rejected, by the respective Managers of Drury Lane and Covent Garden. Her next application was to Mr Colman [of the Theatre Royal, Haymarket] who paused a long while upon the question, her merit making a deeper impression upon his mind, than upon either of the other Gentlemen. Yesterday, and not before, his determination reached Epsom – ‘That he thinks the piece distinguished by many touches of Poetry, tho’ on the whole too romantick ..for the Theatre. ‘…The dear Authoress has laid aside her pen, and taken up her distaff, in other words, her time now is chiefly occupied in inquiring as to the practicability and possibility [?] of establishing Sunday Schools & Schools of Industry in this neighbourhood. How much more becoming in a Female [?] is this than dabbling in ink. However I have derived so large a portion of amusement, not to say instruction, from some female Writers of the present age that I cannot subscribe implicitly to this opinion, worthless perhaps it does not seem proper and may so claim an exception from this lordly privilege on behalf of my own daughter. Therefore she, as I told you before, is resuming the primitive employment of the distaff. Let her rejoice at the success attendant upon the fair Heloise….’

The latter remark may refer to Monck Berkeley’s Heloise: or the Siege of Rhodes, published in 1788. Ethelinda, clearly a play set at the time of the Crusades, does not alas, appear ever to have been staged. However we know that Mariana Starke certainly did not take up the distaff and devote herself to ‘Sunday Schools & Schools of Industry’ but, if the dating of her mother’s letter is correct, had already, on 8 August 1788, seen another of her plays – The Sword of Peace – given its first public performance at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. George Colman had, as we shall discover in the next Mariana Starke post, proved most supportive.

The latter remark may refer to Monck Berkeley’s Heloise: or the Siege of Rhodes, published in 1788. Ethelinda, clearly a play set at the time of the Crusades, does not alas, appear ever to have been staged. However we know that Mariana Starke certainly did not take up the distaff and devote herself to ‘Sunday Schools & Schools of Industry’ but, if the dating of her mother’s letter is correct, had already, on 8 August 1788, seen another of her plays – The Sword of Peace – given its first public performance at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. George Colman had, as we shall discover in the next Mariana Starke post, proved most supportive.

Sources: Berkeley mss, British Library

Copyright

Mariana Starke: An Epsom Education

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke, Uncategorized on October 8, 2012

Mariana Starke was christened at Epsom Parish Church on 23 October 1762. On 19 June, barely four months earlier, and three years into their marriage, her parents had buried their first-born child – a son, John – in the church’s graveyard. Mariana was to be an only child for six years – until the birth of her brother, Richard Isaac Starke, in 1768 – and to be an only daughter until the birth of her sister, Louisa, in 1772. Although there is no record of other children having been born in the years between the births of these living children, the gaps are significantly long, suggesting the possibility that Mary Starke may have suffered miscarriages. Certainly Richard’s father, John Starke, while leaving his eldest son only Hylands House in his rather punitive 1763 will, seems to have expected him to sire at least five children – to all of whom the grandfather was prepared to leave handsome legacies.

We know no firm details of Mariana’s early life as she grew up in Epsom. She may have had a governess, but more likely was taught by her mother, who from her letters appears a competent, amusing woman, interested in literature and the world. The only extant reference I have found to the hiring of a teacher occurs in one of Mrs Starke’s letters, in which she mentions that she is thinking of engaging a music master for her daughters.

This letter written, probably, in 1781, is to Mrs Hayley, wife of William Hayley, an influential man of letters and, in his life-time at least, a highly-regarded poet, patron of William Blake, friend of Cowper, of Romney and of Mariana Starke, who was to him his ‘dear poetical daughter’. The earliest letter in the extant correspondence between the Starkes and the Hayleys dates from 1779 and it is clear from the tone and language employed by the writers that the two families were on close and affectionate terms – and would appear to have been so for some time. There is no indication, however, of how or when the introduction between the families took place. Mariana’s earliest letter in the sequence, dated 22 December 1780, is to Mrs Hayley inviting the Hayleys to ‘a little Hop’to be held by her family early in the new year – on Monday 8 January – and to dinner the day before. At this time the Hayleys lived at Eartham in Sussex, about 45 miles south of Epsom. Hylands House was on their route into Town; in another letter Mrs Starke mentions that she could look out for their chaise as it passes along the Dorking Road. When she wrote this letter of invitation Mariana was 18 years old and entirely at ease in corresponding with the older woman.

From her mother’s letters we can catch glimpses of this youthful Mariana. In November 1780 (?) when Mrs Starke suffered a a bout of illness, during which exertion ‘produced a spitting of blood’, she was ‘an affectionate un-wearied attendant under Providence’ ‘her tenderness contributes materially to my recovery….I can read a little, and so my daughter ransacks the circulating library for my amusement and has brought me the life of Garrick, written by Davies, the materials supplied by Johnson and the whole regulated by him. Tis very entertaining; it contains a history of the Theatre for 36 years. I remember many of the persons mentioned. It likewise comprehends an account of the contemporary dramatic Writers. What an assemblage of opposite qualities met in ‘Dr Goldsmith’ without one particle of common sense to rectify the composition.’ Davies’ life of Garrick was first published in 1780, suggesting that the Epsom circulating library was quick to offer the latest published works and that Mariana had been prompt in her ‘ransacking’. From the list of books catalogued when the stock of the Epsom circulating library [as far as I can establish this was the only circulating library in Epsom during this period] was put up for auction in 1823 it is clear that there was no shortage of reading matter likely to appeal to both mother and daughter. For instance, quantities of novels and book of travels dating from the 1780s were still held in the stock of the library at the time of its sale – novels such as Aspasia, the wanderer (1786), Alfred and Cassandra (1788), Letters of an Italian Nun (1789) and Adeline the Orphan (1790).

By the 1780s Epsom’s heyday as a spa town had passed but, in a healthy position close to the Downs and close to London, it attracted well-to-do merchants quite prepared then – as now – to commute into town on business. Although he had no necessity to make this journey regularly, ‘Governor Starke’ – by which slightly inflated version of his former title Richard Starke is often named in contemporary accounts – still some had business with the East India Company. By virtue of his stock holding in the Company he was able to vote for candidates to the Directorate of the Company and probably made periodic visits to their headquarters in Mincing Lane – a stone’s throw from the house in which his grandfather, Thomas Starke, the slave trader, had lived 100 years before. It is interesting – if useless – to speculate as to whether a knowledge of the lives of his forebears was incorporated into his perception of the world. Did he know – as we shall never – that his father had turned to India because he did not wish to be involved in the trade in Africans of which Thomas was a pioneer? Or, what is more likely, did he know that John Starke had seen that the Virginia tobacco trade was taking a downward turn – and was tediously prone to litigation – and that India was the new Virginia? Whatever his thoughts as he walked along Mincing Lane Richard Starke would have been well aware of the importance in Starke family history of the church of St Dunstans in the East, just three minutes walk away, down towards the river. Besides his grandfather – and all the late-17th- c infant Starkes buried there, it was here that his own mother had been interred in 1730 and here, five years later, that his wife, the daughter of a merchant, had been christened. That, at least, should have inculcated a proprietorial feeling for this small area of the City in a man who had spent his working life in India and now lived a rather secluded life in Surrey. Again, idle to speculate, but surely, on occasion, Mariana would have been taken to the City. Would she not have been curious to see the streets where her forebears lived?

For Mariana, we know, was in her youth passionate about ‘antiquity’. In 1781 her mother, writing to Mrs Hayley, mentions that they had visited ‘Cowdry’ [Cowdray, a Tudor house in Sussex that in 1793 was reduced to ruins by a fire but whose magnificence was still intact when the Starkes visited], remarking that ‘The outside is striking, fine, venerable and claims respect, but within tis unequal and disappoints the expectation. Perhaps altogether no ill emblem its owner. Marian was pleased; I am not so rapturously fond of antiquity as she is. At her age I was, but my passion for gothic structures, and tragedy, expired at the same moment. When the gaiety of youth is fled, lively scenes become necessary.’ So, here is a glimpse of a Mariana swept up in the zeitgeist for the gothic – her ‘sensibility’ a counterpoint to her mother’s ‘sense’.

‘Sense’ was, I am sure, a virtue with which Mariana’s closest contemporary companion of her youth was liberally endowed. Millecent Parkhurst, who was a few months younger than Mariana, lived with her parents in Abele Grove on the other side of Dorking Road from Hylands – on the way into Epsom town. Then an elegant house, with coach house, stables and grounds of about 1 acre, Abele Grove is now, rather bizarrely, the Epsom Central branch of the Premier Inn chain, But it is there still – as is Hylands House – and you can still walk along the Dorking Road between the two- either on your own two feet or, thanks to Google Street View, on your computer.

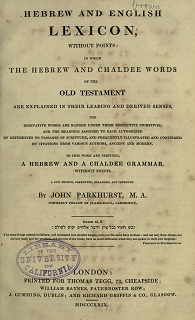

Millecent’s elderly father, John Parkhurst, had inherited valuable estates around Epsom and, although a clergyman, of the high Anglican variety, felt neither the necessity nor inclination to seek preferment. His life was devoted to scholarship; amongst other writings he had published both Hebrew/English and Greek/English Lexicons (the latter to the New Testament). When, in 1798, after his death, a new edition of this work was called for, it was published with Millecent as editor. In the preface to the 5th edition, a later editor recorded that she was ,’reared under the immediate inspection of her learned and pious father, by an education of the very first order, [and] has acquired a degree of classical knowledge which is rarely met with in the female world’. In a 1787 letter (to be considered at greater length in a subsequent post) Mariana mentions ‘the almost paternal regard that [Mr Parkhurst] has for me.’ It would, I think, be safe to assume that Mariana spent a considerable time in that household, that she was at home in John Parkhurst’s library and, with Millecent, benefited from his teaching. See here to view portraits of John Parkhurst and his wife – held at Clare College, Cambridge. If the date (1804) attributed to the paintings is correct they were commissioned some time after the pair had died – John in 1797 and Millecent in 1800.

Millecent’s elderly father, John Parkhurst, had inherited valuable estates around Epsom and, although a clergyman, of the high Anglican variety, felt neither the necessity nor inclination to seek preferment. His life was devoted to scholarship; amongst other writings he had published both Hebrew/English and Greek/English Lexicons (the latter to the New Testament). When, in 1798, after his death, a new edition of this work was called for, it was published with Millecent as editor. In the preface to the 5th edition, a later editor recorded that she was ,’reared under the immediate inspection of her learned and pious father, by an education of the very first order, [and] has acquired a degree of classical knowledge which is rarely met with in the female world’. In a 1787 letter (to be considered at greater length in a subsequent post) Mariana mentions ‘the almost paternal regard that [Mr Parkhurst] has for me.’ It would, I think, be safe to assume that Mariana spent a considerable time in that household, that she was at home in John Parkhurst’s library and, with Millecent, benefited from his teaching. See here to view portraits of John Parkhurst and his wife – held at Clare College, Cambridge. If the date (1804) attributed to the paintings is correct they were commissioned some time after the pair had died – John in 1797 and Millecent in 1800.

The Rev Parkhurst was not only Mariana’s advisor and critic but, with William Hayley, was responsible for inducting Mariana into the literary world. In 1781 she was among the subscribers to Ann Francis’ Poetical Translation of the Song of Solomon, from the original Hebrew, published by J. Dodsley. John Parkhurst subscribed six copies and it is to him that the book was dedicated, with a credit for supplying Notes. Among the female Epsom subscribers were Mrs Foreman, Mrs E. Foreman, Miss Foreman and Mrs Phipps. The latter ladies, who were presumably of a literary incline, were unlikely to have been those of whom Mariana wrote to William Hayley on 1 October 1781, ‘I spent an afternoon a short time since in company with Mrs Francis. She appears perfectly good-natured and unaffected – our Epsom Ladies were quite astonished that she should be in the least degree like other people – one observed that she really dressed her hair according to the present fashion, another, that she had a very tolerable cap, and a third that she certainly conversed in a common way, in short they spoke of her, as tho’ they had expected to have seen a wild beast instead of a rational creature, & I felt myself very happy that they were perfectly ignorant of my ever having made a Poem in my life.’ In her preface Ann Francis had felt it necessary to defend her translation of this particular text on two counts – in case it might ‘be thought an improper undertaking for a woman [since] the learned may imagine it a subject above the reach of my abilities; while the unlearned may incline to deem it a theme unfit for the exercise of a female pen.’

Besides John Parkhurst, the other male Epsom subscriber to The Song of Solomon was the Rev Martin Madan, who the previous year had raised considerable controversy with his publication of Thelyphthora; or a treatise on female ruin. In this Madan argued the social benefit of polygamy as a means of countering the evils of prostitution. He had been chaplain at the Hyde Park Corner Lock Hospital – a hospital for those afflicted with venereal disease – and may be considered to know of what he spoke. His treatise immediately attracted a series of ripostes. It was clearly a book – and, therefore, a subject much debated at this time and in the same 1 October 1781 letter to Hayley Mariana writes. Have you met with a book entitled ‘Whisper in the ear of the Author of Thelypthora’? The author Mr Greene did me the honor of sending it to me, and was it small enough to be enclosed in a frank, I would sent it to Earthham; tho I do not imagine it is a Book that would amuse either you, or Mrs Hayley much.’ Why, one wonders, did 40-year-old Edward Burnaby Greene send his work on this subject to 19-year-old Mariana Starke?

Besides John Parkhurst, the other male Epsom subscriber to The Song of Solomon was the Rev Martin Madan, who the previous year had raised considerable controversy with his publication of Thelyphthora; or a treatise on female ruin. In this Madan argued the social benefit of polygamy as a means of countering the evils of prostitution. He had been chaplain at the Hyde Park Corner Lock Hospital – a hospital for those afflicted with venereal disease – and may be considered to know of what he spoke. His treatise immediately attracted a series of ripostes. It was clearly a book – and, therefore, a subject much debated at this time and in the same 1 October 1781 letter to Hayley Mariana writes. Have you met with a book entitled ‘Whisper in the ear of the Author of Thelypthora’? The author Mr Greene did me the honor of sending it to me, and was it small enough to be enclosed in a frank, I would sent it to Earthham; tho I do not imagine it is a Book that would amuse either you, or Mrs Hayley much.’ Why, one wonders, did 40-year-old Edward Burnaby Greene send his work on this subject to 19-year-old Mariana Starke?

Greene was a translator and poet – though even in his lifetime not held in much regard – and at some time point his social or literary life must have intersected with that of Mariana to occasion this ‘honor’ . For, while the Ladies of Epsom may have been ignorant of the fact that they harboured a young Poet in their midst, her literary mentors were not – Mariana was in the custom of enclosing poems in her letters to Hayley. And to Hayley she made clear her feelings about Epsom society, writing at the end of a 7 January 1782 letter, ‘Pardon this hasty and stupid scrawl, as I am going to dress for an Epsom Party, the very thought of which, has benumbed my faculties.’ Both Mariana and her mother doubtless felt more stimulated at gatherings at which literature and ideas took precedence over discussions of hairdressing and caps. Not only did they utilise the circulating libraries but when in Town they made a point of visiting booksellers. In a letter to Mrs Hayley, dated 2 August 1781, Mrs Starke wrote, ‘Marian and I were at Dodsley’s the other day. The counter was covered by Mr Hayley’s poems, nothing sells so well. Dodsley did himself great credit with us, by his manner of speaking of Mr Hayley, second to none, now living, or that ever did live!’

Dodsley – whose shop was in Pall Mall – had recently published Hayley’s Triumphs of Temper, a didactic work illustrating the usefulness of a good temper to a young woman in search of a husband. See here for a Dulwich Picture Gallery page setting Romney’s portrait of Hayley alongside one of his illustrations from Triumph of Temper

Dodsley – whose shop was in Pall Mall – had recently published Hayley’s Triumphs of Temper, a didactic work illustrating the usefulness of a good temper to a young woman in search of a husband. See here for a Dulwich Picture Gallery page setting Romney’s portrait of Hayley alongside one of his illustrations from Triumph of Temper

The literary Epsom ladies maintained their interest in furthering the publication of interesting new works by women, subscribing to two important works of the period. In 1785 Millecent Parkhurst (‘Miss Parkhurst, Epsom’) and ‘Mrs Starke, Epsom’ were subscribers to Poems by Ann Yearsley, the Bristol milkwoman and protegee of Hannah More and in 1786 Mariana, her mother and Mrs Parkhurst were all subscribers to Helen Maria Williams’ Poems. The women may well have supported other publications, their connection not yet brought to light by the digital scanner. We can, however, be certain that these were two works that, along with The Song of Solomon, Hayley’s poems and that oddity, Whisper in the ear of the author of Thelypthora’?, were definitely on the shelves in Hyland House in the late 1780s. It was not to be long before Mariana, together with Millecent Parkhurst,- put her own pen into public action.

Sources: William Hayley Papers, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk

Copyright

Mariana Starke: Father is Worsted by Robert Clive

Posted by womanandhersphere in Uncategorized on September 20, 2012

Although Mariana Starke’s grandfather, John Starke, was never an employee of the East India Company, both his sons, Richard and John, were. Richard Starke (1719 – 93) – yet to be the father of Mariana – sailed from London in 1734 as a passenger in the Onslow to Fort St George, taking with him wine, a chest of apparel and an escritoire. In Fort St George he could have resumed contact with his mother’s family, the Empsons.

On 29 December 1735 Richard Starke entered ‘the service of the Honourable Co on the coast of Coromandel as ‘Writer Entertained’. A 1736 note made clear that it was ‘out of regard for his father’ that he was ‘taken into our service’, a 10 May 1737 dispatch confirming that ‘Mr Richard Starke is so usefull a hand in the Secretary’s Office’. During the following years his father sent out to him several boxes ‘of apparel’ and in 1746 ‘two boxes of books’, in 1747 one box of books and a hat, in 1750 one box of pamphlets and pens, in 1752 a box of books and in 1753 a pair of scales, a lanthorn and books. In April 1747 Richard was joined as a writer in the EIC by his younger brother, John Starke (aged 22), who sailed out on the Houghton with one chest, one escritoire, and a bundle of bedding

A dispatch from Fort St George to England, dated 22 February 1749, stated that Richard Starke, who had been ‘upper searcher at Madras – now appointed to that position at Cuddalore [i.e. Fort St David]. By 2 November 1749 he had been appointed ‘second’ at Fort St George – that is ‘under deputy governor’ and in February 1752 he succeeded Mr Prince as deputy governor of Fort St David, formally taking office on 31 July 1752.

Fort St David, about a mile from Cuddalore, was a small fortified town, near to the sea and, by all accounts, a very comfortable billet. In The Life of Lord Clive Sir George Forrest quotes the following description of the area: ‘The country within the boundaries is very pleasant, and the air fine, having seldom any fogs. In the district are many neat houses with gardens; the latter were laid out with much good taste by the gentlemen, who either had been, or were in the company’s service. These gardens produce fruits of different sorts, such as pine-apples, oranges, limes, pomegranates, plantaines, bananoes, mangoes, guavas, (red and white,) bedams (a sort of almond), pimple-nose, called in the West Indies, chadocks, a very fine large fruit of the citron-kind, but of four or five times it’s size, and many others. At the end of each gentleman’s garden there is generally a shady grove of cocoanut trees.’

Clearly it was all too comfortable to last. First we hear that John Starke, who was also working at Fort St David, under the Paymaster, received a peremptory dismissal for which no reason was given; a dispatch from London to Madras, 31 Jan 1755 merely noted: ‘The services of John Starke are dispensed with.’.’ Having no further occasion for the service of Mr John Starke he is upon receipt of this to be accordingly discharged from the Company’s service’.

A year later Richard Starke was compelled to write the following letter, dated 19 August 1756:

‘Honourable Sir and Sirs [to the President and Governors of Fort St George] I am to acquaint you that agreeable to your orders of the [lacuna] June I have delivered over the charge of the settlement of Fort St David to Col Robert Clive and as I imagine by the Company’s having been pleased to supersede me, by the appointment of that Gentleman so much my junior in their service, my conduct cannot have been so agreeable to them as I can assure Your Honour etc I have endeavoured to make it, I am to desire permission to resign their employ and return to Europe. Richard Starke.’

To the letter was subsequently appended a brief note: ‘In which the Board acquiesce’.

A dispatch of 21 November 1756 gave further information. ‘Starke handed over charge to Clive, returned to Madras in August, and requested leave to resign the service as he had been superseded by Clive.’ A further dispatch, 20 October 1757, gave a list of the passengers sailing to England on the Norfolk, among whom were Richard and John Starke.

Thus ended, rather ignominiously, Richard Starke’s Indian career, ousted by the very much more wily and ambitious Robert Clive. I am sure that a reading might be made of The Sword of Peace in the light of Mariana’s close knowledge of these events.

In 1759 Richard Starke married Mary Hughes, the 23-year-old daughter of Isaac Hughes, a merchant of Crutched Friars in the City of London, and Yewlands House, Banstead. Mariana, born in the last week of September 1762, was their first surviving child; I think a first son had died soon after birth. UPDATE (6 April 2014) I’ve just found a news report in ‘The Public Advertiser’ of 21 June 1762, to the effect that this young boy, aged 20 months, had died the previous week after falling out of the coach in which he was ‘taking an airing’ with some women servants and was then run over by the vehicle’s wheels.

Richard’s father, John Starke, died in a year later, in October, 1763. His will reveals some family dissension. Richard and his sister, Martha, appear to have been involved in a lawsuit, presumably involving John, the result being that, although John Starke left Hylands House at Epsom to Richard, the main part of his wealth was to bypass Richard, to be settled on Richard’s children. Thus, by the time she was a year old, Mariana Starke was living in a large, pleasant house in Epsom, where her father, who never again took up employment, could maintain a position in society on account of his Indian EIC service and, while probably not overburdened with great wealth, could live with a certain nabob style.

Copyright

Mariana Starke: Great-grandfather’s house

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on August 22, 2012

In the late-17th century Thomas Starke, the slave trader, lived and, I think, carried on his business in Mincing Lane in a house rebuilt in the 1670s – after the Great Fire of London. Starke’s house – and all the others in that street- have long since disappeared – now replaced by a Gotham City simulacrum, politely described as a ‘post-modern gothic complex’. However a few London houses built by Mincing Lane’s post-Fire-of London developer, Nicholas Barbon, do remain, including – pictured here – 5-6 Crane’s Court, just off Fleet Street – giving a rough idea of the manner of house in which Starke and his family lived.

Fortunately for us, when Starke – a freeman of the city of London – died in early 1706 several of his children were not yet 21 years old. This meant that the London Court of Orphans was required to draw up an itemized list of his household goods, assets and debts in order to supervise the division of the estate. This inventory provides a marvellous picture of the furnishing of the Mincing Lane house – at least some of which were purchased with the profits from Starke’s slave-trading activity, as well as an insight into Starke’s complicated finances. Moreover, the inventory, made on 18 April 1706, is held in the London Metropolitan Archives, very close to my home, a short walk collapsing the centuries.

Although the inventory does not reveal who was living in the house in 1706, a 1695 tax assessment showed that besides Starke, his wife, and two daughters, the household then comprised two apprentices (both of whom were to figure in later Starke litigation) and three servants – two of them women, one a boy.

The 1706 inventory begins at the top of the house – in the fore garrett – [perhaps a bedroom for the apprentices?] which contained:

One corded bedstead and rods, printed stuff curtains and valance, and flock bed and feather bolster and pillow, 2 blankets and 2 rugs, a table, 2 chests of drawers, a pallet bedstead, 2 chairs, one box – value £2 2s

I assume that ‘corded bedstead’ meant a bed with cords to support the mattress and that ‘rods’ are curtain-type rods from which hung the printed stuff curtains that surrounded the bed to exclude draughts.

The back garrett [perhaps a bedroom for 2 servants?] contained::2 chests, a horse for clothes, a few candles, 2 little bedsteads, a feather bed, 2 flock bolsters, two blankets, two rugs, a quilt, some lumber – value £2 1s

In the room 2 pairs of stairs forwards [perhaps Stark’s daughters’ room]: One sacking bedstead and rods, camblett curtains and valance lined with silk. Feather bed, a bolster, 2 pillows, 2 blankets, a rug, one counterpane. Corded bedstead and rods, curtains, 1 feather bed, bolster, 6 pillows, 4 blankets, a rug, 7 chairs, 1 chest of drawers, a table, 2 looking glasses, 5 window curtains, 3 rods, 2 pairs of dogs [ ie for the fireplace], a fender shovel, and tongs, a pair of bellows, 4 hangings of the room – value £15 7s.

Apart from the value, we can tell that this room was used by more important members of the household than the two garrets because of the use of ‘camblett’ to make the curtains, ‘camblett’ being a fine dress fabric of silk and camel-hair, or wool and goat’s hair, which was a lighter material, replacing broadcloth and serge and quite newly fashionable.. Similarly the lining of the valance with silk was a newish and fashionable furnishing style.

Back room: 1 corded bedstead, printed stuff curtains and valance, feather bed, bolster, 1 pillow, 1 blanket, a rug, 1 chest of drawers, 1 table, 2 matted chairs, grate, fender, shovel and tongs, a warming pan, a pair of bellow, 1 boll printed stuff. Hangings of the room, 3 chairs – value £5 2s

Middle room: 1 corded bedstead and rods, a pair of old curtains and valance, 1 feather bed, bolster, 1 pillow, a blanket and rug – value £1 15

In the room 1 pair of stairs backwards: [perhaps Starke’s bedroom – to be used for entertaining as well as sleeping.] 1 sacking bedstead, silk and damask curtains and valance lined with silk, a quilt and feather bed bolster, some calico curtains, 1 table, a looking glass, 6 chairs and cushions, a slow grate, shovel, tongs and poker, a brass hearth shovel and tongs, 3 pairs of tapestry hangings – value £36 6s [Peter Earle in The Making of the English Middle Class: Business, Society and Family Life in London 1660-1730 (1989) gives the average value of the furnishings of a merchant’s bedroom as £23.3, positioning Starke’s as rather above average.]

The silk and damask curtains and the valance lined with silk were smart and fashionable, while the presence of the tapestry hangings suggest a room intended for comfort in a slightly old-fashioned style..

On the staircase: 3 pictures, clock and case, 2 sconces – value £5

In the Dining room [Earle denotes the dining room as the ‘best’ living room in a house of this type, giving the average value of the contents of such a room as £12 2s – making Starke’s furnishings a little above the average in value.]: Gilded leather hangings, 2 tables, a looking glass, 1 side table, 11 cane chairs, 12 cushions, a pallet case, 2 glass sconces, a pair of tables, brass hearth dogs, shovel and tongs – value £13 12s.

The gilded leather hangings were, by the early 18th-century, perhaps a little old fashioned, but the possession of cane chairs marked the Starkes out as a family who were prepared to buy new and fashionable styles. Cane chairs had been new in aristocratic homes in the 1660s, and were taken up by ‘middling men ’ from the 1680s. It would seem that the Starkes’ cane-bottomed chairs required cushions to make them acceptably comfortable.

In the parlour [the ‘second best’ living room]: Cane chairs, 2 cushions, a boll – value £2 10s.

In the Kitchen: An iron back grate, fender, 2 spit racks, an iron crane, 3 hooks, 2 shovells, tongs and poker, 1 gridiron, 2 iron dripping pans, 2 dish rings, 1 shredding knife, 2 frying pans, 2 box irons and heaters, jack chain and weight and pulley,. 4 spits, a beef fork, a brass mortar and pestle, 7 candlesticks, a pair of snuffers, a ladle and scummer, 2 iron bottles, 4 brass pots and covers, 1 bottle, 2 sauce pans, 1 copper stew pan, 3 chairs, 2 folding boards, 1 pair of bellows and napkin press, a table, a lanthorn, 196lbs of pewter, some tin wooden and earthenware – value £19 12s 10d .

Earle mentions that the average value of kitchen goods in this period was between £10-£20, putting the Starkes’ batterie de cuisine at the top end of the scale.

In the cellar and yard: A few coals, a beer stilling, 2 brass corks, some fire wood, a leaden cistern, 1 boll, 2 doz glass bottles – value £7 1s.

The inventory goes on to give the value of Starke’s wearing apparel (£5), household linen, and plate (292 oz, value £74 –presumably including the silver salver and caudle cup that Starke specifically mentioned in his will) – before moving on to monies owed to him and his own debts.

All in all, this is a house of a middling London merchant, one who, with his family, wished to be comfortable but was not desperate to adopt the very newest fashions. I do not think it would have been as elegant as the parlour room set, dating from 1695, that one can see at the Geffrye Museum. Here you can see the Starkes’ cane chairs, but Thomas Starke presumably preferred the older-fashioned tapestries and gilded leather hangings. which many of his fellow merchants – as in the Geffrye Museum re-creation -would have been taking down and replacing with pictures. In fact only three pictures are listed in the Starke inventory, all hanging on the stair case, alongside the household’s only clock. Similarly, the Starkes were, presumably, still eating off pewter and had not been tempted by the more newly fashionable china.

I did find two omissions interesting. The first is that no room is specifically denoted as a counting-house, although at the time of Starke’s death the sum of £245 19s 13/4 [=£32,000 purchasing power in today’s terms] was held in cash in the house. So, perhaps I was incorrect in assuming that, as he was living in Mincing Lane, in the very heart of the trading district, his business would have been done on the premises. And, secondly, I suppose I might have expected a merchant’s possessions to have included at the very least a quantity of ledgers – and, perhaps, some books and a globe.

Sometime after Thomas’ death, his widow and her daughters – Sarah, Martha, Frances and Elizabeth moved out of the City. There no longer being any necessity to live close to business, they chose Chelsea as their new home– more rural, more fashionable. It is possible that they were the first occupants of a newly-built house in Upper Cheyne Row, close to their great friend Lady Mary Rawlinson, widow of a a close associate of Thomas Starke and a former Lord Mayor of the City of London. The Survey of London suggests that this house and its immediate neighbours were built c 1716 and Lady Mary and her daughter, also Mary, lived at 16 Upper Cheyne Row between 1717 and her death in 1725. Between 1748 and 1757 Thomas Starke’s daughter, Martha, and the younger Mary Rawlinson lived together at 12 Upper Cheyne Row. They were evidently very close; in her will Martha, who died in 1758, left everything to Mary and asked to be buried with her in the same grave in Ewell parish churchyard. However, Mary Rawlinson lived on to 1765 and in a codicil to her will, made in 1764, changed her preferred place of burial from Ewell to the Rawlinson family vault in St Dionis Church Backhurch in the City (demolished 1868)..

I imagine that Thomas Starke’s tapestries and gilded leather hangings did not make the move from Mincing Lane to Chelsea and that his widow and daughters took the opportunity to furnish the new – airier and lighter – house with new china and new materials to complement the modern fireplaces and panelling. As we shall discover, in the early 18th-century the Starke family began a close association with India and goods – gifts – from the East would have travelled back to decorate these Chelsea rooms, perhaps, eventually coming into the possession of Mariana Starke.

Copyright

Mariana Starke: Great-grandfather’s will

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on August 8, 2012

I am interested in trying to build up a picture of the physical reality of the lives of Mariana Starke and her forefathers.

Although it is well nigh impossible to know what memory, if any, of Thomas Starke, slave trader, descended to his daughter, Mariana Starke – she, the ‘celebrated tourist’, was born a little under 60 years after his death – I wondered if links might be discerned through a tracing of worldy goods as they descended through the family. I made a start with Thomas Starke’s will. Through this, at the very least, we become acquainted, more closely than in any baptism register, with his surviving children and with the friends – fellow merchants – to whom he entrusted the will’s execution.

‘To my dear & loving wife Sarah one full third part of all my personal estate ..if estate does not amount to sum of £2000 [2012: £ 261,000] leaves to Sarah all my estate in co of Suffolk lying in the hundreds during her natural life and after to my son John Starke and his heirs forever. But if one third part shall amount to £2000 then my will and mind is that the said estate shall immediately go to said son. I likewise give to my wife all her jewels ? of gold and her gold watch and a large silver salver and caudle cup and cover. I give unto my son John Starke and to his heirs for ever all my reall estate in Virginia consisting of 5 plantations. I give to my said son the sum of £500 and the diamond ring I wear. I give unto my loving daughter Mary Sherman the sum of £200 and likewise forgive her all such sums of money as she stands indebted to me for. I give to my said son John Starke a full one fifth of my personal estate after my just debts are paid and my wife’s one third part deducted. I give to my loving daughter Sarah Starke the sum of £300 and also one fifth part of all my personal estate [etc] provided that said one fifth part shall not exceed the sum of £1500 [2005: £209,000] and what shall appear to be more than that sum I give unto my said son. I give to my said daughter Sarah all her jewels and my gold watch and 2 brooch [?] pieces of gold which were my Aunt Dennis’s. I give to my loving daughter Martha Starke the full one fifth part of my personal estate [etc]. I give unto my loving daughters Frances and Elizabeth unto both of them the full fifth part of my personal estate [etc]. I give unto my daughter Sarah a large gilt spoon. to Martha one ?? of gold that was my Aunts and I give to Frances one old Nobb (?) spoon. I give to Francis Lee and William Downer the sum of £10 apiece to buy them mourning and a ring of 20s value and I desire them to be aiding and assisting my wife and son. And my will is that my daughters’ legacy shall be paid them as they shall arrive to the age of 21. And make my wife and son jointly my executors and appoint my said loving friends Francis Lee and William Downer to be the overseers of my will.

30th Jan 4th yr of Ann (1706)

Witnessed by Ann Stephens, W. Ford, John Hodgkin, Jeffery Bass (?) Probate 4 March 1706.

So, even from this cursory transcription of the will, we can visualise Thomas Starke’s most prized – or most expensive – possessions – the jewellery, gold and silver – the salver and the caudle cup – and know that he still held five Virginia plantations. In the next ‘Mariana Starke’ post I will be able to reveal vastly more of the possessions with which Thomas Starke was surrounded as he lay on his death bed in the house in Mincing Lane.

Copyright

What Mariana Starke’s Great-Grandfather Was

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on August 1, 2012

Mariana Starke’s great-grandfather was a Virginia landowner and slave trader.

A slave shackle recovered from Thomas Starke’s ship.

In the last ‘Mariana Starke’ post I gutted the red herring that had Mariana born in India. This, if a red herring could be said to be put to such a use, had been a hook on which some scholars had hung critiques of her two India-set plays. While I am certain that an interest in Anglo-Indian affairs permeated Hyland House, which had been purchased with the proceeds of her grandfather’s engagement with India, I am wondering if the shade of Thomas Starke, her great-grandfather, did not also, perhaps, linger? If so, that may well give an added spice to the abolitionist sub-plot of The Sword of Peace (1788) and to two of Mariana’s creations in it, the slaves Caesar and (offstage) Pompey.

Thomas Starke (c 1649-1704), was probably born in Suffolk and in the early 1670s spent some time in Kings and Queens County, Virginia, where he (and perhaps another member of his family) owned land – land devoted to tobacco production. On his return to England he married Sarah Newson, possibly in 1676 at Pettistree in Suffolk. Those facts are interesting – if a little hazy – but what is definite is that by 1678 the family was living in London, in the parish of St Dunstan in the East, where a son was christened. Their surviving children – several died in infancy – included Mariana’s grandfather, John (1685-1765) and several daughters, some who were to make alliances with fellow merchant families.

The Starkes lived in Mincing Lane, in a house built after the recent Great Fire. The premises also served as Thomas’ counting house; I will relate more of this interesting establishment in a subsequent post.

The counting house was the hub of Starke’s business empire; he is first recorded as importing tobacco (24,252lb) from Virginia in 1677. Many of the records regarding his business may be found here. The ships plying the Atlantic to pick up the tobacco did not, of course, travel empty, but carried over a wide variety of goods to tempt the settlers. On 10 October 1677, one of Starke’s ships – the Merchant’s Consent – set sail for Virginia carrying, amongst other consignments, 2 cwt nails; 10 lbs Norwich stuffs; 5 doz Irish hose; 35 lbs wrought brass; 1 cwt hops; 1 small saddle; 3 castor, 2 felt hats; 3/4cwt haberdashery wares (to a value of 4s 6 1/2d) . On another occasion Starke’s consignment included ‘Indian cargo’ – that is tomahawks to sell to Indians – plus clothing, hardware, flints and gunpowder.