Woman and her Sphere

Posts Tagged matilda hays

La Bella Libertà: English Women Writers and Italy

Posted by womanandhersphere in Women Writers and Italy on May 15, 2017

A curious incident that occurred – or, rather, didn’t occur – a couple of days ago reminded me of a past link I effected between Persephone Books and English women writing about Italy. For, many years ago, I gave a talk on this subject at a symposium organised by Persephone at Newnham College. I have in the past posted a few articles on my website amplifying some of the material covered – but here below is the fons et origo.

We have to imagine the subject of one of Persephone’s latest books [Flush] curled up on the sofa alongside his mistress in the drawing room at Casa Guidi in Florence. It’s early evening and the long shutters have been opened, letting dusky light into the somewhat cavernous drawing room. Flush is startled by a sudden movement as his mistress puts aside her book, raises herself from a reclining position and takes a few steps over to the open window. They both venture out onto the narrow balcony, facing the imposing wall of the church, opposite across the narrow road. While Flush is involved with Flush business, Elizabeth cranes over the railing, to catch a glimpse of a young boy as he passes, singing, along the street below. It is the essence of his song that I have lifted to name this talk. This is how Elizabeth Barrett Browning put into words her experience that evening:

‘I heard last night a little child go singing

‘Neath Casa Guidi windows, by the church,

O bella libertà, O bella – stringing

The same words still on notes he went in search

So high for, you concluded the upspringing

Of such a nimble bird to sky from perch

Must leave the whole bush in a tremble green,

And that the heart of Italy must beat,

While such a voice had leave to rise serene

‘Twixt church and palace of a Florence street’

Thus in Under Casa Guidi Windows, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, one of England’s most famous exports to Italy, extolled ‘La Bella Libertà’, the freedom that was Italy’s due. However it takes only a cursory reading to realise that ‘sweet freedom’ was what above all Italy gave to the many English women writers who have, over the last two centuries, flocked there.

As we can recognize, ‘freedom’ is not synonymous with ‘bliss’, but in Italy English women have felt free to fail as well as succeed – to be unhappy as well as happy – at least to be unhappy in their own way. They have felt able in that country, far from home, the Alps a psychological as well as a physical barrier, to construct a life for themselves, untramelled by the conventions that controlled society in England. One would think that nowadays such escape would no longer seem necessary. But nobody can fail to have noticed the recent spate of books by women – not only British women, but also Americans and Australians – describing new lives forged in Italy. These are merely the latest in a line of such love affairs with Italy that stretches way back into at least the 18th century. Indeed, Italian-American women (that is women whose parents or grandparents left the mother country – usually the poor south – for the US) have produced so many works recounting their return that a school of literary criticism is being developed to discuss the phenomenon. And guess what these writers call themselves? – yes, Persephone’s daughters. Persephone, whom the myth relates was snatched from the fields of Enna in Sicily, has become a particularly appropriate symbol for such women who travel in order to reconnect with their ancestral heritage and discover a new identity. Because of patterns of emigration English women are far less likely to have this experience of searching for Italian roots. Rather, individually, they set forth for Italy to root themselves. I know – my own daughter has done so.

What follows is a series of vignettes of the lives of English women writers shaped by Italy. Apart from marvelling at the bella libertà these women, in a myriad of ways, found, I have no particular thesis but have allowed myself – and I hope – you -the pleasure of glimpsing a diverting eclectic range of women and of experiences in Italy.

There are two early books by women that piqued my interest. The first, Travels in Italy between the years 1792 and 1798, (published in 1802) is by Mariana Starke, who when she began her Italian travels was 30 years old. Travels in Italy evolved into the first modern guide to the country or, indeed, at least in English, to anywhere. For those who had previously undertaken and written of the Grand Tour had not burdened themselves of the precise – or, doubtless, even a vague – knowledge of the price to be paid for washing petticoats in Pisa, buying wax candles in Venice, asses milk in Tuscany, or hiring carriages in Florence. It took a woman, and a woman conscious of value for money, to gather and set out all these – and a thousand more fascinating details – of life as a traveller. She gives a very lengthy list of the equipment it is necessary to take – from a chamber pot that could be fitted into the well of a coach to a nutmeg grater – and goes into considerable detail about how to get across the Alps – this at a time before Napoleon for his own purposes had constructed a manageable road. She describes what type of coach was suitable and how it had to be taken apart, laden onto mules and its passengers then carried in sedan chairs over the mountain pass by porters. The book covers all the major towns of Italy, giving details of the best lodging houses, restaurants, doctors, dentists, provision merchants, dress makers and tailors, and details of all the principal sights.

Mariana Starke introduced an innovation into travel writing, annotating particular buildings and paintings with exclamation marks to indicate merit – five, I think, for the best. She wanted the visitor, if pressed for time, to select only the best – and set out a daily itinerary in order to ‘prevent Travellers from wasting their time and burdening their memory by a minute survey of what is not particularly interesting, and thereby, perhaps, depriving themselves of leisure to examine what really deserves the closest attention.’ Doesn’t that sound the advice of one who knew what it was to have been dragged around one gallery too many?

In the late 1820s Mariana Starke was taken up by John Murray and wrote for him a guide to the whole Continent – her exclamation mark system being now exchanged for a system of stars. So when you next consult your Egon Ronay or Good Food Guide, it is Mariana Starke you have to thank for inventing the tools of discrimination. [For more on Mariana Starke see here].

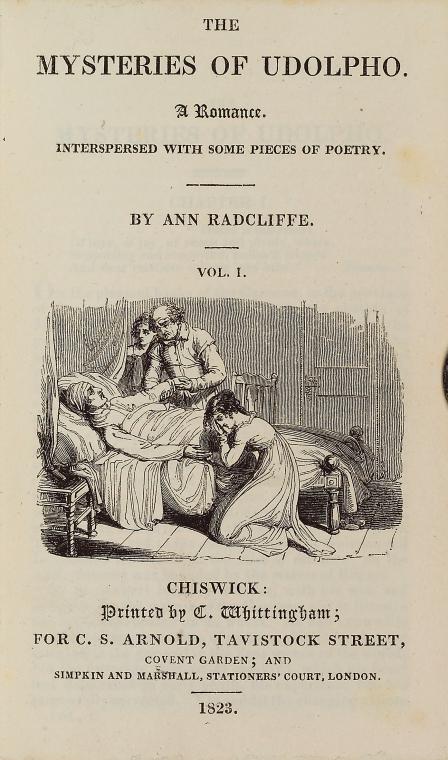

My second book is a novel – Anne Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho, published in 1794, at a time when Mariana Starke was well into her travels, and which captivated the British reading public – particularly its female portion – painting Italy as picturesquely gothic. The irony is that this romantic view of Italy was shaped by a woman whose continental travels never extended further than Holland and Germany, and then only after the success of her Italian novels. Her landscape descriptions were drawn from travel literature and from the work of mid-17th century Rome-based painters such as Claude Lorraine, Poussin and Salvator Rosa. Her descriptions in turn had an overwhelming influence on the way that Italy was seen by later travellers. Northanger Abbey, published in 1817, is, of course, a delicious parody of her subject matter and style.

Whereas Mariana Starke, having detailed the nitty gritty of passing across the Alps, gives us no description of the scenery, Mrs Radcliffe in Udolpho more than makes up for this. ‘The snow was not yet melted on the summit of Mount Cenis, over which the travellers passed; but Emily [our heroine], as she looked upon its clear lake and extended plain, surrounded by broken cliffs, saw, in imagination, the verdant beauty it would exhibit’ – .’ who may describe her rapture, when, having passed through a sea of vapour, she caught a first view of Italy; when from the ridge of one of those tremendous precipices that hang upon Mount Cenis and guard the entrance of that enchanting country, she looked down through the lower clouds, and, as they floated away, saw the grassy vales of Piedmont at her feet.’ This is Arcadia.’

Whereas Mariana Starke, having detailed the nitty gritty of passing across the Alps, gives us no description of the scenery, Mrs Radcliffe in Udolpho more than makes up for this. ‘The snow was not yet melted on the summit of Mount Cenis, over which the travellers passed; but Emily [our heroine], as she looked upon its clear lake and extended plain, surrounded by broken cliffs, saw, in imagination, the verdant beauty it would exhibit’ – .’ who may describe her rapture, when, having passed through a sea of vapour, she caught a first view of Italy; when from the ridge of one of those tremendous precipices that hang upon Mount Cenis and guard the entrance of that enchanting country, she looked down through the lower clouds, and, as they floated away, saw the grassy vales of Piedmont at her feet.’ This is Arcadia.’

Whereas Mariana Starke said of Venice only that ‘from its singularity alone [it] highly merits notice’ and that ‘it is less strikingly magnificent than many other cities of Italy‘, in Udolpho ‘nothing could exceed Emily’s admiration on her first view of Venice, with its islets, palaces, and towers rising out of the sea, whose clear surface reflected the tremulous picture in all its colours…the sounds seemed to grow on the air; for so smoothly did the barge glide along, that its motion was not perceivable, and the fairy city appeared approaching to welcome the strangers.’ It was Mrs Radcliffe’s view of Italy as arcadia and fairyland, albeit with a gothic tinge, that inspired the dreams of so many English women travellers in the early 19th century – and it is those who wrote who have immortalized their dreams. However, if these women held Mrs Radcliffe in one metaphorical hand, they held Mariana Starke’s guide book in the other. It was her details, perhaps prosaic then, but utterly fascinating now, that gave a reality to the dream – women could work out how, and how to afford to, to travel to arcadia.

All these features –an appreciation of the gothic and the arcadian and fairyland nature of Italy– resonated through the work and lives of the English women I shall discuss.

Lady Elizabeth Foster

My first vignette is of a woman whose early Italian travels, undertaken in the last quarter of the 18th century, are the stuff of the gothic novel and whose later, 19th-century life, was devoted to uncovering the arcadia of classical Italy. Her whole life is something of a fairy tale. While not a published writer, Lady Elizabeth Foster commended her daily experience to 128 volumes of journals, excerpts of which have been used in recreating both her life and that of her dearest friend, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. A biography of Georgiana has in recent years received almost as much media hype as did the works of Mrs Radcliffe at the end of the 18th century, so some of you may well know something about her life. However, its dramas and excesses pale into insignificance beside those of her ‘Dearest Bess’. Lady Elizabeth’s ‘sweet freedom’ lay in being her loveable, incalcitrant, self-indulgent self and Italy allowed her to be so. She married young but after five years separated from her husband who consequently forbade her to see their two sons, whom she didn’t meet again for a further fourteen years – but who still remained devoted. Returning to England from the marital home in Ireland, she cast her spell on the Devonshire House circle. In fact the circle became a triangle when Lady Elizabeth, while remaining the Duchess’s most intimate friend, in the autumn of 1784 also became the lover of the Duke. Unsurprisingly she soon became pregnant; surprisingly there was no hint of any scandal as she took herself off to Italy, from whence she had only very recently returned. By April 1785, keeping up her diary, which served as a confessional, Lady Elizabeth was in Pisa, Florence, and then Rome, where she wrote ‘Sometimes I look at myself in the glass with pity. Youth, beauty, I see I have; friends I know I have; reputation I still have; and perhaps in two months, friends, fame, life and all future peace may be destroyed and lost for ever to me. If so, my proud soul will never, never return to England –But it was not his fault. Passion has led us both awry – his heart suffers for me I know’. Entries such as this – and there are very many more – would not disgrace a gothic novel.

After a stay in Naples, at the end of June she was accompanied to Ischia by her brother, Jack Hervey, himself something of a rake, who was living a racketty life at the Naples court and, like everybody else, was quite oblivious of her condition. She had thought the island suitably remote and settled there to await the birth, but after a couple of weeks discovered that friends from Naples were coming to the island and that she would no longer be able to conceal her condition – and disgrace. She now revealed her predicament in a letter to her brother, who hastily returned to Ischia and appears to have been entirely supportive, although ‘I could not – dared not name the dear Author of my child’s existence’ Jack told her she would have to leave Ischia and, with her faithful servant, Louis, they set sail for the mainland in an open boat. ‘How calm the Sea is – it scarce is heard as it beats against the rocks, the air is perfum’d with herbs, the sky is clear, at a distance blazes Vesuvius – oh were I happy’.

They landed at Salerno and then travelled to nearby Vietri, a little town now swallowed up in greater Salerno. When, many years ago, I read the following entry from her journal – written over 200 years before that – it made an impression such that I have never forgotten it . ‘With no woman at hand, encumbered by the weight of my child, enfeebled by long ill health, fearing every person I met, and, for the first time in my life, wishing only to hide myself, I arrived at last.’ The place to which brother Jack directed her appears to have been at best a kind of baby farm, at worst a brothel – perhaps a bit of both. Her description of the ‘seraglio’, as she called it, is gothic –run by ‘The Arch-Priest of Lovers, his woman-servant, a coarse, ugly and filthy creature, the doctor (his brother) and his wife, two young girls, pretty enough but weeping all day, the nurse who was to take charge of my child; and some babies which cried from morning to night.’ One wonders quite how it was that it was her brother knew of this place. She passed as Louis’ wife, as a servant’s wife dishonoured by Jack Hervey. A few days later a daughter was born and, as so often in gothic novels, the heroine now showed resilience in a time of extremity. Thinking her attendants quite ignorant, she immediately took care of the new-born baby but then, instead of the usual lying-in period of a month or so, which she had enjoyed after the birth of her previous children, was back on the road after six days, leaving the baby behind, eventually arriving at her brother’s house at Naples. Louis later fetched the baby, Caroline, from Vietri and brought her to Naples – where she was looked after by foster parents. I always thought this a memorably Italian episode.

Georgiana died in 1806 and in 1809 Lady Elizabeth married the Duke. He died in 1811 and in 1815, after peace had returned to Europe, Elizabeth, now Dowager Duchess of Devonshire returned to Italy, living in Rome until her death in 1824, keeping a very elegant salon, packed with diplomats, painters and sculptors. During her earliest visit to Italy in 1784 she had described in her journal, with impressive diligence, the paintings and antiquities she had seen. Now, in this new stage of life, she really did become a lady of letters, commissioning de luxe editions of Virgil and of Horace. She took up antiquities, under the guidance of Cardinal Consalvi, her last love, secretary of state and spy master to Pius VII. Of her excavating, Lady Spencer, the sister-in-law of the first Duchess, wrote ‘That Witch of Endor the Duchess of Devon has been doing mischief of another kind to what she has been doing all her life by pretending to dig for the public good in the Forum’. Mrs Charlotte Ann Eaton, who had travelled to Italy with her brother and sister and published her observations in 1820 as Rome in the Nineteenth Century, commented apropos the reclamation of the Forum, ‘the English, as far as I see, are at present the most active excavators. There is the Duchess of D— at work in one corner, and the Pope, moved by a spirit of emulation, digging away in another’. Italy had certainly allowed Lady Elizabeth the freedom to develop in ways she found unconventionally satisfying.

Charlotte Eaton’s sister, Jane Waldie, also published her description of their journey, albeit with a different publisher, and her enthusiasm still leaps off the page – when ‘the dome of St Peter’s burst on our view in the midst of the Campagna. Unable any longer to restrain ourselves, we leaped out of the carriage and ran up a bank by the road-side. Never, oh, never, shall I forget the emotions with which I gazed on this prospect! That Rome itself should really be before me seemed so incredible, that my mind could scarcely take in the fact.’ She and Charlotte stayed first at the Hotel de Paris in the Via della Croce, which runs off the Piazza di Spagna in the heart of the ‘English’ quarter, but didn’t remain there long – on the second night of their stay the chimney of one of their apartments took fire and they moved to lodgings in the Corso. [For more about Charlotte Eaton see here and here.]

In fact the Hotel de Paris, or Villa di Parigi or Albergo di Parigi as they variously term it, provided shelter to a series of our English women writers over the next 20 years. [For more about the Hotel see here.] It is slightly surreal to see their shades slipping into bed, one after the other, under this one Roman roof. Amusingly all commented on the indifference of its facilities. It was at the Villa di Parigi in the summer of 1819, while the Duchess of Devonshire, the sole survivor of her menage à trois, was still digging in the Forum, that another interesting trio took up abode in Rome. Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife, Mary, daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, were accompanied by Mary’s step-sister, Claire Clairmont. All three sought inspiration from Italy and freedom from censure and their past –which was already gothic both in life (Mary’s half-sister, Fanny, and Shelley’s wife, Harriet, had both recently committed suicide) – and literature – Mary Shelley had just published Frankenstein. The drama of their stay in Italy was to be remorseless.

Curran, Amelia; Claire Clairmont (1798-1879); Newstead Abbey. http://www.artuk.org/art. works/claire-clairmont-17981879-47805. Amelia Curran was a friend of Marianna Starke.

Claire Clairemont, who had devoured Mrs Radcliffe in her exhaustingly wide-ranging reading, wrote in her journal of the descent from Mont Cenis that ‘The primroses are scattered everywhere. The fruit trees covered with the richest blossoms which scented the air as we passed. A sky without one cloud – everything bright and serene – the cloudless Sky of Italy – the bright and the beautiful’. Thus she entered Arcadia. But with Shelley and Mary, and their two young children, William and Clara, she was travelling to hand over her daughter, born the previous year when she was 19, to the child’s father, Lord Byron. This was done in April 1818, at Venice, and in August she received permission from Byron to visit the child. She persuaded Shelley and Mary to accompany her, although Mary was very reluctant because baby Clara was unwell, To Mary’s great grief, as soon as they arrived in Venice, Clara died. ‘Sweet freedom’ was not without its dangers – the story of English women in Italy is littered with lost or dead babies. The mother with a secret and – often related – the orphan – are recurring themes in gothic novels.

The Shelley party later travelled to Rome and the Villa di Parigi. Claire appears, like all good travellers, to have been planning a book about Rome. Mary, who in the 1840s did publish a book on her later Italian travels, also at this time recorded her impressions of the city, ‘The other night we visited the Pantheon by moon light and saw the lovely sight of the moon appearing through the round aperture above and Lighting the columns of the Rotunda with its rays…’ But there was little time for sight seeing – tragedy had not done with them. On 7 June, despite having moved from the Villa di Parigi to an apartment at the top of the Spanish Steps, where the air was thought to be less malarial, the Shelleys’ two-year old son, William, died of Roman fever and was subsequently buried in the Protestant cemetery. He is a doubly lost English baby because when, all too soon, his grave was unearthed in order to bury him near his father, the grave marked as his was found to contain not a baby but the remains of an adult. The year after William’s death Mary wrote a verse drama for children, heartrending when one knows what she had recently suffered. It is, what else, but Proserpine’ – filled with Ceres’ anguished search – ‘Where is my daughter? Have I aught to dread? Where does she stray..I fear my child is lost’. Two years later Claire’s daughter, Allegra, died, a five- year old banished by her father to a convent, bereft of her mother’s care – and a couple of months after that Shelley was drowned off the Ligurian coast.

Mary remained in Italy until 1823 but was back in England when, in 1826, she proposed writing a review article based on a handful of books that had recently been published by English writers about Italy. One of the books she reviewed was The Diary of an Ennuyée, published anonymously and purporting to be the diary of a young governess, travelling in Italy with her charge, but broken-hearted, having left a shattered romance behind in England. Indeed so broken-hearted was she that at the end she goes to her grave. However, although there was much that was true in the book, its author, then Anna Murphy, but who, soon after her return to England, became Mrs Anna Jameson, had not in fact died, but was at the very beginning of a long and distinguished writing career, in which Italy played a central part. Indeed the Diary of an Ennuyée, in the intervals between anguished breast-beatings, serves as a very detailed guidebook to Italy, particularly Rome. A guidebook, admittedly, that veers more towards Mrs Radcliffe than Mariana Starke. It contains little in the way of practical details, such as routes and prices, but her descriptions do have the merit of being based on personal observation.

Anna Murphy’s first day in Rome strikes as true a note as did Jane Waldie’s description of her arrival: ‘The day arose as beautiful, as brilliant, as cloudless, as I could have desired for the first day in Rome. About seven o’clock, and before any one was ready for breakfast, I walked out; and directed my steps by mere chance to the left, found myself in the Piazza di Spagna and opposite to a gigantic flight of marble stairs leading to the top of a hill. I was at the summit in a moment; and breathless and agitated by a thousand feelings, I leaned against the obelisk, and looked over the whole city.’ She was here standing a few yards away from where young William Shelley had died barely five years previously. And, yes, her party was staying at the Albergo di Parigi.

Having spent an adventurous 20 or so years – she travelled extensively around north America and Canada, having ditched her alcoholic husband, and earning a living through her writing – Anna Jameson returned to Italy in 1846 under rather romantic circumstances. It was she who conducted Mr and Mrs Browning from Paris to Pisa. She was as surprised as the rest of the world at the Browning marriage. When she was contacted in Paris she had only a few days previously bade farewell to her friend Elizabeth Barrett in Wimpole Street, having no inkling of the planned elopement. Anna was on her way to Italy to research a new book, Sacred and Legendary Art, and was delighted to act as courier for the impractical pair. From Paris she wrote to her sister ‘I have also here a poet and a poetess – two celebrities who have run away and married under circumstances peculiarly interesting, and such as render imprudence the height of prudence. Both excellent; but God help them! for I know not how the two poet heads and poet hearts will get on through this prosaic world.’. She later commented that the elopement ‘was as delightful as unexpected, and gave an excitement to our journey which was already like a journey into the old world of enchantment – a revival of fairyland.’

Italy indeed had a magical effect on Elizabeth Browning. While on the journey Mrs Jameson wrote to her sister from Avignon ‘Our poor invalid has suffered greatly, often fainting and often so tired that we have been obliged to remain a whole day to rest at some wretched place..’ But as Flush noted (courtesy of Virginia Woolf), after their arrival in Pisa ‘she was a different person altogether. Now, for instance, instead of sipping a thimbleful of port and complaining of the headache, she tossed off a tumbler of Chianti and slept the sounder..Then instead of driving in a barouche landau to Regent’s Park she pulled on her thick boots and scrambled over rocks. Instead of sitting in a carriage and rumbling along Oxford street, they rattled off in a ramshackle fly to the borders of a lake and looked at mountains…Here in Italy was freedom and life and the joy that the sun breeds.’ Indeed, breeding began as soon as she reached Pisa, although she miscarried five months later. Rather than lamenting this loss, she was very proud of having been pregnant at all. After a recuperating stay in Pisa, a city that had for many years been host to an interesting, rather Bohemian English set, all escaping one thing or another, the Brownings travelled on to Florence in the summer of 1847, eventually moving into an apartment in Casa Guidi.

It was here in Florence, having never previously been particularly interested in national politics – although she had long been concerned with social reform – that Elizabeth took up the cause of Italian freedom. On a more prosaic level for the first time she was able to experience other aspects of her freedom – she furnished her first home and in 1849, following a second miscarriage – and when she was 43 years old – she gave birth to a son.

This is the view I remember from the Casa Guidi balcony. I no longer have a photo of my own so this is taken from mildaysboudoir blogspot – with thanks.

Two years later, in 1851, she published Under Casa Guidi Windows, in which she charts her initial optimism that the newly awakened liberal movements would result in the freedom and unification of the Italian states and, then, her disillusionment when the movement was crushed. Biographers have suggested that she equated the oppression of the Italian people (most of Italy was then under Austrian rule) with that of her father against her. Whether or not there is any truth in this analogy – it has a rather depressingly contrived feel – there were other English women – some of whom had certainly grown up happily in the bosom of supportive families – who were also intensely interested in the cause of Italian freedom.

One such was Jessie White, born in Gosport in Hampshire where her father had a ship building firm, and who i 1854, when she was 22, met Garibaldi in London. She was no conventional young lady, having already studied for a time in Paris and was at this time writing for Eliza Cook’s Journal, a London-based feminist publication. Garibaldi fired her with enthusiasm and she travelled to Italy, where she met Mazzini and became a disciple.

Mazzini appears to have had this effect on women –at least on English women. Another of his devotees was Emilia Ashurst, known at this stage of her life as Mrs Sidney Hawkes, a member of a London family all of whom involved themselves in the radical causes of the day. When Jessie White returned to England in 1855, she met Emilie, who had already had many Italian adventures. Besides acting as his secret agent Emilie wrote a memoir of Mazzini and translated his works into English. She was also an artist and a copy of her portrait of Mazzini, enigmatically labelled as by ‘E. Hawkes’, is on display in the Museo di Risorgimento, housed inside the Victor Emmanuel monument in Rome. It struck me when I saw it that, as visitors drifted past it year after year, there could hardly be among them anybody who would realize that behind this painting lay an Englishwoman’s deep commitment to Italy. Emilie separated from Hawkes and later married Carlo Venturi, a Venetian patriot, who proved an altogether more satisfying husband.

Jessie White, too, wished to give practical aid to Italy. She thought she would train as a doctor in England, but, as a woman, she was refused admittance to medical school, and she settled on offering herself as a nurse to the Italians and also, as had Emilie Venturi, concentrated on translating Italian works of propaganda and writing articles for the English press. In 1857 she took part in an uprising led by Mazzini and was arrested and imprisoned. In prison she met Alberto Mario, like Venturi a handsome Venetian, whom, on their release, she married. In the early 1860s, with her husband, she followed Garibaldi and his men, nursing the sick – for most of the time the only woman attached to the campaign. From 1866 until her death in 1906 Jessie White Mario, as Italian correspondent of the Nation, analysed Italy for American and English readers. She travelled all round Italy in search of material for articles and is now esteemed in Italy as one of the first of its investigative reporters, writing about economic developments and social conditions – especially in the south –her writing forceful in detail, vivid and vigorous. When she died in 1906 one paper connected two Anglo-Italian patriots, specifically remarking that her funeral procession in Florence, ‘passed the Casa Guidi, which was decorated in honour of the centenary of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’.

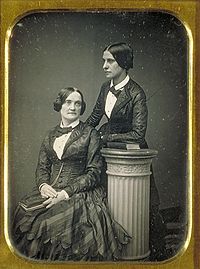

Amongst the artefacts now displayed in Casa Guidi is a cast of the clasped hands of Robert and Elizabeth Browning. The sculptor of this incarnation of romance was a young American woman, Harriet Hosmer. Harriet had lived and worked in Rome since 1852, part of a group of ‘jolly female bachelors’ that clustered around the overpowering personality of the American actress, Charlotte Cushman. After meeting Charlotte with her companion, Matilda Hays, Elizabeth Barrett Browning had written to her sisters ‘I understand that she and Miss Hays have made vows of celibacy and of eternal attachment to each other – they live together, dress alike …it is a female marriage’. A photograph of the two women certainly shows them dressed alike, skirts topped by tailored shirts and jackets. Matilda, who preferred to be known as ‘Max’, is lean and saturnine. She was a novelist, who in 1847 had, with Emilie Venturi’s elder sister, Eliza Ashurst, embarked on the daring project of translating the works of George Sand. When she and Charlotte arrived in Rome they were looking for freedom from the social constraints imposed in America and England. Charlotte wrote that in Rome ‘the Mrs Grundies [are] so scarce, [and] the artist society ..so nice, that it is hard to choose or find any other place so attractive’. They spent most of the next five years or so in Rome – during the winter and spring of 1856 to 1857 Anna Jameson was part of their circle. But the Hays/Cushman female marriage was volatile and in 1857 came to a violent end – swearing certainly and, fisticuffs, possibly, were involved – and Matilda was forced to leave Rome.

Nine years later she published a novel, Adrienne Hope, in which she painted a very lifelike picture of Roman life as experienced by the expatriate English. Her main protagonists live in what was clearly the apartment in the via Gregoriana, along from the top of the Spanish Steps, in which she had lived with Charlotte: ‘a suite of rooms on the fourth piano, beneath the windows of which Rome lay extended like a panorama… There lies the Queen City of the World, with its quaint, irregular, grey roofs, its 364 churches, its noble pagan temples and imperial palaces, noble in their ruin and decay, basking through the day in the undimmed lustre of an Italian sun, to be glorified by its setting rays of gold, and crimson, and purple, the depth and richness of whose hues none who have not seen can by any means imagine, and none who have seen can ever forget.’ [For more about Matilda Hays and Adrienne Hope see here.]

Although Rome was at this time the centre for artistic training there was from the mid-19th century a revived interest in medieval Italy as inspiration for both art and literature. Tuscany in general and Florence in particular was the mecca for English devotees. One such arrival was Louise de la Ramée, who wrote under the pen name Ouida. She had already had considerable success and had made a considerable amount of money from her sensational novels. Having found her life in Bury St Edmunds insufficiently exciting she left England for Florence, where she quickly fell in love with a neighbour, the Marchese della Stuffa, for whom she felt all the passion that she had previously only been able to allow to her heroines. However, what she didn’t for a long time realise was that the Marchese was already spoken for – he had for several years been the ‘cavalier servante’ of Mrs Janet Ross – queen bee of the English circle in Florence. As her biographer put it. ‘Soon there was open enmity between Ouida and Mrs Ross, each fiercely resenting what she considered the other’s preposterous tendency to behave as if della Stufa were her property. Both were women of strong character, Mrs Ross the more domineering, Ouida the more impassioned’.

Ouida took up what she considered was her best weapon – her pen -and wrote a roman a clef based on this intriguing triangle – entitling it with the mot just – ‘Friendship’. When one knows something of the background, it makes a very good read. She describes Mrs Ross in the character of Lady Joan as ‘ a faggot of contradictions; extraordinarily ignorant, but naturally intelligent; audacious yet timid; a bully, but a coward; full of hot passions, but with cold fits of prudence.. She had a bright, firm, imposing way of declaring her opinions infallible that went far towards making others believe them so .’ Her own character was quite the reverse – all modesty and balm, ‘She gave him a yellow rose from a cluster that she had been placing in water as he had entered; there was tea standing near her on a little Japanese stand; she poured him out a cup, and brought it to him by the hearth; he followed all her movements with a sense of content and peace. As she tendered him the little cup, his fingers caressed hers, and as he drew the cup away, his lips lingered on her wrist. She coloured and left him.’

Her friends begged her not to publish it – the Ross side threatened a libel suit. Eight years later a reviewer wrote: ‘Italy was destined to do more for Ouida, as an artist, in a larger sense of the word, than to satisfy her ideal of the beautiful in landscape. An experience was reserved for her there, or more probably, a series of experiences, which vastly enlarged her knowledge of living men and women’.

Janet Ross was a member of a family of strong-minded women. In 1888 she and her husband bought a castle near Settignagno. In her memoirs she recounts her investigation of its history and its reclamation, describing for instance ‘having hateful French wallpaper scraped off the walls and having them washed a light grey stone colour – to the dismay of the workmen’ – so like all the villas in Tuscany idylls, where the jarring contemporary is erased in order to reclaim the peace of the past. Forging the path that so many later have followed she wrote a cookery book, Leaves from our Tuscan Kitchen. Those intimate with the Ross household later made clear that, of course Mrs Ross never needed to concern herself with the workings of the kitchen – and her cook, who prided himself on being able to produce more than the cookery of the region, had provided her with recipes that were, as a result, by no means authentically Tuscan. The commission for the book had, in the first instance, come from J.M. Dent to Janet Ross’s young niece, Lina, who, however, thought a cookery book dull work and preferred another commission, The Story Of Assissi. For the same ‘Medieval Towns’ series Janet Ross wrote The Story of Pisa and Lina’s friend, Margaret Symonds, The Story of Perugia.

Lina married an artist, Aubrey Waterfield, and in 1905 they bought their own castle, Fortezza della Brunella, near Carrara. Three years later Lina wrote Home Life in Italy, describing, in her turn, how they had made their castle habitable, and writing about their servants and local customs. The castle sounds magical: ‘As the evening draws in, wisps of clouds become suffused with a lustre of rose-purple and gold, to fade with the light to the colour of a Florentine iris. How often have I not returned home dazed by it all, and reached the drawbridge just as the birds were settling to rest with a great flutter and commotion among the ilexes in the moat..’ In 1917 she was one of the founders of the British Institute at Florence, which has subsequently served as an easy escape route into Italy for England’s well-heeled youth. From 1921 until 1939 Lina Waterfield was Italian correspondent for the Observer, speaking out firmly against Mussolini. That life at Fortezza della Brunella was for a child the embodiment of arcadia is set out in the memoir, A Tuscan Childhood, written by Lina’s daughter, Kinta Beevor, and published in the 1980s. Thus three English women of one family have between them recorded 100 years of Tuscan life.

At the same time as the Waterfields were restoring their castle, another English woman, Georgina Graham was living near Carrara, enjoying life in Italy and writing of it In a Tuscan Garden. Rather than a horticultural treatise this was in essence a guide for those wishing to move to Italy. ‘The ideal condition of residence is to have the home in England, and to be able to leave it for the winter or spring months… But when that ideal is beyond attainment, and when one has to choose a place of exile, Italy appears to me, taking it all round, to afford greater compensations than any other country.. Before settling in Tuscany, I had heard the remark that English society in Florence was for the most part so unpleasant, that every one did his best to keep out of it, and that if you wished to make a mortal enemy, you had only to offer to introduce one person to another.’. Doubtless the standoff between Mrs Ross and Ouida had many lesser emulators.

Mrs Graham continues, evoking the Florence of A Room with a View: ‘Nowadays Florence may be said to be one vast pension, it was totally different when I first knew it in the sixties; such places hardly existed then, and if they had, the class of English visitors of that day would not have gone into them. Many of them were badly off –; but it would not have occurred to them to herd with other people.’ Describing how easy it is to rent rooms for the long term, she comments: ‘It is astonishing how many Englishwomen of small means there are living here in respectability, and comfort in their own small etage, who, if in London, would be in comfortless suburban lodgings, in two rooms in one of those “ladies’ flats” to which all sorts of drawbacks and restrictions are attached. In Florence everything lends itself to their independence.’ Georgina Graham relates that she was seized with ‘Italy Fever’ back in the 1860s but that as time has passed ‘a long residence in Italy gives an intimate knowledge of her people, her standards, and her morale generally, under the influence of which the poetry becomes less prominent, and what may be called the seamy side is apt to be painfully to the front. But in spite of all, to those who have once yielded to its charm, it ever remains the enchanted land.’

This ‘Italy Fever’ had doubtless seized many of the women who were not so fortunate as Mrs Graham in finding themselves enjoying a large Tuscan villa and garden but, as she describes, happily occupied a room or two in Florence, with or without a view. I have been struck by the number of books that were published about Tuscany by women writers at the turn of the 20th century, including a couple by a woman of whom I had never before heard. One was Scenes and Shrines, written by Dorothy Nevile Lees, who had been born in Wolverhampton to a reasonably prosperous family. In 1903, aged 23, gripped by Italian fever, inspired by the poetry of Byron and Shelley, she left Wolverhampton and travelled alone to Florence. At the opening of Scenes and Shrines she recounts how ‘ I passed the great mountain gates which bar the way to Italy, the enchanted land of my childish imaginings, the Mecca of my dreams.’ In order to learn Italian as quickly as possible she chose to board with a middle-class Florentine family and plunged with a will into Italian life.

Both Scenes and Shrines and a second book, Tuscan Feasts and Tuscan Friends, were published in the same year, 1907, and were probably the result of collecting together articles that she had already had published in the English press. Tuscan Feasts opens with a hymn to her new land ‘ O Italy, my land of Heart’s Desire/No Paradise could be more fair than thou’, and the finding of her dream villa. ‘The Villa strictly speaking, was not beautiful; its time-stained plastered walls, its lofty height, its heavily-barred windows were a little gaunt and forbidding; and yet, as I stepped down from the carriage, I felt instinctively that I had found the place of dreams and peace’. If Dorothy Nevile Lees had been of our time she would have been a participant in ‘A Place in the Sun’ – making a television programme about her new Tuscan life.

I then discovered that in 1907 Dorothy Nevile Lees met Edward Gordon Craig, theatrical director, stage designer, son of Ellen Terry, married man and father, and, clearly, a great charmer, and that from 1908 until it folded in 1929 she was the editorial mainstay of his theatrical magazine, The Mask. She lived all this time in Florence – while Craig travelled the world – he went through a couple of marriages, and several affairs – including one with Isadora Duncan (by whom he had two children). In 1917 Dorothy herself had a son, David, by him, the existence of whom Craig was very keen to keep quiet – so quiet indeed that his entry in the new ODNB makes no mention whatsoever of Dorothy Nevile Lees or her son (although conceding that Craig had many children). It is clear Craig did what he could to ensure that David Lees, who in fact became an internationally-renowned photographer, would become another of England’s children lost in Italy. In 1935 Dorothy heard that Craig had denied that he was David’s father. When she commented on this, by way of reply he counselled her ‘not to blab’.

Dorothy Nevile Lees, clearly a woman of independent spirit, remained in Florence during the Second World War, shielding Craig’s archive from the Nazis, despite an office raid, and eventually giving the British Institute in Florence a collection of his theatrical material. One cannot know what she had really expected when she arrived as she had put it, in ‘the Mecca of my dreams’, but she had certainly carved out for herself an interesting life, one unlikely to have been her fate in Wolverhampton. [For more about Dorothy Lees see here.]

Life in a Tuscan villa in the years before the Second World War and then in wartime Florence falls to the lot of Fenny, the creation of Lettice Cooper, whose eponymous novel, Fenny, was published in 1953. I don’t know enough of Lettice Cooper to know what part Italy played in her life, but the loving description of her heroine’s enjoyment of her surroundings at least suggest that the author relished her research. Fenny is not the chatelaine of the villa – that character is a spoilt and wilful Englishwoman – but Ellen Fenwick, who until shortly before the opening of the novel, which begins in 1933, is a teacher in an English girls’ high school and is then invited to Tuscany as a governess. One can imagine her background as not unlike that of Dorothy Nevile Lees. When she arrived at the villa Fenny considered life within its grounds as paradise –she really does say ‘When I first arrived her I thought I’d got into a house in a fairy-tale’ – a very suitable romance follows but it is stifled by the lady of the house – Fenny later copes with the war – and ensures that her much loved pupil will not suffer as she suffered. A conventional enough plot, lovingly told against the backdrop of Italian life and landscape. The novel ends with Fenny saying to the young boy she has rescued from the disasters of war, ‘All right, Dino! We’ll go to Rome.’

Life in a Tuscan villa in the years before the Second World War and then in wartime Florence falls to the lot of Fenny, the creation of Lettice Cooper, whose eponymous novel, Fenny, was published in 1953. I don’t know enough of Lettice Cooper to know what part Italy played in her life, but the loving description of her heroine’s enjoyment of her surroundings at least suggest that the author relished her research. Fenny is not the chatelaine of the villa – that character is a spoilt and wilful Englishwoman – but Ellen Fenwick, who until shortly before the opening of the novel, which begins in 1933, is a teacher in an English girls’ high school and is then invited to Tuscany as a governess. One can imagine her background as not unlike that of Dorothy Nevile Lees. When she arrived at the villa Fenny considered life within its grounds as paradise –she really does say ‘When I first arrived her I thought I’d got into a house in a fairy-tale’ – a very suitable romance follows but it is stifled by the lady of the house – Fenny later copes with the war – and ensures that her much loved pupil will not suffer as she suffered. A conventional enough plot, lovingly told against the backdrop of Italian life and landscape. The novel ends with Fenny saying to the young boy she has rescued from the disasters of war, ‘All right, Dino! We’ll go to Rome.’

And it was to Rome in the year of Fenny’s publication that the novelist Elizabeth Bowen went, sponsored by the British Council. She had made many previous visits, but her husband had recently died and she made this extended stay the occasion of specific research for her book, A Time in Rome. I love this book. I love the way she explains how she got to grips with the city –‘My object was to walk it into my head and (this time) keep it there.’ I love the way she is alone as she does this (or at least appears to be alone) – I like the idea of the solitary walker –the observer. And I love this sentence she wrote early on in the book; ‘To talk of “entering” the past is nonsense, but one can be entered by it, to a degree.’ The book’s final sentences even on re-reading are still affecting. ‘Only from the train as it moved out did I look at Rome. Backs of houses I had not ever seen before wavered into mists, stinging my eyes. My darling, my darling, my darling. Here we have no abiding city.’

Through the second half of the 20th and into the 21st century women have still relished the challenge of reshaping a life in Italy. And as in the 18th and 19th centuries, writing still offers the possibility of earning a living and a new and interesting locality provides possible material for the writing. Detective fiction, blending social observation and deduction/intuition, has proved a successful genre for women writers; an exotic locality gilds the lily. The best-known woman writer of English-language Italian detective fiction is Donna Leon, whose policeman, Guido Brunetti, is the epitome of Venetian suavity and good humour. However Donna Leon, although an intriguing woman, is an American and doesn’t qualify for discussion today.

But while thinking of women writers and detection in Venice I must mention in passing Sarah Caudwell – the pen name of Sarah Cockburn –now, alas, dead – who led a life of bella libertà. She was a charming and scatty, pipe-smoking lawyer who wrote four witty detective novels, the first, Thus Was Adonis Murdered, set in Venice. While I am sure Sarah enjoyed complete freedom at all times and didn’t need to go to Venice to find it, it was assumed by those who knew her that an opportunity to foster close acquaintance with young Venetian men made her research all the sweeter.

Magdalen Nabb, an English writer of detective fiction, has, like Donna Leon, created an Italian policeman. Her central character is Marshal Guarnaccia and she has posted him in Florence, close to the Pitti Palace. All I know of Magdalen Nabb is what is revealed on her book jackets – but in its bare outline it is the epitome of the ideal life of the English women writer in Italy. ‘She was born in Lancashire in 1947 and trained as a potter. In 1975 she abandoned pottery, sold her home and her car, and went to Florence with her son, knowing nobody and speaking no Italian’. When she wrote the first of what are now 12 books in her detective series she was living in an apartment in Casa Guidi. Indeed I first came across her novels while staying there myself, in the Brownings’ drawing room, in the Library supplied by the Landmark Trust.

Another English writer, who has written at least one thriller with an Italian setting, and who has also taken root in Florence, is Sarah Dunant. She has described in an interview how, after the break up of a relationship, she thought life needed a radical change – and so bought a flat in Florence. She holds the city responsible for her own personal renaissance and it, naturally, became the setting for The Birth of Venus, a novel that I am sure is selling very well and ensuring her a comfortable Florentine life. [The Birth of Venus was the only one of Sarah Dunant’s Italian novels published when I gave the talk – but she has written more since – see here.]

Another English writer, who has written at least one thriller with an Italian setting, and who has also taken root in Florence, is Sarah Dunant. She has described in an interview how, after the break up of a relationship, she thought life needed a radical change – and so bought a flat in Florence. She holds the city responsible for her own personal renaissance and it, naturally, became the setting for The Birth of Venus, a novel that I am sure is selling very well and ensuring her a comfortable Florentine life. [The Birth of Venus was the only one of Sarah Dunant’s Italian novels published when I gave the talk – but she has written more since – see here.]

As well as being the setting for detective stories, which I could perhaps tie into my gothic theme, Italy has also provided the setting for a number of contemporary arcadian or fairyland novels. In these authors have gathered together a group of disparate characters and allowed enchantment of one kind or another to work on them. In Enchanted April, published in 1923, Elizabeth von Arnim describes in loving detail (detail so easily translated into a gentle film) how four women, previously unknown to each other, rent a castle on Italy’s Ligurian coast, overlooking the bay where Shelley drowned, and find themselves and happiness.

As well as being the setting for detective stories, which I could perhaps tie into my gothic theme, Italy has also provided the setting for a number of contemporary arcadian or fairyland novels. In these authors have gathered together a group of disparate characters and allowed enchantment of one kind or another to work on them. In Enchanted April, published in 1923, Elizabeth von Arnim describes in loving detail (detail so easily translated into a gentle film) how four women, previously unknown to each other, rent a castle on Italy’s Ligurian coast, overlooking the bay where Shelley drowned, and find themselves and happiness.

Amanda Craig’s Love in Idleness cleverly and amusingly reworks A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream in the setting of a houseparty in a Tuscan villa, effortlessly evoking the magic suspension of reality that overtakes her characters. ‘The heat intensified. At night the house creaked and whispered, so that they woke to confusion, climbing out of their dreams on the ladder of light cast by the shutters, excited, ashamed, frustrated. During the day each person became more and more enervated, yet also more relaxed.’

Amanda Craig’s Love in Idleness cleverly and amusingly reworks A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream in the setting of a houseparty in a Tuscan villa, effortlessly evoking the magic suspension of reality that overtakes her characters. ‘The heat intensified. At night the house creaked and whispered, so that they woke to confusion, climbing out of their dreams on the ladder of light cast by the shutters, excited, ashamed, frustrated. During the day each person became more and more enervated, yet also more relaxed.’

A similar atmosphere of shimmering heat and long shuttered siestas, interspersed with bursts of uncharacteristic behaviour, is what I remember of The Italian Lesson, a 1985 novel by Janice Elliott. Again a group, most previously unknown to each other, gathers for a holiday – this time in a restored castle a few miles outside Florence. William, one of the central characters, has for years been researching a monograph on E.M. Forster and Italy and the novel is intertwined with Forsterian allusions. His wife is recovering from a still birth and in the course of the novel another baby is carelessly lost to death, its fate an echo of the bronzed baby in Forster’s Where Angels Fear to Tread, and an echo of all those others that have been lost in Italy – in both fact and fiction.

A similar atmosphere of shimmering heat and long shuttered siestas, interspersed with bursts of uncharacteristic behaviour, is what I remember of The Italian Lesson, a 1985 novel by Janice Elliott. Again a group, most previously unknown to each other, gathers for a holiday – this time in a restored castle a few miles outside Florence. William, one of the central characters, has for years been researching a monograph on E.M. Forster and Italy and the novel is intertwined with Forsterian allusions. His wife is recovering from a still birth and in the course of the novel another baby is carelessly lost to death, its fate an echo of the bronzed baby in Forster’s Where Angels Fear to Tread, and an echo of all those others that have been lost in Italy – in both fact and fiction.

I shall end this talk in Venice, Mrs Radcliffe’s ‘fairy city’, with Julia Garnet, the creation of Salley Vickers, who will give the First Persephone Annual lecture on the 5th October, discussing Miss Garnet alongside Persephone’s Miss Pettigrew and Miss Ranskill. I am very fond of Miss Garnet, who is the epitome of all the women whom we have encountered today. One can, in fact, imagine that Julia Garnet is what Fenny would have become if she had not been transported to Tuscany in her youth. For Julia Garnet came to Venice only on her retirement from teaching and there found the angel that was to guide her to the next world. Like Elizabeth Bowen, she walks the city into her head, transformed by it – ‘Venice has changed me’ she thought. We can see that Julia Garnet, while remaining essentially herself, has changed – her emotions and understanding expanded, Venice and the people she found there, Anglo-American as well as Italians, having worked their magic. As in so many novels that centre on Venice the cast of characters includes art historians and art restorers and I will leave you with a glimpse of this –the handwritten diary of a young Englishwoman, which details a three-month stay in Venice, where she was taking an art history course [Note: this diary was an item that I had in my book dealing stock at the time]. This was in 1986 – exactly 200 years after Lady Elizabeth Forster wrote up her Italian diary. What this young woman puts on paper is equally self-regarding, sprawling and observant – it could be raw material for a novel – a romance, a romantic comedy, a detective novel, or even, perhaps, a tragedy. The writer is anonymous –– although I suppose there are sufficient clues scattered throughout that would enable her identity to be discovered. But let her remain anonymous, her experience in Italy in the mid 1980s merely a contemporary version – factor in drugs, sex and rock and roll – of the bella libertà enjoyed by all our English women writing in Italy – her refrain, like that of all the others, is: ‘I never want to go back to England.’

Copyright

Amanda Craig, Anna jameson, claire clairmont, dorothy NEvile Lees, Elizabeth Barratt Browning, Elizabeth Bowen, Emilie Venturi, Georgina Graham, Janet Ross, Janice Elliott, Jessie Mario White, Lady Elizabeth Forster, Lettice Cooper, Lina Waterfield, Magdalen Nabb, Mariana Starke, Mary Shelley, matilda hays, Mrs Radcliffe, Ouida, Persephone Books, Sarah Caudwell, Sarah Dunant

Women Writers And Italy: Stalking Matilda Hays And ‘Adrienne Hope’

Posted by womanandhersphere in Women Writers and Italy on February 3, 2014

A brief visit to Rome last week – staying once again in the abidingly diverting Landmark Trust apartment at the side of the Spanish Steps – allowed me to retrace yet again the footsteps of some of the mid-19th-century women expatriates – British and American – who for a number of years made the city their home.

In the mid-1850s the intriguing Matilda Hays, journalist and novelist, was living in Rome – with her long-term partner, Charlotte Cushman, the American actress, who had now retired from the stage. For at least some of the time they lived, enjoying what Elizabeth Barrett Browning termed a ‘female marriage’, at 38 via Gregoriana, a road leading off to the right at the top of the Spanish Steps – as seen in the view above.

As the women walked down from their home – perhaps to have tea at the Caffe Inglese in the Piazza di Spagna – they presumably sometimes thought of John Keats, who had died in a room on their left (as seen in the above photo), on the floor with the terrace, just 30 years or so earlier. We were staying in the floor above.

Matilda Hays describes something of the life of her friends and acquaintances in her novel, Adrienne Hope, the story of a life, published by Newby in 1866. What the novel may lack in plot it makes up for in its ‘factional’ interest to those, like me, who are keen to repopulate the forestieri quarter of Rome with its mid-19th-century inhabitants. I must confess I know far more about their funny little ways than I do those of any Roman, ancient or modern.

So it interested me that Matilda Hays gives her leading characters, Lord Charles and Lady Charlotte Luttrell, ‘a suite of rooms in a large house at the southern end of the Via Gregoriana, rooms on the fourth piano [floor], beneath the windows of which Rome lay extended like a panorama, the turbid Tiber separating the Janiculum from its sister hills, and gliding like a monster sea-snake through the valley from its entrance into the city close to the Porta del Popolo to its exit south below the Aventino. There lies the Queen City of the World, with its quaint, irregular, grey roofs, its 364 churches, its noble pagan temples and imperial palaces, noble in their ruin and decay, asking through the day in the undimmed lustre of an Italian sun, to be glorified by its setting rays of gold, and crimson, and purple, the depth and richness of whose hues none who have not seen can by any means imagine, and none how have seen can ever forget.’

There has, of course, been much building – and rebuilding – in the course of the past 150 years and even from the topmost floor of a house at the southern end of the via Gregoriana I doubt that such a view could now be obtained – although that from the Piazza Trinita dei Monte, into which the street debouches, is still one of the most magnificent in Rome. Via Gregoriana has probably been renumbered since Hays lived there; but, for the record, number 38 is now towards the northern end, facing across over the city. Alas, I could not test whether or not the Tiber could be seen from the fourth piano.

The novel contains much visiting of artists’ studios in Rome. The comment is made that ‘Among all the different races of living sculptors Americans alone have shown a tendency to produce something new and original, and though none have been eminently successful – choosing for and the most part the wild Indian life of the North American continent for their subjects – yet this departure from the stereotyped classic form is welcome and refreshing..’ Alas, although it would have been neat, this observation probably comes too early to refer to the work of Edmonia Lewis, a young woman of African-American and Native-American parentage, who, from 1865, made her home in Rome, sculpting, among many other works, Hiawatha and his daughter (1868).

Matilda Hays was commenting on the pagan sculpture that was very much the mode of the moment and was well acquainted with the English sculptor, John Gibson, who was leading the vanguard. In the novel, Sir Charles and Lady Charlotte visit Gibson’s studio in via Fontanella – close to the Piazza di Spagna.

‘The transition from the dirty unfragrant street to the cool large studio, filled with lovely statues and bassi rilievi, with a green vista of moss and fern and trickling water beyond, and a scent of the rich flowers of the south wafted on the breeze, was a pleasant surprise both to eyes and nose. The mellow sunlight poured down upon the verdant niche in the small garden – which constantly falling water of a fountain keeps cool and fresh through the burning heats of summer, – and streamed in at the open door, throwing a beautiful light upon the graceful limbs of ‘Hylas and the Water Nymphs’, ‘Psyche and the Zephyrs’, two of the fairest groups the cultivated meditative brain has created, and the cunning hand of the master has wrought.’

‘Hylas Surprised by the Naides’ is now in Tate Britain – click here for details – having been given to the nation in 1847. That sculpture had, therefore, left Gibson’s studio long before Matilda Hays knew him – she had presumably seen the work when it was publicly displayed or perhaps he did have a cast of it to be admired by studio visitors.

Once inside Gibson’s studio Lady Charlotte Luttrell is shown his most infamous work – a statue of Venus, her skin tinted. Through her character Matilda Hays voices the popular controversy that surrounded the work – Lady Charlotte shows herself, politely, to be ambivalent about this use of colour on statuary.

Lady Charlotte is then taken to an upstairs studio to meet Gibson’s star pupil, the young American, Harriet Hosmer.

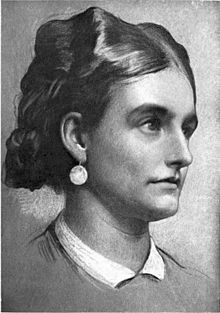

Bearing in mind that in the mid-1850s Matilda Hays had for a time left Charlotte Cushman for Harriet Hosmer, this is how she is described in Adrienne Hope:

’..there was something very winning in the fair, broad brow, with its clustering sunny brown curls, the inevitable velvet cap crowning them; the deep, earnest eyes, the compact nose, firm-set mouth, and square chin and jaw; the trim little figure, with its clothing of grey skirt and holland blouse, and as she addressed her visitors, the quaint short phrases, the peculiar sharp-cut of the words reminding them of her master (snap and bite, the wags called master and pupil) and the eyes and face danced and glowed with fun and fire. Lady Charles thought her as charming a sprite as the Puck she had modelled – and for which, before her visitors left, she received an order, accompanied by such kind expressions of admiration and good-will that the value of the order to the young artist must have been considerably enhanced.’

Gibson’s studio was at 4 via Fontanella – all trace of it, I am sure, long swept away. Via Fontanella is a continuation, across the via del Babuino, of via Margutta where Harriet Hosmer went on to have her own studios. The two addresses I know for her, at numbers 5 and 116 are, if the numbering is anything like it was in the mid-19th century, both at the via Fontanella end of the long via Margutta.

The other characters in Adrienne Hope include a Miss Reay, a literary woman, who has seen a good deal of the world and is not very much in love with it. She was ‘engaged in editing a philanthropic journal, with which a great deal of practical work is connected, the chief burden of which falls upon myself and two or three others..’ ‘I made a fair start in early life in a literary career.. but cruel circumstances intervened..the best years of my life were utterly and uselessly sacrificed..’

Poor put-upon Miss Reay is, of course, Matilda Hays herself. She had been a co-founder of The English Woman’s Journal – Britain’s first feminist monthly magazine – and had for a time been its editor before falling out (‘cruel circumstances’) with her fellow workers, Barbara Bodichon and Bessie Rayner Parkes. Miss Reay was a solitary, intrepid woman: ‘ I confess that to this day, habitually as I have walked and travelled alone, I have never experienced the smallest annoyance, and I should not hesitate to set out alone tomorrow, for travels as protracted and solitary as those of Madame Ida Pfeiffer..’ [Ida Pfeiffer being one of the first woman explorers.]

Also making an appearance in Adrienne Hope is a Lady Morton, the widow of a peer, who probably bore a very close resemblance to the slightly mysterious Theodosia, Lady Monson, a benefactor of The English Woman’s Journal, with whom Hays later lived.

Matilda Hays left Rome on 20 April 1857 – two days after a violent row with Charlotte Cushman – a final break that, after a few years’ gestation, resulted in Adrienne Hope. She died 40 years later at 15 Sefton Drive, Toxteth Park, Liverpool and (thanks to Phil Williams for the information) is buried in Toxteth Cemetery where, I believe, her headstone can still be seen.

adrienne hope, charlotte cushman, John Gibson, matilda hays, via fontanella, via margutta

Recent Posts

- Suffrage Stories: The Mystery of Nurse Pine’s Medal – Solved

- Mariana Starke and the Demon Duke: your opinion requested

- The Garretts And Their Circle: A Talk For International Women’s Day

- Books and Ephemera By and About Women: Catalogue 211

- Mariana Starke: ‘A Tissue of Coincidences’: Lady Mary De Crespigny And Hortense De Crespigny

Archives

- Join 2,787 other subscribers

All My Books

- Art and Suffrage: a biographical dictionary of suffrage artists

- Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye's Suffrage Diary

- Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle

- Kate Parry Frye: the long life of an Edwardian actress and suffragette – ebook available on iTunes

- Kate Parry Frye: the long life of an Edwardian actress and suffragette – ebook available on Amazon

- Millicent Garrett Fawcett: Selected Writings, co-edited with Melissa Terras

- The Women's Suffrage Movement: a reference guide

- The Women's Suffrage Movement: a regional survey

Articles

- 'Hunger Striking for the Vote'

- 'Women do not count, neither shall they be counted': Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the 1911 Census (co-authored with Jill Liddington). History Workshop Journal

- BBC History: Women: From Abolition to the Vote

- Emily Wilding Davison: Centennial Celebrations. Women's History Review

- Introduction to 'Bewildering Cares' by Winifred Peck

- Introduction to six novels by Elizabeth Fair

- Introduction to three novels by Rachel Ferguson

- Police, Prisons and Prisoners: the view from the Home Office. Women's History Review

- The Bloomsbury Project: A Woman Professional in Bloomsbury: Fanny Wilkinson, Landscape Gardener

Audio/Audio Visual

- 'Collecting The Suffragettes': A Fully-Illustrated Video Talk

- 'Collecting The Suffragettes': A Fully-Illustrated Video Talk

- 'Furrowed Middle-Brow Fiction'

- 'Suffragette': the making of the film. Q & A discussion hosted by the Women's Library@LSE

- BBC Radio 3: Kitty Marion: Singer, Suffragette, Firestarter

- BBC Radio 4 1913: The Year Before: The Women's Rebellion

- BBC Radio 4 Deeds Not Words: Emily Wilding Davison

- BBC Radio 4 Woman's Hour: The Garrett Andersons: Pioneering Mother And Daughter

- BBC Radio 4 Woman's Hour: Who Won the Vote for Women – the Suffragists or the Suffragettes?

- BBC Radio 4: Archive on Four: The Lost World of the Suffragettes

- BBC Radio 4: Great Lives: Millicent Fawcett

- BBC Radio 4: Millicent Fawcett, Votes for Women and British Liberalism

- BBC Radio 4: Things We Forgot To Remember: Suffragettes

- BBC Radio 4: Votes For Victorian Women

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour Suffragette Mary Richardson Who Slashed the Rokeby Venus

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour Suffragette Special 26 July 2013

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour: Emily Wilding Davison and the 1911 census boycott

- BBC Radio 4: Woman's Hour: Suffragettes and Tea Rooms (starts c 27 min in)

- BBC Two 'Ascent of Women'

- BBC World Service Lost World of the Suffragettes

- Channel 4 TV: Clare Balding's Secrets of a Suffragette

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Millicent Fawcett

- Endless Endeavours: from the 1866 women's suffrage petition to the Fawcett Society: The Women's Library@LSE Podcast

- Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle.

- Fanny Wilkinson: A Talk

- ITV: The Great War The People's Story Episode 2 (including Kate Parry Frye and her diary)

- No Vote No Census. National Archives talk on the suffragette boycott of the 1911 census

- Parliamentary Radio: Interview in the House of Commons about Emily Davison on 4 June 2013

- The Royal Society of Medicine: Talk on 'Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her Hospital'

- UK Parliament Videoed Talk 'Vanishing for the Vote', together with Dr Jill Liddington and Prof Pat Thane

- UK Parliament: Videoed talk in the House of Commons: Campaigning for the Vote: from MP's Daughter to Suffrage Organiser – the diary of Kate Parry Frye

Guest Blogs

- British Library Untold Lives: Emily Wilding Davison: Perpetuating the Memory

- Feminist & Women's Studies Association Blog: Kate Frye: A Feminist Foot Soldier

- History of Government Blog: No 10 Guest Historian Series: We Wanted To Wake Him Up: Lloyd George And Suffragette Militancy

- History Workshop Online: Campaigning for The Vote: Kate Parry Frye's Suffrage Diary

- OUP Blog: Why Is Emily Wilding Davison Remembered As The First Suffragette Martyr?

View Books for Sale