Posts Tagged women’s suffrage

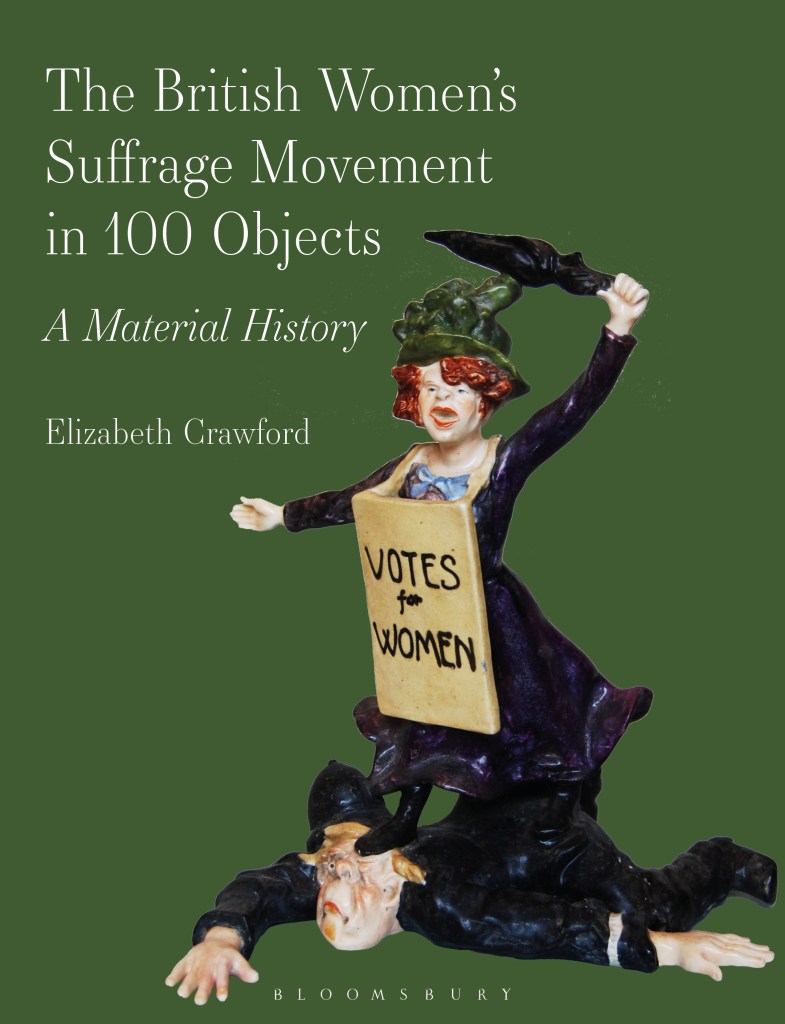

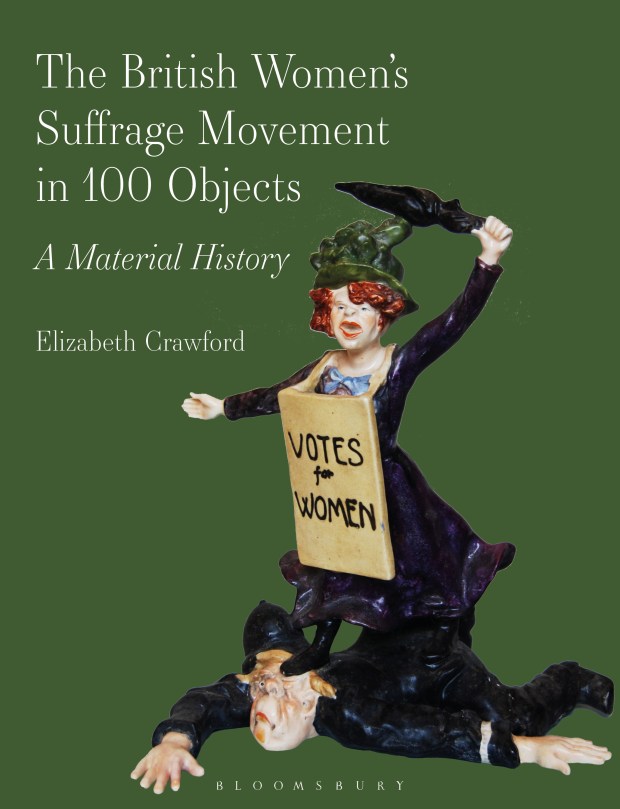

The British Women’s Suffrage Movement in 100 Objects: a material history – FORTHCOMING IN JULY

Posted by womanandhersphere in British Women's Suffrage Campaign in 100 Objects on February 9, 2026

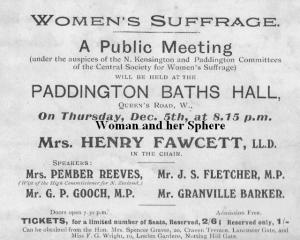

I had no thought of producing another book when, one day in October 2023, I opened up my laptop, ready to watch an online auction mounted by Bonhams. This Votes for Women sale was devoted to suffrage memorabilia from the collection put together by a couple I’ve known ever since I began dealing in books and ephemera in the mid-1980s. I had no intention of bidding for anything in the auction as by 2023 the prices reached for suffrage material at such auctions had soared into the stratosphere. But, naturally, I took a professional interest in seeing what was up for sale – and the prices they would achieve. And I had a personal interest in that some of the items were ones I had myself sold to the vendors many years ago.

Watching the bidding was absorbing, but as the sale progressed I realised I was experiencing a niggling conflict between what might be termed my instinct as a trader and my instinct as an historian. Bonhams had organised the lots in the sale in a way as to appeal to bidders, grouping together items of a similar type, such as textile rosettes or china or badges or books – but this arrangement by no means coincided with what I knew to be the dates of their production. In my mind I was itching to reorder the lots into an historically coherent order. Well, there lay the germ of an idea …and it slowly gained traction..and, in due course, a publishing contract with Bloomsbury Academic. The result of my labours will be published in July.

For the book tells the story of the British ‘votes for women’ campaign in a sequence of 100 objects. From the beginning of the campaign in 1866 until all women were granted the vote on the same terms as men in 1928, women used every means in their power to persuade the government to allow them the right to elect members of parliament. Through the analysis of an astonishing array of objects – including books, bags, petitions, posters, plays, photographs, china, leaflets, newspapers, games, jewellery, sashes, films, and figurines – all of which are illustrated – The British Women’s Suffrage Movement in 100 Objects explores the role that material culture played in this vital struggle. Each of the 100 objects is illustrated, the accompanying text setting it in its context to explain the campaign’s politics and the part played by key personalities.

I must say that when I began work on the book it had not occurred to me that the suggestion could be voiced in any western democracy that women should be relieved of the right to the vote. But, that day having come, although not yet here, there is all the more reason for understanding why and how British women won that right.

The book will be published in July in paperback at £24.99. To discover more details – as set out on the Bloomsbury website – including a special pre-order price and some most heart-warming reviews from readers who have viewed the text of the book in advance – see here.

My cup overflows – in that Bloomsbury will only accommodate six endorsements on their webpage – and nine readers were kind enough to give feedback on the book. I, as blushingly as self-promotion permits, set out below the final three to arrive. As you may imagine, I am immensely heartened – and hopeful that the 100 Objects will give a new clarity to the chronology, politics and personalities of the women’s suffrage campaign.

‘Drawing on a lifetime of groundbreaking scholarship on the British Suffrage movement and its materiality, Crawford’s new book is an essential read for anyone interested in the history of women’s campaigns for the vote. The British Women’s Suffrage Movement in 100 Objects brings to life in unprecedented detail the material world in which campaigners strove for social and political change, conveying this to new audiences with a lightness of erudition and a treasure trove of vivid detail. The extraordinary creativity and complexity of women’s activism during this era is made tangible through Crawford’s expert guidance.’ Dr Zoë Thomas, Associate Professor of Modern History, University of Birmingham

‘Beautifully illustrated and exceptionally curated, Crawford’s The British Women’s Suffrage Movement in 100 Objects is an essential and defining resource for the ways technological advances, community building, and popular culture played in the British campaign for “Votes for Women.” In clearly written and focused essays on everything from the intersection of the automobile and women’s rights to the ubiquity of comic suffragette ceramics, Crawford’s book will be of interest to scholars and general public alike.’ Heidi Herr Librarian for English, Philosophy, The Writing Seminars, & Student Engagement for Special Collections The Johns Hopkins University

‘The British Women’s Suffrage Movement in 100 Objects powerfully demonstrates the richness that material culture brings to the study of women’s histories. By centring objects, it reveals the political struggle as something lived, worn, exchanged, and displayed, rather than simply written or spoken. Together, the 100 objects offer an engaging, vivid and very human perspective on the suffrage movement, recovering voices and experiences that often remain muted in conventional narratives.’ Dr Miranda Garrett

Another Blue Plaque for Enterprising Women: Rhoda and Agnes Garrett Commemorated

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on March 11, 2025

I am delighted to report that two more of my ‘Enterprising Women’ have just been recognised with an English Heritage Blue Plaque. For the work of Rhoda and Agnes Garrett is now highlighted, this new plaque joining that of their sister/cousin, Millicent Fawcett, on the outside of their home and business premises, 2 Gower Street, Bloomsbury.

The first published study of their work is detailed in a section headed ‘The Home’ in my Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle (2002). Having continued the research in the intervening years, most recent discoveries were revealed in an online talk I gave last month for the Victorian Society. If you are interested it is, I believe, possible to buy a recording.

Thus, Rhoda and Agnes Garrett are now memorialized by two blue plaques, the other being by the gate to their Rustington, Sussex, house, then known as ‘The Firs’. I had the pleasure of unveiling that one in 2018.

And while Blue Plaques are on my mind, I’ll mention that Fanny Wilkinson, entirely forgotten before I made her the subject of the section ‘The Land’ in Enterprising Women, is also now memorialised by two. One is the English Heritage version, on her one-time flat in Bloomsbury

The other is in the garden of her former family home, Middlethorpe Hall, now a delightful hotel. I had the pleasure of giving a talk about Fanny and her work to accompany that unveiling in 2022.

I may say that I initiated none of these commemorations – I just didn’t think to do so – but how delighted I am that the work of these interesting women has touched the imagination of those who launched the four proposals.

And here’s the book that started it all:

330 pages, 75 illustrations £25 +pp (can be ordered directly from me – elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com).

Collecting Suffrage: Fake Flags – Or Why Researching Material Culture Matters

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on June 19, 2023

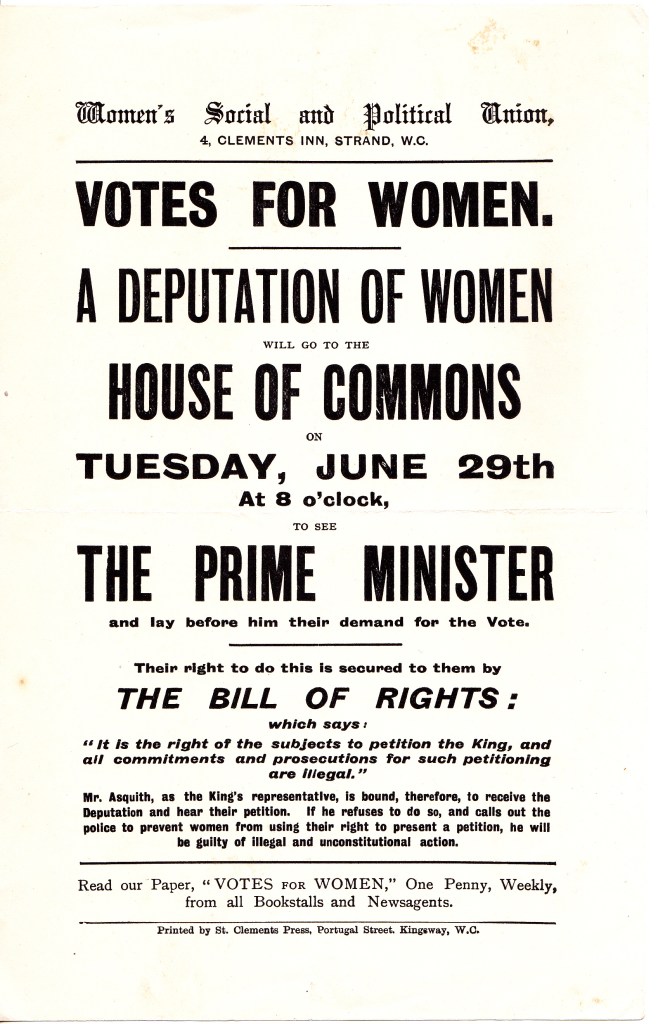

Led by Miss Kerr, who is carrying a WSPU flag, suffragettes parade outside the WSPU offices in Clement’s Inn (image courtesy of Women’s Library@LSE)

When I started in business nearly 40 years ago as a dealer in books and ephemera, specialising in the lives of women, there was little need to think twice about the authenticity of any appealing object. I do remember being very careful to check that a signature on, say, a photograph of Mrs Pankhurst was penned rather than printed but, in those days, ‘women’ as a class had not attracted the attention of scammers. How times have changed. And that change is particularly manifest in objects associated with the suffragette movement.

Nowadays I take extreme care, perhaps bordering on paranoia, to check the authenticity and provenance of any object before I add it to stock. For unscrupulous dealers are now ridiculing the suffragette movement by creating and selling objects that claim to be associated with the WSPU. Perhaps, unsurprisingly, the NUWSS has not attracted this attention, scammers knowing where lies the popular appeal.

This trade disturbs me on several levels. I am upset to see those with no knowledge or interest in the suffrage movement traducing the historical record, I am upset to see buyers disappointed when, thinking they have acquired an original object, they discover they have not, and I am particularly worried when, as has happened, a public collection acquires a spurious suffrage artefact.

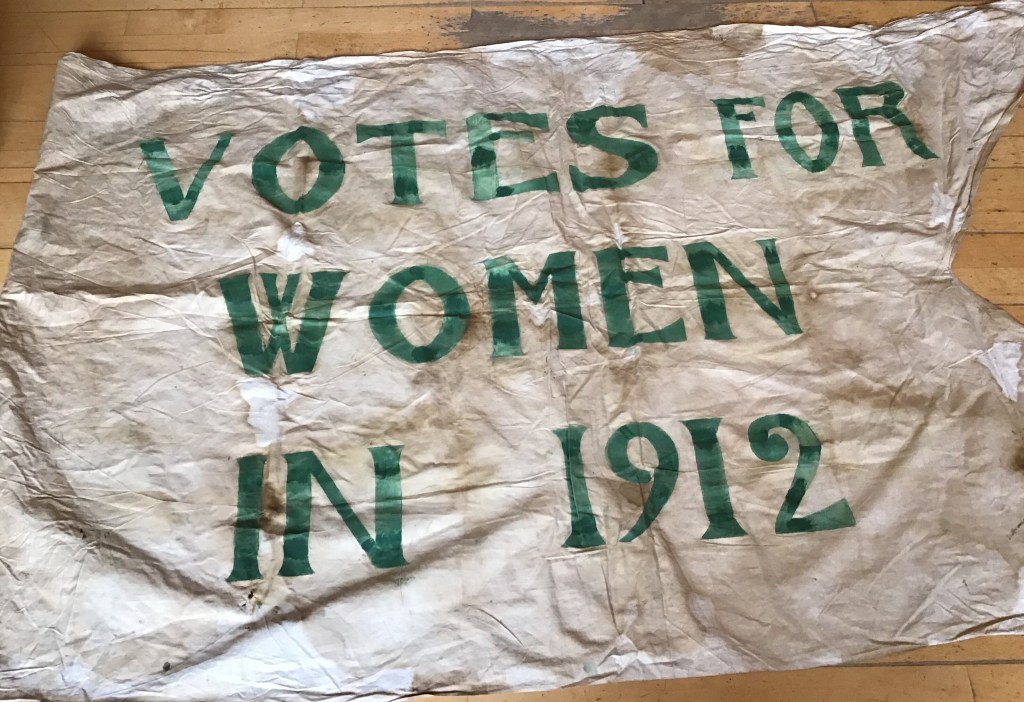

It may be useful to present the history of one element of suffragette material culture that currently concerns me: the phenomenon of the WSPU flag currently flooding the market.

It was probably three or four years ago that a purple, white, and green flag first appeared on an eBay site. Along the white side selvedge strip was printed the legend ‘WPSU 3 & 4 Clement’s Inn, Strand W.C.’. I have not kept a record of the price this object fetched, but it was, if memory serves, several hundred pounds. Another book dealer contacted the seller to point out that this flag was unlikely to be original, as the initials were incorrect – ie ‘WPSU’ rather than ‘WSPU’. He did not receive a reply, but answer was made in kind as another flag then appeared – with the middle two letters cut out – leaving only the ‘W’ and the ‘U’ – and the (correct) address. Laughable, really. In fact, at the moment (June 2023) one of these flags is available for sale on eBay – for £260 – although now the whole of ‘WPSU’ has been raggedly removed, leaving only the address.

Most of the flags now boast a ‘Votes for Women’ slogan across the central white stripe and have a variety of marks on the white webbing at the side. Currently (June 2023) there are 7 WSPU flags for sale on eBay: one is marked with ‘1912’, two with ‘London 1908’, one with ‘London 1910’, and two with ‘1910 WSPU’ (both of these listed by the same dealer). The flags are priced at between £149 and £895.

Between March and June 2023 27 ‘original’ WSPU flags were sold on eBay– their prices ranging from £58 to £310. Again, they are printed on the selvedge with dates and places – such as ‘Bath 1912’, ‘London 1914’ etc. They variously claim to have been found in ‘a box at an antiques fair’ or from ‘a deceased estate’.

A number of these flags have moved from eBay to terrestrial auctions and, on the whole, auctioneers do remove them from a sale once doubts are expressed as to their originality. I note that one auctioneer who initially refused to withdraw one of the flags from sale – and has since sold several more – does at least now note that their authenticity cannot be guaranteed. The flags have, of course, moved out of salerooms and are now to be found at antiques markets and fairs and I accept that, as they move further from their source, vendors may well not realise that they are selling fakes.

I have not inspected any of these flags in person – my reasons for knowing that they are not ‘right’ is based on my many years of archival research and on my hard-acquired knowledge of the trade in suffrage ephemera. At the most basic level, if you study the Flickr account of the Women’s Library@LSE, perhaps the most extensive photographic record of the suffrage movement available to view on the internet, you will note that there is no evidence of the WSPU flag as is currently being traded. At the head of this post is one of the few photographs to show a WSPU flag (we presume it is purple, white, and green but, of course, the photograph is in black and white). However, you will note that the orientation of the stripes is such that one of the colours (purple or green?) lies against the carrying pole, whereas on that of the fake flag all the colours meet the pole. That is to say, the stripes on the flags currently being sold are lying horizontally, whereas they should be positioned vertically. In addition, I do not remember seeing a ‘Votes for Women’ slogan imposed on a purple, white and green flag; they are invariably plain. I suspect that any analysis of the material and method of manufacture would indicate a 21st rather than early-20th century provenance.

The Women’s Library photographs do, of course, contain innumerable images of all manner of other banners and it was exactly because I am always so worried about fakery that when, in 2017, I spotted an amazing Manchester banner coming up for sale at a little-known auction house, I alerted first the Working Class Library and, through their archivist, the People’s History Museum because I thought it essential for a textile expert to inspect it in person in case somebody had taken it upon themselves to fake it. Fortunately, it was ‘right’ and now hangs in pride of place in the PHM.

The Manchester WSPU banner (image courtesy of the People’s History Museum)

And that is why I hope that no well-meaning donor will think of presenting their local museum with one of the spurious ‘Votes for Women’ flags for, by allowing the scammers to muscle in on our history, we are demeaning everything that is ‘right’.

Cynic that I am in such matters, I only hope this post does not encourage scammers to create more accurate reproductions.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement

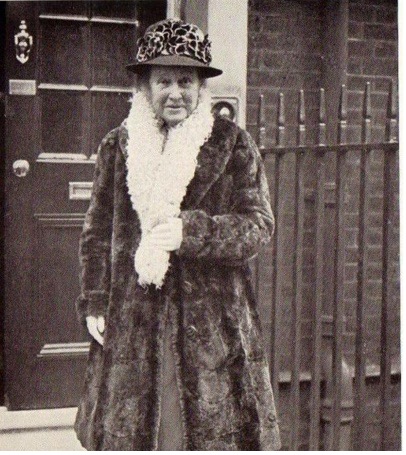

Collecting Suffrage: Photograph of Mrs Fawcett, 1890

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on September 3, 2020

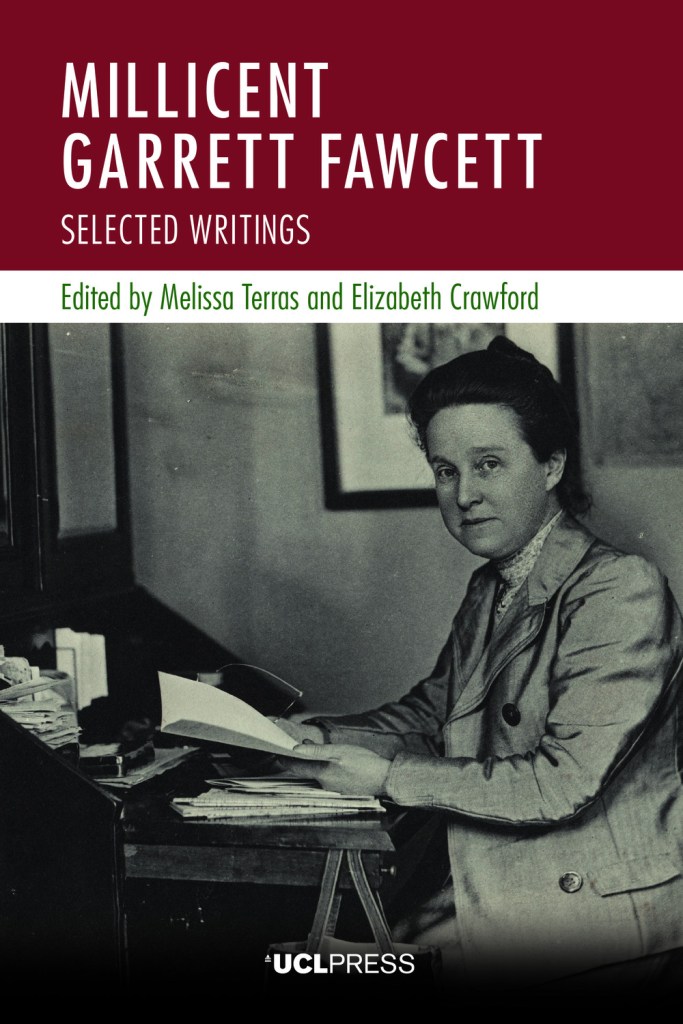

Today I offer you a studio photograph of Millicent Garrett Fawcett by W & D Downey. Published by Cassell & Co, 1890. She was 43 years old and had already been a leading light of the women’s suffrage movement for over 20 years.

A very good image – mounted. Suitable for framing. £40 + VAT in UK & EU.

In the past I have been concerned about the low profile afforded popularly to Mrs Fawcett. Indeed, in 2013 I wrote a post on the subject: Make Millicent Fawcett Visible.

And in 2016 when there was a suggestion that there should be a statue of a ‘suffragette’ in Parliament Square I did point out that there was already one nearby to Mrs Pankhurst (which I was also determined would not be moved) and one, so often forgotten, to the suffragette movement in general, just down Victoria Street in Christchurch Gardens. That resulted in another post – on Suffragette Statues.

As we all know, the idea of a ‘suffragette’ statue in Parliament Square morphed, thanks to input from Sam Smethers and the Fawcett Society, into the already well-loved statue of Mrs Fawcett. So that she is now indeed publicly visible.

Yesterday’s photograph of Mrs Pankhurst proved very popular, but if you would like demonstrate your loyalty to Mrs Fawcett, here is an excellent opportunity to acquire a photograph of her with which to adorn your desk or wall.

Do email me if you’re interested in buying. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

Collecting Suffrage: Photograph Of Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst c 1907

Posted by womanandhersphere in Collecting Suffrage on September 2, 2020

This photograph of Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst probably dates from c 1907, taken at her desk in Clement’s Inn, headquarters of the Women’s Social and Political Union.

The photograph comes from the collection of Isabel Seymour, who was an early WSPU supporter working in the WSPU office.

The photograph is mounted and is 15 x 20 cm (6″ x 8″) and is in good condition for its age. SOLD

Do email me if interested in buying. elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

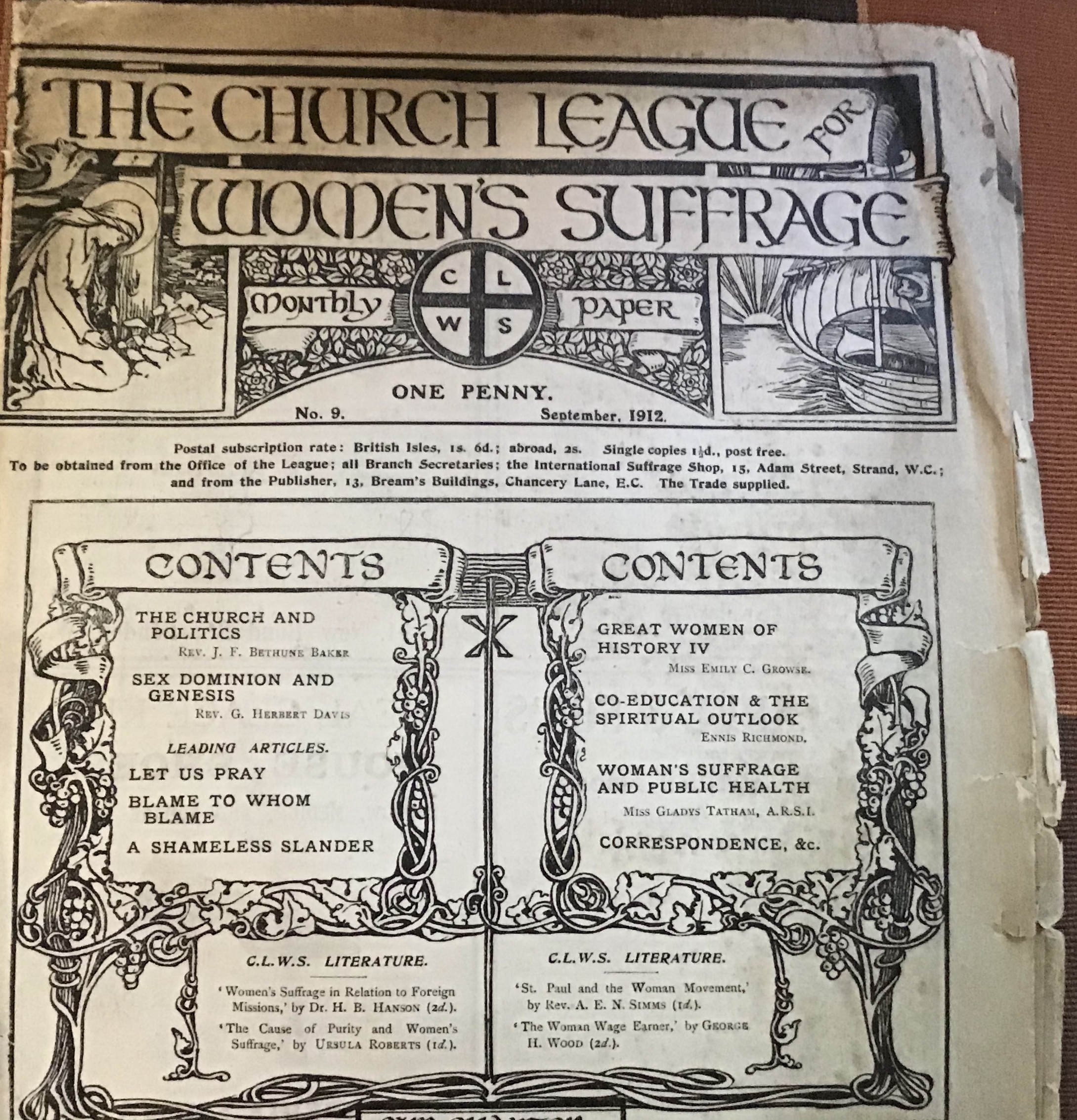

Collecting Suffrage: The Church League For Women’s Suffrage Paper

Posted by womanandhersphere in Books And Ephemera For Sale, Collecting Suffrage on August 5, 2020

The paper of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage was published monthly from January 1912. This is the issue for 9 September 1912. Issues of the paper are scarce and this one is in good condition for its age – packed with information. For sale – SOLD

If interested email me: elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

Kate Frye’s Diary: What Was Kate Doing One Hundred Years Ago Today – The Day She Appears On Our TV Screens?

Posted by womanandhersphere in First World War, Kate Frye's Diary on August 17, 2014

Tonight Kate Parry Frye – in the guise of Romola Garai – appears on our television screens (Sunday 17 August, ITV at 9pm). What was she doing on this day 100 years ago?

Kate was still on holiday from her work with the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage, spending the time with her sister and mother in their rented rooms at 10 Milton Street, Worthing. However, this was no summer idyll such as the Fryes had enjoyed in days gone by. Then they had rented a large house and travelled down from London with their four servants, to spend a season by the sea. Now that they were virtually penniless, these rented rooms were all they could call home. In the life of Kate and, more tragically in that of her sister, we see the jarring disconnect when young women, brought up to a life where marriage was to be their only trade, are left with insufficient money to support their social position and expectations. As such Kate’s life story is very much a tale of its time.

Monday August 17th 1914

Gorgeous day. Up and at house work. Out 12.30- just to the shops. Wrote all the afternoon and after tea to 6. Papers full of interest. Preparing for the biggest battle in the World’s History. There is no doubt the English have landed over there. I hear from John most days – that he is very busy but not a word of what his work is. Mickie [her Pomeranian] and I went out after tea. Agnes still a bit limp.

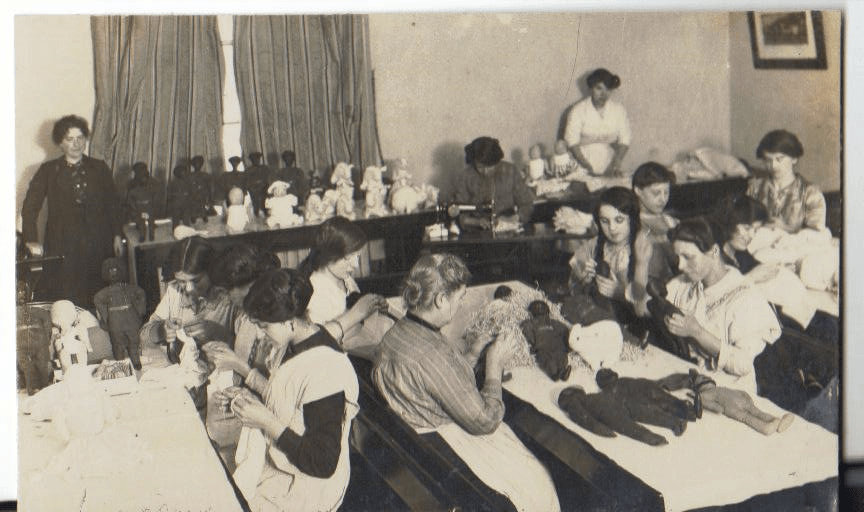

John Collins, Kate’s fiancé, who had long been an officer in the Territorial Army, had already been recalled to his barracks at Shoeburyness – leaving his engagement with a touring repertory theatre company. Kate’s sister, Agnes, at the first hint of the European trouble had taken to her bed, prostrate. Kate, a would-be playwright, was busy writing – although exactly what she was writing at this time she doesn’t divulge. On her death forty-five years later she left behind a box of unpublished scripts – and one that was published. She hoped one day to achieve fame and fortune. As it was she would soon be back at work at her suffrage society’s headquarters – with a new role as organizer of their War Work Work Room.

Work Room set up by the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage – of which Kate was in charge. Note the NCS flag in the background.

To discover more about the entirety of Kate’s life – her upbringing, her involvement with the suffrage movement, her marriage, her London flats, her life in a Buckinghamshire hamlet, her love of the theatre, her times as an actress, her efforts as a writer, her life on the Home Front during two world wars, her involvement with politics – and her view of the world from the 1890s until October 1958 – download the e-book – £4.99 – from iTunes – : http://bit.ly/PSeBKPFITVal. or £4.99 from Amazon.

I’d love to hear what you think of Kate and the life she lived.

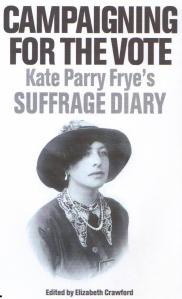

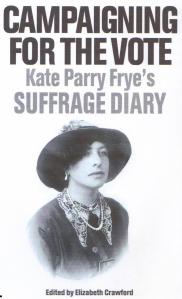

To read in detail about Kate’s involvement in the women’s suffrage campaign – in a beautifully-produced, highly illustrated, conventional paper book – see Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary.

Copyright

Campaigning For The Vote: Book Launch Invitation

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on May 9, 2013

Women Writers and Italy: Two Englishwomen In Rome and Sarah Parker Remond

Posted by womanandhersphere in Women Writers and Italy on March 30, 2013

Anne ( 1841-1928) and Matilda Lucas (1849-1943) were the daughters of Samuel Lucas, a brewer with land and influence in Hitchin, Hertfordshire. The Lucas family were Quakers. Their mother had died when they were young and after their father’s death in 1870 the sisters continued to live for a short time with their step-mother. But then, in mid-1871, they left England for Rome, where, for the next 29 years, they were to spend much of the year. Ten years after her sister’s death, Matilda Lucas published excerpts from the letters sent over the years by the sisters to friends and relations back in England. Two Englishwomen in Rome, 1871-1900 (Methuen, 1938) makes very interesting reading.

The few disingenuous sentences I transcribe below would appear to delineate the discomfort that must have been endured by Sarah Parker Remond (1824-94) , or Sarah Remond Pintor as she was by then, as she mixed in society – even expatriate Roman society, which was by no means ruled by convention. An American free-born black woman, Sarah Remond had lived for a time in London, signing the first women’s suffrage petition in 1866, perhaps the only black woman to do so, had then travelled to Italy, where she qualified as a doctor. She had married an Italian, Lazzaro Pintor in Florence in 1877. There is some debate as to how long the marriage lasted. From the Lucas’ evidence, Pintor did not accompany his wife to this social occasion in Rome in March 1878, but Sarah was sufficiently still married to feel able to don her bridal dress.

However am I correct, I wonder, to read the passage as reflecting the curiosity and, perhaps, also slight discomfort felt by the gathering at the presence of a black woman in their midst? If Sarah was their aunt the P___s must surely have been the ‘Putnams’ – the family of Sarah’s sister, Caroline Remond Putnam, who lived with her in Italy on various occasions. If so the fact that Caroline also was ‘black’ makes the passage a little difficult to interpret. Why was Sarah specifically their ‘black aunt’? Did they have any other kind? So perhaps it was only the bridal dress that was the cause for comment. A simple scene, but something of a puzzle.

March 17, 1878. Tell Madgie that the P___s were there with their black aunt. She was a bride, having just married an Italian, and wore her bridal dress of grey silk. It must have been very trying for Mrs P____. People came up to question her. One Italian said, ‘Chi e quell’Africana?’ It appears that she is very clever, and a female doctor. She was taken up a good deal in London by different people who were interested in negroes. I think she lived with the Peter Taylors. She has given lectures. I went to sit on the sofa with her, to the amusement of Franz, who cannot rise above her appearance. Dr Baedtke was much impressed to think that anyone has had the courage to marry her, and said, ‘In that I should have been a coward.’

Click here for Sarah Parker Remond: A Daughter of Salem, Massachusetts – a very interesting website

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery At The UNISON Centre

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on March 28, 2013

ALAS, IT WOULD APPEAR THAT THE GALLERY HAS FAILED TO REOPEN AFTER COVID CLOSURE. PLEASE PHONE UNISON TO ENQUIRE.

The Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery at the UNISON Centre tells the story of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, of the hospital she built, and of women’s struggle to achieve equality in the field of medicine.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) was determined to do something worthwhile with her life. In 1865 she qualified as a doctor. This was a landmark achievement. She was the first woman to overcome the obstacles created by the medical establishment to ensure it remained the preserve of men.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson then helped other women into the medical profession, founding the New Hospital for Women where women patients were treated only by women doctors.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, by her example, demonstrated that a woman could be a wife and mother as well as having a professional career.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson worked to achieve equality for women, being especially active in the campaigns for higher education and ‘votes for women’.

In the early 1890s the New Hospital for Women (later renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital) was built on the Euston Road and continued to treat women until 2000. For some years this building then lay derelict until a campaign by ‘EGA for Women’ won it listed status. UNISON has now carefully restored the building, bringing it back to life as part of the UNISON Centre.

Two important rooms in the original 1890 hospital building have been dedicated to the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery. One is the

ORIGINAL ENTRANCE HALL

of the hospital which has been carefully restored to its original form. Here you can study an album, compiled specially for the Gallery, telling the history of the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in words and pictures, while, in the background you can listen to a soundscape evocative of hospital life. This is interwoven with the reminiscences of hospital patients, snippets from the letters of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and sundry other sounds to stimulate your imagination.

The other Gallery room is what was known when the hospital opened as

THE MEDICAL INSTITUTE

This was a room, running along the front of the hospital, parallel to Euston Road, set aside for all women doctors, from all over the country, at a time when they were still barred from the British Medical Association. It was intended as a space in which they could meet, talk and keep up with the medical journals.

Here you can use a variety of media to follow the story of women, work and co-operation in the 19th and 20th centuries.

A BACK-LIT GRAPHIC LECTERN RUNS AROUND THE MAIN GALLERY:

allowing you to see in words and pictures a quick overview of the life of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and of her hospital.

AT INTERVALS ARE SET SIX INTERACTIVE TOUCH-SCREEN MONITORS

-named – Ambition, Perseverance, Leadership, Equality, Power in Numbers and Making Our Voices Heard – allowing you to access more information about Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, about the social and political conditions that have shaped her world and ours, and about the building’s new occupant – UNISON..

Each monitor contains:

TWO SHORT VIDEO SEGMENTS.

‘Elizabeth’s Story’. Follow the video from screen to screen. Often speaking her own words, the video uses images and voices to tell the story of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson’s life.

‘UNISON Now’ UNISON members tell you what the union means to them.

and four

INTERACTIVES

‘Campaigns for Justice’ and ‘Changing Lives’.

Touch the screen icons to discover how life in Britain has changed since the birth of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson.

AMBITION

Campaigns for justice

Victorian Britain: a society in flux

Victorian democracy: who could vote, and who couldn’t

Did a woman have rights?

Workers organised

Changing lives

The people’s lives in Victorian Britain

The medical profession before Elizabeth Garrett

Restricted lives, big ambitions: middle-class women in the Victorian era

Women workers in the first half of the 19th century

PERSEVERANCE

Campaigns for justice

The changing political landscape

Widening the franchise: can we trust the workers?

Women want to vote: the beginnings of a movement

Trade unions become trade unions

Changing lives

A new concept of active government: Victorian social reform

Women as nurses and carers

Living a life that’s never been lived before: women attempt to enter medicine

International pioneers: women study medicine abroad

LEADERSHIP

Campaigns for justice

Contagious Diseases Acts

Trade unions broaden their vision

Women and education

Women trade unionists

Changing lives

The middle-class century

Working women in the second half of the 19th century

Social reform, philanthropy and paternalism

Women doctors for India

EQUALITY

Campaigns for justice

The women’s suffrage movement

The Taff Vale decision hampers the unions

The founding of the Labour party

The People’s Budget

Changing lives

Work and play

Marylebone and Somers Town

Did the working classes want a welfare state?

1901 – Who were the workers in the NewHospital for Women?

POWER IN NUMBERS

Campaigns for justice

The General Strike – 1926

The first Labour governments

Feminist campaigns between the wars

1901: The lives of working women in London

Changing lives

Work of women doctors in the First World War

Can we afford the doctor? Health services before the NHS

Wartime demand for social justice

The creation of the National Health Service 1945-1948

MAKING OUR VOICES HEARD

Campaigns for justice

Equality campaigns

Public sector unions before UNISON

UNISON brings public service workers together

Are trade unions still relevant?

Changing lives

The National Health Service becomes sacrosanct

Did the welfare state change the family?

Women’s equality today

Women in medicine now

IN THE CENTRE OF THE GALLERY YOU WILL FIND:

ENTERPRISING WOMEN

an interactive table containing short biographies of over 100 women renowned for their achievements in Britain in the 19th-21st centuries. Up to four visitors can use the table at any one time. Drag a photograph towards the edge of the table to discover details of that individual’s life. Or search by name or vocation, using the alphabetical or subject lists.

ON THE WALLS OF THE GALLERY

PROJECTIONS

show a changing display of pictures of the hospital as it was and of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and some of the other women whose stories the Gallery tells.

is designed in the style associated with the work of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson’s sister, the architectural decorator Agnes Garrett, who was in charge of the original interior decoration of the hospital in 1890. The Gallery’s fireplace is the only surviving example of Agnes Garrett’s work. Next to this hangs a length of wallpaper, ‘Garrett Laburnum’, re-created from one of her designs.

In the Garrett Corner a display case and a low table contain a small collection of objects relevant to Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the hospital and early women doctors.

While here do sit down and browse the library of books. These relate to the history of women – in society, in medicine, in the workplace, and in trade unions – and to the Somers Town area.

Plaque commemorating a substantial donation to the hospital by Henry Tate, industrialist and philanthropist

ACROSS FROM THE GARRETT CORNER IS A DISPLAY OF CERAMIC PLAQUES

Decorative plaques that used to hang beside patients’ beds, each commemorating a donor’s generosity.

You can read in detail about the work of the Garrett family in the fields of medicine, education, interior design, landscape design, citizenship and material culture in Elizabeth Crawford, Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle, published by Francis Boutle Publishers, £25. The book can be bought direct from womanandhersphere.com or click here to buy from the publisher

DO VISIT:

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery at the UNISON Centre

130 Euston Road

London NW1 2AY

Telephone: 0800 0 857 857

Open Wednesday to Friday 9.00am to 6.00pm

and the third Saturday of every month 9.00am to 4.00pm

Admission Free

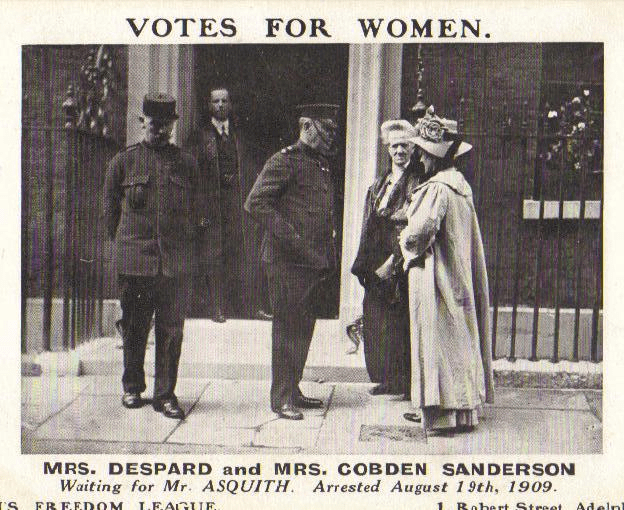

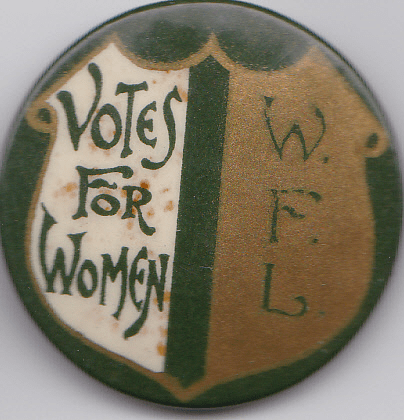

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: Palmist At The Women’s Freedom League Bazaar

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on December 10, 2012

By 1909 Kate Frye was keenly involved – as a volunteer – in the women’s suffrage campaign. Although she belonged to the constitutional London Society for Women’s Suffrage she was happy to give her services to other, more militant, suffrage societies – such as the Women’s Freedom League.

By 1909 Kate Frye was keenly involved – as a volunteer – in the women’s suffrage campaign. Although she belonged to the constitutional London Society for Women’s Suffrage she was happy to give her services to other, more militant, suffrage societies – such as the Women’s Freedom League.

Dramatis Personae for these entries

Marie Lawson (1881-1975) was a leading member of the WFL. An effective businesswoman, in 1909 she formed the Minerva Publishing Co. to produce the WFL’s weekly paper, The Vote.

May Whitty (1865-1948) and Ben Webster (1864-1947) were a well-established theatrical couple. Kate had toured with May Whitty in a production of J.M. Barrie’s Quality Street in 1903.

Ellen Terry (1847-1928) the leading Shakesperean actress of her age.

Edith Craig (1869-1947) theatre director, producer, costume designer, and a very active member of the Actresses’ Franchise League. She staged a number of spectacles for suffrage societies, working particularly closely with the Suffrage Atelier and the Women’s Freedom League. In January 1912 Kate appeared in Edith Craig’s production of The Coronation.

Lena Ashwell (1862-1957) actress, manager of the Kingsway Theatre, a vice-president of the Actresses’ Franchise League and a tax resister.

Thursday April 15th 1909 [The Plat, Bourne End]

I went up to London at 9.50 all in my best. Went to Smiths to leave the books – then straight from Praed St to St James Park by train and to the Caxton Hall for the 1st day of the Women’s Freedom League Bazaar. Got there about 11.30 – everything in an uproar, of course. I had to find out who was in authority over me and where I was to go to do my Palmistry. I had to find a Miss Marie Lawson first and then was taken to a lady who had charge of my department and she arranged where I was to go. A most miserable place it seemed – in a gallery overlooking the refreshment room. I meant to have gone out to have a meal first – but it all took me so long running about getting an extra chair etc that I should have missed the opening. Then another Palmist hurried up – the real thing who donned a red robe. I was jealous. Madame Yenda.

We got on very well, however, and exchanged cards (I have had some printed) it was all about as funny as anything I have ever done and I have had some experiences.

Then I went back to the main room which was beginning to get thronged and stifling from the smell of flash- light photographs. I discovered Miss May Whitty and Mr Ben Webster and chatted to them while we waited for Miss Ellen Terry who was half an hour late. Miss Whitty was awfully nice and I quite enjoyed meeting her again. Ellen Terry looked glorious in 15th century costume and was very gay and larkish. Her daughter Edith Craig was there to look after and prompt her – and ‘mother’ her – what a mother to have had. I expect she had to pay for it. She is a sweet-looking woman with a most clever face – only a tiny shade of her Mother in it but Ellen Terry took the shine out of everyone – what a face to be sure. When she went round the stalls I went to the Balcony and for a little time Madame Yenda and I tried to work up there together but it was impossible. All my clients had to disturb her as they walked to and fro so at last I came out to find 3 more Palmists waiting and nowhere for them to work. One, a real professional, was very cross especially at the small fee being charged and I don’t think she could have been there long. Two other girls, looking real amateurs, were also there. So I sat a while at a table outside and told a few but it wasn’t very satisfactory and at 2 o’clock I went out for some lunch leaving the four others there. I went into a Lyons place in Victoria Street and then went back a little before 3 o’clock meaning to have a look round the Bazaar but I was pounced on to begin again and I was alone at it all the afternoon from 3 till 5.45 up in the gallery. I was left at it with sometimes just a few minutes in between but must have told 40 hands I should say. I did about 7 or 8 before 2 o’clock. We were only supposed to give 10 minutes at the outside but I could not quite limit myself and sometimes, when there wasn’t a rush, I had long talks with the people. It was very interesting and on the whole I think I was successful. Train to Praed St and to Smiths for the books and home by the 6.45.

Friday April 16th 1909 [The Plat, Bourne End]

I went straight to Caxton Hall by train from Praed St to St James’s Park – left some flowers at the flower stall. Mother had packed up some lovely bunches for me. Then I went up to the l[ondon] S[ociety] for W[omen’s] S[uffrage] office on business connected with the Demonstration – then back to the Caxton Hall for the opening of the Green White and Gold Fair on the second day. Miss Lena Ashwell was punctual 12 o’clock and she looked delicious and did it all so nicely. Madame Yenda was there but no other Palmists. My chatty friend, who greeted me rapturously, helped fix up the gallery a much nicer place – but clients did not come very early -they were all following Lena Ashwell – so I had 1/- from Madame Yenda myself. I think she was clever but, of course, I am rather a hard critic at it. She told me a great many things I know to be absolutely true and she gave me some good advice especially about morbid introspective thoughts and I think she is quite right. I do over worry. I am to beware of scandal which is all round me just now. She predicts a broken engagement, a rich alliance and always heaps of money. I should have immense artistic success in my profession if only I had more confidence in myself and if only I had some favourable influence (a sort of back patter, I take it) to help me but such an influence is far away. I shall never live a calm uneventful existence. I shall always spend so much of myself with and for others. I am rather glad of that. I was just beginning to tell her her hand but I wouldn’t let her pay as she told me she was very poor and I could see it when some clients came for us both and we both had to start our work.

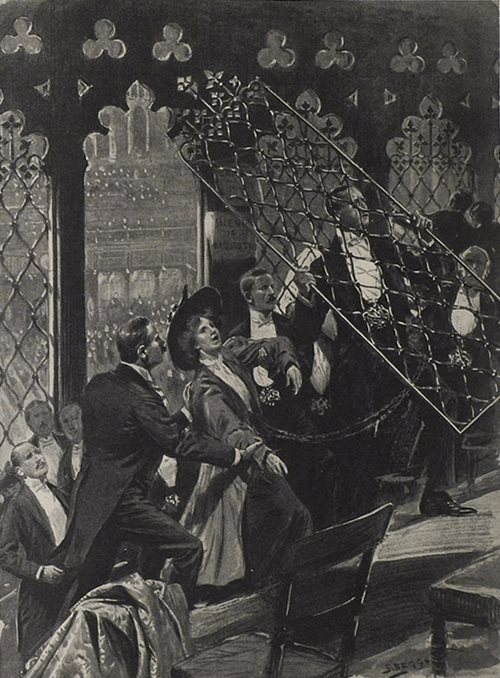

I didn’t feel a bit inclined for work at first but got into it and had wonderful success. Kept on till 2 o’clock – went to the Army and Navy Stores then and had some fish for lunch – then back – saw the ‘Prison Cell’ for 5 and was very interested – then started work at 2.45 and never moved off my chair till 6.15. I did have an afternoon of it. Madame Yenda had gone and I was alone in my glory. I must have had quite another 40 people if not more and they were waiting in line to come in to me. I seem to delight some of the people and one or two said I quite made them believe in Palmistry. One old lady came back for another shill’oth [shilling’s worth] as I had been so good with her past and present she wanted her future. I must have been very clairvoyant as I told the people extraordinary things sometimes and they said I was ‘true’. Of course one or two I could not make much headway with but that must always be so.

Where I found I had missed my train I wanted to go on but my chatty friend was really awfully decent and would not hear of it. She said if I would tell one man who had been waiting ever so long that was all I must do and she would send the others away. There were about 18 waiting and she did – rather to my relief. I felt ‘done’

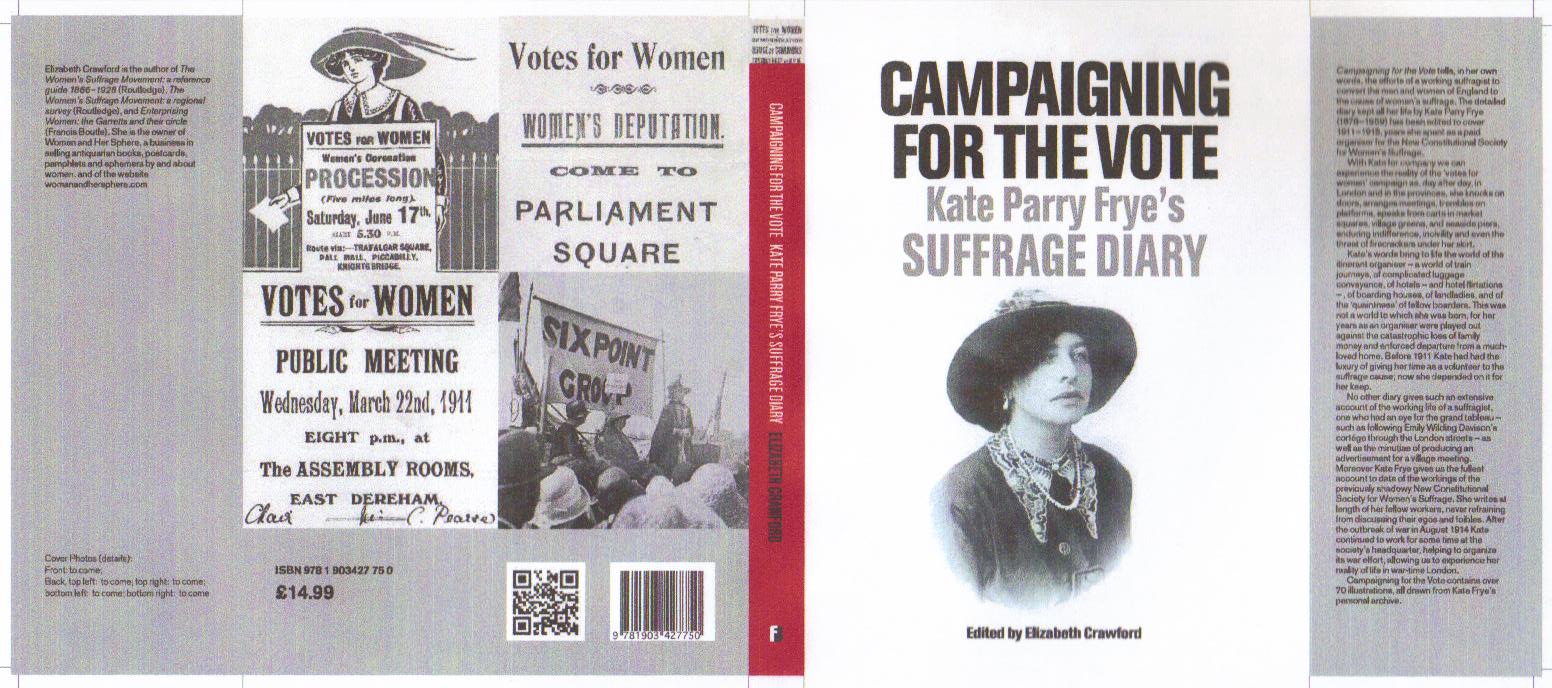

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

NOW, ALAS, OUT OF PRINT.

KATE FRYE’S DIARIES AND ASSOCIATED PAPERS ARE NOW HELD BY ROYAL HOLLOWA COLLEGE ARCHIVE

You can listen here to a talk I gave in the House of Commons – ‘Campaigning for the Vote: From MP’s Daughter to Suffrage Organiser: the diary of Kate Parry Frye’.

Copyright

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: The Mud March, 9 February 1907

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on November 21, 2012

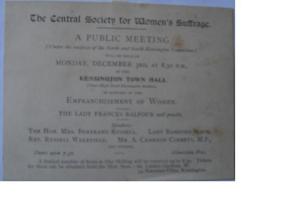

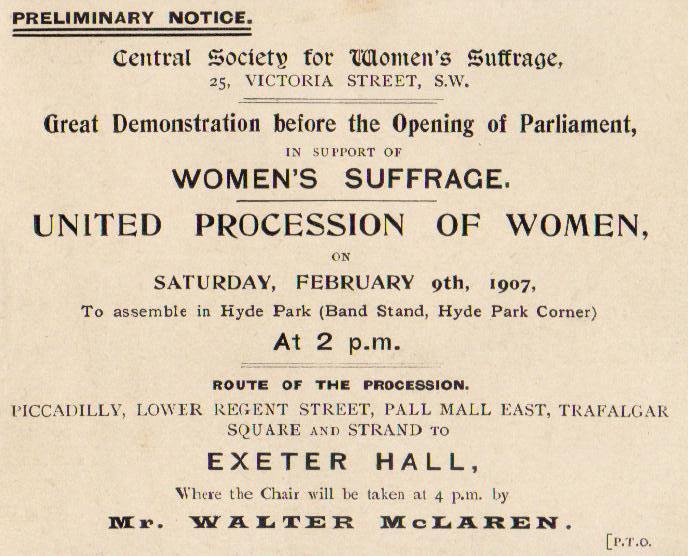

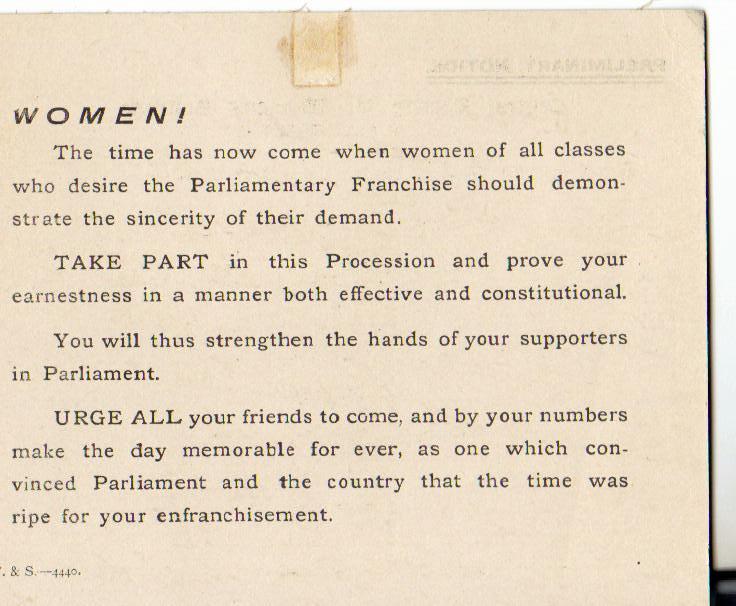

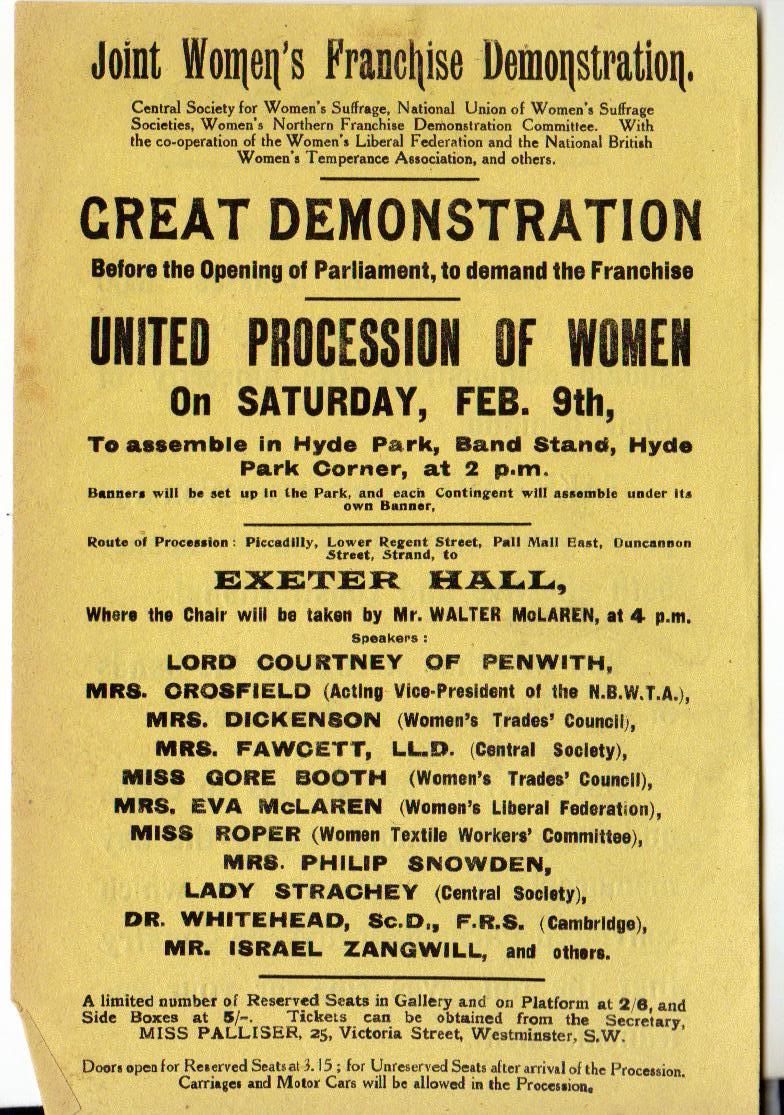

Kate Frye had first joined a suffrage society in the spring of 1906. Her choice was the Central Society for Women’s Suffrage (later renamed the London Society for Women’s Suffrage) – a constituent society of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies Interest in the long-running women’s suffrage campaign leapt ahead in the following few months and in February 1907 the NUWSS staged the first open-air suffrage spectacular – a march through the wintry, muddy London streets. For obvious reasons this became known as the ‘Mud March’. Kate’s estimate of 3000 participants accords with later reports.

Saturday 9 February 1907 [25 Arundel Gardens, North Kensington]

In bed for breakfast – and what was my utter disgust – and disappointment – to hear the torrents of rain – and there was not a shadow of its coming last night – it was bitterly cold. As it was so heavy I hoped it would stop – but it went on and on into a fine heavy drizzle. They said I should be mad to go in the procession and though I knew I must – I went out at 12.30 taking Mickie a walk and sent a telegram to Alexandra Wright telling her the rain prevented my joining them. I had arranged to be at their house at 1 o’clock and go with them to Hyde Park. We all had lunch. I knew I was going all the time – but couldn’t go. Off to wash my hands. 2 o’clock. ‘They will be just starting’, said I. Then as I washed I made up my mind I would go rain or no rain and – lo – the rain had ceased. I prepared a plan to Agnes. She too knew she was to be of it – both flew upstairs and were out of the house before 2.15.

In bed for breakfast – and what was my utter disgust – and disappointment – to hear the torrents of rain – and there was not a shadow of its coming last night – it was bitterly cold. As it was so heavy I hoped it would stop – but it went on and on into a fine heavy drizzle. They said I should be mad to go in the procession and though I knew I must – I went out at 12.30 taking Mickie a walk and sent a telegram to Alexandra Wright telling her the rain prevented my joining them. I had arranged to be at their house at 1 o’clock and go with them to Hyde Park. We all had lunch. I knew I was going all the time – but couldn’t go. Off to wash my hands. 2 o’clock. ‘They will be just starting’, said I. Then as I washed I made up my mind I would go rain or no rain and – lo – the rain had ceased. I prepared a plan to Agnes. She too knew she was to be of it – both flew upstairs and were out of the house before 2.15.

We tore to Notting Hill Gate – meaning to go the quickest way. No motor bus – so we tore for the train – it came in as I started to race down. In we scrambled – had to change at South Kensington much to our disgust – but we were not kept long. We flew out at Charing Cross and up Villiers Street. No sign of the Procession of Women Suffragists in the Strand. They were timed to leave Hyde Park at 2 o’clock so I had to pluck up my courage and ask a policeman. No, they had not passed. So, knowing the route, we flew up as far as Piccadilly Circus and there in about 2 minutes we heard strains of a band and waited, anxious and expectant. The crowd began to gather and we were nearly swept away by the first part – a swarm of roughs with the band – but the procession itself came – passed along dignified and really impressive. It was a sight I wouldn’t have missed for anything – and I was glad to have the opportunity of seeing it as well as taking part in it.

We stood right in front so as not to miss our contingent – and I asked if they knew where it was. Miss Gore Booth said it was coming and we were fearfully excited and I was so anxious not to miss our lot. I shrieked out when I saw Miss Doake’s red head in the distance and we dashed up to them and asked if we could join in. Alexandra carried our banner. Mrs Wright said come along here – it felt like boarding an express train but I suppose it was a quite simple rally though I cannot look back on it as that – but we were so excited and so anxious not to miss them. We walked three abreast – Miss Doake, Agnes and I – I was on the kerb side – behind us Gladys [Wright], Miss Ellis and Mrs Doake. North Kensington was not very well represented but I really do not know who else of us was there.

We stood right in front so as not to miss our contingent – and I asked if they knew where it was. Miss Gore Booth said it was coming and we were fearfully excited and I was so anxious not to miss our lot. I shrieked out when I saw Miss Doake’s red head in the distance and we dashed up to them and asked if we could join in. Alexandra carried our banner. Mrs Wright said come along here – it felt like boarding an express train but I suppose it was a quite simple rally though I cannot look back on it as that – but we were so excited and so anxious not to miss them. We walked three abreast – Miss Doake, Agnes and I – I was on the kerb side – behind us Gladys [Wright], Miss Ellis and Mrs Doake. North Kensington was not very well represented but I really do not know who else of us was there.

Then the real excitement started. The crowds to see us – the man in the street – the men in the Clubs, the people standing outside the Carlton – interested – surprised for the most part – not much joking at our expense and no roughness. The policemen were splendid and all the traffic was stopped our way. We were an imposing spectacle all with badges – each section under its own banners. Ours got broken, poor thing, unfortunately, and caused remarks. I felt like a martyr of old and walked proudly along. I would not jest with the crowd – though we had some jokes with ourselves. It did seem an extraordinary walk and it took some time as we went very slowly occasionally when we got congested – but we went in one long unbroken procession. There were 3000 about I believe. At the end came ever so many carriages and motor cars – but of course we did not see them. Lots of people we knew drove.

Flyer advertising the NUWSS ‘Mud March’

Flyer advertising the NUWSS ‘Mud March’Up the Strand it was a great crowd watching – some of the remarks were most amusing. ‘Here comes the class’ and two quite smart men standing by the kerb ‘I say look at those nice girls – positively disgraceful I call it.’ Then ‘Ginger hair – dark hair – and fair hair’ ‘Oh! What nice girls’ to Miss Doake, Agnes and I. Several asked if we had brought our sweethearts and made remarks to express their surprise at our special little band. ‘All the prizes in this lot’ etc. The mud was awful. Agnes and I wore galoshes so our feet were alright but we got dreadfully splashed. It was quite a business turning into the Exeter Hall. A band was playing merrily all the time – the one which had led the procession – and there was one not far off us. Three altogether, I was told.

Exeter Hall in 1905

Exeter Hall in 1905We got good seats and of course had to wait some time before the meeting started – it was just after 4 pm when it did – but there was a ladies’ orchestra performing and playing very well and a lady at the organ in between whiles. The meeting was splendid. Mr Walter McLaren in the Chair and Israel Zangwill as chief speaker – he was so splendid and most witty. Miss Gore Booth – Mrs Fawcett – Mrs Eva McLaren – Lady Strachey and several other ladies spoke and Keir Hardie made an excellent speech. It was altogether a wonderful and memorable afternoon – and felt we were making history – but after all I don’t know, I am sure, what will come of it. The MPs seem to have cheated and thoroughly ‘had’ us all over it. They wanted the Liberal Women’s help to get into the House and now they don’t care two straws or they are frightened of us. We walked up to Tottenham Court Road and came home by bus. It was nearly 7 o’clock when we got in. .. I felt bitterly tired all the evening after the excitement.

Dramatis Personae for this entry

Agnes, Kate’s elder sister

Mickie, Kate’s beloved dog

Alexandra and her sister, Gladys, lived at 10 Linden Gardens. It was under their influence that Kate had joined the London Society for Women’s Suffrage.

Violette Mary Doake (b 1888) her parents were Irish, which may account for the red hair. Her mother, Mary Elizabeth Doake, was also a suffragist. Her father, Richard Baxter Doake, described in the 1911 census as a ‘tea planter’, was elected as a Progressive party member in 1892 to the LCC seat relinquished by Frederick Frye. In 1901 the Doakes lived at 24 Stanley Gardens, close to the Fryes. By 1911 they had moved to 25 Ladbroke Gardens.

Walter McLaren and his wife, Eva were members of a family of long-standing supporters of women’s suffrage. He had been Liberal MP for Crewe in the 1890s and regained the seat in 1910.

Israel Zangwill, Jewish novelist and very effective writer and speaker in support of women’s suffrage

Lady Strachey had worked for women’s suffrage since the 1860s. She remarked that after this march she had to boil her skirt.

Keir Hardie, first Independent Labour Party MP. He had strongly supported a motion in favour of women’s suffrage at the Labour party conference on 26 January

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com (£14.99), or from all good bookshops.

- Campaigning for the Vote– Front and back cover of wrappers

You can also listen here to a Radio 4 programme as Anne McElvoy and I follow the route of the ‘Mud March’.

Copyright

Am I Not A Woman And A Sister: Women and the Anti-Slavery Campaign

Posted by womanandhersphere in Uncategorized on October 1, 2012

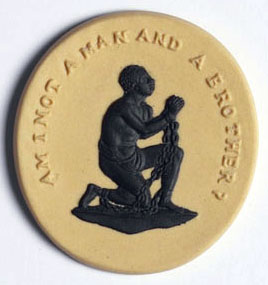

Am I Not a Woman and a Sister: women and the anti-slavery campaign

‘Am I not a woman and a sister’ reads the legend arching over the female figure of Justice as she reaches towards a kneeling black slave woman, who holds her chained hands up in supplication. In the 1830s this powerful emblem was used on printed matter and on artifacts associated with women-only, or ‘ladies’, anti- slavery associations. It very consciously echoed the motto, ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother’, adopted in 1787 by the founders of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Throughout the long years of abolitionist campaigning women were always participants, their role becoming, over the years, increasing prominent. Experience gained in a movement of such social, economic and political importance was to prove valuable when, in the 1860s, they launched the campaign to gain their own political freedom.

‘Am I not a woman and a sister’ reads the legend arching over the female figure of Justice as she reaches towards a kneeling black slave woman, who holds her chained hands up in supplication. In the 1830s this powerful emblem was used on printed matter and on artifacts associated with women-only, or ‘ladies’, anti- slavery associations. It very consciously echoed the motto, ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother’, adopted in 1787 by the founders of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Throughout the long years of abolitionist campaigning women were always participants, their role becoming, over the years, increasing prominent. Experience gained in a movement of such social, economic and political importance was to prove valuable when, in the 1860s, they launched the campaign to gain their own political freedom.

In 1787, however, women could take no direct part in politics, their role confined to that of exercising influence on those who did have political power. One such woman was Lady Middleton, a member of the evangelical Clapham Sect, who conducted a country-house salon at Barham Court in Kent. It was she who, according to Thomas Clarkson, in 1786 persuaded both William Wilberforce and himself to take up the anti-slavery cause. Lady Middleton’s own interest in the subject was not new. In 1782 she had been among the subscribers to Letters of Late Ignatius Sancho, the first prose work by an African to be published in England. Ignatius Sancho, born on a slave ship, had, as a child, been a house slave in London, at Greenwich.

Women’s influence extended to rather more than cajolery over the dinner table. Another member of the Clapham Sect, Lady Middleton’s close friend the writer Hannah More, was asked, in late 1787, to write a poem to draw attention to the discussion soon to take place in Parliament. She quickly composed Slavery, a Poem, published as a large, handsomely printed, 20-page book. She was just one of many women writers who wielded their pens in the abolitionist cause. Although they did not have direct power women could exercise their influence through the medium considered most suitable to their sex, poetry.

Women were also a valuable source of the finance necessary for the funding of the campaign. Although the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed and officered by men, there was no attempt to prevent women from becoming subscribers. Subscriptions ranged from one to five guineas, sizeable sums, indicating that those donating were drawn from the middling to wealthy section of society. Fortunately for us, the Society printed a report listing by name all its subscribers. Women clearly had no more qualms at having their names listed in such a quasi-political publication than they did in appearing as subscribers to a novel or volume of poetry. It is possible, therefore, to study the names of 206 women, comprising about ten per cent of the total, who in the late-18th century made public their condemnation of the slave trade.

The main, London-based, committee attracted members from all around the country. It is noticeable that there are few obviously upper-class or aristocratic women on the list. Only three titled ladies subscribed: Lady Hatton of Longstanton, the Dowager Countess Stanhope (who gave £50), and the Dowager Viscountess Galway. A superficial investigation would indicate that all three were women associated with families with radical sympathies. Indeed the Dowager Countess Stanhope’s son, who had succeeded her husband as earl, was soon to style himself ‘Citizen Stanhope’ to demonstrate his support for revolution in France. Two others of those listed, ‘Miss Pelham and Miss Mary Pelham of Esher’ were members of an influential Whig family, counting a former prime minister amongst their forebears.

The names of some subscribers have entered the literary canon. Prominent are Elizabeth Carter (writer and ‘blue stocking’), Sarah Trimmer (evangelical educationalist and writer) and Mary Scott of Milborne Port, Dorset, who in 1774 had written a lengthy poem, The Female Advocate, in which she drew attention to Phillis Wheatley, the first slave and black woman to have a book of poetry published in Britain.

Information can, with some application, be teased out about many of the other names on the list. A quick Google search reveals that, at random,’ Mrs Elizabeth Prowse of Wicken Park, Northampton’ was the sister of Granville Sharp, a leading member of the Abolition Committee. That ‘Mrs Peckard, Cambridge’ was, probably Martha, the wife of Peter Peckard, vice chancellor of Cambridge University and a preacher of sermons against the slave trade. It was he who, he in 1785 had set the question, ‘Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?’, for the University’s Latin essay won by Thomas Clarkson, the first step in his abolitionist career.

Through the Will Search facility at DocumentsOnline on the National Archives website it is possible to read the wills of some of the subscribers and discover a little more about their lives. For example, ‘Mary Belch, Ratcliffe’ was a corn chandler of Broad Street, Ratcliffe, in east London and ‘Deborah Townsend, Smithfield Bars’ was either the wife or the daughter of a Smithfield grocer. The wills may not reveal much about their abolitionist sympathies but they do demonstrate that women from this sector of society were committed to the cause.

The will of another subscriber, ‘Elizabeth Freeman, Woodbridge’, reveals that she was a Quaker and that she left ‘to my poor relations in America twenty pounds to be disposed of by friends of the Monthly Meeting in North Carolina’. It might be presumed that with these connections she knew something of conditions in an American slave state. Further research might indicate that other women subscribers from Woodbridge were also Quakers. Some names, of course, do indicate clear Quaker connections. Five female member of the well-known Fox family of Falmouth were subscribers and, with their fellow Quakers, are likely to be traceable through the records kept by the Society of Friends.

Women were also subscribers to the separate local committees formed in provincial towns. In Manchester 68 out of total of 302 subscribers were women. However few of the names include any indication of address and are, therefore, more difficult to identify. Some were wives of men involved with the Manchester committee. One such was ‘Mrs Bayley of Hope’, wife of Thomas Bayley, Unitarian, JP and penal reformer. Here too many the female subscribers were likely to have been nonconformists, particularly Unitarians and Quakers, a large number having connections with Manchester’s manufacturing interests.

In Bristol, notorious as a slave port, subscribers to the local committee included Miss Anna Goldney and ‘Mrs Goldney’. It has to be remembered that ‘Mrs’ at that time was a title given to unmarried as well as married women and, therefore, that the latter was probably Ann Goldney, who was unmarried and had recently inherited the family’s Clifton estate from her brother. The Goldneys were Quakers although an ancestor, Thomas Goldney, had, in the early 18th century, been the principal investor in a venture leading to the capture of slaves, the family fortune enhanced by investment in the manufacturing of guns for trade with Africa. Between them, Ann and Anna Goldney, a cousin living in the Clifton household, gave a generous six guineas.

Other Bristol women subscribers were Mrs Esther Ash, Mrs Frampton, Mrs Olive and Mrs Merlott, all of whom had at least one other thing in common, being subscribers in 1787 to a translation of Persian poems by Charles Fox. It is likely some were Quakers, but ‘Mrs Merlott’ was probably the unmarried sister of John Merlott, a Presbyterian sugar refiner.

Named women also subscribed to local committees in Birmingham, Exeter, Leeds and Leicester, some of which were probably set up with the encouragement of Thomas Clarkson as he acted as roving ambassador for the Abolition Society. He also organized mass petitions that were such a novelty of this campaign, an early manifestation of the method to be used by popular protest groups throughout the 19th century. Women, however, were not signatories. It was presumably thought that if they were the value of the petition would be diminished.

Women did, though, on occasion take part in public debates about the slave trade. One such was held in 1788 in La Belle Assemblée, a concert hall in Brewer Street, Soho, London, where ‘ladies were permitted to speak in veils’. In 1792 women were also present at a debate at the Coach-makers’ Hall, Foster Lane, Cheapside calling for the boycott of West Indian sugar and rum. The motion was carried by a unanimous vote of 600.

The subject of this latter meeting was one that women were making their own. For, although denied political power, they were able, at least in theory, to influence the economy. As early as 1788 Hannah More had urged a friend ‘to taboo the use of West Indian sugar in your tea’. Women, as chief purchasers of household goods, were encouraged to boycott slave-produced sugar from the West Indies, shopping instead for that grown in the East Indies by free labour. It is thought that by 1791-92 the sugar boycott affected as many as 300,000 people.

As well as redirecting their spending power to ‘free’ produce, women were also encouraged to purchase items that would proclaim their support for the abolitionist cause.

Thousands of Josiah Wedgwood’s ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother’ jasperware cameos were incorporated into brooches, bracelets, earrings and hair ornaments, allowing the wearer to indicate sympathy with the abolitionist cause. The ‘kneeling slave’ image was also rendered on a variety of other artefacts and was considered a very suitable subject for young girls to embroider on their samplers.

Women could also buy china bearing anti-slavery messages. The tea table was the sphere of influence particular to the woman of the house and, while entertaining her friends, she could pass round a sugar bowl bearing the motto, ‘East India Sugar not made/By Slaves/By Six families using/East India, instead of/West India Sugar, one/Slave less is required’. By boycotting West Indian sugar and displaying articles such as this she turned herself from a passive consumer into a political activist.

Women were able to demonstrate their sensibility by buying and subscribing to the slim volumes of abolitionist poetry that were finding a popular readership. These were written by women of all sorts and conditions, by, as already noted, the evangelical Hannah More, by her working-class protogée, Ann Yearsley, by Mary Robinson, ex-mistress of the Prince of Wales, and by a succession of young women, such as Mary Birkett of Dublin. Women were also able to educate the younger generation by purchasing works such as The Negro Boy’s Tale: a poem addressed to children, published by Amelia Opie in 1802.

By then, however, the mass popular campaign had collapsed. In 1792 the British public had watched in horror as the French monarchy was overthrown by the mob and, in the same year, slaves in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) rose up against their masters. Whatever its theoretical sympathy with the anti-slavery campaign, the British public had no wish to unleash similar forces. When the act abolishing Britain’s direct involvement in the slave trade was passed in 1807 it was as a result, not of popular protest, but of parliamentary manoeuvrings, in which, of course, women played no part.

There was no further popular agitation against slavery until 1823 when Wilberforce and Clarkson once again took the lead in the formation of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions. Over the intervening years there had been a decided change in the position of women who now had no inhibition about founding their own anti-slavery societies. The first such was formed in Birmingham in 1825. Here Lucy Townsend, the wife of an Anglican clergyman, worked with a Quaker, Mary Lloyd. Contact was made through their various denominational networks and soon towns such as Manchester, Sheffield, Liverpool, Bristol, Newcastle, York, Southampton and Plymouth, as well as London, supported ladies’ associations. There were also groups in Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

The formation of these societies and the activities they undertook did not escape criticism. Wilberforce expressed what one imagines was a very common view: ‘All private exertions for such an object become their character, but for ladies to meet, to go from house to house stirring up petitions – these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture’.

For women were now, indeed, a petitioning force. In the early 1830s hundreds of thousands of women signed petitions. Those presented in 1833 alone bore the signatures of 298,785 women, nearly a quarter of the total. A large number – 187,157 – were on a single petition circulated by the London Female Anti-slavery Society and presented to the House of Commons on 14 May 1833, the day the emancipation bill was produced.

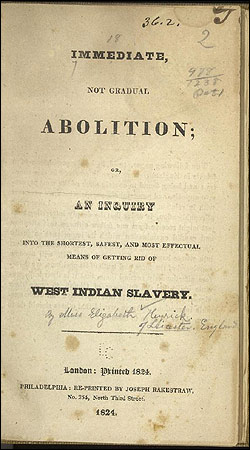

Women were not only, by petitioning, participating in the political process, but were now even questioning the aims of the movement. In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick, a Leicester Quaker, published a pamphlet, Immediate not Gradual Abolition, calling for immediate emancipation of slaves, in contradistinction to the Anti-Slavery Society’s aim of gradual emancipation. In 1830, at Elizabeth Heyrick’s suggestion, the influential Birmingham women’s society threatened to withdraw its funding from the Anti -Slavery Society if it did not agree to change its aim to immediate abolition. The change was agreed.

Women were not only, by petitioning, participating in the political process, but were now even questioning the aims of the movement. In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick, a Leicester Quaker, published a pamphlet, Immediate not Gradual Abolition, calling for immediate emancipation of slaves, in contradistinction to the Anti-Slavery Society’s aim of gradual emancipation. In 1830, at Elizabeth Heyrick’s suggestion, the influential Birmingham women’s society threatened to withdraw its funding from the Anti -Slavery Society if it did not agree to change its aim to immediate abolition. The change was agreed.

Elizabeth Heyrick was also the leader of a new campaign to boycott West Indian produce, especially sugar. Like that of the late-18th century, the 19th-century campaign appealed to the woman of the family to exercise her economic power. In 1828 the Peckham Ladies’ African and Anti-Slavery Association published Reasons for Using east India Sugar, demonstrating to its readers ‘that by substituting east India for west India sugar, they are undermining the system of slavery, in the safest, most easy, and effectual manner, in which it can be done’. ‘If we purchase the commodity, we participate in the crime. The laws of our country may hold the sugar-cane to our lips, steeped in the blood of our fellow-creatures; but they cannot compel us to accept the loathsome potion.’

Women also exercised their talents in order to raise funds for the cause. The bazaar became a particularly womanly form of demonstrating support. As ever, this activity was regarded in some quarters as a waste of effort. In a letter of 22 September 1828 the salon hostess, Mary Clarke Mohl, wrote: ‘My niece spends all her time making little embroidered bags to be sold for the Anti-Slavery Society …which would be all very well if, instead of turning seamstress to gain £10 a year, she put some poor woman in the way of work’.

Only three years after the Anti-Slavery Society had agreed to change its agenda, the 1833 Anti-Slavery Act abolished slavery within the British colonies. Although a period of apprenticeship was imposed on former slaves before they could obtain freedom, a determined effort by the abolitionists led, in 1838, to the early termination of this system. A national women’s petition on behalf of the apprentices addressed to the newly crowned Queen Victoria had carried the signatures of 7000,000 women, a number described as ‘unprecedented in the annals of petitioning’.

Although Britain no longer allowed slavery within its own territories the anti-slavery campaign continued, with the aim of abolishing slavery world wide. In 1840 the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society organized the first World Anti-Slavery Convention. Women delegates, among them a grand-daughter of Lady Middleton, arrived in London from all parts of Britain. From across the Atlantic came women belonging to a section of the US abolitionist movement that wished to combine anti-slavery activity with campaigns for women’s rights. All women were, however, denied participation in the proceedings. As might be expected that decision led not only to a split in the British anti-slavery movement but, indirectly, to the beginning of the US campaign for women’s suffrage. Several of the British women who were barred, women such Elizabeth Nicholls (later Pease), Hannah Webb, Maria Waring, and Matilda Ashurst Biggs, were among those who 26 years later signed the first women’s suffrage petition.

Both factions of the American anti-slavery movement were keen to gain support from British activists and throughout the 1840s and 1850s strong transatlantic links were developed. As in Britain, bazaars became a particular field of endeavour for American abolitionist women, with the British societies keen to supply boxes of goods for sale. In 1846 the Glasgow Society reported that at the Boston Anti-Slavery fair ‘every one of the great plaid shawls sold instantly. The beautiful cloaks sold, and also the bonnets. Aprons do well. The shawls sent by the Duchess of Sutherland sold immediately.’

The societies organized lecture tours for members of the American movement. In 1853 the Glasgow Society sponsored Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin had already sold 1.5 million copies in Britain and in 1861 the Edinburgh Society organized a series of lectures by Sarah Remond, whom they described as ‘a lady of colour from America.’ She wrote: ‘I have been received here as the sister of the white woman’.

Even after the ending of the American Civil War and the freeing of slaves in the US, British women’s societies continued their work, concentrating now on providing aid for the ‘Freedmen’. The Birmingham women’s anti-slavery society continued to meet until 1919.

Over the years many of the women’s anti-slavery societies printed reports, listing the members of their committees. It is now possible to study these, together with publications such as the Anti-Slavery Reporter, to discover not only who the women were who worked for this cause, but also to examine the clear links between the members of the abolitionist and of the women’s suffrage movements.

Further Reading

C. Midgley, Women Against Slavery: the British campaigns 1780-1870, Routledge, 1992.

Anti-Slavery International: http://www.antislavery.org .

Wilberforce House Museum, Hull: details of materials relating to the anti-slavery campaign can be found by searching for ‘Wilberforce House’ at http://www.cornucopia.org.uk .

http://www.quaker.org.uk contains an article on the Quaker involvement in the anti-slavery campaign. The library at Friends’ House, London, contains useful biographical records.

BBC History: Elizabeth Crawford, Women: From Abolition to the Vote

Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: Spring 1908 – Suffrage Hope – WSPU in Albert Hall ‘a little too theatrical but very wonderful’

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on September 26, 2012

Another extract from Kate Frye’s manuscript diary. An edited edition of later entries (from 1911), recording her work as a suffrage organiser, is published as Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s suffrage diary.

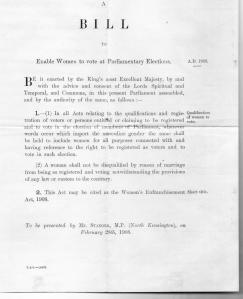

Kate’s MP, Henry Yorke Stanger, was the promoter of the current Enfranchisement Bill – the latest in the long line that stretched back through the latter half of the 19th century. Despite, as Kate describes, the bill passing its second reading, the government eventually refused to grant facilities to further the debate. However, that blow was yet to come as Kate records in these entries details of the suffrage meetings she attended in February and March 1908. She had the knack of always being present on the great occasions – and on 19 March was in the Albert Hall to witness the rousing – and profitable – reception given to Mrs Pankhurst on her release from prison.

Dramatis personae:

Miss Harriet Cockle, was 37 years old, an Australian woman of independent means, lving at 34 de Vere gardens, Kensington.

Mrs Philip Snowden – Ethel Snowden (1880-1951) wife of the ILP politician, Philip Snowden.

Mrs Clara Rackham (1875-1966) was regarded as on the the NUWSS’s best speakers. In 1910 she became president of the NUWSS’s Eastern Federation, was founder of the Cambridge branch of the Women’s Co-operative Guild, and was sister-in-law to Arthur Rackham, the book illustrator.

Margery Corbett (1882-1981- later Dame Margery Corbett-Ashby) was the daughter of a Liberal MP. At this time she was secretary of the NUWSS.

Mrs Fanny Haddelsey,wife of a solicitor, lived at 30 St James’s Square, Holland Park.

Mrs Stanbury had been an organiser for NUWSS as far back as 1890s.

Tuesday February 25th 1908 [London-25 Arundel Gardens]

We got home at 5.15 and had tea. Then I did my hair and tidied myself and Agnes and I ate hot fish at 6.30 and left soon after in a downpour of rain for the Kensington Town Hall – we did get wet walking to the bus and afterwards. We got there at 7 o’clock to steward – the doors were opening at 7.30 and the meeting started at 8.15. I was stewarding in the hall downstairs and missed my bag – purse with 6/- and latch Key etc – very early in the evening which rather spoilt the evening for me as I felt sure it had been stolen. It was a South Kensington Committee of the London Society for Woman’s Suffrage and we were stewarding for Miss Cockle. It was a good meeting but not crowded but, then, what a night. Miss Bertha Mason in the Chair. The speech of the evening was Mrs Philip Snowdon, who was great, and Mrs Rackham, who spoke well. The men did not do after them and poor Mr Stanger seemed quite worn out and quoted so much poetry he made me laugh. Daddie had honoured us with his presence for a little time and had sat on the platform – so I feel he has quite committed himself now and will have no right to go back on us. We were not in till 12.20 and then sat some time over our supper.

Wednesday February 26th 1908

Before I was up in the morning Mother came up in my room with my bag and purse and all quite safe. It had been found and the Hall Door Keeper had brought it. I was glad because of the Latch Key. Daddie generously had paid me the 6/- which I was able to return.

Friday February 28th 1908

Mr Stanger’s Woman’s Suffrage Bill has passed the second reading. I had to wait to see the Standard before going to my [cooking] class. That is very exciting and wonderful – but of course we have got this far already in past history. Oh! I would have liked to have been there.

MargWednesday March 11th 1908

To 25 Victoria Street and went to the 1st Speakers Class of the N.[ational] S.[ociety] of W.[omen’s] S.[uffrage]. I was very late getting there and there was no one I knew so I did not take any part in the proceedings and felt very frightened. But Alexandra Wright came in at the end and I spoke to Miss Margery Corbett and our instructoress, Mrs Brownlow. And then I came home with Alexandra from St James’s Park station to Notting Hilll Gate.

Thursday March 12th 1908

Mother went to a Lecture for the NKWLA [North Kensington Women’s Liberal Association] at the Club and Agnes and I started at 8 o’clock and walked to Mrs Haddesley [sic] for a drawing-room Suffrage Meeting at 8.30. Agnes and I stewarded and made ourselves generally useful. The Miss Porters were there and a girl who I saw at the Speakers’ Class on Wednesday. Alexandra was in the Chair and spoke beautifully – really she did. And Mrs Stanbury spoke. Mrs Corbett and Mrs George – all very good speakers. Mrs Stanbury was really great and there were a lot of questions and a lot of argument after, which made it exciting. It was a packed meeting but some of the people were stodgy. Miss Meade was there with a friend – her first appearance at anything of the kind she told us and she said it was all too much for her to take in all at once. The “class” girl walked with us to her home in HollandPark and we walked on home were not in till 11.45. I was awfully tired and glad of some supper and to get to bed.

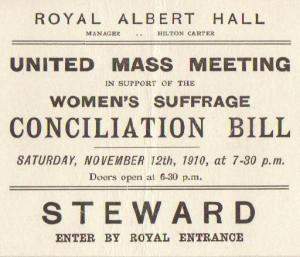

Mrs Pankhurst had been arrested on 13 February as she led a deputation from the ‘Women’s Parliament’ in Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. She was released from her subsequent imprisonment on 19 March, going straight to the Albert Hall where the audience waiting to greet her donated £7000 to WSPU funds. Kate was there.

Thursday March 19th 1908

I had a letter in the morning from Miss Madge Porter offering me a seat at the Albert Hall for the evening and of course I was delighted….just before 7 o’clock I started for the Albert Hall. Walked to Notting Hill gate then took a bus. The meeting was not till 8 o’clock but Miss Porter had told me to be there by 7 o’clock. We had seats in the Balcony and it was a great strain to hear the speakers. It was a meeting of the National Women’s Social and Political Union – and Mrs Pankhurst, newly released from Prison with the other six was there, and she filled the chair that we had thought to see empty. It was an exciting meeting. The speakers were Miss Christabel Pankhurst, Mrs Pethick Lawrence, Miss Annie Kenney, Mrs Martel and the huge sums of money they collected. It was like magic the way it flowed in. It was all just a little too theatrical but very wonderful. Miss Annie Kenney interested me the most – she seems so “inspired” quite a second Joan of Arc. I was very pleased not to be missing so wonderful an evening and I think it very nice of Miss Porter to have thought of me. She is quite a nice girl of the modern but “girlie” sort – a Cheltenham girl and quite clever – but very like a lot of other girls. Coming out we met, strangely enough, Mrs Wright and Alexandra (Gladys was speaking at Peckham) and after saying good-bye to Miss Porter I walked home with them as far as Linden Gardens. Got in at 11.30 very tired indeed and glad of my supper. Mother was waiting up.

Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary edited by Elizabeth Crawford

For a full description of the book click here

Wrap-around paper covers, 226 pp, over 70 illustrations, all drawn from Kate Frye’s personal archive.

ISBN 978 1903427 75 0

Copies available from Francis Boutle Publishers, or from Elizabeth Crawford – e.crawford@sphere20.freeserve.co.uk (£14.99 +UK postage £3. Please ask for international postage cost), or from all good bookshops. In stock at London Review of Books Bookshop, Foyles, National Archives Bookshop.

Kate Frye’s Diary: Canvassing for the Progressives in North Kensington,1907

Posted by womanandhersphere in Kate Frye's suffrage diary on September 13, 2012

Another extract from Kate Frye’s manuscript diary. An edited edition of later entries (from 1911), recording her work as a suffrage organiser, is published as Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s suffrage diary.

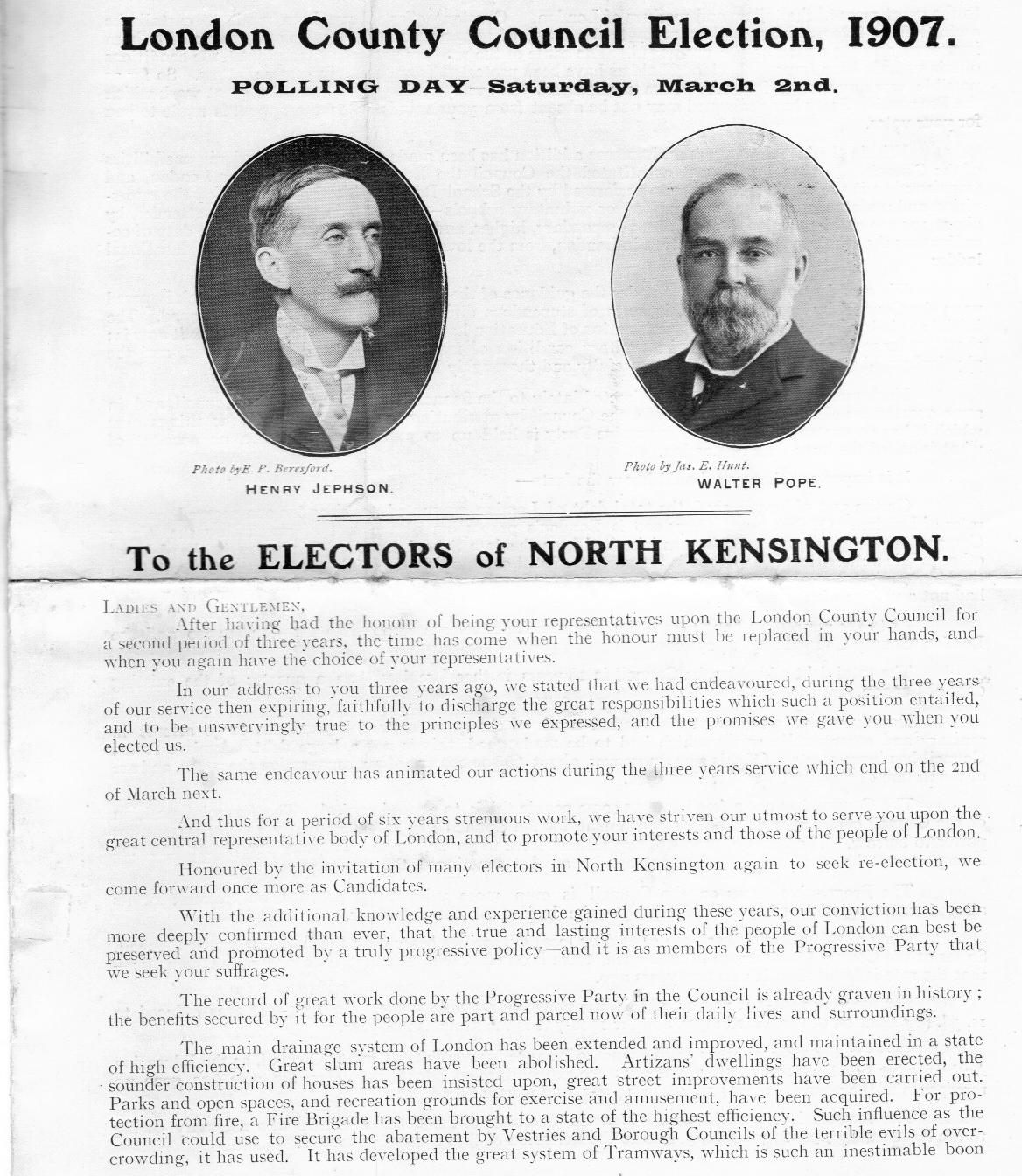

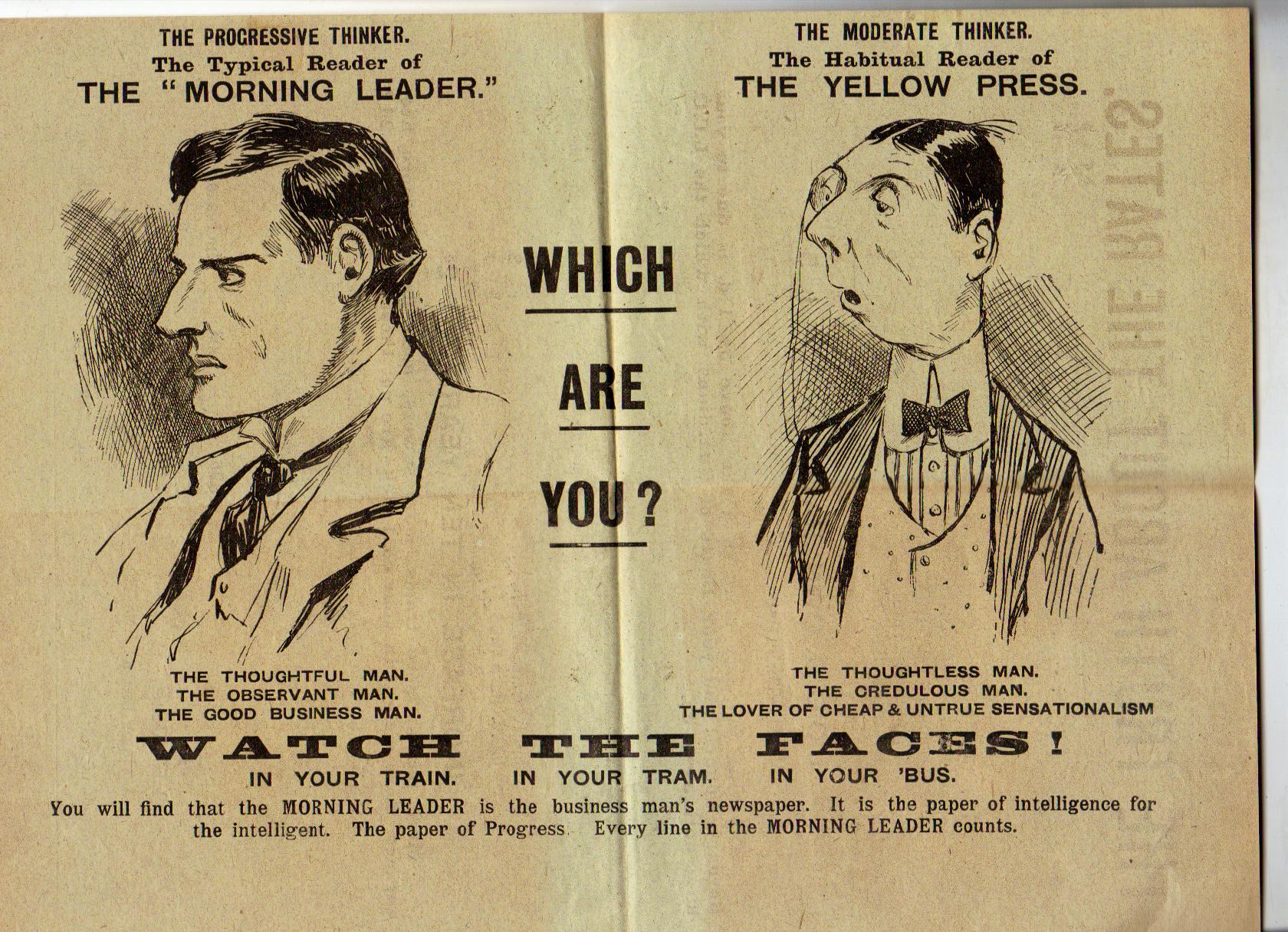

The ‘Morning Leader’ supported the Progressives and in late-February 1907 Kate laid this leaflet in between the pages of her diary