Posts Tagged camberwell

Mariana Starke: The De-Ciphering Of Mrs Crespigny’s Diary – And What It Reveals

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on September 4, 2023

In 2011 I made an enjoyable flying visit to Oxford to spend a few hours in the Bodleian Library reading quickly through a diary that the Library had lately acquired, a 1791 ‘Ladies Pocket Journal’, catalogued as having been written by a ‘Mrs Starke’.

As a result, I was able to identify the writer of the diary not as ‘Mrs Starke’ but as Mrs Mary Crespigny (1750-1812), patron and friend of Mariana Starke (see The Mystery of the Bodleian Diary). But I was unable to explain why, throughout the year, the male figure dominating the entries, whom in my innocence I assumed to be her husband, was referred to as ‘Starke’.

When I mention that many of the entries were written in a form of cipher, that in my original post I remarked that ‘It only now requires a cryptographer to set to work to decode the sections that she wished to keep safe from prying eyes’, and that, twelve years later, my wish has been granted, you may well see where this is going.

For I am now in possession of both a key to the cipher and a rough translation of the coded entries, which reveals beyond a peradventure that Mary Crespigny had formed ‘an attachment’ to Richard Starke, Mariana’s younger brother. Writing his name – ‘Starke’ – in plain text, Mrs Crespigny notes his presence almost every day – and evening – at Champion Lodge, the Camberwell home she shared with her husband, Claude Crespigny. Even if absent, Starke’s whereabouts are noted. In the coded passages his name is never spelled out, but it is clear that it is ‘Starke’ who is at the centre of Mrs Crespigny’s world. ‘Mr C.’ is occasionally mentioned, invariably favourably, but it is not on him whom her thoughts are concentrated.

Richard Isaac Starke was baptized at Epsom on 4 January 1768 and so in 1791 was 23 years old, eighteen years younger than Mary Crespigny, and three years younger than her only son, William. A member of the 2nd Regiment of Life Guards, Starke was promoted lieutenant in May 1791, his responsibilities not, apparently, particularly arduous. At intervals he undertook unspecified guard duties, which, on one occasion in February 1791, involved accompanying the King to the Opera.

The first mention I can uncover linking Richard Starke and Mary Crespigny is a notice in the 7 April 1789 issue of The Times, reporting that ‘At Mrs Crespigny’s temporary theatre at her house at Camberwell Miss Starke and Mr Starke took part in The Tragedy of Douglas’. The other actors, all amateurs, included William Crespigny as ‘Douglas’, the lost son of the heroine ‘Lady Randolph’, who was played by Mrs Crespigny to Richard Starke’s ‘Lord Randolph’. It is likely, however, that Richard Starke and Mary Crespigny were already well acquainted. Although I assume that it was through his sister that Richard Starke entered Mrs Crespigny’s orbit, I do not know when exactly the two women first met. Mrs Crespigny was certainly the inspiration for Mariana’s long poem, The Poor Soldier, published in March 1789, a month before the theatricals, and that work must have been a good while in the gestation. In fact, in her dedication, Mariana describes Mrs Crespigny as having ‘long honoured’ her with ‘flattering, though undeserved partiality’. Anyway, even if they had not done so previously, while playing husband and (unhappy) wife in Douglas, Richard Starke and Mary Crespigny had every opportunity to bond.

The following year, in April 1790, Richard and Mariana Starke again took part in Mrs Crespigny’s private theatricals. This time Mariana was the author, the play The British Orphan, never published, is now known only through a lengthy description in The Town and Country Magazine (vol 22, 1790). Mrs Crespigny was again the heroine and was particularly noted by the European Magazine and Theatrical Journal (April 1790) as appearing in three different dresses. Richard Starke played one of two friars, the other being R.J. S. Stevens, a composer who for the production set to music a poem written by Mariana. In his Recollections of a Musical Life (p.70) Stevens observed that Mrs Crespigny had wanted Caroline, a daughter of Lord Thurlow, to sing in this piece but, when consulted by Lord Thurlow, he (Stevens) disapproved ‘and I was inflexible. Private Theatricals I have ever considered as a species of entertainment very injurious to young minds; destructive of their innocence and modesty; and equally endangering their peace and happiness.’ When quoting this in my previous post about The British Orphan I did not know what I now know. Perhaps the Camberwell frolics had helped shape Stevens’ attitude.

Despite his Life Guard duties, Richard Starke not only had the time and inclination to take part in theatricals but had also put his pen to work, writing the epilogue to Mariana’s next play, The Widow of Malabar, which was given its first public performance, at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, a month after the staging of The British Orphan. The printed edition of The Widow of Malabar carries a dedication by Mariana to Mrs Crespigny, dated 24 January 1791. The first full entry in Mrs Crespigny’s 1791 diary would appear to indicate that she attended a production of The Widow of Malabar on 12 January – and may have gone again on the 19th. Even if she did not attend in person, she made sure that ‘Miss Starke had a very full house. I sent vast numbers – filled 10 rows of pit & nearly all the Boxes…’ On 16 February she wrote in her diary: ‘My wedding day – been married 27 years – We dined without company – Starke and I went to the Widow of Malabar in the eve.’ How conventional I was to think that on her wedding anniversary it was with her husband that she attended the play.

However, the cipher entries make clear that the ‘attachment’ (as she often refers to it) was tempestuous. She records frequent quarrels and tiffs. For instance, in March,

‘[Starke] and I were very happy till sometime after supper when he grew peevish and we tiff’d. He certainly rather cut and he is then generally out of humour. He said I was the wretchedest creature upon Earth – that he lived a wrong life….We made it up and the next morn were as good friends as ever.’

That is the pattern; it must have been very wearing. Doubtless it was the ‘making up’ that fuelled the affair. I suspect that a not-infrequent marginal mark records the instances of ‘making up’.

However, throughout the year Starke’s ‘propensity for drinking’ and womanising – with at least one prostitute (‘he told me that he had been naughty and taken a dolly out of the street to his own room…he told me he wd not go to any of the houses…what signifies it to me for this proves that his forbearance is at all end as we had not had the least quarrel nor was the least in liquor’) – caused Mary Crespigny great distress. While, as I’ve mentioned, she had no qualms about recording Starke’s constant presence in her plain text diary entries, Mary Crespigny confines her anguish to cipher. After one incident she wrote in code that ‘I complained to his sister tho very sorry to do so – she behaved vastly well and determin’d if he gave me further uneasiness that his mother [should] speak to him.’ The next words translate as ‘Mrs Stake’ – but can only mean ‘Mrs Starke’. So, here is the clearest evidence that not only was the ‘attachment’ known to Mariana, but that she knew that her brother used her patron ill.

The ’attachment’ was still in place at the end of December 1791 and we do not (for the moment, at least) know how it ended. But end it did. Richard Starke married in 1798 – not that that would necessarily prove anything – and Mary Crespigny’s only other surviving journal – covering April 1809-December 1810 – makes no mention of any Starke, either brother or sister. It does, however, frequently allude to her husband, now Sir Claude de Crespigny, and her son, William, who, with his family, received only a couple of mentions in 1791. And, interestingly, it contains no cipher entries. Presumably Mary Crespigny now had nothing to hide.

A ‘complaisant husband’?

That this lens through which to peer into late-18th-century life as actually lived should have been offered by Mary Crespigny is particularly pleasing, as it is as the author of a guide to a young man’s conduct that her literary fame rests.

Letters of Advice from a Mother to her Son was published in 1803, although Mary Crespigny’s dedication, to the Archbishop of Canterbury, claims the letters were originally written for ‘partial instruction to a beloved Son’ and, before publication, ‘remained by me many years unthought of…’ If that were so we could conclude, from the content, that they had been written when William was around 16 or 17 years old – perhaps circa 1782. The surprisingly frank essays treat matters religious, sexual, and socially practical. Of these one, Letter XXVII, headed ‘Attachment’, appears particularly relevant to Mrs Crespigny’s situation as revealed in her 1791 diary.

She states:

‘the uneasiness we are entangled in, for which accuse fortune or abuse others, is generally the offspring of our crimes or imprudence; by giving way impetuously to improper passion, we ourselves inflict the wound that is afterwards our torment: -no crime or folly is more likely in the end to produce this torment, than a forbidden attachment, which too often pursues its fatal course, at first, possibly, under the appearance of friendship; – and, by degrees almost imperceptible, it is then suffered to become that forbidden attachment, which, if its insinuating poison is not well guarded against, will certainly destroy the feelings of honour, truth, and virtue, and render the self-devoted victim a wretched slave to duplicity, falsehood, and criminality….Too often the person committing it is one in whom the greatest confidence is placed – the apparent friend of the family, daily partaking of its hospitality, and, with a seared conscience, receiving its favours….To be received into a house, to be treated there by the master of it with hospitality, kindness, and friendship, possibly to receive favours from him…to return all this with duplicity….is such a breach not only of hospitality, but every tie moral and divine…’

Whether this ‘Letter’ was written in the 1780s, well before the Starke adventure (although who is to say she had not had previous such ‘attachments’?), or whether written nearer the date of publication, in which case we know she was able to speak of ‘torment’ from experience, one might feel that Mary de Crespigny was taking something of a risk in moralising so sternly on the subject. For, eighteen years or so earlier, her ‘set’ could have had few doubts as to the nature of her relationship with the young man who lived in her house and accompanied her around town. In fact, the reviewers gave far more consideration to her views on religion or duelling or idleness than on ‘Female Connexion’, of which ‘Attachment’ was an element. However, The Critical Review (vol 1, 1804) did praise her for taking ‘off the mask which disguises some of her sex; we wish she had done it more generally; but she probably knows nothing of the worst part.’

Contrast that pious sentiment with this October 1791 entry, in cipher, in Mary Crespigny’s diary:

‘ He took me into another room and told me that he had been very foolish that a woman at a window had nodded to him and he went to her – how changed must be he feel towards me and how little attention he pays to my happiness any way – when assaild by strong temptation or when absent and when he has drunk too much he may have some excuse but after what has pass’d between us and while he chuses to continue to live with me he ought to pay some attention to my feel[ings] – shew some forbearance. It wd at any rate be mean[?] in to continue attach’d to him as I have been for he is clearly tired of me and he now gives way to what dear Mr C says is Libertism. I will suppress my feel[ings] – so far as not to make him an outcast from the house that wd be ruin to him but I am resolved to conquer my ill placed attachment to him and be only upon common terms with him.’

Knowing that Mary Crespigny was indeed well aware of ‘the worst part’, I wonder if this makes her observations as to the conduct to be expected of a young gentleman more or less persuasive?

In fact, a reading of the plain and cipher text of Mrs Crespigny’s 1791 ‘Pocket Journal’ provokes any number of questions around attitudes to morality held by her contemporaries. As such it will surely prove an interesting new resource for historians of late18th-century ‘upper-middling’ society.

Bodleian Reference for Mrs Crespigny’s 1791 diary.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere and are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement.

With thanks to the anonymous cryptographer who cracked Mrs Crespigny’s cipher and to Nigel à Brassard for generously sharing the resulting key and text.

Mariana Starke: Toxophilia – And Then To Italy, 1791

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on June 26, 2014

1791 was a most important year in the life of Mariana Starke.

We last met her in January of that year when, with her friend and patron, Mrs Crespigny, she attended her play, The Widow of Malabar, on the first night of its second season at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden.

Mrs Crespigny’s diary reveals that during the next few months she and Mariana met frequently – sometimes in Camberwell and sometimes in Epsom. Among their circle were the family of Henry Martin, who had become Comptroller of the Navy in 1790 and the news of whose baronetage Mrs Crespigny noted in her diary on 21 June 1791.

The Martins had at one time lived at Ashtead, a short distance down the Dorking Road from the Starkes’ Hylands House, but were probably now resident at Little Farm, near Tooting. ‘Miss Martin’ – presumably the eldest of his four daughters – was frequently included in parties to the theatre and opera and Mrs Crespigny mentions dining with Mrs Martin, together with Mariana, on 4 April, a day she described as ‘the first shooting day at Epsom’.

Mrs Crespigny’s diary relates that she and Mariana next met in Camberwell on 2 May – when they were joined by ‘Thomas on his matrimonial business’. This ‘Thomas’, I am sure, refers to the Rev Joseph Thomas for, on 6 May, ‘Miss Parkhurst dined and slept here’. Millecent Parkhurst, Mariana’s very close friend and co-author, was soon to marry the Rev Thomas. I cannot, though, explain why the Rev Thomas was discussing ‘matrimonial business’ – apparently in Millecent’s absence – with the inhabitants of Grove House. On 7 May, after dinner, Mariana and Millecent returned to Epsom.

Mariana was back at Grove House on 24 May and on the 25th Mrs Crespigny notes that she ‘gave my first archery party’. Mrs Crespigny was a keen archer – for excellent articles about this aspect of her life see A toxophilite – Mary de Crespigny née Clarke (1749 – 1812) and, for another much older article, here.

![After John Emes & Robert Smirke To His Royal Highness George Prince of Wales This Plate representing a Meeting of The Society of Royal British Archers in Gwersyllt Park, Denbighshire, aquatint by Cornelis Apostool, [Siltzer p.335], 1794, John Emes. The scene illustrates the popularity of the Royal British Archers, or Royal Toxophilite Society, amongst women (albeit only of a high social standing) as one of the few sports in which they compete at all, let alone on equal terms. The original painting is in the British Museum, the landscape being the work of Robert Emes, who also published the print, while the figures were painted by Robert Smirke. Retrieved from http://www.bloomsburyauctions.com/detail/13420/1154.0. Image and caption courtesy of A toxophilite - Mary de Crespigny née Clarke (1749 - 1812) see http://ayfamilyhistory.blogspot.co.uk/](https://womanandhersphere.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/royal-toxophilite-society-1794.jpg)

After John Emes & Robert Smirke To His Royal Highness George Prince of Wales This Plate representing a Meeting of The Society of Royal British Archers in Gwersyllt Park, Denbighshire, aquatint by Cornelis Apostool, [Siltzer p.335], 1794, John Emes. The scene illustrates the popularity of the Royal British Archers, or Royal Toxophilite Society, amongst women (albeit only of a high social standing) as one of the few sports in which they compete at all, let alone on equal terms. The original painting is in the British Museum, the landscape being the work of Robert Emes, who also published the print, while the figures were painted by Robert Smirke. Retrieved from http://www.bloomsburyauctions.com/detail/13420/1154.0. Image and caption courtesy of A toxophilite – Mary de Crespigny née Clarke (1749 – 1812) see http://ayfamilyhistory.blogspot.co.uk/

On Monday 21 August Mrs Crespigny spent the night at Hylands House after a day of archery in the course of which she presented the Surrey Bowmen with a silver arrow as a prize for a competition.

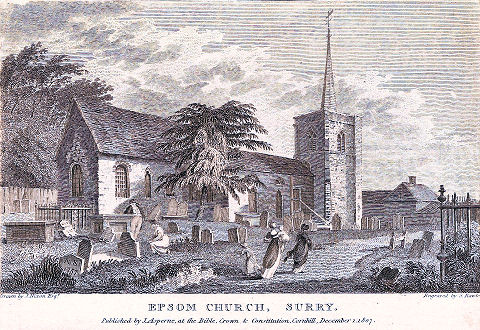

St Martin’s Church 1807

Drawn by J Nixon, Engraved by S Rawle

Image courtesy of Surrey Libraries and is held in the

Epsom & Ewell Local And Family History Centre. Image courtesy Epsom and Ewell History Explorer website

On 19 September 1791 Mrs Crespigny met Mariana in town. Although she makes no entry in clear script, surely both she and Mariana were in attendance three days later at St Martin’s Church in Epsom when, on 22 September, Millecent Parkhurst married the Rev Thomas? The Rev Jonathan Boucher conducted the ceremony and the witnesses were Millecent’s father, John Parkhurst, and her half-sister, Susanna Altham. I note that in the entry in the parish register the Rev Joseph Thomas is described as ‘of Camberwell’ – which may explain why he was discussing wedding plans in Grove House a few months earlier. I mention that Mrs Crespigny made no entry in clear script because large sections of her diary are written in shorthand and I haven’t checked whether there is such any such passage for that date.

Mrs Crespigny saw Mariana on several occasions in October. On 17th she slept at Hylands House after attending an archery match at Epsom and on the 22nd Mrs Starke, Mariana and Louisa arrived at Grove House for a short visit.

However, the atmosphere over these few days seems to have been less than calm. On 23rd October Mariana and Mary Crespigny had words -though quite what it was about is difficult now to ascertain. The diary entry appears to read ‘Miss S was very unkind to me relative to the grog and the Bow – and said things that hurt me. I was very ill in consequence.’

The following day, Monday 24 October, Mrs Crespigny records that she ‘Had a sad day with the distress of Mr Browning & Miss Louisa’ This may, perhaps, be explained by the next-day’s entry – ‘Wednesday 25 October Mr & Mrs Starke & Misses Starke & Scott, who I parted with to oblige them, set off for Nice.

”Scott’ was a woman, a maid or nurse, who until now had been in Mrs Crespigny’s employ and to whom, on her departure with the Starkes, she gave a guinea. That the Starke family was setting out for the south of France late in the autumn and despite the state of turmoil in that country would indicate that the state of health of Louisa Starke certainly – and probably also both her mother and father – had become increasingly critical. All were suffering from tuberculosis.

As early as 1779/1780 Mrs Starke, discussing her ill-health in a letter to Mrs William Hayley, had commented that ‘an hour’s talking would produce a spitting of blood’. In an April 1781 letter to William Hayley Mariana mentioned that they had been staying at Brighthelmstone for the previous two months on account of her mother’s health. The sea air was, of course, considered efficacious for pulmonary complaints. In a letter of 1787 or 1788 Mrs Starke mentioned that she and Louisa had spent a few weeks at Brighthelmstone, leaving her husband and Mariana at Hylands House.

In the Introduction to the 1815 edition of Letters from Italy (which is the one I have to hand) Mariana writes that she hopes the work will be of use ‘to those of my compatriots who, in consequence of pulmonary complaints, are compelled to exchange their native soil for the renovating sun of Italy’ and mentions that her observations on health are ‘the result of seven years’ experience; during which period my time and thoughts were chiefly occupied by endeavours to mitigate the sufferings of those most dear to me.’ Alas, little of the time abroad was devoted to nursing her sister Louisa, who, aged just 20, died at Nice on 18 April 1792, barely six months after leaving England. Had Mrs Crespigny’s comment on 24 October 1791 about ‘the distress of Mr Browning and Miss Louisa’ been a comment on a romance thwarted by her illness?

Having buried Louisa in Nice the Starke party – which Mariana describes in Letters from Italy as four in number (comprising, presumably, herself, her mother and father and ‘Scott’)- set out for Italy. In Letter 1, dated Nice, September 1792, Mariana writes that they undertook the journey over the Alps to Turin at the end of May.

On 3 November 1791 Mrs de Crespigny had noted in her diary that Mr and Mrs Starke and party had arrived at Calais and on 3 December that she had received ‘letters from Lyons’. Were those from Mariana?

I wondered briefly if Mrs Crespigny could have been the recipient of the originals of the Letters on which Mariana eventually based her book? It is the kind of role a close friend and patroness might fulfil but I must swiftly state that I have seen no evidence whatsoever to suggest that this was so. Indeed, perhaps rather surprisingly, I have come across no mention of Mrs Crespigny in any of Mariana’s manuscript letters that I have read.

The dedication in the 1815 edition of Letters from Italy is to Millecent Thomas ‘as a small testimony of gratitude for her great kindness in having corrected the press, and aided, by her deep and extensive classical knowledge, the labours of The Author’. Mariana would surely have acknowledged any specific interest taken in her work by the woman to whom she had made such a fulsome dedication in The Poor Soldier.

However, it is Mrs Crespigny we must thank (or at least those of us who follow the life of Mariana Starke in intimate detail must thank) for alerting us to the exact date when the Starkes’ coach swept out of the gates of Hylands House, taking Mariana to Italy and her destiny.

Copyright

Mariana Starke: First Productions

Posted by womanandhersphere in Mariana Starke on January 7, 2013

In 1787 J. Walter, a London publisher/bookseller operating from premises close to Charing Cross, issued – as Theatre of Education – a new English translation of Le Théâtre á l’usage des jeunes personnes, a collection of comedies by Mme de Genlis, the first woman to be appointed tutor to princes of France.

Madame de Genlis

Madame de GenlisThis innovative method of providing a moral education for children through the use of short plays had proved immensely popular on both sides of the Channel. First published in France in July 1779, an English translation, under the imprint of T. Cadell and P. Elmsly ; T. Durham, appeared in 4 octavo volumes in 1781, with a new edition, in 3 volumes, under the same imprint, following in 1783. [See http://archive.org/details/theatreeducatio07genlgoog for the online edition of the 1781 4-volume edition]. Nowhere is the name of the translator of this edition stated, although it is thought that he was male. As far as I know he has never been identified – although this really is not my field and I would welcome correction.

Nor, indeed, is there any indication on the title page of the J. Walter edition of the names of the translator(s) of his edition. It was not until 1831, when an obituary of Mrs Millecent Thomas (the former Millecent Parkhurst -see Mariana Starke: An Epsom Education) appeared, that the truth was revealed.

As the Annual Register and The Gentleman’s Magazine reported, Mrs Thomas ‘assisted her friend Miss Starke in translating Mme de Genlis’ Theatre of Education’. Over 150 years later, in Notes and Queries (45:1; March 1998), Edward W. Pitcher identified the edition translated by Mariana and Millecent as that published by J. Walter. The Annual Register had cited the translation as being issued between 1783 and 1788 in three duodecimo volumes, although a consultation of COPAC reveals no J. Walter edition pre-dating 1787. It does, however, seem to have been issued in a variety of formats. The 3-volume British Library set appears to be inscribed, if I have deciphered the handwriting correctly, ‘Miss M.B. Woollery, the gift of her friend Mrs Thomas’. Millicent Parkhurst married the Rev Joseph Thomas in 1791, the gift, if it really was from her, presumably post-dating her marriage. The only advertisement for the J. Walter edition that I have found appears in The Times, 28 July 1790, and refers to a set of four-volumes, at the not inconsiderable price of 10 shillings. J. Walter was the publisher of, among a wide variety of productions, Mrs Chapone’s works – including Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, a seminal conduct book for young women of the period. He had presumably thought it worth backing a translation of Theatre of Education to rival that issued by Cadell et al, although doubtless he had paid little to the youthful translators. It does not appear to have merited either a reissue or a second edition.

So we find that the two young women, still in their mid-20s, living close to each other in Epsom, had embarked on a new translation of a much-fêted work which they had then succeeded in getting published. Not that this, when we know their circumstances, is particularly surprising. For, by the 1780s, Millecent Parkhurst and Mariana Starke were well-educated young women, with influential literary contacts. We have noted that John Parkhurst, Millecent’s father, and William Hayley, to whom Mariana was a ‘poetic daughter’, both gave encouragement.

Mariana Starke was also on intimate authorly terms with George Monck Berkeley (1763-93), a precocious literary talent. In a letter written to him at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, on 22 August 1787, Mariana reveals ‘that I am now much better qualified to write a Tragedy than when I composed the first three Acts of Ethelinda, as I have lately studied dramatic composition with great diligence.’ She is referring to a play, Ethelinda, which she and Monck were writing together. It is tempting to conclude that her reference to recent dramatic composition might not be unrelated to the work involved in producing the translation of Mme de Genlis’ plays. A few sentences later she tells Monck that ‘After I had finished Ethelinda to the best of my abilities, I carried it to my excellent Friend, Mr Parkhurst, whose almost paternal regard for me prompted him to consider it with great attention: he has corrected all the errors which happened to strike him; and advises me to let every material thing stand as it is now, saying, he thinks the Play very dramatic, and very likely to be well received: As he has condescended to take infinite pains with the Piece, I am sure you must agree with me in thinking it would be extremely indelicate to put any Critic over him, especially as Mr Parkhurst (from the soundness of his judgment and the depth and universality of his knowledge), is perhaps of all men in this Kingdom, best qualified for the office of a Critic. I have, in conformity to your advice, shortened my own acts and lengthened yours; and I have studied to insert the many excellent speeches, with which your acts abound; but sorry am I to say, that there is one sweet speech on fame, which I know not how to introduce according to the present plan of the Play. Your speech on murder, which is, by the by, the finest thing I ever read, I have put into the beginning of the Play, where it shows to great advantage; and many more of your lines I have occasionally introduced among my own, by way of giving a strength to my composition, which it seemed to want. I find, from Joinville, that the Crusaders always crowned their Heroes with palm, therefore I have substituted that for laurel. I am told by a Gentleman who is deeply read in the records, that even Kings, in the time of Richard the 1st, did not espouse what we now call the regal style; therefore I should think Ethel had better not do it – and I have taken the liberty to alter the two last lines of Bertram’s [?] dying speech, because (if Homer may be credited) no man, who dies of a wound in the breast, can see objects immediately before his death. I have applied to a Friend for Mrs Siddons’s interest but am not certain how I shall succeed – if I was more intimate with Mrs Soane [?] I would certainly write to her; but slight as our acquaintance is, it would be too presumptuous – from you, perhaps, she might receive an application graciously. Another Friend of mine, who is acquainted with Linley and King, has undertaken to introduce Ethelinda and me to both of them, and I almost daily expect a summons to appear before those mighty Rulers of the Theatre. So, if you have any interest, work it now, let me entreat you. Linley, at present, is at Bath, but he will speedily return to London.’

Thus, it is clear that by 1787 Mariana Starke was working her apprenticeship as a playwright and knew how to network the theatrical scene. (Mrs Siddons was the most famous tragic actress of her day; Thomas Linley and Thomas King were both involved with the management of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.) It is virtually certain (although I have not yet found any pre-1788 evidence) that Mariana was already well acquainted with Mrs Mary Crespigny (see Mariana Starke: The Mystery of the Bodleian Diary), who organized dramatic performances at a private theatre erected in the grounds of her Camberwell home. The success of The Theatre of Education was predicated on the willingness of families, such as the Crespignys, to stage short plays for amusement – and instruction. For an interesting article on the relationship at this time between private theatricals and public theatre see here.

Although the translators of the J. Walter edition are not named, the ‘Advertisement’ that prefaces the text at least makes clear that they were women. ‘The fame acquired by Madame de Genlis is so deservedly great, and the Theatre d’Education so universally considered as her chef-d’oeuvre, that it naturally becomes the study and admiration of her sex; some of whom, in order to amuse their minds, and at the same time amend their hearts, by imprinting on the memory such exalted precepts as those contained in the Theatre d’Education, undertook to translate it into English, and have now, to the best of their abilities, finished this Work, which they presume to place before the eyes of an indulgent Publick….[so that].people of all ages and all ranks may derive from the Original of Madame de Genlis, the most useful and persuasive lessons, couched in the most eloquent and characteristic language.

I have only compared the two editions in the most superficial way, but, even so, could immediately detect distinct differences in the language used. It was presumably because they felt something wanting in the 1781 translation of Mme de Genlis’ work that the two young women felt encouraged to embark on their own. However, The Critical Review, while conceding that there were faults in the 1781 edition, could not bring itself to praise the J. Walter edition.

The translators make clear in the Preface to the J. Walter edition that they had sought Mme de Genlis’ permission to publish their translation of her work: ‘Permit us, Madam, thus publickly to return our most thankful acknowledgements for the honour you confer upon us, by allowing the following translation to be inscribed to your name; an honour which demands our gratitude in an especial manner, as we do not enjoy the happiness of your personal acquaintance’. There had, presumably, been an exchange of letters between Epsom and France. Unfortunately there is no correspondence (or, at least, none that I have found) that throws any more light on either the production of the translation of the Theatre of Education or its afterlife as it related to the life of Mariana Starke. I have come across no reference at all to the work in any subsequent correspondence. This is perhaps just a little surprising.

We do know, however, the fate of the other work mentioned with which Mariana was involved – for, on 30 October 1788 [at least, I think it was 1788, but it may have been 1787 – the dating of the letters is uncertain], her mother, Mary Starke, wrote from Epsom to George Monck Berkeley a letter in which she she mentions that Mariana is awaiting ‘something decisive respecting the fate of the rash, yet beauteous Ethelinda.. You long ago were informed that this heroic Damsel was presented to, and rejected, by the respective Managers of Drury Lane and Covent Garden. Her next application was to Mr Colman [of the Theatre Royal, Haymarket] who paused a long while upon the question, her merit making a deeper impression upon his mind, than upon either of the other Gentlemen. Yesterday, and not before, his determination reached Epsom – ‘That he thinks the piece distinguished by many touches of Poetry, tho’ on the whole too romantick ..for the Theatre. ‘…The dear Authoress has laid aside her pen, and taken up her distaff, in other words, her time now is chiefly occupied in inquiring as to the practicability and possibility [?] of establishing Sunday Schools & Schools of Industry in this neighbourhood. How much more becoming in a Female [?] is this than dabbling in ink. However I have derived so large a portion of amusement, not to say instruction, from some female Writers of the present age that I cannot subscribe implicitly to this opinion, worthless perhaps it does not seem proper and may so claim an exception from this lordly privilege on behalf of my own daughter. Therefore she, as I told you before, is resuming the primitive employment of the distaff. Let her rejoice at the success attendant upon the fair Heloise….’

The latter remark may refer to Monck Berkeley’s Heloise: or the Siege of Rhodes, published in 1788. Ethelinda, clearly a play set at the time of the Crusades, does not alas, appear ever to have been staged. However we know that Mariana Starke certainly did not take up the distaff and devote herself to ‘Sunday Schools & Schools of Industry’ but, if the dating of her mother’s letter is correct, had already, on 8 August 1788, seen another of her plays – The Sword of Peace – given its first public performance at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. George Colman had, as we shall discover in the next Mariana Starke post, proved most supportive.

The latter remark may refer to Monck Berkeley’s Heloise: or the Siege of Rhodes, published in 1788. Ethelinda, clearly a play set at the time of the Crusades, does not alas, appear ever to have been staged. However we know that Mariana Starke certainly did not take up the distaff and devote herself to ‘Sunday Schools & Schools of Industry’ but, if the dating of her mother’s letter is correct, had already, on 8 August 1788, seen another of her plays – The Sword of Peace – given its first public performance at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. George Colman had, as we shall discover in the next Mariana Starke post, proved most supportive.

Sources: Berkeley mss, British Library

Copyright