An Army of Banners

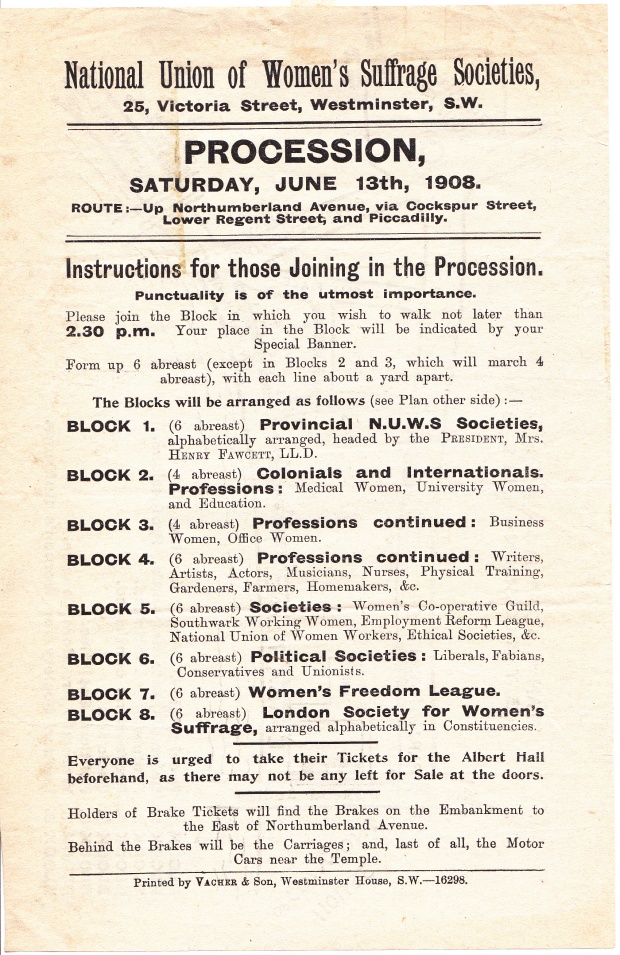

In June 2008 I was invited by The Women’s Library to give a talk on suffrage banners to mark the 100th anniversary of the first of a new style of spectacular processions staged by the British women’s suffrage movement. For it was on the afternoon of Saturday 13 June 1908 that over 10,000 women belonging, in the main, to the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies processed through central London to the Albert Hall, where they held a rally.The image above was that used to publicise the procession.

In June 2008 I was invited by The Women’s Library to give a talk on suffrage banners to mark the 100th anniversary of the first of a new style of spectacular processions staged by the British women’s suffrage movement. For it was on the afternoon of Saturday 13 June 1908 that over 10,000 women belonging, in the main, to the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies processed through central London to the Albert Hall, where they held a rally.The image above was that used to publicise the procession.

The talk I gave was accompanied by a Powerpoint illustrating all the designs for the banners mentioned or, indeed, the banners themselves. Although, or copyright reasons, I am unable to insert these illustrations directly into this article I have provided links on which you can click to see them for yourselves.

And what was the reason for the procession?

And what was the reason for the procession?

It was to draw the country’s – and the government’s -attention to the women’s demand that they should be given the vote – on the same terms as it was given to men.

Yet by 1908 the campaign was already 42 years old. Since 1866 thousands of meetings had been held in cities, towns, villages, and hamlets throughout the entire British Isles – from Orkney to Cornwall and from Dublin to Yarmouth. Some of these had been no more than small gatherings in cottages, others had been held in middle-class drawing rooms, in Mechanics’ Institutes, in market places and in church halls – while many others had been held in the largest public halls of the largest cities of the land. Yet despite all this activity women had not achieved their goal.

At times they had thought they were coming close – when, for instance, a franchise bill managed to jump a few of the parliamentary hurdles. And 1908 was one of those times. In 1906 a Liberal government had been elected – and the suffragists, despite many past disappointments, always had higher hopes of the Liberals. And now, just a few months previously, in February 1908, a Liberal MP had introduced yet another women’s suffrage bill in Parliament – and it had actually passed its second reading – before being blocked. Another failure, of course, but this was the greatest progress that a suffrage bill had made since 1897. The leaders of the NUWSS thought that the time was ripe to capitalise on this quasi- success and show the country how well-organised and united women could be in publicising their claim to citizenship. Incidentally there was also a new prime minister to impress. Asquith had just taken office in April, succeeding the dying Campbell-Bannerman.

The image used on the advertising flyer for the procession was also used a little later on the badge given to those organising local NUWSS societies throughout the country. We can see that the bugler girl is calling her comrades to rally to the banner – and it was banners that were recognised at the time – and are remembered today – as the most significant visual element of that procession a hundred years ago.

The journalist James Douglas, reporting for the Morning Leader put it rather well ‘They have recreated the beauty of blown silk and tossing embroidery. The procession was like a medieval festival, vivid with simple grandeur, alive with an ancient dignity.’

‘Blown silk and tossing embroidery’- a wonderful phrase – conjuring up an alluring image.. In fact a high wind that afternoon meant that the silk was certainly blown and the embroidery tossed.

And his observation that the procession was like a medieval festival – invoking concepts of ‘grandeur’ and of ‘ancient dignity’ – was just what the organisers were aiming for. The designer of the majority of the banners was Mary Lowndes, a successful professional artist, very much a product of the Arts and Crafts movement, who specialised in the designing of stained glass. A year later she put down on paper her thoughts on ‘Banners and Banner Making’, tracing women’s involvement in this craft right back to the ‘warrior maidens’ of a romanticized – if not an entirely mythical – medieval past. She lamented the use in recent years of manufactured banners – the implication being that these were carried by male groups – both civil or military – but that ‘now into public life comes trooping the feminine; and with the feminine creature come the banners of past time’ She applauds what she calls ‘the new thing’ – writing that by this she means the ‘political societies started by women, managed by women and sustained by women. In their dire necessity they have started them; with their household wit they manage them; in their poverty, with ingenuity and many labours, they sustain them.’

The NUWSS had actually staged its first procession through the streets of London the previous year – in February 1907. This had had a startling novelty value – it really was the first time that large numbers of middle-class women had taken to the streets. On that occasion, too, banners had played their part. However February was not a good month for a procession – it was not for nothing that the occasion acquired the soubriquet the ‘Mud March’(for more about the Mud March see here). To be fair – the timing of the procession had been chosen with a purpose – to coincide with the opening of parliament (which was then held in February). However the NUWSS organisers learned from their mistake and June was chosen as a more suitable season for their second public procession.

This particular June Saturday was selected because the International Conference for Women’s Suffrage was about to be held in Amsterdam – it was starting on Monday 15 June. This meant that many important delegates from around the world were passing through London and were able to take part in the British demonstration. The other main suffrage organisation, the WSPU – the Women’s Social and Political Union – had chosen the following Sunday, 21 June, on which to stage their most ambitious rally yet – it was to be known as ‘Woman’s Sunday’– processions culminating in a rally in Hyde Park. The two events have sort of rolled into one in the popular memory – but the NUWSS procession was the first of the two. The WSPU, too, carried a brilliant display of banners – but most of theirs were made by commercial manufacturers and, sadly, none seems to have survived.

This particular June Saturday was selected because the International Conference for Women’s Suffrage was about to be held in Amsterdam – it was starting on Monday 15 June. This meant that many important delegates from around the world were passing through London and were able to take part in the British demonstration. The other main suffrage organisation, the WSPU – the Women’s Social and Political Union – had chosen the following Sunday, 21 June, on which to stage their most ambitious rally yet – it was to be known as ‘Woman’s Sunday’– processions culminating in a rally in Hyde Park. The two events have sort of rolled into one in the popular memory – but the NUWSS procession was the first of the two. The WSPU, too, carried a brilliant display of banners – but most of theirs were made by commercial manufacturers and, sadly, none seems to have survived.

An announcement that the NUWSS procession was to take place on 13 June was made in a letter that appeared in the Times on 8 May. This was signed by leaders of the NUWSS, including Millicent Fawcett, the president. The letter stated that ‘Professional women, University women, women teachers, women artists, women musicians, women writers, women in business, nurses, members of political societies of all parties, women trades unionists, and co-operative women all have their own organizations and will be grouped in the procession under their own distinctive banners, which have been specially designed for the occasion by the Artists’ League for Women’s Suffrage.’ The letter then appealed both for funds to help pay for the banners and ‘for the personal support and presence in the procession of women who conscientiously hold that every kind of constitutional action should be taken in support of the rights they claim.’

So what was this Artists’ Suffrage League?

It had been founded in January 1907 by Mary Lowndes to involve professional women artists in preparations for the Mud March. Among the founding members were an Australian artist, Dora Meeson Coates, and Emily Ford, whose sister, Isabella, was a member of the procession’s organising committee. The Fords came from a Leeds Quaker family with a long history of involvement in the suffrage movement. Emily was by now living and working in a studio in Chelsea, a close neighbour of Dora Meeson Coates and of other women artists who supported the suffrage cause. The ASL’s secretary was Barbara Forbes, Mary Lowndes’ companion – and sister-in-law – who worked alongside her in her stained glass business.

The Artists’ Suffrage League representatives on the NUWSS committee organising the 13 June procession were Mary Lowndes and Mrs Christiana Herringham. In 1903 Mrs Herringham had been the originator of the National Arts Collection Fund, which made its first purchase of a painting in 1906. Ironically this was Velazquez Rokeby Venus, which in 1914 was to be badly damaged by the action of a militant suffragette, Mary Richardson (for more about this incident see here and here). Mrs Herringham had been a supporter of suffrage societies since at least 1889, and by 1907 was subscribing to both the NUWSS and the WSPU.

In a letter to the Times that appeared on the day of the procession, Millicent Fawcett noted that, besides Mary Lowndes and Emily Ford, other artists involved in the production of the banners included May Morris, daughter of William Morris, and Mrs Adrian Stokes – she was an Austrian artist, Marianne Stokes, who had been a friend of Millicent Fawcett for some years – for instance they were both staying with mutual friends at Zennor in Cornwall when the 1891 census was taken. From newspaper reports it would appear that ’80 ladies’ had been involved in the production of 70-80 embroidered banners that were made specifically for this procession – and that they had been working on them since the beginning of the year.

Amazingly – of the banners made by the Artists’ Suffrage League for this procession many are still in existence – most of them held in the Women’s Library@LSE, with another selection housed in the Museum of London. We are extremely fortunate in that not only have the banners themselves been preserved, but so have the original designs. For in the Women’s Library collection is the actual album in which Mary Lowndes sketched out her designs for the banners, the colours to be used indicated in watercolour, and, in many instances, with swatches of likely fabric also attached. However, the designs that were included in the album are not dated and one cannot assume that all necessarily relate to banners designed for the June 1908 procession. For instance the album contains a design for a banner for the Manchester Federation of the NUWSS– but the Federation didn’t come into existence until 1910. So I have tried to be careful and to relate the designs to the reality of the banners as described in newspaper reports of the day. There are a few newspaper photographs of sections of the procession but, on the whole, they are not as helpful in identifying specific banners as are the words that accompanied them. The NUWSS missed a trick in that, unlike the WSPU the following week, they did not think of publishing photographs of the procession as postcards.

However the procession – and its banners – certainly did attract columns of newsprint – a good selection of which were carefully cut out and pasted up in another album kept by the Artists’ Suffrage League. In fact a leaflet was printed by the NUWSS containing extracts from the press reports specifically about the banners.

The ASL banners had been on display in Caxton Hall, Westminster, for a couple of days before the procession – and the press had been invited along to view them. The Daily Chronicle reporter had clearly got the message – writing that ‘the beauty of the needlework.. should convince the most sceptical that it is possible for a woman to use a needle even when she is also wanting a vote’.

It was not only the skill of the needlewomen that was remarked on. The Times was always rather loathe to give any credit to the suffrage cause, but was prompted – after its usual weasel words casting doubt as to whether the procession caused ‘great masses of the people to be deeply moved on the suffrage question’-, to admit that ‘in every other respect its success is beyond challenge. To begin with, the organization and stage-management were admirable, and would have reflected credit on the most experienced political agent. Nothing was left to chance or improvisation: and no circumstance that ingenuity or imagination could contrive was lacking to make the show imposing to the eye. Those taking part in the demonstration were all allotted their appointed stations, and every care had been taken to enable those stations to be found with the greatest ease.‘

It was 3 o’clock when the start was made. At the head was borne the banner of the NUWSS, on which was inscribed the legend ‘The franchise is the keystone of liberties’. Beneath the folds of this banner – which has not survived – marched Lady Frances Balfour and Mrs Henry Fawcett, wearing her cap and gown – the robes of her honorary doctorate from St Andrews University.

Then, as the Times, reported, came all the provincial detachments. The NUWSS could trace its descent from the first suffrage society that had been formed in 1866 – but by 1908 it had been transformed out of all recognition from this first, very tentative, incarnation. Through the 19th century local groups had been formed in towns and cities around the county, aligning themselves with the main societies – in London, Manchester, Bristol, Birmingham and Edinburgh. In 1896 they all grouped together under the umbrella of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. The NUWSS had continued to develop and in 1907 had adopted a new constitution and strengthened its organisational structure. The provincial societies, although they had a measure of autonomy, were given strong leadership from the London headquarters. But it was the London Society, under the command of Philippa Strachey, that was responsible for the organisation of the procession – just as she had the Mud March the previous year.

It was important to the organisers that it should be made clear that the procession was representative of women of the entire country – which was why so much emphasis was given to indicate on the banners the names of the towns from which they came. As a convenient shorthand the designs for these banners used existing emblems associated with the town or region. The Westminster Gazette took the point, commenting that ‘Nothing like them for artistic skill, elegance and emblematic accuracy – to say nothing of their great number – has ever been seen in a public demonstration of this kind before.’

And the Scotsman reported, ‘The most remarkable feature of the procession was the great display of banners and bannerettes. It was said there were as many as 800 of them, and the designs and mottoes which they bore appeared to be almost as numerous. Many of them were effective works of art, and bore striking inscriptions’. Unfortunately few of these local, provincial, banners are amongst those that have survived. They would have been taken back to the home town and were certainly then used in many other local demonstrations – before, I suppose, eventually becoming damaged or forgotten. That is why it is so fortunate that we have Mary Lowndes’ original designs as a record of what has disappeared.

The provincial detachments processed in alphabetical order. First came Bath, then Birkenhead, Birmingham, Blackburn, and Bradford. Of these we have no record of either the design or the banners themselves – which were probably designed and made locally.

But then came Brighton. And I know that this Mary Lowndes design really was made up into the banner carried on the day – because it appears in a photograph published in the Daily Mirror. The dolphins were a long-established symbol of the town – appearing in the Brighton coat of arms and ‘In deo fidemus’ was certainly the town’s motto at the beginning of 20th century. The swatches attached to the album design, however, indicate that the colours used were dark and light green and gold – rather than blue that appears here

By 1908 the Brighton Society had over 350 members and as Brighton is close to London the society should have been able to produce a sizeable contingent of supporters to walk with their banner.

I found this next design particularly interesting, referring as it does to the Bristol Women’s Reform Union –not a name that will be very familiar even to close students of the suffrage movement – which is why it is rather exciting to see its existence given credence by this design. The society had been founded in the early 1900s by Anna Maria and Mary Priestman from Bristol – radical liberal, Quaker campaigners – whose involvement went back to the very first years of the suffrage movement. The Reform Union existed in parallel to the main suffrage society in Bristol, but aimed to set the question of the suffrage in the context of wider social reform. It finally amalgamated with the Bristol NUWSS society in 1909.

Next came Cardiff – one newspaper reporting that the ‘Dragon of Cardiff excited general attention’. There is no design for Cardiff in the Lowndes album it is more than likely that it was made by members of the newly-formed Cardiff and District Women’s Suffrage Society and is the one that has now (in 2016) been donated to the Special Archives and Collection of Cardiff University (for the full story see here).

Next came the women of Cheltenham. The town had over the years proved to be a very effective centre of the suffrage campaign in Gloucestershire. A fashionable spa, the town was attractive to single women of means. In 1907 the town had collected 900 signatures to the Women’s Franchise Declaration – another in the long series of mammoth petitions that had been presented to parliament. The Cheltenham banner has not survived – but a newspaper report does tells us that it bore the motto ‘Be Just and Fear Not’

The design of this next banner – beneath which marched the women of East Anglia – had been, in part at least, suggested to Mary Lowndes by Millicent Fawcett – an East Anglian herself – whose hometown was Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast In her report of the procession that appeared in the Times on the big day, she particularly mentioned this banner – writing that it ‘shows the three crowns of the East Anglian St Edmund and a representation of the wolf traditionally associated with the miraculous preservation of the martyr’s head – and the motto – Non angeli, sed Angli’. Many of the elements – the three crowns and the wolf – are still in the coat of arms of Bury St Edmunds. The wording is the reverse of what Pope Gregory is reputed to have uttered when, in 573AD , he was shown some captive British children in Rome – that is ‘Not Angles, but Angels’ – the rewording is supposed to mean ‘Not angels, but Angles – that is, citizens.’ A nice hit at the ‘Angel in the House’

And here is a photograph taken on the day – showing the banner with in front from left to right, Lady Frances Balfour, Millicent Fawcett, Emily Davies and Sophie Bryant, headmistress of North London Collegiate.

And here is a photograph taken on the day – showing the banner with in front from left to right, Lady Frances Balfour, Millicent Fawcett, Emily Davies and Sophie Bryant, headmistress of North London Collegiate.

For the Mud March the previous year Millicent Fawcett had not worn academic dress –but it had been decided that today it would be worn – to imbue the occasion with as much dignity as possible . Next to her, with bonnet, bag and umbrella, is Emily Davies who, in 1866, with Elizabeth Garrett, had handed to John Stuart Mill the very first women’s suffrage petition. She was now 76 and yet was still to be around, in 1918, to cast her vote for the first time. One newspaper reported Emily Davies saying on 13 June ‘It is a great day for the movement, I would not have missed it for the world.’

Scotland was, of course, represented in the procession. Here is Mary Lowndes’ design for the banner – and here is the reality. The black and red, triple-towered castle is as it appeared at the time on the city of Edinburgh coat of arms – with the thistles added to highlight Scotland’s commitment to the cause.

The next banner of which we have a record is that for Fleet, in Hampshire..I must admit that when I saw the design for this banner in the Lowndes album I was a little doubtful as to whether the town of Fleet would have mustered a contingent for this particular procession – there is no record of a suffrage society in the town at this time. But to my delight I came across a newspaper report that specifically mentioned this banner – which was made up, as shown, in yellow and orange – and with the motto as depicted – ’Delay of Justice is Injustice’ – an ancient proverbial concept – the wording put into this form by Walter Savage Landor. Because this Fleet banner was proved to be ‘right’ I have extrapolated from this that so are other Surrey and Hampshire ones the designs for which are in the Lowndes album

Thus Guildford is just such a one – depicting Guildford castle and two woolpacks – anciently the town’s staple trade– both of which feature on the Borough of Guildford coat of arms today. A Guildford NUWSS society was definitely formed in 1909 but I don’t think that there was one in 1908. However this area of Surrey was the home of women who were not only committed suffragists – but who also had long association with the Arts and Crafts movement – and clearly the combination of suffrage and needlework was appealing. Christiana Herringham’s sister, Theodora Powell, was the secretary of the Godalming society formed in 1909 – and she was also instrumental in the founding of the Guildford society. The president of that was Mrs Mary Watts, widow of the artist, G.F. Watts

By the way, a later Godalming banner was worked by Gertrude Jekyll and is now held in a local museum.

Next came the banner of Haslemere and Hindhead – a banner of which we know – although it is now lost – because it was described in the press reports

It bore what might appear the surprising motto:

‘Weaving fair and weaving free

England’s web of destiny’

At least one scholar has assumed that Haslemere – then a small sleepy Surrey town – could not have been associated with the weaving industry – and, as one can so easily do, made the assumption that a Lancashire name with a similar name must have been intended – but in 1908 Haslemere did support a weaving industry – of a sort. It was far removed from the dark satanic mills of Lancashire – but had been founded in 1894 as a branch of the Peasants Art Society – weaving cotton and linen. Haslemere was in fact a haven of an artistic community. By 1909 it, too, like Godalming and Guildford, had its own NUWSS society. The chairman was Mrs Isabel Hecht.

The next banner in the alphabetical procession was that of North Herts, which, according to the press report, ‘declared in black and white that it was undaunted’. To put it more prosaically the banner included the wording ‘North Herts’ and ‘Undaunted’. It had been known as the Hitchin Suffrage society – but became North Herts Women’s Suffrage Association, with Lord Lytton as its president – his sisters, Lady Betty Balfour and Lady Constance Lytton were also associated with the society, though Lady Constance was, of course, much more famous for her association with the WSPU. One of the secretaries of the Association, Mrs Edward Smithson, who lived in Hitchen, had been a founder member in the 1880s of the York Suffrage Society – an example of the dedication that many women, whose names are not now remembered, had given over decades to the suffrage cause.

Next came Huddersfield. There is a Huddersfield banner still extant, held in the Tolson Museum in Huddersfield. It, too, is a work of art, designed and made by a local suffragist, Florence Lockwood – depicting local mills and with the motto ‘Votes for Women’. This wording might more usually be associated with the WSPU than with the NUWSS, but Florence Lockwood definitely gave the banner to the local NUWSS society. However I rather think that it post-dated 1908 – and was probably not the one carried in the 1908 procession

Hull’s banner, however, probably was – although it wasn’t singled out for mention in any newspaper report. In fact the Hull NUWSS society, which had been founded in 1904 by Dr Mary Murdoch, sent the largest contingent of any provincial society to walk in this suffrage procession. Local members subscribed over £100 to meet the expense of the trip and hired a special train for the occasion .The device of the three crowns is still used today on the city coat of arms

Keswick, too, had a banner in the procession – described as an ‘exquisitely painted view of Derwentwater’. In fact the Keswick society had two banners at its disposal – the one that Catherine Marshall, the young and energetic secretary of the society, refers to at one point – with no further description – as ‘our banner’ and a private one lent by her cousin’s wife, Mrs John Marshall of Derwent Island. It is possible that it was to this one that the press report referred. The ‘our banner’ one is, I think, the one that still exists, with Catherine Marshall’s papers in the Cumbria Record Office.

A Kingston NUWSS society was formed in 1908 – here is the design for its banner. The swan seems to have been a fanciful device conjured up by Mary Lowndes– the Kingston coat of arms at the time sported three salmon – with no mention of a swan.

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph commented particularly on the Leeds banner, noting ‘One device with the golden fleece bore the phrase ‘Leeds for Liberty’’ – so we can be certain that this banner was indeed carried in the procession. Leeds had a long history of involvement in the suffrage movement. The fleece, three stars and owls all derive from the Leeds coat of arms . ‘Leeds for Liberty’ certainly has a heartier ring to it than the city’s motto, which was (and is) ‘Pro Rege et Lege’ (for King and the Law). Annotation on the design shows that the banner was 4ft 4” wide by 6ft 6in high. ‘With bamboo poles and cords complete £2. The lovely blue and gold strips are given by Mrs – Herringham. The owls are silver.’

Leicester, too, had a long history of involvement in the suffrage movement. By 1908 there had been a local suffrage society in the town for 36 years and here is Mary Lowndes’ design for their banner.

After Leicester came Liverpool. The Liverpool NUWSS society had taken its banner very seriously – commissioning a local artist to design it. It is a most impressive work of art – featuring a Liver bird and a galleon and carrying the message – ‘Liverpool Women Demand the Vote’. The society had opened a shop in Bold St, one of Liverpool’s most fashionable thoroughfares, and in the days before the procession, displayed the banner there. On 13 June members of all Merseyside branches accompanied their banner to London, travelling on specially hired trains. The banner still exists – now in the care of Merseyside Museums.

The next design – that for a banner for Newcastle – highlights the difficulty of assigning a date to a design. Newcastle certainly had a banner in the June 1908 procession – but I am not convinced that it was this one, designed by Mary Lowndes. Newspaper reports of the June procession describe Newcastle’s banner as carrying the message, ‘Newcastle demands the Vote’ – perhaps along the lines of the Liverpool one. Needless to say the three castles do feature on the city’s coat of arms – of which red, white and black are the dominant colours. The design may have been changed, or used on another occasion.

Next came North Berwick. An attractive design – and the town’s coat of arms does includes the ferry boat. I haven’t come across a suffrage society specific to North Berwick, but there were clearly women from the town who were sympathizers.

Next came the banners of Nottingham and Oxford. We know that the members of the Oxford society cooperated with the Birmingham society to reserve seats on a special train and that 85 members travelled to London on the day, accompanied by their banner. Unfortunately, however, it doesn’t appear to have survived.

Portsmouth women, too, carried a banner – remarked on by the press for its motto, echoing Nelson, ‘Engage the enemy more closely’. It, too, has disappeared

We do, however, have a record of the design of Purley’s banner – although I don’t think Purley ever supported a suffrage society – but it presumably formed part of the Surrey coterie – its banner designed by Mary Lowndes. I must say that, although I have been able to decode most symbols on the banner designs, I couldn’t fathom out why this one should have what appeared to be shamrocks across the top. But they may, just possibly, be oak leaves – the Purley oaks – an ancient local landmark – feature in one version of an old coat of arms

Next in the alphabetical order came Reading. And there was a Reading banner – for newspaper reports mention that ‘A dozen women tugged at the ropes of the big banner of Reading to prevent it being blown over’. Alas it has vanished.

Likewise there was a banner for Redhill, and one for Sevenoaks, the latter carrying the motto, ‘What concerns all should have the consent of all’, and for Stratford-on-Avon. All have disappeared.

We do, however, have the design for the Walton banner – again part of the Surrey group.

The Warwick banner was designed by Mary Lowndes. I haven’t been able to establish that the motto has any significant relevance to the town. But it is a good strong message

By way of contrast the West Dorset design in the album is very faint – the faintest of all. Whether or not it was made up I am not sure – nor whether it was carried in this procession – but it is evidence that even in that quiet rural area women suffragists were sufficiently stirred to request a banner to represent them.

The Woking banner carries the motto ‘In arduis fortitudo’- fortitude in adversity’. I think the design displays a degree of artistic licence – the town didn’t receive a coat of arms until 1930. An NUWSS society was formed in the town in 1910 – and of course the fact that one of its residents, Ethel Smyth, gave sanctuary to Emmeline Pankhurst when she was released from hunger striking, did ensure it some suffragette notoriety.

We know that contingents of supporters from Worcester and York – together with their banners – also took part in the procession – but neither banner has survived.

A large Irish contingent was also present – marching under at least one banner, which I have seen faintly in a newspaper photograph. And with the marchers were Thomas and Anna Maria Haslam, both of whom had been leaders of the campaign in Ireland since 1866 – and both of whom were now over 80. It is an indication of how seriously the procession was taken that, despite age and infirmity, they had made the effort to travel over from Dublin to take part in the procession.

The local societies were followed by a group of colonial and foreign representatives, many of whom, as I have already noted, were passing through London that weekend on their way to Amsterdam. It was, of course, thought appropriate that some women pioneers of countries other than England should be commemorated by this group.

Advance knowledge that this was to happen had irritated one correspondent to the Times, for, writing from Kensington on 10 June, ‘E.M. Thompson’ had declared, ‘A few days ago I found a youthful adherent of the suffragist cause industriously embroidering a woman’s name on a small bannerette intended for the great occasion. Neither she nor I had ever heard of this lady before, but my devoted young friend was quite satisfied with her task, and informed me that it was the name of an “American pioneer, now dead”. Personally I have no particular wish for a vote, but under any circumstances I should most emphatically refuse to march under an American banner in company with Russian, Hungarian and French women, to demand from the English government a vote to which I considered that I was entitled as an Englishwoman. It seems to me little short of impertinence for those who, up to the present, have failed to get votes in their own countries, to interfere with our home politics, and by swelling the size of the procession to help to give a wrong impression of the number of women in England in favour of the movement.’

I wonder which of the ‘American pioneers, now dead’ was being commemorated in embroidery by that industrious young suffragist? Banners had certainly been made to flaunt the names of Susan B Anthony, Lucy Stone and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The two former banners are still held in the Women’s Library.

I wonder which of the ‘American pioneers, now dead’ was being commemorated in embroidery by that industrious young suffragist? Banners had certainly been made to flaunt the names of Susan B Anthony, Lucy Stone and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The two former banners are still held in the Women’s Library.

The Elizabeth Cady Stanton one, however, is not with them. It was assumed to be just missing – that is ‘missing’ in a general sense – like many other of the banners. However when undertaking this research, I discovered that in August 1908 this particular banner had been sent over to New York – sent by Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter, Harriot Stanton Blatch, to whom it had been presented. She and her daughter, Mrs de Forest, had been present at the Albert Hall meeting on 13 June. As the New York Times reported ’The most gorgeous souvenir is the “Elizabeth Cady Stanton” banner of white velvet and purple satin that was used to decorate the Albert Hall. The name is embroidered in enormous letters in purple and green, the suffrage colours, and the whole mounted on a background of white velvet).’ As you can see from this report there was already some confusion as to what constituted suffrage colours. The purple, white and green combination was first used by the WSPU the following Sunday – for their Hyde Park rally. But there is no doubt that the Elizabeth Cady Stanton banner was carried in the NUWSS procession on 13 June.

Among those marching with the American contingent were women representing the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women of New York, the organisation founded by Harriot Stanton Blatch in 1906 – and which later changed its name to the Women’s Political Union. Also present were the niece of Susan B. Anthony and the Rev Anna Shaw, who was one of the speakers at the Albert Hall meeting. She specifically mentioned that she and her fellow Americans had not come to tell British lawgivers what to do for the women of this country – they could do that for themselves – but to extend to them the right hand of comradeship in the warfare which they were waging. A statement that was greeted, according to the newspaper report, by cheers.

The Commonwealth of Australia was represented by a banner – painted rather than sewn – that had been designed by Dora Meeson Coates. It bore the message ‘Trust the Women Mother As I Have Done ‘, a reference to the fact that Australia had granted women the vote 6 years preciously, in 1902. That banner was given by the Fawcett Library to the Australian government in 1998 and now hangs in Parliament House in Canberra.

The Commonwealth of Australia was represented by a banner – painted rather than sewn – that had been designed by Dora Meeson Coates. It bore the message ‘Trust the Women Mother As I Have Done ‘, a reference to the fact that Australia had granted women the vote 6 years preciously, in 1902. That banner was given by the Fawcett Library to the Australian government in 1998 and now hangs in Parliament House in Canberra.

As already noted there were delegates from other countries – such as Russia, Hungary and South Africa – in the procession, marching under the banner of the International Delegates – now held in The Women’s Library.

Reports suggest that the banner celebrating Marie Curie, then considered, at least by the women’s movement, as one of the foremost living scientists of the day, was carried by Frenchwomen. This is Mary Lowndes’ design for it.

After all the provincial societies came the Second Detachment – comprising doctors and other women graduates. I always thought it rather touching that the printed leaflets setting out the arrangements for the day specifically mentioned that there would be robing rooms available at 18 & 19 Buckingham St, just off the Strand, and at the Albert Hall to allow some privacy for the arranging of academic dress.

This group clearly impressed the Times. Their reporter wrote ‘Next marched the women doctors, in caps and gowns, followed by the lady graduates of the Universities of the UK, most of whom were also in academic dress. A brave show they made’.

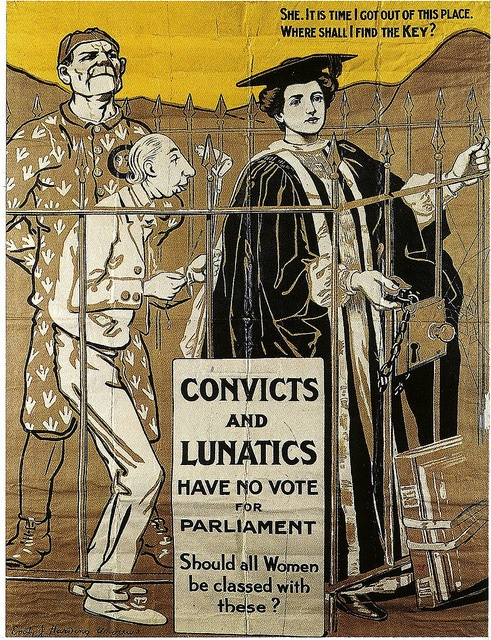

The fact that women were now being granted academic degrees by many of Britain’s universities was often used in other propaganda material – such as this poster designed by Emily Harding Andrews. (For more information about this artist see here.)

The fact that women were now being granted academic degrees by many of Britain’s universities was often used in other propaganda material – such as this poster designed by Emily Harding Andrews. (For more information about this artist see here.)

The intention was, of course, to emphasise women’s suitability for citizenship – particularly when contrasted with those whom they considered less worthy examples of the male of the species.

The Liverpool Post and Mercury reported that ‘One of the most beautiful banners was the doctors’; it was of rich white silk, with the word ‘Medicine’ in gold letters across the top, a silver serpent embroidered in the centre, and a border of palest green on which were worked the rose, shamrock, and thistle.’ The banner is now missing – but, quite by accident, I did come across a photograph of it in one of the Women Library’s archival holdings [Vera Holme album 7VJH/5/2/14].

The leading women doctors of the day – Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her sister-in-law, Mary Marshall, together with Flora Murray, Elizabeth Knight and Elizabeth Wilkes were among those walking in this section.

The doctors carried banners commemorating Elizabeth Blackwell, the first British woman to qualify as a doctor – although she had had to do so in the US. This banner is now held in the Women’s Library collection. The letters and the symbol are appliquéd. The symbolism is interesting. Instead of the rod of Asclepius (a snake entwined around rod – the symbol of the authority of medicine) here it is entwined around a lamp. The lamp was associated with the light of knowledge and might also be a version of the cup of Hygiea – the daughter of Asclepius – who was celebrated in her own right as a giver of health.

Another banner commemorates Edith Pechey Phipson, who had been a member of the first small group of women to qualify as doctors after Elizabeth Garrett. In 1906 she had represented Leeds at the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance conference at Copenhagen and had been one of the leaders of the Mud March in February 1907. She had died just a couple of months before, on 14 April 1908, and this banner was obviously intended as a special tribute. Perhaps we could date its manufacture to the preceding two months. It survives in the Women’s Library collection.

The profession of Education was represented by a specific banner. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph helpfully described it, reporting that ‘Miss Philippa Fawcett has presented the education banner, with its device of an owl and a small boy climbing the ladder of learning’. It has, however, disappeared

But that carried by the Graduates of the University of London – designed by Mary Lowndes – is now in the Museum of London collection.

Cambridge was represented by a particularly beautiful banner, now on permanent display in Newnham College. As a newspaper reported, ‘’The alumnae of Cambridge University, a detachment nearly 400 strong, were headed by the gorgeous banner of light blue silk which has been designed for the occasion,’ It was noted that these women didn’t wear academic dress – because the university still refused to grant them degrees – and would, of course, continue to do so for many more years. They did, however, as was reported, wear ‘on their shoulders favours of light blue ribbon’. Mary Lowndes had designed the banner and, as executed, the words ‘Better is Wisdom Than Weapons of War’ (a quotation from Ecclesiastes) were added below the Cambridge device. The pale blue silk had been given by Mrs Herringham from a quantity of materials that she had brought back from her travels in India.

After the Cambridge brigade marched business women. There were:

Shorthand Writers. The motto on their banner – designed by Mary Lowndes and held in the Women’s Library, is rather cleverly lifted from Robert Browning’s Asolando. And then came the Office Workers – their banner now, I think,held in the Museum of London. The Manchester Guardian described its device as, ‘Three black ravens bearing quills on a gold ground ‘

Next came a group of very active suffragists – the Women Writers’ Suffrage League -mustered under a striking banner that had already given rise to controversy,

This is the design in Mary Lowndes’ album. But the clerk to the Scriveners Company had written a letter, published in the Times on 12 June, saying that he had read that a banner bearing the arms of the Scriveners was to be carried and that any such banner certainly did not have the approval of his company. As it was, on the banner, as executed, WRITERS was substituted for SCRIVENERS. A letter from Mary Lowndes, published in the Times on 13 June, insisted that a black eagle upon a silver ground was certainly not the blazon of the Scriveners’ Company – but it would seem that the women had changed the associated wording at some point after the design was made.

The resulting banner, worked by Mrs Herringham, appliquéd in black and cream velvet, was given by Cicely Hamilton and Evelyn Sharp and was carried in the 1908 procession by them and by Sarah Grand, Beatrice Harraden and Elizabeth Robins. Cicely Hamilton wrote of the banner that it was ‘distinctive in black and white, impressive in velvet, and swelling, somewhat too proudly for comfort, in a gusty breeze’. This photograph was probably taken on a later occasion. In 1908 among the other women marching behind this banner were Mrs Thomas Hardy and Flora Annie Steele. This banner is now in the Museum of London collection.

The resulting banner, worked by Mrs Herringham, appliquéd in black and cream velvet, was given by Cicely Hamilton and Evelyn Sharp and was carried in the 1908 procession by them and by Sarah Grand, Beatrice Harraden and Elizabeth Robins. Cicely Hamilton wrote of the banner that it was ‘distinctive in black and white, impressive in velvet, and swelling, somewhat too proudly for comfort, in a gusty breeze’. This photograph was probably taken on a later occasion. In 1908 among the other women marching behind this banner were Mrs Thomas Hardy and Flora Annie Steele. This banner is now in the Museum of London collection.

Beside the banner advertising their own society, members of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League carried with them another series of banners now held here in the Women’s Library – banners bearing such names as Jane Austen and Charlotte and Emily Bronte. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph particularly noted this one – writing ‘Names of famous women are emblazoned on some of the banners and ‘Emily Bronte and Charlotte Bronte’ are two which Yorkshire women will be pleased to see on a simple green banner’. The addition of a white rose stresses the women’s Yorkshire connection.

Others commemorated Fanny Burney and Maria Edgeworth. The Museum of London also now holds another two from this series – commemorating Elizabeth Barrett Browning and George Eliot.

After the writers came banners glorifying Great Women of the Past. This was an obvious theme – and one that was to be used in later processions and stagings – such as Cicely Hamilton’s ‘Pageant of Great Women’.

These banners have survived well. Most were designed by Mary Lowndes and all were made by members of the ASL. Of them the Sunday Times wrote ‘The new banners of the movement are wonderful. Many of the banners were designed to celebrate the memory of the great women of all ages, from Vashti, Boadicea and Joan of Arc down to Mrs Browning, George Eliot and Queen Victoria. It was an attempt to represent pictorially the Valhalla of womanhood…As the procession moved away it presented a vista made up of wonderful colours, and it reminded one somehow of a picturesquely clad mediaeval army, marching out with waving gonfalons to certain victory.’

Reports indicate that a banner to Vashti led this element of the procession – but no trace of it remains.

Next came Boadicea. This is Mary Lowndes design – the actual banner is now in the Museum of London collection. Boadicea was a popular heroine of the moment – the bronze statue of her riding her chariot beside Westminster Bridge, right opposite Parliament, had been erected just six years previously, in 1902. In December 1906 each guest at the banquet at the Savoy put on by the NUWSS for released WSPU prisoners had been given what was described as ‘an emblematic picture of Queen Boadicea driving in a chariot, carrying a banner with the message “Votes for Women”‘. And by the autumn of 1908 the WSPU was selling in its shops ‘Boadicea’ brooches.

Joan of Arc was another great heroine of the suffrage movement and the idea of the warrior maiden with God on her side was invoked by both the constitutional and militant societies. Joan’s own banner was loved by her ’40 times better than her sword’, wrote Mrs Fawcett in a short biographical essay on Joan published by the NUWSS. The title page of this biographical pamphlet carries the same emblem of the crown and the crossed swords as appears here on the banner. The motto is, of course, Joan’s own.

In 1909 Elsie Howey, a WSPU activist, dressed as Joan and rode on horseback to greet Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence on her release from prison. You can see a photograph of Elsie in that week’s issue of Votes for Women. In 1909 a Jeanne d’Arc Suffrage League was formed in New York and on 3 June 1913 Emily Wilding Davison is reputed to have stood before the statue of Joan that took pride of place at that year’s WSPU summer fair -before setting off for Epsom and martyrdom. The statue had Joan’s words inscribed around the base – ‘Fight On, and God Will Give Victory’ and these were the words emblazoned on a banner carried at Emily’s funeral 11 days later. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in 1912 the Catholic Women’s Suffrage League’s banner, designed by Edith Craig, had St Joan as its motif and a few years later the society actually renamed itself the St Joan’s Social and Political Alliance. And, it was a version of Joan, uttering the words ‘At Last’, that the NUWSS used to greet the eventual attainment of partial suffrage in 1918. Images of Joan are to be found in the work of many women artists associated with the suffrage movement – Annie Swynnerton and Ernestine Mills spring to mind.

St Catherine of Siena, another woman visionary who combined piety with political involvement, also merited a banner Josephine Butler had written a biography of St Catherine in 1878. The banner was probably designed by Mary Lowndes and is held in the Women’s Library. Siena’s colours are black and white and the lily is symbolically associated with St Catherine

St Teresa’s banner, again designed by Mary Lowndes, is now in Museum of London. She featured also in Cicely Hamilton’s Pageant of Great Women – as the only woman on whom the title ‘Doctor of the Church’ has ever been conferred.

The banner to a Scottish heroine, Black Agnes of Dunbar – is now in the collection of the Museum of Scotland in Chambers St, Edinburgh. Of it the Daily Telegraph wrote ‘ There was one flag which attracted much attention. It was carried in front of the Dunfermline deputation. On a yellow ground was the representation of a portcullis, and beneath the large letters “Black Agnes of Dunbar” were the lines reminiscent of the defence of Dunbar castle by the Countess of March nearly 6 centuries ago: “Came they early, came they late, They found Black Agnes at the gate”. The banner perhaps should be placed earlier – with the provincial societies – but it fits well here – alongside the banner to

Katherine Bar-Lass – Katherine Douglas – who tried to save King James I by putting her arm in place of a missing locking bar in a door. This event took place in Perth and it may be that this banner heralded the deputation from that town. The banner is now held in the Women’s Library collection.

There is no difficulty in explaining why Queen Elizabeth I should be commemorated among the Great Women with a magnificent banner. Indeed the queen was something of a favourite of Millicent Fawcett who, in August 1928, unveiled an ancient statue of the queen at St Dunstans in the West, Fleet Street, having worked with a campaign for its restoration. She even left money to ensure its upkeep. (For more about Millicent Fawcett and the statue of Queen Elizabeth see here.)

Millicent Fawcett had also championed Mary Wollstonecraft, whose reputation during the 19th century had never recovered from William Godwin’s memoir of her. Mrs Fawcett wrote a preface to an edition of Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1891, the first for 40 years. Mary Wollstonecraft’s banner is held in the Women’s Library.

As is the rich and beautiful banner is to the astronomer Caroline Herschel, the discoverer of five new comets. Lady Caroline Gordon, the very elderly grand-daughter of Caroline’s brother, Sir William Herschel, had a letter published in the Times of 12 June 1908. She wrote ‘I observe that in the woman’s suffrage procession tomorrow it is intended to carry banners bearing, among others, the names of Caroline Herschel and Mary Somerville, thereby associating these honoured names with the cause. A more unfounded inference could hardly be drawn. My great aunt, Miss Herschel, never ceased during her very long life to insist on the fact that she was only her brother’s amanuensis, and it was the glory of her life to feel that she had a real work to do and a province all her own, which was to help him in his arduous labours, and keep worries and troubles from him. She sank herself and her own great and valuable discoveries entirely. All who knew Mrs Somerville (and I was one of them) can testify to the great humility and simplicity of mind which were her characteristics. Her work was done for work’s sake, not for any wish to show what a woman could do. Such a thought would be utterly distasteful to her. To think that the names of these two noble women should be paraded through the streets of London in such a cause as woman’s suffrage is very bitter to all of us who love and revere their memories’.

Here is Mary Somerville’s banner. On 15 June Millicent Fawcett replied in the Times (her letter was dated 13 June – she had taken the time and trouble on such a busy day to write it).‘May I be permitted to point out that suffragists believe that the names of “distinguished women who did noble work in their sphere” are in themselves an argument against relegating a whole sex to a lower political status than felons and idiots? This is quite independent of whether the particular distinguished women named on the banners were suffragists or not. The names of Joan of Arc and Queen Elizabeth are found on the banners. The inference is surely clear. Lady Gordon affirms that her distinguished great-aunt Caroline Herschel was no suffragist. No one in their senses would expect a German lady born in 1750 to be one. Her services to astronomy were well recognized in the scientific world of her time. Her extreme modesty gave an additional luster to her name. Her chief work in astronomy was undertaken and carried through after her brother’s death and it was for this that she was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828. Mrs Somerville’s case is quite different. She belongs to our own nation and to the modern world, and was an ardent suffragist. She wrote expressing her deep gratitude to JS Mill for raising the question of women’s suffrage in parliament. She signed parliamentary petitions again and again in favour of removing the political disabilities of women, and was a member from its foundation to the date of her death in 1872 of the London Society for promoting the movement.’

Mary Kingsley, the traveller and explorer, was another heroine who merited a banner, although no supporter of women’s suffrage.

The Elizabeth Fry banner was designed by Mary Lowndes and was, I know, donated by a Miss Prothero. Although I don’t know exactly who Miss Prothero was, I am sure there must be a Quaker connection. It is now in Museum of London collection. Josephine Butler had died only 18 months before the procession. Her banner is now held in the Women’s Library.

Lydia Becker was very suitably represented by the pick and shovel of the pioneer. She had worked for over 20 years at the suffrage coal face – organizing, devising, interviewing, writing, lobbying and speaking. Her banner, unfortunately, is one of the few of this series that is now missing, another being that commemorating a very Victorian heroine, Grace Darling, a figure who features in many of the suffrage pageants..

The final banner in the sequence, a rich riot of colour commemorating other pioneers is held safely in the Women’s Library collection. The first four it lists are particularly related to Bristol.

After the Pioneers came the artists, the musicians and the actors. The beautiful banner made for the Artists’ Suffrage League itself is now in the Museum of London. Christiana Herringham helped to embroider it – with its motto ‘Alliance Not Defiance’, supplying silks for it that were among those she had brought back from India.

A banner bearing the heading ‘Music’, designed by Mary Lowndes, was given by ‘Mrs Dawes and worked by her and her daughters’ – but has now disappeared.

Jenny Lind’s banner, was carried in the procession by her daughter, Mrs Raymond Maude, who was described as ‘a striking figure in green and white, with a Tuscan hat’ [ I think a ‘Tuscan hat’ was a wide-brimmed straw hat]. The banner was designed by Mary Lowndes and is now held in the Women’s Library collecction.

Artists were represented by Mary Moser, who, with Anglica Kaufmann, was the first woman to be elected to the Royal Academy. She was renowned as a flower painter –and was paid the enormous sum of £900 for the decorations, which notably featured roses, of a room she painted at Frogmore for Queen Charlotte. These decorations can still be seen – as can this banner, now in the Women’s Library collection.

Angelica Kauffman also had a banner– but it is now lost.

Sarah Siddons’ banner which was carried in this section of the procession is now held in the Museum of London.

As is the banner to ‘Victoria, Queen and Mother’ – which was carried in the procession of Maud Arncliffe –Sennet – who, I must say, I always think of as something of a self-publicist – an opinion not actually belied by finding that she had had, or caused to have had, a photograph taken of herself on the day, holding the banner – there is a copy of that postcard, too, in the Museum of London collection.

After the banners commemorating the heroines of the past came one celebrating Florence Nightingale – then still alive – a heroine in her own lifetime. The banner was carried by a contingent of hospital nurses, marching in their uniforms. The Daily Express reported that ‘The Florence Nightingale banner received the greatest notice. It bore the word “Crimea”, and at the sight old soldiers saluted and bared their heads.’

As an added gloss I might mention that in June 1908 a bill to allow for the registration of qualified nurses was before parliament –it passed its second reading on 6 July and many leading suffragists, such as Millicent Fawcett, Isabella Ford, and Hertha Ayrton had signed a letter to the Times in support of the bill.

There followed also groups of women farmers and gymnasts, each with their own banner. Women gardeners carried a banner worked in earthy colours – green and brown, with the device of a rake and a spade. All these now, unfortunately, are lost.

After the nurses came the Homemakers – we can see the banner here – although the photograph was probably taken on another occasion. As the Sheffield Daily Telegraph put it, ‘The sacred fire of the domestic hearth is pictured by the home workers, who ‘remember their homeless sisters, and demand the vote’. Another newspaper report describes this contingent as comprising ‘Housekeepers, cooks, kitchenmaids and general servants’ – and laments that they were not wearing their uniforms. Note also in the photograph the banners for Marylebone, Camberwell and North Kensington.

After the home makers – came working women – working women of all sorts, carrying a variety of banners. These would appear to be plainer than the Artists’ Suffrage League ones and were locally made.

After the working women came the Liberal women, who, as one newspaper reported, bore a banner announcing that they demanded the vote…as well as Conservatives, who were led by Lady Knightley of Fawsley, and by Fabians, whose banner, had been designed by May Morris, with the motto ‘Equal Opportunities for Men and Women.’.

Then came members of the Women’s Freedom League – the press particularly mentioned its leader, Mrs Despard, together with Teresa Billington-Greig and young Irene Miller, The WFL banner was black and yellow, figured with a device of Holloway, where many of its members had recently been imprisoned, and with the inscription ‘Stone walls do not a prison make’. The WSPU, although not invited to take part, did supply a banner under their insignia – declaring ‘Salutation and Greeting. Success to the Cause’.

Finally, closing the long procession, came the hosts – London Society of the NUWSS. This is the design for the society’s banner. The banner itself is now in the Museum of London collection

This section included detachments from the various London boroughs – such as Camberwell, Croydon, Chelsea and Holborn. The Daily Telegraph tells us that ‘The Holborn deputation was headed by a picture of some of the ancient shops opposite Holborn Bars, and the words “The old order changeth”. Enfield’s banner survives and is now in the Museum of London – but we have no design for it so it probably was not one of Mary Lowndes’ creations.

This design for Wandsworth in the Mary Lowndes album has the initials ‘A.G.’ at the side – and I did wonder if these could possibly refer to Agnes Garrett – sister of Millicent Fawcett. It is by no means impossible that she was involved in the banner-making – given that her professional career had been devoted to the designing and making of furnishings. But I don’t know.

Wimbledon was a very committed suffrage stronghold – both of the NUWSS and of the WSPU – and both groups featured the windmill on their banners. Of the NUWSS one only this design survives – but the Women’s Library does hold the actual WSPU banner.

All in all the procession, which was accompanied by 15 brass and silver bands, – one reporter particularly mentioned that hearing the Marseilles being played in these circumstances quite brought a tear to his eye – and the Albert Hall rally that followed, were both deemed a great success. Afterwards a decision was made by the NUWSS to keep the banners together and tour them. It was realised that ‘undoubtedly we have here an opportunity of presenting an artistic feast of the first order under circumstances that make it in itself, and in all attendant conditions that may be grouped around it, a unique act of propaganda.’

They lent out the banners to the local societies, charging £3 10s for all 76 banners or £2 for half the number –with the express proviso that they were not to be used for what was termed ‘outdoor work’..

In 1908 exhibitions of the banners were held at Manchester, Cambridge, Birmingham, Liverpool, Camberwell, Glasgow and Edinburgh. Lady Frances Balfour opened those last two – and performed the honours again at Brighton in January and Fulham in March 1909. We can be sure that the local societies made the most of these occasions. I know that when the banner exhibition was held in December 1908 at the Glasgow Fine Art Institute it was accompanied by tea, a small string band and a pianola. The Society clearly expected a reasonable attendance, finding it worthwhile to buy in – to sell to visitors – 200 copies of the pamphlet describing the banners.

Thus not only did the banners allow suffragists to rally round as they were paraded through the streets but they also provided a focus for further conscious and fund-raising efforts that neatly combined a forceful political message with what been described, very eloquently, as the power of ‘the subversive stitch’.

P.S.

Kate Frye was a banner bearer – for North Kensington – in this procession – and you can read all about her experience on the day here.

Copyright

#1 by artandarchitecturemainly on November 27, 2014 - 5:41 am

Normally one expects political banners to be ephemeral pieces of protest art, designed to last as long as the marchers required. But the Dora Meeson banner was lovely. She designed and painted the banner which was first used in a suffragette parade in 1908 and subsequently at later demonstrations in London – so it lasted and lasted.

I am delighted the banner was later presented to the women of Australia as a Bicentenary gift in 1988 and is on now on permanent display in Parliament House, Canberra. Perfect placement for a proud moment in Australian feminist history!

thanks for the link

Hels

http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com.au/2013/11/dora-meeson-australian-expat-artist-in.html

#2 by Amy Binns on June 30, 2015 - 1:44 pm

What a lovely article, I plan to use it in my own research comparing the use of pageants with today’s Cosmo Ultimate Women Awards etc.

#3 by womanandhersphere on July 1, 2015 - 12:56 pm

Amy – Many thanks for taking the trouble to comment. Glad to be of use! Elizabeth

#4 by Anna Baker on November 7, 2016 - 10:43 pm

This is a great article! And I would like to use it for my own project on feminist embroidery. Do you have a bibliography that shows your sources? I’d like to use that James Douglas quotation from the Morning Leader, but I can’t find the original source. Thanks!

#5 by womanandhersphere on November 8, 2016 - 9:23 am

I am glad you enjoyed reading this piece… However, as it was, as you’ll see from the introduction, originally a talk to a ‘lay’ audience and not an academic article I didn’t compile a bibliography for it. I think, though, the James Douglas quote comes from his book ‘Adventures in London’. There is also a quote from his Morning Leader piece in the issue of Votes for Women for 23 June 1911. If you use material from my article I’d be grateful if you could acknowledge the source. Many thanks, Elizabeth

#6 by Georgina Gittins on July 16, 2019 - 4:29 pm

Hello, I have enjoyed reading your article so much. It gives you a real sense of the occasion, helping you to imagine the strength of feeling as well as the spectacle itself.

Do you know anything about the banner of the West Cheshire, West Lancashire and North Wales contingent? There’s a picture of it here. Do you know the branch’s position in the march?

https://vads.ac.uk/x-large.php?uid=78635&sos=0

I believe that women from my home town, Wrexham would have marched with this banner as they were part of this branch from 1911 – 1918.

#7 by womanandhersphere on July 17, 2019 - 11:45 am

Georgina – I’m afraid I don’t know anything about that banner…other than the design. It is, of course, later than the banners I write about in the article…but may well have been carried in the 1913 NUWSS suffrage Pilgrimage. That might be a line of enquiry fr you to follow.

Best wishes, Elizabeth

#8 by Georgina Gittins on July 17, 2019 - 2:53 pm

Thank you – if I ever find out I’ll let you know! The branch had delegates on the 1911 and 1913 marches but I’ve not yet found any details; just evidence from newspaper articles that they were present.