Archive for category Women Artists

One Artist – ‘Mary Katherine Constance Lloyd’ – Dismembered To Create Two: or The Importance Of Biography

Posted by womanandhersphere in Women Artists on February 6, 2023

Still Life by M.C. Lloyd (Constance Lloyd). (Private collection, courtesy of Napier Collyns)

Reading Rebecca Birrell’s This Dark Country: women artists, still life and intimacy in the early 20th c, I had sped through the Introduction and the first three chapters – on [Dora] Carrington, Edna [Waugh], and Ethel [Sands] – when I came to the fourth, titled ‘Mary’. The opening paragraph was intriguing, for it revealed that this artist – ‘Mary’ -was something of a mystery to the author. Birrell writes that:

‘at first she was a confusion of names, an inconsistency that asked to be resolved: she was Constance, and she was Miss Lloyd, and she was Mary, and she was Katherine – shadows with a similar shape, an address in common, a hand worn by the same work. Then she was those four strands of herself combined, she was Mary Katherine Constance Lloyd, a figure with a question hanging over her…Mary became all the small details I gathered from what she allowed me to see.’

This elusive ‘Mary’ attracted my attention. For, while Birrell employs what is known to academics as the ‘emotional’ or ‘affective’ turn to the study of these women artists, I am very much attached to the ‘biographical’ turn.Who was ‘Mary’? Why was there a confusion of names?

Googling ‘Mary Katherine Constance Lloyd’ led me to the ArtUK page for ‘Mary Katharine [sic] Constance Lloyd’, which included birth and death dates and a short biography[i]. It was then only the work of a moment to discover on Ancestry that the woman with the given dates was not a Mary Katherine Constance Lloyd but a Katharine Constance Lloyd. How peculiar, I thought, and looked again at the ArtUK page. It then seemed obvious that the paintings displayed were unlikely to all be by the same hand. Four, including the one described by Birrell in the chapter on ‘Mary’, might be classed as ‘impressionist’, while the others were formal portraits of worthy 20th-century gentlemen, attired in various robes of office.

A little more online research established that there was, indeed, another artist with a similar name, Mary Constance Lloyd, and that a succession of art reference works had carelessly blended their two lives together – to create ’Mary Katharine Constance Lloyd’. I suppose it is a measure of how little importance is attached to the lives of such women artists that in 50 years no author had bothered to research either subject ab initio – but, when compiling a new biographical dictionary or making a footnote reference, had merely copied the – incorrect – information.

Anyway, suffice to say, having now resurrected as best I can the long, professionally active lives of both women, the resulting biographies can be found below. The artist to whom Birrell devotes the ‘Mary’ chapter is Mary Constance Lloyd who, while signing her paintings ‘M.C. Lloyd’, was always known as ‘Constance’ rather than ‘Mary’. Katharine Constance Lloyd has yet, I think, to attract any authorial attention.

I must confess that I find myself rushing to Constance Lloyd’s defence, for Birrell, while establishing no firm facts about her life, yet ‘reads’ one still life to suggest that ‘Mary’s preferences tended towards invisibility, ignored proposals, anonymous works, little self promotion’.[ii]

My research into the life actually led by Constance Lloyd indicates that this was definitely not the case. I do not know what Birrell means by ‘ignored proposals’ (the phrase is not referenced), but Constance Lloyd’s work was not anonymous and the evidence is that she was not at all averse to self-promotion, taking part in numerous exhibitions, her work cited in reviews, happy to accept the help offered by her old friend Duncan Grant in getting her work shown and, even in old age, keen to engage in interviews with the press.

On one specific point Birrell is incorrect in stating that ‘she lived in Paris from the turn of the century to the twenties, after that she returned to England, and life was different, quieter. Long walks, rooms lit weakly by the fire, an ache in the hands once her letters were finished, slipping under heavy bedding before it grew dark’. Birrell gives no reference for the described scenario, but Constance did not, in the 1920s, return to live in England. Indeed, in her will, drawn up in 1958, she specifically states that she had lived in France since 1908. She died in Paris 10 years later.

Finally, Birrell states, ‘What happened to her practice is unclear.’ My short biographical study answers that question. Constance Lloyd was exhibiting in London when she was 79 years old – and continued painting for the rest of her life. Family members fondly remember her as engaging and spiritedly independent, recalling visits to her crowded Parisian flat and to her house at Genainville, their memories ranging from her love of Siamese cats and Black Magic chocolates to her fluent French, spoken with a ‘Churchillian accent.’

Although I do understand that in This Dark Country Birrell is applying ‘a loose and interpretive method’ to her study of her chosen artists, she does not rely solely on the ‘emotional turn’ when discussing artists such as Carrington and Vanessa Bell, but also draws from the wide range of available biographical detail. It does seem a pity, therefore, that, by resisting any attempt to discover who ‘Mary’ really was, Birrell allowed her ‘to slip away unnoticed’, suggesting that ‘There was a freedom in existing as she did, as a series of charged impressions, connected only to a handful of letters, sometimes as Mary and sometimes as Constance, no husband or acquired surname to place her firmly within an established familial structure.’ I am not sure that ignorance should be equated with freedom. Great-Aunt Con is still very much a reality to the Lloyd family (a familial structure in which she was firmly established) who would, I am sure, have been as happy to share their knowledge of her life and work with Birrell as they have been with me.

Mary Constance Lloyd

The Lloyd family photographed outside ‘Farm’, c. 1900. Constance is standing 4th from left. (Courtesy of Sampson Lloyd)

Lloyd, Mary Constance (7 October 1873-1 August 1968) was born at the Lloyd family home, ‘Farm’, Sampson Road, Sparkbrook, Warwickshire, the youngest of the twelve children (ten daughters and two sons) of Samuel (1827-1918) and Jane Lloyd (1839-95). While ‘Mary’ was her first given name – and she signed her paintings as ‘M.C. Lloyd’ – she was always known as ‘Constance’ and, within the family, as ‘Con’.

Constance’s family was wealthy. Her great- great-grandfather had been the founder of Lloyds Bank; her father was a steel maker, an ‘iron master’. Neither she nor her sisters were compelled to earn their own living, although several of them carved out distinctive careers. Adelaide (1861-1937) trained as a nurse, became matron of Stratford-on-Avon Hospital and then, from 1895 for ten years, matron of Birmingham Children’s Hospital. In 1914 she was elected, by an overwhelming majority, a member of Sparkbrook board of guardians.[iii] [Margaret] Jessie (1865-1952) was in 1911 secretary of Birmingham Infants’ Health Society and treasurer of the Adult School Union.[iv] Julia (1867-1955) trained as a teacher at the Froebel institutes in Edgbaston and Berlin and was for some time an instructor in a St John’s Wood, London, training school for kindergarten teachers. She then returned to Birmingham, where she set up kindergartens in poor districts and was secretary of the Birmingham People’s Kindergarten Association, which became, in 1917, the Birmingham Nursery Schools Association.[v] Another sister, Edyth (1860-1936), was also involved in welfare work, in 1915 working for the Ladies’ Association for the Care of Friendless Girls and, alongside Julia in Birmingham Women’s Settlement.[vi] Being independently wealthy the sisters had no need to find financial support through marriage and only one, Caroline (1863-1921), chose to marry. Gwen John exaggerated only slightly when she reported to Rodin that Constance Lloyd had nine sisters, all above the age of 23, none of whom had ever had a lover.[vii]

Little is known of the sisters’ education, although in 1881 two of Constance’s older sisters, Caroline and Jessie, were pupils at St John’s Ladies’ School in Patcham, Sussex, while in that year Julia began attending Edgbaston High School. It is likely that Constance, who, living at home aged 17, is described as a ‘scholar’ in the 1891 census, was also a pupil at Edgbaston High. In that census two other of her sisters, Edyth and Marian, were noted as being science students and staying with the family on census night was Mildred Pope, later an eminent scholar of Anglo-Norman England, then a student at Somerville College, Oxford.[viii] Alas, when encountered in the next census, in 1901, Marian had entered Barnwood House, a private Gloucestershire mental hospital, where she was to remain for the rest of her life.[ix]

From October 1896 until July 1897 Constance was a student at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, studying under sardonic and sarcastic Henry Tonks. Her mother had died in March 1895, which might have been a signal for release from home, or may, of course, have been entirely coincidental. There certainly was no shortage of daughters to fulfil the role of ‘daughter-at-home’. Constance was an assiduous attender at the Slade, signing in most days, alongside such fellow students as Gwen John, Maude [Grilda] Leigh-Boughton, and Edna Waugh. However, she only spent one year at the Slade, apparently disappointed by the experience; Tonks ‘had no conception of her abilities.’[x]

It is not known whether she continued her studies elsewhere during the following three years before, in 1901, we find her taking lessons from Simon Bussy, who had come from France and rented a Kensington studio.[xi] Among her fellow pupils was Dorothy Strachey, who married Bussy in 1903. Constance became a ‘lasting friend of the Bussy family’.[xii] In 1903 she was painting in Venice[xiii] and by 1904, ‘under the weight of parental disapproval’,[xiv] was living in Paris, studying at the Académie Colarossi and sharing an apartment at 118 rue d’Assas, a tall building close to the Luxembourg Gardens, with Aline Baylay.[xv]

Gwen John, with whom Constance had maintained a close friendship since her Slade days,[xvi] was a fellow-student at the Colarossi – and also living in Paris with his family was her brother, Augustus. We catch a glimpse of Constance – described as ‘nice and awkward and ugly’ – in a letter written to him by his wife, Ida.[xvii] Family information reveals that Constance was born with a deformity of the foot, which may account for the description of her as awkward. Constance Lloyd may have used Gwen John as a model on a number of occasions. One nude study, now in held by the National Library of Wales, is thought to date from 1905 and it is possible she also painted her in the summer of 1907.[xviii]

By now Constance was also friendly with Duncan Grant, whose address she had been given by his cousin, Pippa Strachey (sister of Dorothy Bussy), and spent time with him copying in the Louvre.[xix] Her circle of friendship also included Eileen Gray, Paul Henry, and Stephen Haweis. In the summer of 1908 five of her paintings were included in the Allied Artists’ Association exhibition[xx] at the Albert Hall in London and in February 1912 her work was shown by the Friday Club at London’s Alpine Club, alongside that of Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell, and Gwen Raverat.[xxi] Of her painting the Times reported, ‘The little landscape and still lives of Miss Constance Lloyd show professional skill, but they have an amateur simplicity and would be charming ornaments to a small room. The same artist shows some cretonnes which carry on the Morris tradition with feminine originality’.[xxii]

For Constance Lloyd did not confine herself to fine art, but c. 1910 was among the artists commissioned to produce designs for a Parisian company run by Andre Groult. Her designs do not survive, but Groult’s patterns were said to be ‘Modern in spirit, although moderate in tone’, ranging from stencil-like, flat stylised flower and fruit patterns to Dufyesque narrative toiles.’[xxiii] In 1914 Constance designed a night nursery, her furniture design executed by Damon & Bertaux, a very reputable firm of cabinet makers.

After returning to England on the outbreak of the First World War, Constance later went back to France, moving between Paris and the countryside and, in 1918, in a letter home, described the shelling of Paris. By 1919 she was living in a flat in the 4th arrondissement with a view of the Seine, high above the Boulevard Henri IV.[xxv] This view was remarked upon by Gwen John who also had returned and who, in 1921 gave Constance, to give to her sisters for Christmas, some sketches she had made of women in the congregation of the church in Meudon.[xxvi]

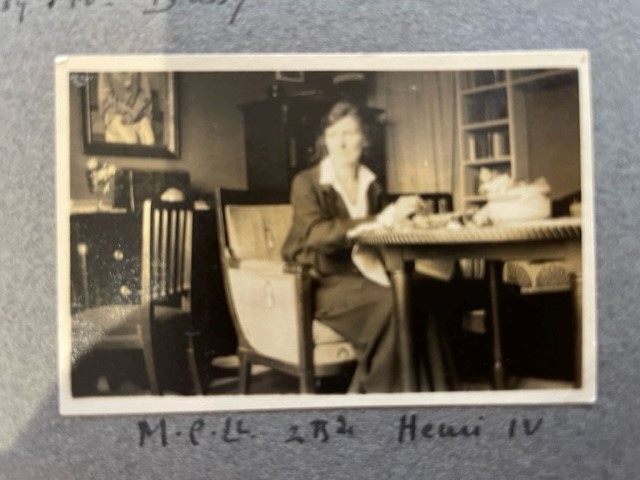

Constance Lloyd in her Parisian flat, 1924. (Courtesy Collyns family)

Constance and Gwen continued to live in Paris, in 1930 attending classes given by the influential artist and teacher, André Lhote.,[xxvii] and remained friends until Gwen’s death in 1939.[xxviii] In the mid-1920s Constance Lloyd was a supporter of Shakespeare & Co, Sylvia Beach’s renowned bookshop, but, alas, no record survives of any book borrowing.[xxix]

Constance Lloyd at her cottage in Genainville, 1924. (Courtesy Collyns Family)

In the early 1920s she bought a cottage at Genainville, a village 50 km north of Paris, owning it for the rest of her life, beloved by her neighbours and often visited there by members of her family. In 1931 Duncan Grant recommended the cottage to David Garnett who, with his wife Ray and young sons, was proposing to winter in France. In fact, it was almost by accident that the Garnetts did, indeed, end up renting Constance’s house for three months and, in the event, were less than enamoured with the village – ‘It is very cold and damp – and the sun never shines – and it is much more difficult to get into Paris than I had expected’.[xxx]

During this period Constance moved to an apartment in 8 avenue de Breteuil[xxxi] in the 7th arrondissement, close to Les Invalides and the Eiffel Tower, and was in Paris in 1940 when the Germans invaded, writing home a detailed description of life in the city and surrounding countryside.

‘..a large car full of German officers, and a loud speaker, have gone slowly by telling us not to stir out of doors again till seven o’clock tomorrow morning….My studio is lovely in the summer sunshine, and the trees opposite so green and full of shadow – the avenue empty most of the time, such peace and quiet.. ..5 July. I took the metro which is working (there are no buses and no taxis) to the Madeleine, and then sat at a cafe nearly opposite Lloyds Bank, and had some very good strong coffee with 3 lumps of sugar, and a sympathetic waiter. Lloyds Bank, as I could see from where I sat, is open, but has become a German Bank…I saw nothing was possible at the Bank...’[xxxii] This letter was posted for her in Lisbon by an American friend, Virginia Hall, who had been an army ambulance driver in France but, after the German invasion, made her way to Spain. She was soon to be recruited by SOE, returning to France as an agent in 1941.

Towards the end of the war Constance was able to return to England for a visit and, interviewed by The Birmingham Mail, recounted how she was arrested by Germans in her Parisian flat on 5 December 1940 and taken to Vauban Barracks, Besancon, where 5000 other women with British passports were housed.

‘They came for me at 7.15 in the morning, and unfortunately did not tell me that I was being taken to an internment camp. Consequently, I had only a rug, a piece of chocolate, and two pairs of spectacles.[We] were quartered in barracks quite suitable for young soldiers, but quite unsuitable for elderly ladies….At first we slept on dirty mattresses on the barrack floor and we had to forage for broken plates and utensils from a scrap heap to use. Many of the internees became ill because of the severe conditions and the bad and meagre food, and between 400 and 500 of them died in a period of six months’.[xxxiii] Constance was released early in 1941, and allowed to return to her flat in Paris, although relieved of her wireless set and telephone.

In the immediate post-war period Constance’s long-time friendships bore fruit; apparently it was Duncan Grant who was instrumental in organising for her a joint exhibition with Janie Bussy (daughter of Simon and Dorothy Bussy) in 1947 at the Adams Gallery in London.[xxxiv] Of Constance’s paintings the Times critic wrote, ‘Her subjects one feels have been chosen with the greatest care and forethought, not only to suit a natural refinement of taste – the taste perhaps of a fastidious Englishwoman who likes everything to look French – but also because they are precisely adapted to the decorous originality of her colour and the sagacious simplicity of her design. …the work of an experienced artist with a real feeling for quality of paint who has understood and quietly developed her individual sensibility’[xxxv]

Still life by M.C. Lloyd (Constance Lloyd). (Courtesy Freston Family)

Five years later, in October 1952, now nearly 80 years old, she once again exhibited at the Adams Gallery. The Bloomsbury Group again rallied round; Quentin Bell reviewed the exhibition in The Listener, remarking ‘her only claim to fame rests upon the fact that she paints exceedingly good pictures. Her great talent lies in finding perfect juxtapositions of colour, of building – with beautiful economy and consummate art – a pattern of closely related tones, so finely balanced that, although her drawing is not remarkable, she creates a completely convincing world of light and space.‘[xxxvi] Another critic suggested that she ‘belongs, it seems, to the school of painting of Vuillard and Bonnard,’[xxxvii] while another remarked that the exhibition was ‘notable for paintings done in Paris and Venice, most of them still-life. They are of exceptional merit.’ She told the journalist that she would be leaving London for the sunshine of the West Indies – ‘That’s necessary for me because of my age and my desire to go on painting.’[xxxviii] In fact she set sail on 29 November to stay in Dominica with Stephen Haweis, another friend from her earliest days in Paris.[xxxix]

Constance Lloyd photographed with a nephew in her Parisian flat, 1968. (Courtesy of Sampson Lloyd)

Constance Lloyd lived another 16 years, dying in her apartment in Paris. In her will she had instructed that, in this eventuality, she should be cremated, and her ashes deposited at the cemetery at Genainville.

Of her paintings in public collections, one is the nude study of Gwen John mentioned above, one, the still life critiqued by Rebecca Birrell, is held at Charleston House, home of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, apparently given to the Charleston Trust, though I’ve been unable to find out by whom.[xl] The other two, one a landscape and one a still life, both rather indistinct, are held in Chastleton House, now owned by the National Trust but once the home of Alec Clutton-Brock, an art critic. It is likely that the paintings are in the house because Constance knew either him or his father, who had been art critic of the Times and who, in 1909, had given ‘books’ as a wedding present to Aline Baylay and Albert Lloyd. Other of Constance Lloyd’s paintings are held by members of her family.

Katharine Constance Lloyd

Lloyd, Katharine Constance (10 November 1884-18 October 1974) was born at Hartley Wintney, Hampshire, the third child, and eldest daughter, of the eight children (five sons and three daughters) of Edward Wynell Mayhow Lloyd and his wife Eleanor (née Hastings). Her father, a renowned cricketer, educated at Rugby School and Cambridge University, was, from 1876 until 1910, the owner and headmaster of Hartford House, a boys’ preparatory school in Hartley Wintney. Four of Katharine’s brothers were educated at Rugby, where her uncle (Charles Hastings, her mother’s brother) was a master, but there is no information as to where she and her sisters went to school. Nor is it known if – and, if so, where – she attended an art school, although it is very likely that she did.

After her birth, the first public record found for Katharine Lloyd dates from 1906 when, on 18 August, she set sail for Cape Town, South Africa. She was doubtless journeying to stay with her brother Arthur (1883-1967) who, after graduating from Oxford, had, in 1905, left for South Africa, remaining there for five years while working as a cartoonist for the Rand Mail and Johannesburg Star. In the 1911 census Katharine is living at home in Hartley Wintney with her two younger sister – and five servants – head of the household in her parents’ absence.

Katharine Lloyd next appears in the public records, described as ‘Artist (Painter)’, in the 1921 census, living at 20 St Thomas Mansions, Stangate, Southwark. Her brother Arthur, who had been injured while serving in South Africa during the First World War, was on the census night at the family home in Hartley Wintney but gave his permanent address as that of the Southwark flat. Arthur is described as a ‘Black & White Artist’, working for Bradbury, Agnew & Co, proprietors of Punch. For many years Katharine Lloyd lived at addresses in Redcliffe Road, Fulham.

We first find evidence of Katharine Lloyd’s work as an artist in 1921 when a portrait, after Hoppner, of Lieutenant-General Sir Ralph Abercromby, an 18th-c Old Rugbeian, was commissioned from her by Rugby School.[xli] In fact, her connection to Rugby resulted in a number of similar commissions, including a portrait of other former pupils; one of Lewis Carroll, copied from the original by Herkomer that hangs in Christ Church, Oxford, [xlii] one of William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury,[xliii] one of Hugh Lyon, headmaster of Rugby, 1931-48, and one of Sir Pelham Warner, president of the MCC.[xliv] The Warner portrait was a copy of one commissioned from Katharine Lloyd in 1949 by the MCC to hang in the pavilion at Lord’s Cricket Ground. For the pavilion she was also asked to copy the 1768 painting by Francis Cotes of ‘The Young Cricketer: Portrait of Lewis Cage’. This remained at Lord’s until 2008, but, after the MCC was able to purchase the original, in 2020 Katharine Lloyd’s copy was sold at auction, realising £13,000.

It is obvious that Katharine Lloyd’s association with Rugby School was important in effecting commissions, but other family connections also helped to raise her artistic profile. In 1936 the Royal Academy exhibition included her portrait of the ‘Rt Hon and Rt Rev the Lord Bishop of London’ who, as Arthur Winnington-Ingram, had been a pupil at Hartford House School when Katharine’s father was headmaster. The following year, 1937, Katharine Lloyd had another portrait selected for the RA exhibition, that of ‘Anne, daughter of late Major C.L. Compton Smith’. Anne[xlv] was Katharine Lloyd’s niece and in the 1930s had lived with her at 64 Redcliffe Road, Kensington. Katharine’s posthumous portrait of Anne’s father, Major Geoffrey Compton-Smith, who was murdered by the IRA in 1921, while serving in Ireland, is held by the Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum. The 1943 RA exhibition included another of Katharine’s portraits of a family member – ‘His Hon Lord Gamon’, her brother-in-law, Hugh R.P. Gamon.[xlvi]

In 1948 Katharine Lloyd was commissioned to paint the portrait of Dr J.W. Skinner, retiring headmaster of Culford School, Bury St Edmunds. The fact that he was depicted holding a copy of Punch caused much local merriment. The press report described the artist as ‘a Royal Academy exhibitor’,[xlvii] which may account for the commission she promptly received from Bury Town Council, who paid her a substantial sum to paint a portrait from photographs of the late Alderman Lake.[xlviii]

Katharine Lloyd made something of a speciality of posthumous portraits, commissioned as memorials to the recently departed. ArtUk references portraits of Sir William Carey, Bailiff of Guernsey[xlix] and Jan Hofmeyr, eminent South African politician,[l] both of which are likely to have been posthumous. Her posthumous portrait of Bishop Mosley, the late bishop of Southwell, was unveiled in 1949, one press report mentioning that, although a local artist would have been preferred, Miss Lloyd had been selected because she lived near to the home in the south of England to which the Bishop had retired. In the event, he died before work could start and she painted the portrait from photographs.[li]

Two other portraits by Katharine Lloyd listed on the confused ‘Mary Katherine Constance Lloyd’ ArtUK page are of Archibald Harrison and James Ross, both one-time principals of Westminster College. Harrison’s portrait was actually painted posthumously, in 1947, while Ross’s marked his retirement in 1953. In 1956 she painted what may have been her final commission, a portrait of G.H. Ash, headmaster of the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, Hartlebury, near Worcester. [lii]

Although portraits of (male) worthies probably provided Katharine Lloyd with a bread-and-butter income and she did exhibit with the Royal Society of Portrait Painters, she also painted landscapes and still lives. In 1923 she exhibited a view of Niton, Isle of Wight[liii] with the NEAC and in 1929 a view of Ventnor at the Society of Women Artists .Her RA exhibits included flower paintings, shown in 1944 and 1946.

In 1934 Katharine Lloyd held a joint exhibition with her brother Albert at the Coolings Gallery. A review in the Times (23 October 1934) mentions that she displayed a ‘wide range of subjects, from crayon portraits to landscapes in water-colours, and throughout her work there is evident a good sense of design. It is most apparent in the water-colours, in which the ‘pattern’ of the landscape is emphasized and supported by well-related tones of colour.’ Among the landscapes were, again, scenes at Niton and at Hartley Wintney.

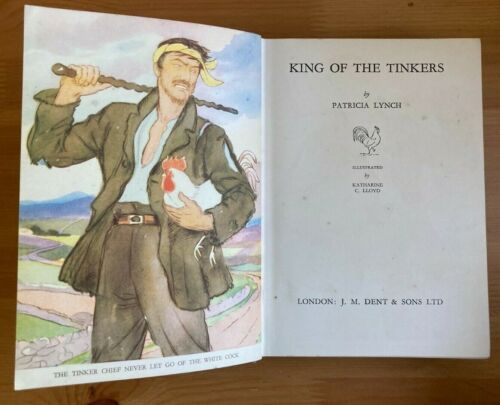

At this exhibition Katharine Lloyd also showed oil paintings of ‘Carting Turf in West Ireland’ and ‘Keel, Achill Island’. These last two may relate to a commission to illustrate Patricia Lynch’s The King of the Tinkers, published by J.M. Dent in 1938, for which she provided eight full-page colour and numerous smaller black-and-white illustrations. As far as I know she only illustrated one other book, Eleanor Doorly’s Ragamuffin King, Henry IV, King of France, published by Jonathan Cape in 1948.

Katharine Lloyd’s frontispiece for King of the Tinkers

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement

[i] The ArtUK page notes that the biographical information is sourced from D. Buckman, Artists in Britain since 1945, Sansom & Co, 2006.

[ii] The ‘Mary’ chapter is the only one in This Dark Country that is not illustrated, but the painting referred to is ‘Still Life with Fan’, held by the Charleston Trust.

[iii] Adelaide. a member of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, was backed in the 1914 election by the Association for the election of women on governing bodies and in 1919 her re-election to the board of guardians was backed by the National Union for Equal Citizenship.

[iv] I think Jessie was a nurse at Westminster Hospital in 1891 and during the First World War, as a trained masseuse, was working with the French Red Cross. However, I have not been able to prove beyond dispute that this Margaret Jessie Lloyd is ‘our’ JML.

[v] For more about Julia Lloyd see R. Watts, ‘Julia Lloyd’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[vi] See Birmingham Post, 27 February 1915, 4 and Birmingham Evening Mail, 23 June 1980, 7.

[vii] The story is reported in Roe, Gwen John: a life, Chatto & Windus, 2001, 63

[viii] I do not know where Edyth and Marian were studying, but it was not at Somerville.

[ix] It is to be remarked that Marian’s father, Samuel Lloyd, when completing the 1901 census form, wrote in the column intended for remarks as to whether any of the household were ‘Deaf and Dumb; Blind; Lunatic; Imbecile, feeble-minded’ wrote ‘None of this character in this house. S.L.’

[x] Frances Spalding, Duncan Grant, Chatto & Windus, 1997, 47.

[xi] On the night of the 1901 census Constance was staying in Warwickshire with her brother Albert. She is described as ‘Artist’.

[xii] Spalding, Duncan Grant, 47

[xiii] For instance, her paintings Riva degli Schiavoni and Santa Maria della Salute have sold in recent years. In 1904 she exhibited a painting, ‘Venice’, at the Women’s International Art Club exhibition at the Grafton Galleries. The critic from the Daily Mirror singled it out – ‘It is full of light, air, and breeze, and Miss Lloyd has had the courage to remind us that Venice has factories and chimneys, without detracting from the fresh beauty of her little picture.’ Daily Mirror, 27 Jan 1904, 2.

[xiv] Spalding, Duncan Grant, 47. Presumably if there was any disapproval it came from her father, her mother having, as we have noted, died some years earlier. It is unlikely the mere fact of living abroad caused consternation; her sister, Julia, had studied in Berlin. Perhaps it was the artistic milieu that was suspect.

[xv] In 1909 Caroline Emma Baylay (1878-1962) married Constance Lloyd’s brother, Albert. In the 1901 census Caroline’s occupation was ‘art student’.

[xvi] Roe, 48.

[xvii] Letter from Ida to Augustus John, 10 November 1906, see Roe, 80. Interestingly, Augustus had been a pupil at the Slade at the same time as Constance so presumably knew her by sight.

[xviii] The NLW painting is signed ‘M.C.Lloyd’. The donor, a family member, indicated it was painted in 1905. Roe, 91-2, mentions that Gwen modelled for Constance in 1907.

[xix] In 1909 Col and Mrs Grant gave a wedding present to Aline (Bayley) and Albert Lloyd, suggesting that there may have already been an established family connection to one or the other. Would they have given a present to a couple, one of whom was merely a friend of their son? Both Col Grant and Charles Bayley, Aline Bayley’s father, had seen service in the army in India; perhaps their paths had crossed there.

[xx] Constance Lloyd’s address is given in the catalogue as 38 rue du Montparnasse.

[xxi] See the Times, 13 February 1912, 11. The Friday Club had been founded by Vanessa Bell in 1905 but in 1913 she, with Roger Fry and Duncan Grant, broke away and established the rival Grafton Group. The first Grafton Group exhibition was held in March 1913, but, as the Times reported (20 March 1913, 4) the works were displayed anonymously, so it is impossible to know if Constance Lloyd was among their number.

[xxii] Times, 13 February 1912, 11.

[xxiii]Lesley Jackson, 20thc Pattern Design: textile and wallpaper pioneers, Mitchell Beazley, 2002, 51.

[xxiv] The Studio Yearbook of Decorative Art, 1914,145.

[xxv] Roe, 192.

[xxvi] Roe, 210.

[xxvii] Roe, 195.

[xxviii] In 1957 Constance Lloyd gave to the Tate two of Gwen John’s works that she owned – ‘Cat’ (watercolour) and ‘Annabella’ (charcoal and wash).

[xxix] See https://shakespeareandco.princeton.edu/members/lloyd-mary-constance/

[xxx] From a letter by Ray Garnett, quoted in D. Garnett, The Familiar Faces, Chatto & Windus, 1962, 123.

[xxxi] I think this was a new apartment block, built in 1933.

[xxxii] Letter from Constance Lloyd to her sister Charlotte, 29 June 1940. See https://www.sampsonlloyd.com/#/gallery/great-aunt-cons-letters-from-paris-during-world-war-two/constance-lloyd-letters-box-76116/

[xxxiii] The Birmingham Mail, 22 March 1945, 3.

[xxxiv] Spalding, Duncan Grant, 404.

[xxxv] The Times, 12 July 1947, 6.

[xxxvi] The Listener, 16 October, 1952, 644. One of Constance’s still lives, bearing an Adams Gallery label, passed through Holloway Auctions in 2019, selling for £10.

[xxxvii] Truth 17 October 1952, 405.

[xxxviii] Western Mail, 7 October 1952, 4.

[xxxix] Mentioned in Goff, Eileen Gray: her work and her world.

[xl] The Charleston Trust is unable to disclose acquisition information.

[xli] See report of Speech Day in Rugby School’s magazine, The Meteor, vol 55, issue 663, 1921.

[xlii] Mention is made of the Lewis Carroll portrait in the report of Speech Day, The Meteor, vol. 69, issue 812, 1935, although it is not clear when the painting was made.

[xliii] Painted posthumously; Temple died in 1944. I think the portrait was presented in 1946; its existence was certainly mentioned in Rugby Advertiser, 16 June 1950.

[xliv] The two last portraits were painted in 1950. See Rugby Advertiser, 20 June 1950, 3.

[xlv] Anne (later Mrs Anne Peploe) was an amateur artist – see Sevenoaks Chronicle, 4 December 1976, 4.

[xlvi] Married Katharine’s sister, Margaret Eleanor Lloyd, in 1914.

[xlvii] Bury Free Press, 9 July 1948, 6. It was intended that the presentation of Skinner’s portrait should have been made by Dr H.B. Workman, who had been the principal of Westminster College before Archibald Harrison. This suggests that Katharine Lloyd may have benefited from some Westminster College networking.

[xlviii] This portrait appears on ArtUK, held by West Suffolk Heritage Service, and dated to 1946. I think this date is incorrect and should be amended to 1950 – the portrait was unveiled in April 1950 – see Bury Free Press, 7 April 1950, 3. In the Bury Free Press (13 August 1948, 1) Katharine Lloyd’s fee is given as 200 guineas, but in a report in the same paper (12 November 1948, 16) it is cited as 100 guineas.

[xlix] He died in 1915. This is the earliest of Katharine Lloyd’s works so far found.

[l] Hofmeyr died in 1948, This commission may well have come through Arthur Lloyd.

[li] Newark Advertiser, 13 April, 1949, 1; Nottingham Evening Post, 8 January 1949, 3.

[lii] Birmingham Post, 23 April 1956, 5

[liii] She exhibited the same, or a similar, view of Niton at the Royal Academy in 1933.

NOW PUBLISHED: ART AND SUFFRAGE: A BIOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARY OF SUFFRAGE ARTISTS

Posted by womanandhersphere in Women Artists on February 1, 2018

NOW PUBLISHED

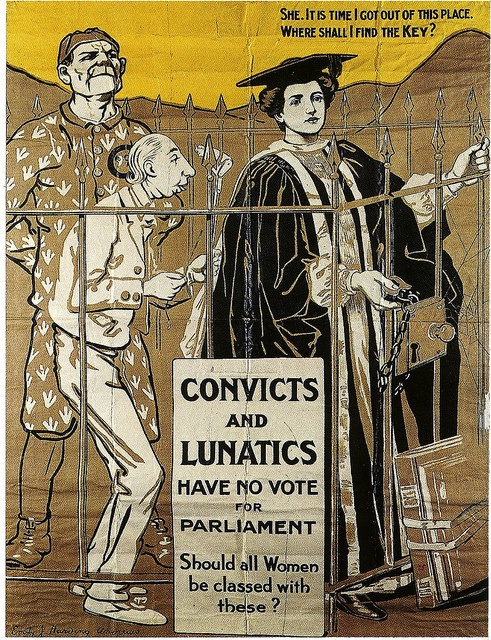

Art and Suffrage: a biographical dictionary of suffrage artists discusses the lives and work of over 100 artists, each of whom made a positive contribution to the women’s suffrage campaign. Most, but not all, the artists were women, many belonging to the two suffrage artists’ societies – the Artists’ Suffrage League and the Suffrage Atelier. Working in a variety of media –producing cartoons, posters, banners, postcards, china, and jewellery – the artists promoted the suffrage message in such a way as to make the campaign the most visual of all those conducted by contemporary pressure groups.

In the hundred plus years since it was created, the artwork of the suffrage movement has never been so widely disseminated and accessible as it is today, the designs as appealing as they were during the years before the First World War when the suffrage campaign was at its height. Yet hitherto little has been known about most of the artists who produced such popular images. Art and Suffrage remedies this lack and sets their artistic contribution to the suffrage cause within the context of their reanimated lives, giving biographical details, including addresses, together with information on where their work may be seen.

With over 100 illustrations, in black-and-white and in colour. 248pp. Soft covers £20

ISBN 978 1 9999037 3 2

Published by Francis Boutle. You can order directly from me – by emailing elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com

Or you can order through any bookshop

Women Artists: ‘Painting Days At School of Art Are Perfect Bliss’ (1892-1914)

Posted by womanandhersphere in Uncategorized, Women Artists on November 11, 2014

I originally gave this paper at the Women’s History Network Conference, Southampton, September 2005

‘Painting Days at School of Art are perfect bliss: the manuscript diary (1892-1914) of Sarah Madeleine Martineau, art student and craft worker’.

This paper is based on the manuscript diary of Sarah Madeleine Martineau, the first entry in which is for 1 January 1892 and the last for 25 January 1914. I bought the diaries a few years ago, at the time giving them merely a cursory glance and registering only that the world they depicted was one that appealed. At odd intervals I have undertaken some research into the life and work of Sarah Madeleine Martineau and now think that what the diaries reveal is of some general interest.

The Martineaus’ house at 122 King’s Avenue would have been very similar to this, no 104. (Image courtesy of Ideal Homes: A History of the South-East London Suburbs)

She was born in London at 4 South Road (later 122 King’s Avenue), Clapham Park, on 2 May 1872, the final child in the family of David Martineau, the senior partner in a firm of sugar refiners and a leading Clapham Liberal. David Martineau’s grandfather was a brother to the father of Harriet Martineau and Dr James Martineau. In 1856 David and his wife, Sarah, settled in South Road, in leafy Clapham Park. The Martineaus’ house and its immediate neighbours have been demolished, making way for tower blocks, but it was then quite new, was large, double-fronted and detached, set well back from the road, with stabling, and grounds ample enough to include a tennis court.

The Martineaus were Unitarians and with another South London family, the Nettlefolds of Streatham Grove, Norwood, were pillars of the Unitarian church in Effra Road, Brixton. The Martineau family comprised four sons and four daughters, the eldest child, Daisy, being 16 years older than Madeleine. Of the Martineaus’ sons, two married Nettlefold sisters; Unitarians tended to stick together. Although enjoying an active social life the younger Martineau daughters do not seem to have attended many formal parties or dances. Of the daughters only Daisy married; Lillie, Lucy and Lena (such were the diminutives by which they were known) probably lived together in the family home, certainly until the 1940s, and then either together, or near each other, in south London, for the rest of their long lives. At the 1891 census besides members of the immediate family there were also living in the house a cook, a parlour maid, two house maids and a 20-year old cousin, Charles Worthington. Lena possibly had a tenderesse for Charlie; she always mentions any little attention she received from him, but in 1895 he died suddenly – the relevant entry reads: ‘Charlie, the sweetest man that ever lived is dead. He died on Christmas day..’

David Martineau’s sister, Mary, who lived close by with their mother, can be spotted as a member of many of the women’s causes of the day, for instance signing the 1889 Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage. Lena Martineau and her sister Lucy, who was three years older, had been boarders at Roedean school in Sussex, which, recently founded, was much favoured by the daughters of the wealthy non-conformist middle class. When Lena begins her diary in an exercise book in January 1892 one of the first entries relates that Barbara Shore Smith, who had been a contemporary at Roedean, had come to stay and in May 1892 Lena and Lucy went to visit Barbara, then at Girton, staying in lodgings near the college. Lena must have been well aware of all the feminist causes of the day, but, although writing her diary through the years of the main suffrage activity, makes no comment whatsoever on any aspect of the woman question. It must also be mentioned that in the entire 22 years covered by the diary she only mentions one book. On 23 February 1893 she wrote, ‘Have been reading a book called ‘Mona Maclean, medical student’, & think it splendid.’

Perhaps Lena was uninterested in the written word but her free-thinking, prosperous, well-educated family set great store by art. Lucy and Lena were clearly given every encouragement to practise any aspect of art in which they were interested. Thus apart from visiting friends, playing tennis, taking what seem exceptionally long walks and bicycle rides, and helping with bazaars and garden parties, Lena seems to have been fully occupied with attending art classes and visiting galleries. There were prominent role models very close to home. The two daughters of Dr James Martineau, Gertrude and Edith, together with their sister-in-law, Clara Martineau, were all working artists, exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy and at the Dudley Gallery. Their work now sells well – a watercolour by Edith Martineau sold for over £3,500 in 2005. The Martineaus were committed visitors to art galleries. For instance in the diary’s first year, on 22 April, Lena wrote, ‘Lucy and I met Papa at the private view of the Old Water Colours. It was very hot and full, but a good many very nice pictures.’ I am afraid that Lena’s criticism of the art that she took such care to see rarely rises above this level of comment.

In her new diary on Friday 8 January 1892 Lena Martineau wrote: ‘Art School began again on Monday, but we did not go till Tues. I have a side view of the girl so shall soon have done it..’ The Art School that she and Lucy attended was Clapham Art School, in Vernon Road, Clapham High Street, which had been founded in 1885 and was associated with the Government Schools at South Kensington – students were expected to take the Government examinations. In January 1892 Lena was taking drawing and painting classes, which she very much enjoyed, writing on 3 February ‘Joy! Mr Nightingale [the headmaster] told me that I am to begin painting my next head’ and on 21 February the entry that gave this paper its title ‘Painting days at School of Art are perfect bliss!’. In May she sat exams in the Life and Antique – ‘Given the choice of faun or the discobolus, we did the latter’. In July she heard that she had passed the exams, both 2nd class.

After a summer break, some of which was spent sketching in Wales, Lena returned in October to Clapham Art School. Her entry adds, ‘Found that Miss Pemberton is working there now’.

From the context it would appear that Lena already knew Sophie Pemberton, a Canadian artist, just three years older, who had already studied in Paris at the Academie Julien. Her father was the first surveyor general for Vancouver Island and Sophie was living in Alexandra House in Kensington, which had been built to house women music and art students and to where she often invited Lena for tea. It was – and remains, though much altered – a rather glamorous hostel, replete with terracotta panels and intricate Doulton tiles and picture panels.

In May Lena took Life and Still-life exams. Of the latter she wrote ‘the group was a top hat and two oranges on green baize!. Got home in time for some tennis’. On the 29th there was the recurrence of a problem that plagued the art school, ‘I went to the Art School but finding no model returned – & had my hair cut.’ I suspect that Clapham School of Art did not meet Sophie Pemberton’s standards because she instigated a move to Westminster School of Art in Tufton Street, Dean’s Yard, where, by October, she, Lucy and Lena were enrolled. As with the Clapham School, Westminster followed the South Kensington regime. It is worth noting that Lena chose to attend such a school, where the syllabus was geared to an examination system, rather than one of the many art schools established to cater for the ‘ladies’ market.

Of Mr Loudan, the principal instructor at Westminster and a portrait and genre painter, Lena remarked ‘Very squashing, makes me scrape out but does not say much’. On 7 December she wrote ‘Today Mr Loudan was very crushing to me’. However she persevered happily, the following March reporting that ‘Our new model on Monday was a boy and on Thursday Mr Loudan praised me for better colouring and came twice to me’. That May she again sat the Life and Antique exam. All this intermingled with much gallery visiting; Venetian pictures at the New Gallery, a visit to Herkomer’s studio to see the work of some of his Bushey students (‘Very good some of them’.), and to the Guildhall (‘splendid exhibition’). She returned to Westminster Art School in October and on the 4th recorded ‘Lucy and I went to town today for the summer sketch criticisms at school of art. Mr Loudan presented me with £3, as third prize for the year’s composition sketches. Delightful surprise..’

In the autumn of 1897 Lena and Lucy travelled over to Park Walk, Chelsea, to visit the complex of the Stanley Studios, where Sophie Pemberton was based. Sophie’s star was on the ascendant; that year she had exhibited for the first time at the Royal Academy summer exhibition. Unfortunately there was no studio available there, and with Ethel Le Rossignol, a school friend with whom they proposed to share and who much later became a practitioner of spirit-channeled art, Lucy and Lena embarked on a search. By the end of November they had found a studio, at a rent of £35 a year – and were very pleased with it. They had fun arranging to move in, buying things with which to decorate, including a new stove and oriental rugs. Lena hired models and also arranged for family and friends to sit for her. The studio gave the sisters an opportunity to invite round their friends, in a way they probably did not do at home. On 6 March ‘Barbara Nightingale came to tea at studio yesterday’. [Barbara Nightingale was the same person as Barbara Shore-Smith – there had been a change of family name.] In April Lucy had a picture accepted by the Royal Academy, Lena describes the subject as being 3 parrots; the exhibition catalogue gives it the title ‘Red, White and Blue’. The picture was sold to a Captain B for 7 guineas.

In 1899 and 1900 Lena continued working from the studio, concentrating on pictures to submit to the Royal Academy. However they were all rejected or crowded out. In the summers, with Lucy and Ethel Le Rossignol, she took sketching lessons from professional artists, the first year in Mayfield in Sussex and the next summer at Brockham Green in Surrey. In November 1900 she returned to the Westminster Art School, taking lessons in modelling from life.

She also began to learn metal repoussé, possibly at the Westminster School – her diary is not entirely clear on the point. Lena was following the spirit of the times. There had in the last five years been a definite upsurge of interest in craft work. Lena, however, quickly gave up this class in order to attend a modelling design class at St John’s School of Art and Science at New Cross, where a Mr Miller and a Miss Jean Milne, who had been fellow students at Westminster, were master and assistant mistress. Lena placed the receipt for the course (10/- for the term ending 12 April) between the pages of her diary and began modelling a door knocker.

However, for whatever reason, at the end of the term she did not continue at New Cross, but went over to Chelsea to investigate the modelling class at the South West Polytechnic in Manresa Road. She duly joined that class and ‘settled to join the handicraft studio for metal repousse on Tuesday afternoons’. In May she sat a Modelling Design exam, which she passed 1st class, and a Life exam and was awarded a book prize in the National Competition work at South Kensington for her ‘head of Papa’. The National Competition was run by the Science and Art Department of the Committee of the Council on Education and several thousand students from art schools around the country competed for the prizes.

In October Lena began classes again, taking a modelling life class at the Manresa Road Polytechnic and one in modelling design at St John’s. She was also doing metal work, perhaps at the polytechnic. I think she must have given up her studio some time before this and in November (1902) when she decided to make a commitment to metal work and bought a muffle furnace, she made her workshop at home in the harness room. In December she went over to Whitechapel to the Sir John Cass Institute ‘as I think of going there for metal work and design after Christmas’. The Sir John Cass Institute had only opened the previous June so Lena was obviously well aware of developments in the field of craft education. She then left the St John School of Art at New Cross and in January 1903 ‘started work at the Sir John Cass Technical Institute’. The head of the Arts and Crafts Department was Richard Llewellyn Rathbone, Harold Stabler was teacher of drawing and design, Gilbert Bayes was teacher of modelling, and there were also teachers of jewellery and enamelling.

Lena took the enamelling class on Tuesday evenings, jewellery on Wednesdays and design on Fridays. During the day on Tuesdays she still attended modelling classes at the Polytechnic.

She continued with these classes until the end of the summer term and then went to Walberswick with Lucy to take sketching lessons from Bertram Priestman. She returned to the Cass in October and found that Jean Milne was also now working there. Among her fellow students were Violet and Frances Ramsay and Thalia How. She attended the Cass for all three terms that year and returned to Walberswick in September for two more weeks of sketching with Bertram Priestman.

When she returned to the Cass in October 1904 she learned that she had received a book prize for a figure she had sent up to the National Competition. She once again rented a studio, this time in Tachbrook Street. Lena was now established in her jewellery making; a pendant she had made was given to Barbara Nightingale as a wedding present as she embarked for India to marry ‘a Mr Stephens’. In her studio she began modelling a bust of her father and began another happy round of studio teas; Jean Milne and Thalia Howe were among the guests. She continued at the Cass throughout 1905, receiving a prize for metal work at the end of the year.

In January 1906 she had at least two pendants accepted for the Arts and Crafts Exhibition at the Grafton Galleries. One of her pieces was described in the Exhibition catalogue as a necklace and enamel pendant and was priced at £2 12s 6d. There was increasing organization in her area of the art world and in April she notes the first meeting of the Sir John Cass Arts and Crafts Society and in May that she had ‘applied to join a new club called the United Arts Club.’ The Studio reported that as ‘it is hoped the club will become a recognised medium for effecting sales, it was of importance to establish at the outset the standard of work which will entitle members to the privilege of having their work included in the quarterly exhibitions’. Lena was accepted as a member.

In June the Sir John Cass Arts and Crafts Society held its first exhibition and Lena noted in her diary ‘One of mine is to be photoed for the Art Journal’. In fact the December 1906 issue of the Art Journal includes both a silver necklace and a copper and enamel candlestick by Madeleine Martineau. Among the other pieces photographed were a copper tea caddy by Jean Milne, a pendant each by Thalia How and Violet Ramsay and a brooch and a necklace by Harold Stabler.

In November 1907 at the Cass annual show Lena exhibited two jewel cases and a metal fruit dish with a figure pedestal. In December she received a prize from the Cass Institute, the book selected being a copy of Lewis Day’s Enamelling. In May 1908 she ‘took up a case of jewellery to agents for Liverpool exhibition’, in November she was exhibiting at the Sir John Cass society show and also sent a case of jewellery to a show in Cambridge. At the end of the month she ‘took a case of jewellery to the United Arts Club and another to the Lyceum Club’. From the Cambridge show she received a first class certificate.

She does not mention if any items were sold from these exhibitions. In February 1906 she had noted that a ‘pendant I sent to show at Alderley Edge has 2nd prize and is sold to Katherine Greg’ and that from the Cass show in November 1907 ‘one thing of mine was bought, a copper clasp’. In February 1909 came her first commission. The relevant entry reads ‘I have been to Club today to meet lady who wishes for a gold medal to be made for the poets club to award the best poem’. The lady was a Mrs Higginbotham and the Club was the United Arts. Lena began the medal on 11 April and delivered it two months later. She had not been working at it all this time; she had enjoyed a two-week holiday in Italy. However on 20 July she received ‘ a rude letter from Mrs Higginbothom this morning refusing to take the medal, and saying it is not worth more than 15/- to a guinea!. Tho all 18ct gold with pearls and enamel.’ Lena reported the matter to the Club who arranged for her to make an appointment to speak to Mrs Higginbotham in person.

However Harold Stabler advised her not to go but to write. The matter ended with Mrs Higginbotham returning the medal to her. There is no mention of her ever receiving another commission. She kept busy in the autumn, exhibiting jewellery at an exhibition in Dresden and at the Cass society’s annual show.

In January 1910 she took a case of jewellery and an epergne to the New Gallery for display at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition and two cases of jewellery to the Society of Women Artists. She is noted as an exhibitor in the catalogues of both exhibitions. Her work shown at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition included a gold pendant and chain, entitled ‘ St Cecilia’; a gold necklace, a gold enamelled pendant and a gold necklace with tourmalines. For what it is worth it so happens that in the copy of the catalogue held by the British Library Lena Martineau’s pieces have been annotated in the margin in pencil. There are very few other markings – Cobden Sanderson’s books are so marked – and the impression is that the holder of the catalogue walking around the exhibition had approved of her pieces. There is no indication, however, of whom this visitor was.

In February 1911 she won 1st prize in the competition organised by the Studio for the design for a necklace pendant . The prize was 3 guineas – and, of course, her name was published in the magazine. In June when the Studio reported on an exhibition organised by the Sir John Cass Arts and Crafts Society it mentioned that ‘the jewellery included a dainty gold necklace by Miss Martineau’. Then on 24 November her father died. For whatever reason after this she made very few diary entries and the diary ends, at the bottom of the final page of the book, on 19 March 1914. I do not know if she carried on with her diary beyond the final 1914 entry. Until November 1911 entries had been made quite regularly and contain far more detail than I have been able to include in this paper.

Moreover, in the few 1913 and 1914 entries she makes no mention of any artistic endeavour. However, a (February, I think) 1914 article in the Studio ,‘Some Examples of Modern English Jewellery’, is illustrated with what the magazine says is ‘a small selection of recent work by artists whose productions are familiar to exhibition visitors’. Among the artists so recognized was S. Madeleine Martineau, with an ‘enamelled gold pendant with four pears, wreath and bird repousse’.

As the Studio describes the work illustrated in the article as ‘recent’ it is likely that this piece was less than three years old, – that it was in fact made in the period after the last mention in her diary of her jewellery work. However, when the next Arts and Crafts Exhibition was held in 1916 Lena Martineau was not an exhibitor, although Violet and Frances Ramsay, Jean Milne and Thalia How all were. This would seem to be reasonably definite proof that she was by then no longer part of the arts and crafts scene.

But life has odd quirks. It was because the bird piece had been photographed for the Studio that when it was bought c. 1973, as part of a collection, by a dealer specialising in art nouveau jewellery, he was able to identify its maker. As Lena Martineau only died in 1972 – aged over 100 – my surmise is that the piece, along with others in the same collection, had remained with her all her life and had formed part of her estate. Once the dealer was able to identify this piece, others in the same collection were attributed to her.

Around the same time, interest in arts and crafts and art nouveau jewellery was developing, and two books by Vivienne Becker, Art Nouveau Jewelry and Antique and Twentieth Jewellery: a guide for collectors, drew on this art nouveau dealer’s stock of photographs for illustrations. A few facts about Lena Martineau’s life were surmised, mostly incorrectly.

It is not my contention that Lena was a feminist icon, a forgotten heroine. What is interesting about the life revealed in the diary is its very ordinariness. She had no struggle to receive her art education; her family backed her in her attendance at classes, in renting studios, and by sitting for her. Her diary reveals how much freedom a young woman – 20 when it opens – had in following her inclinations in this direction. There is nothing in her diary to suggest that she felt thwarted or discontented in any way. Moreover, whether or not she deserves the accolade, Sarah Madeleine Martineau has now entered the canon as an arts and crafts jeweller, the presumption being, merely because she is included, that her work was exceptional. However, in reality it is only because it has been possible to identify a little of her work – although that certainly is because she was considered by her contemporaries (except for Mrs Higginbotham) as being more than competent – that she has received this measure of recognition. Her diary gives a fascinating glimpse into the life behind the pendants.

Sarah Madeleine’s Manuscript Diary is now held in the collection of The Women’s Library@LSE.

Copyright