Suffrage Stories: Suffragettes And Their Dress

Posted by womanandhersphere in Suffrage Stories on May 6, 2021

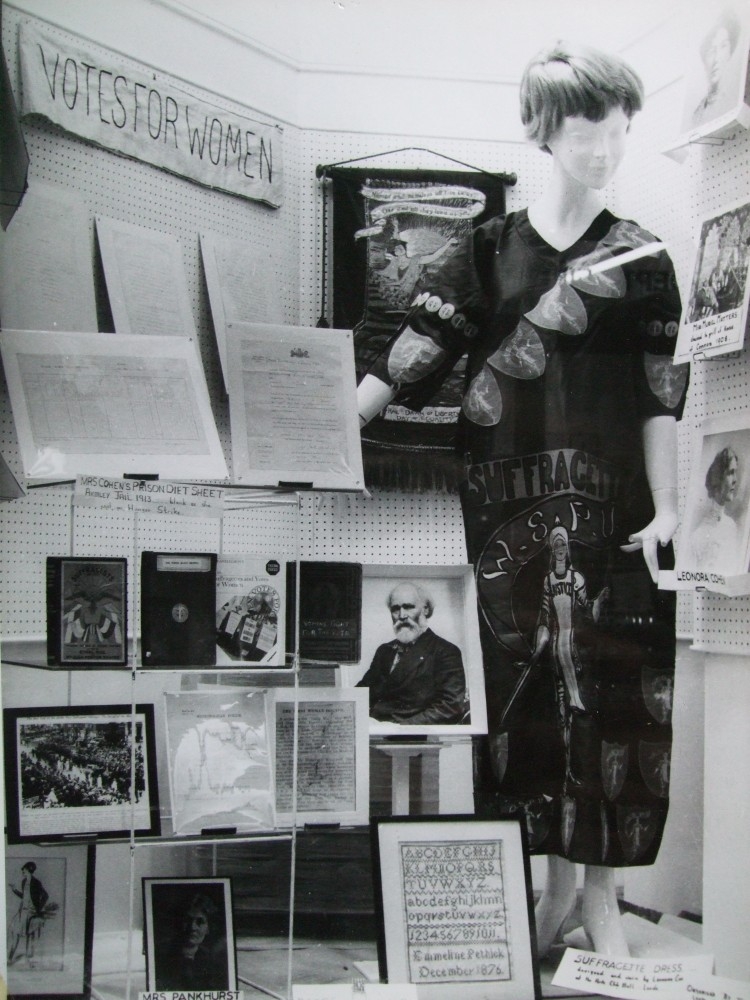

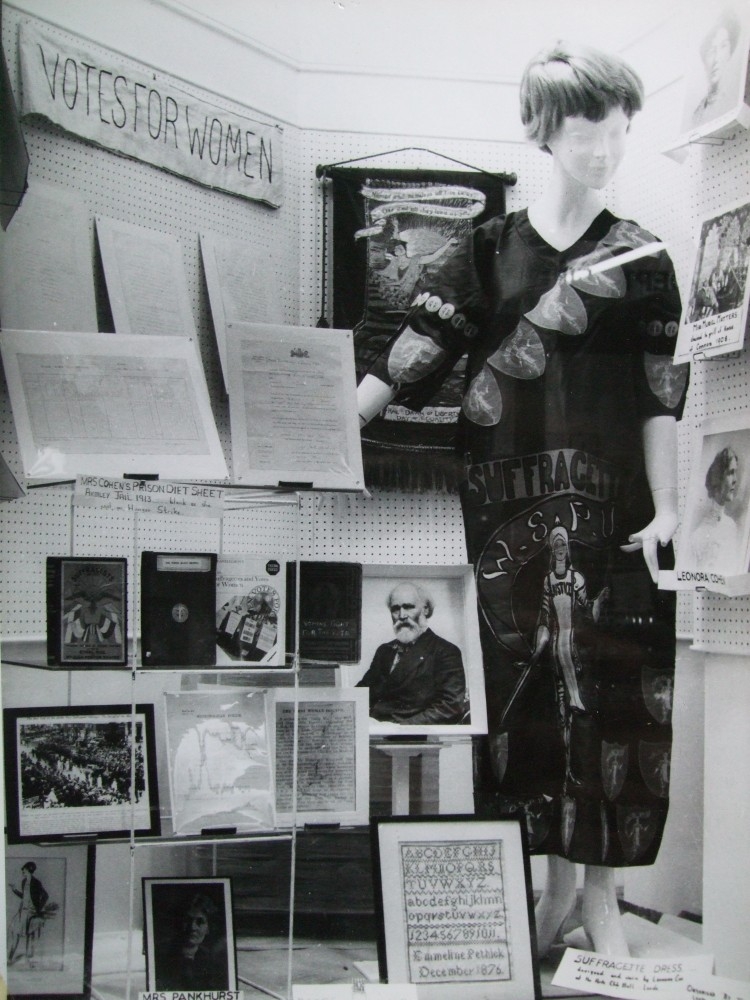

The apotheosis of suffragette dress

The term ‘suffragette’ was invented in 1906 by the Daily Mail, as a belittling epithet, and was then adopted as a badge of honour by the women it sought to demean. These women – the suffragettes –campaigning for the parliamentary vote – were members of what are termed the ‘militant’ suffrage society – the Women’s Social and Political Union, led by Mrs Pankhurst and her daughters.

It would be possible to approach the subject of suffragettes and their dress chronologically because during what we think of as the Edwardian years, that is from 1901 to 1914, women’s dress did alter decisively, from the curvy, rather fussy outline, topped by a large hat, of the early years to the more tailored look in the year or so before the outbreak of war. It could be argued that this was not unconnected to the growing importance and popularity of the campaign for ‘votes for women’. However, I thought it would be interesting to approach the topic from a different angle – to see whether the suffragettes used dress as a weapon in their campaign and, if so, why and how.

The suffragettes were by no means the first women in Britain to campaign for the right to vote in parliamentary elections. That campaign had begun 40 years earlier, in 1866, when John Stuart Mill, then MP for Westminster, presented a petition to the House of Commons asking for the vote for women on the same terms as it was granted to men. Why were women barred from voting? The one reason – unarguable in its unreasonableness – was simply that in the mid 19th c the act of voting was gendered male – just as the army, the navy and the church were male. The ballot was not secret, votes were bought with beer, and the hustings were notorious for scenes of drunken brawling. Women who claimed a right to enter this world were transgressing the gender divide. In consequence, such women were either regarded, negatively, as insufficiently womanly – the jibe was that they must want the vote to make up for their lack of charms – or as positively masculine – as women aping men. Either way the popular verdict was that these ‘women’s righters’ were embarrassments – figures of fun.

As dress may be taken as the outer signifier of inner thought, the appearance of women who campaigned for the vote was always a matter to be given serious consideration.– both during the 19th century and then during the Edwardian campaign.

This is Punch’s view of the presentation of that first petition. The representation of the women – the ‘persons’ – whom Mill is leading – does reflect something in demeanour and dress of the women who organised the petition. They were, on the whole, self-confident, young middle-class women – the wearers of muffs and fashionable bonnets. The more elderly woman with glasses represented the earnestness of the movement – while the image of the old woman with the umbrella – as depicted, a member of a class of women who would have no hope of gaining the vote, which was based on property holding – was the caricature that was to feature in both 19th and 20th c popular representations of the suffrage movement, particularly on comic postcards in the Edwardian period.

The petition had been put together very quickly – women went round their friends, relations and neighbours asking for signatures.Here are two young women who did just that – in Aldeburgh in Suffolk. They are Millicent Garrett, sitting down, and her sister, Agnes. As you will note they are entirely conventionally attired as young women of the 1860s. Both were to be involved in the suffrage campaign all their long lives – Millicent Garrett, as Mrs Millicent Fawcett, was to negotiate women to the ballot box in 1918.

Millicent and Agnes very much looked up to their elder sister, Elizabeth, who, in spite of many difficulties put in her way, had in 1866 managed to become the first woman to qualify in Britain as a doctor. She was one of those in London who were organizing the suffrage petition. Again, all her life she made no particular statement about her looks – but dressed in such a way that, within the bounds of conventional fashion, she could carry out her work as a doctor in the hospital she founded and as lecturer and eventually dean of the London School of Medicine for Women. Like Millicent, she was, at this time, very much of the view that women would get the vote by proving themselves worthy – not by upsetting the establishment. One aspect of this was that from the very beginning of the campaign it was recognised that women were more likely to be taken seriously – or at least, not dismissed out of hand – if in outward appearance – in dress and demeanour – they conformed to the general ‘look’ expected of women – that is, if they placed themselves firmly on the female side of the gender divide and avoided looking either unwomanly or mannish. For instance, when in 1870 public suffrage meetings was being planned in London, Elizabeth Garrett, who was something of a cynic, suggested that it would be a good idea to make sure that only pretty, well-dressed women filled the front row.

At a time when it was still exceptional for a well-brought up woman to speak on a public platform, suffrage speakers quickly made their mark and by 1874 Punch had already made up its mind on the subject of the dress of a typical suffrage campaigner. Here the cartoonist has elected to depict her as positively masculine. Now, just such a woman as Punch was referring to – a famous champion of women’s rights, although by all accounts very much more attractive in the flesh – was Rhoda Garrett – who was not only the cousin of Agnes, Elizabeth and Millicent, but also the partner, both in an interior design business and in life, of Agnes.

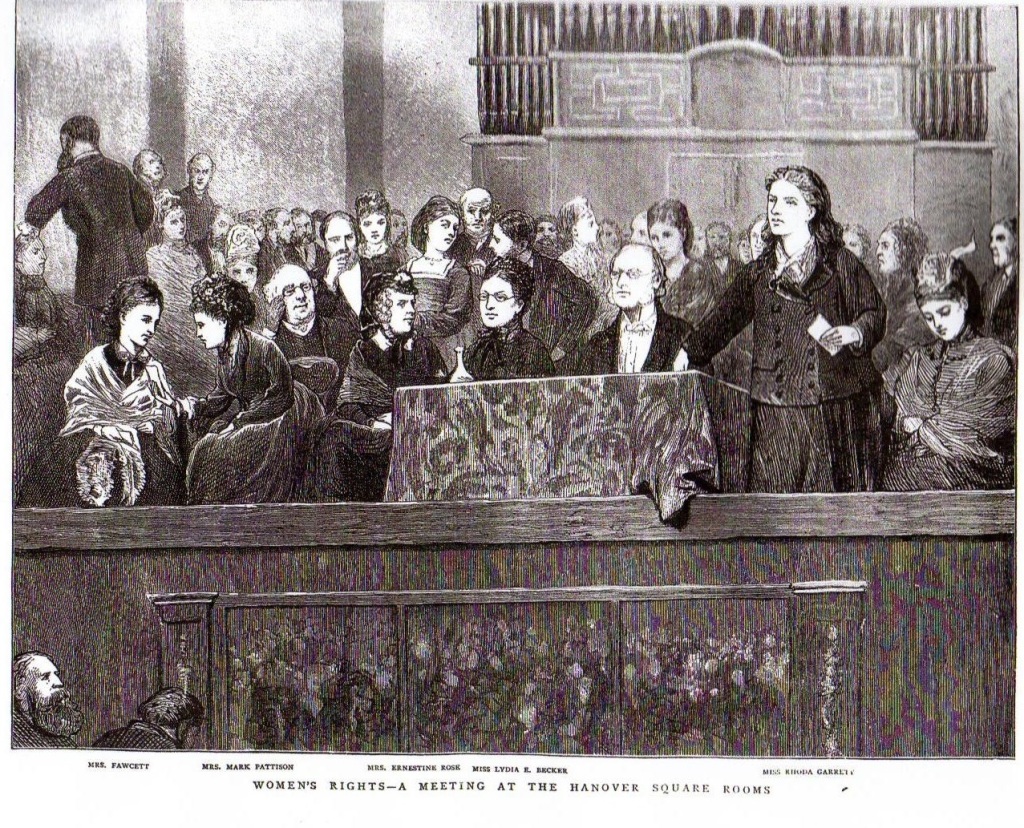

An engraving of Rhoda speaking at a London public meeting in 1872, shows her wearing an outfit such as that in the Punch cartoon – a loose jacket and skirt. She is hatless and her hair is loose and she certainly doesn’t look to be corseted. Rhoda was on the radical wing of the suffrage movement – her attire reflecting her freer approach She was prepared, for instance, openly to support the campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts. Millicent Fawcett, on the other hand, believed that it was dangerous to the suffrage cause to mix it in the public mind with any mention of prostitution. You can see Millicent here on the left, with hair braided, shawl draped.

Rhoda Garrett died in 1882 – when barely 40 – and is now little remembered. If she had lived she might well have made a very interesting figurehead for the suffrage movement – both in terms of the substance of her speeches and in her idiosyncratic style of dress.

But by the beginning of the 20th century, despite the hundreds and hundreds of meetings, petitions presented and bills debated, women were still denied the vote – even though by then the act of voting only meant, as it does now, putting a piece of paper into a box, the electoral hustings no longer involved hard drinking and unseemly brawls and women had already won the right to vote for many local government bodies.

In October 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst decided to form her own pressure group – the Women’s Social and Political Union – to make a determined effort to move the campaign forward. She had been involved with the suffrage movement since the 1880s when living with her husband and children in Manchester. Despite spending some years moving in London Arts and Crafts circles, Emmeline always remained more a figure rendered by Tissot than Burne-Jones. She preferred Parisian modes to Pre-Raphaelite drapery. By the time she founded the WSPU she was a widow, back living in Manchester. It took a couple of years to gather steam and it was when the WSPU began to make itself seen and heard in London that the term ‘suffragette’ was coined. By 1906 the difference between the suffragettes and the original campaigners – the ‘suffragists’ – had become clear.

The WSPU were prepared to demonstrate in an increasingly militant fashion, while the suffragists, members of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies – known as the NUWSS – led by Millicent Fawcett, remained ‘constitutional’ – that is they would not contemplate breaking any aspect of the law. Even when under arrest Mrs Pankhurst contrived to look elegant and womanly.

Emmeline Pankhurst was soon joined in the WSPU by her eldest daughter, Christabel. The photograph above dates from c 1908 – her dress is rather more ‘artistic’ than her mother’s – the brooch may have been designed by C.R. Ashbee.

In the Vanity Fair ‘Spy’ cartoon from a couple of years later she appears to be wearing the same gown – which we can now see is green, a favourite colour. Grace Roe, who was to become a life-long friend, has left a description of the first time she saw Emmeline and Christabel speaking – at a WSPU rally in Hyde Park in 1908. Although she was interested in the women’s suffrage movement she had been put off by the press reports and was afraid that Emmeline and Christabel might be ‘unwomanly women’. However, she was delighted to discover that, on the contrary, ‘There was Mrs Pankhurst, this magnificent figure, like a queen’ and Christabel who ‘had taken off her bonnet and cloak, and was wearing a green tussore silk dress. She was very graceful, had lovely hands and a wonderful way of using them.’

And here is Christabel again, photographed at the Women’s Exhibition – a WSPU bazaar that was both fund and image-raising – held in Knightsbridge in 1909. And that is a hat that is intended to disarm – to secure her as a ‘womanly woman ‘ and disprove any association with the Shrieking Sisterhood. The photographs of Emmeline and Christabel– as were many others of the leaders – were reproduced on postcards, which were sold by the WSPU. By doing so they not only advertised that they conformed to accepted views of womanhood, but raised money in the process.

Emmeline Pankhurst’s second daughter, Sylvia, was an artist, and had trained at Royal College of Art. She eventually broke away from Emmeline and Christabel to pursue the campaign for the vote from a base among the working women of the East End. She always appears conventionally, if carelessly, dressed and in 1911 the WSPU newspaper, Votes for Women, characterised her as too busy to be ‘bothered about her hair, or the hang of her skirt.’ Another suffragette described her as dressing ‘like a Quakeress in sober browns and greys’. But when the occasion demanded even she, radical that she was, was prepared to make an effort. During an American tour in 1911 a reporter in Des Moines described her arriving at a suffrage meeting, a ‘pink-cheeked slender girl clad in a trailing gown of creamy silk, [who] dropped modestly into a seat on the platform and raised her blue eyes to meet the hundreds in the audience.’

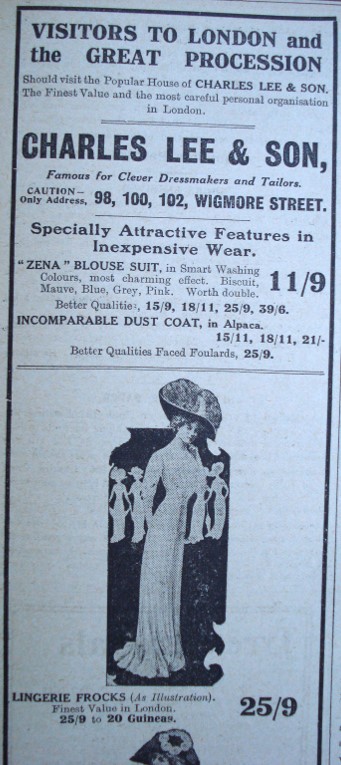

Emmeline Pethick Lawrence and her husband, Frederick, were wealthy philanthropists – working philanthropists- who brought both money and organisational skill to the WSPU, joining the Pankhursts as its leaders. Mrs Pethick Lawrence was particularly disturbed by the exploitation of girls working in the London dress trade and in the early years of the 20th century founded a club for them. In fact, in the mid-19th century, right at the very beginning of the suffrage campaign, it had been concern for what were then termed ‘needlewomen’ that had dominated much of the discourse. Although, of course, such women would not be emancipated under the terms for which the vote was being demanded, middle-class women thought that if they had the vote they would be able to improve the lives of their working-class sisters. The irony of women slaving to provide new fashions for other women was not lost on the campaigners. Emmeline Pethick Lawrence set up not only a club, but also a tailoring co-operative – ‘Maison Esperance’ – to free at least a few girls from exploitation. It was based first in Great Portland Street and then in Wigmore Street. As you see, Emmeline Pethick Lawrence favoured rather loose, flowing garments – richly embroidered, tasselled – floating scarves. I think they qualify as artistic; she was certainly rather fey and spiritual.

These women were, of course, all middle-class, but the WSPU also had its working-class icons – the most important of whom was Annie Kenney. Until swept up by the Pankhursts, she had been a mill girl in Lancashire – and for many of her early public appearances she was dressed in shawl and clogs – for effect, I may say. That is not how she would have chosen to dress. In the photograph on the left she appears in the mill girl guise, alongside Mrs Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy, who had been one of the earliest of the suffrage campaigners. Mrs Elmy was impoverished – what money she had was spent on campaigning – and totally unworldly – her ringletted hair was styled as it had been in her youth – but was well aware that it would never do, as she said, to ‘look a scarecrow’ when appearing in public. So friends united in providing her with a new gown when necessary, ensuring that her appearance was commensurate with her importance in the movement.

Rather than shawl and clogs Annie Kenney much preferred the type of garments that those with whom she now associated wore – such as she wears in the above photo. Thus, in December 1906, for a dinner given at the Savoy by Mrs Fawcett and the NUWSS to celebrate the release of WSPU prisoners, Annie recorded that ‘Mrs Lawrence bought me a very pretty green silk Liberty dress for the occasion, and I wore a piece of real lace. I was so pleased with both.’

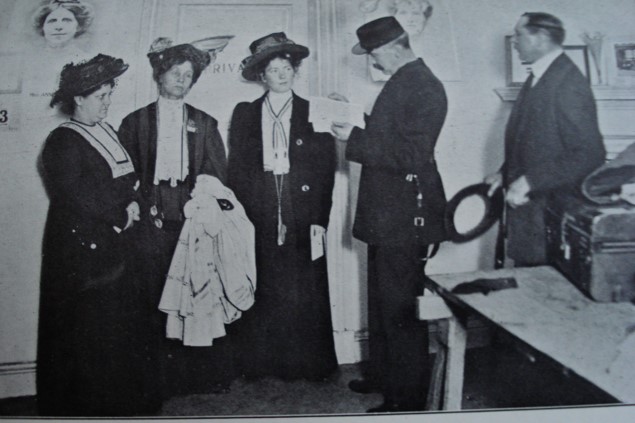

For by the autumn of 1906 WSPU militancy now involved arrest and imprisonment. This photograph was taken a couple of years later – at the WSPU office in Clement’s Inn in the Strand and shows the leaders being arrested by Inspector Jarvis of the Yard. From this we can get a good indication of their normal daywear. From left to right they are Mrs Flora Drummond – Mrs Pankhurst – and Christabel. Annie Kenney looks down from the poster on wall

Pageantry

But alongside militancy that led to arrest was militancy that merely involved making a peaceful, public demonstration. Although the WSPU’s first London march in 1906 comprised women from the East End, many carrying their babies, the WSPU did not pursue its involvement with working-class women. Wealthier women were more able to contribute not only funds but a more glamorous presence on the streets. It was they who were mustered for the spectacles of pageantry that the WSPU in successive years mounted in London – and in provincial cities. These displays gave the photographers material to record. Both still and moving cameras were used – for newsreel of the occasions was shown in cinemas.

The WSPU staged the first of their major pageants in Hyde Park in June 1908. It was estimated that a quarter of a million people attended. In order to make as dramatic an effect as possible Mrs Pethick Lawrence suggested that women should wear white – and, of course, – as we see here – did so herself. .One suffragette, Jessie Stephenson, has left a description of how ‘my milliner and dressmaker took endless pains with my attire. A white lacy muslin dress, white shoes and stockings and gloves and, like an order, across the breast, the broad band in purple, white and green emblazoned “Votes for Women”, a white shady hat trimmed with white’. The mother of another WSPU member, Mary Blathwayt from Bath, recorded in her diary that Mary was dressed ‘in white muslin with the scarf crosswise over her shoulder’.– as the woman on the left wearing .

The scarf was a new piece of merchandise – a motoring scarf in the new WSPU colours of purple, white and green – a combination devised by Emmeline Pethick Lawrence to represent the WSPU brand – and with which the WSPU is still associated. The colours were used on programmes, rosettes, flags and banners and on the sashes the women draped across themselves.

Even Mrs Wolstenholme Elmy wore a sash, standing alongside Mrs Pankhurst. She has left us details of the bouquet she was given to carry –advertising the WSPU’s colours in a composition of ‘ferns, huge purple lilies and lily of the valley’.

The colours were not only employed in the course of the pageants. In Nov 1910 Christabel Pankhurst was one of the leaders of a deputation of all the women’s suffrage societies to Asquith and Lloyd George and for the occasion dressed in a coat with wide satin lapels in purple, white and green. The journalist Henry Nevinson commented in his diary that it was ‘fine – but a little overdone for the morning.’

In order to sell the merchandise, the local WSPU societies opened shops – taking short leases on high street properties, just as charity shops do today. This is the one run by the Putney society. They produced a wide-range of tempting goods – from board and card games, to ‘Votes for Women’ tea and soap and ‘Emmeline’ and ‘Christabel’ bags. The Pankhursts were the Alexa Chungs of their day. But one of the most popular type of merchandise was what might be loosely termed ‘jewellery’. This ranged from mass-produced badges to hand-wrought items. One WSPU diarist recorded that the local society ‘had taken a shop in the central part of the town, and decorated it beautifully with purple, white and green flags. On a counter I saw piles of leaflets, pamphlets and Suffragette literature, also very pretty little brooches in the colours, one of which I bought and intend always to wear’

The WSPU had very quickly developed the idea of creating such symbols to be worn to indicate support for their cause. Soon all the suffrage societies, ranging through the Women’s Freedom League, the Actresses’ Franchise League, the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, the NUWSS, the Men’s League and, as here, the Jewish League all had their own colours and badges.

Something of an irritating mythology has gathered around the concept of ‘suffragette jewellery’, fostered by dealers and auction houses who like to claim that any piece with stones approximating to the colours purple, white and green, must be of suffragette association. Although, at the height of the WSPU campaign, such pieces certainly were manufactured both by commercial and craft jewellers, it is now very difficult to identify them with any certainty as suffragette – amethysts, pearls and demantoid garnets or emeralds were very commonly used in Edwardian jewellery. We do know that some pieces were made with the WSPU in mind. For instance, in December 1909 Mappin and Webb issued a catalogue of ‘Suffragette jewellery’.

And this silver and enamel pendant using a design by Sylvia Pankhurst was certainly made and sold in WSPU shops. And in Votes for Women craft workers advertised jewellery made up in the colours and the numerous fund-raising bazaars provided ample opportunity for purchasing such items of jewellery associated with the movement.

We also know that one-off pieces of suffragette jewellery were made.In 1909 Ernestine Mills, an enameller who was a WSPU supporter, was commissioned by the Chelsea WSPU to make a pendant for one of their members on her release from prison. In silver enamel, it depicted the winged figure of Hope singing outside the prison bars and was held by a chain made up of purple, white and green stones. Above is a pendant made by ernestine Mills for an Irish suffragette.

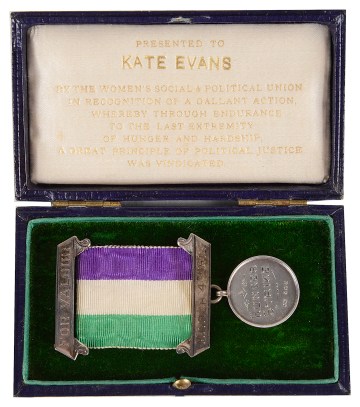

The symbolism of both jewellery and of military decoration is realized in a portrait of Flora Drummond, painted in 1936, that now hangs in the Scottish Portrait Gallery. She was a Scots woman living in Manchester who along with, or despite, her husband and young son, was swept into the WSPU in its very early days. As you can see, she took to it with a will –and was known as General Drummond. .For her portrait she wore a large pendant of purple, white and green stones alongside the WSPU equivalent of the Victoria Cross – the hunger-strike medal.

As you can see from this photo, held by the Museum of London, the WSPU by 1908 or so had, alongside its desire for its members to be seen as womanly women, begun to embrace a more military ethos. Uniform – or at least uniformity – were important elements when producing pageantry and processions – in creating a spectacle. Here we see a suffragette acting as a standard bearer You will note how like a uniform she has made her outfit – although all the individual pieces are, I imagine, conventional

For the major suffragette demonstration in Hyde Park in 1910 the WSPU paper,Votes for Women, asked those taking part to march eyes front, like a soldier and ‘to remember you are just a unit in a great whole’. Hints were also given on how to dress. ‘Don’t wear gowns that have to be held up. Don’t wear enormous hats that block the view. Do wear white if possible. Do in any case keep to the colours.’ .Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, who was probably responsible for this edict, took her own advice. She wore a lovely dress – with a hem that was perhaps weighted in someway, to bell out a little, clearing the ground. She wears a loose lacy long jacket over the dress – also white. Her hat may have been purple or green – although of course one cannot tell from the photograph – and is neat and close fitting. Her gloves are white and she carries a little bag – again probably in purple or green. Sylvia is holding one of the placards she had designed that were a feature of this procession –a convict’s arrow was superimposed on the House of Commons portcullis – symbolising the lengths that women were prepared to go to gain the vote. Christabel is in academic dress – she had graduated in 1906 with a first-class degree in law from Manchester University. In all the major processions graduates marched as a group – emphasising the fact that, although they had attained scholastic heights, they were still denied the vote.

Emily Wilding Davison is the other figure in academic dress in the Hyde Park photo and on a separate occasion sat for a studio photographer in academic dress – she had gained her degree in the 1890’s. The photograph can be dated to some time after 1908 by the fact that she is wearing a particular brooch – the WSPU Holloway badge – given to women who had been imprisoned. This was the photograph that the WSPU chose to publish in the press and on postcards after her death at the Derby in 1913 – the image chosen to reinforce the idea of intellectual achievement – of noble womanhood sacrificed.

In 1911, Britain having badefarewell to King Edward the previous year, prepared to celebrate the coronation of the new king. The suffragettes, in a spirit of truce, held back on their militant campaign to stage perhaps their most spectacular procession – and demonstrate, in mass, their womanliness.

For this procession the WSPU organized separate contingents representing different groups –their dress making specific statements.

This is the Indian contingent.

Nurses – who always received a warm welcome from bystanders as they marched past

Members of Cymric Suffrage Society – the welsh suffrage society – dressed in their regional costume

Cicely Hamilton, seen here (3rd from left) carrying the Women Writers Suffrage League banner, was very much a lady who favoured the tailor rather than the dressmaker. In her autobiography she wrote: ‘A curious characteristic of the militant suffragette movement was the importance it attached to dress and appearance, and its insistence on the feminine note. In the WSPU all suggestion of the masculine was carefully avoided, and the outfit of a militant setting forth to smash windows would probably include a picture hat.’

But be that as it may, there were some women who were able within the WSPU to adopt a role that allowed them to wear clothing more masculine than was otherwise acceptable. Here we see Vera – also known as Jack – Holme, the WSPU’s chauffeur. Involvement with the WSPU allowed her very much more scope to lead the kind of life she wanted – previously she had been an actress in the D’Oyly Carte. As Mrs Pankhurst’s chauffeur she wore a striking uniform in the WSPU colours, with a smart peaked cap decorated with her RAC badge of efficiency – atop her decidedly short hair.

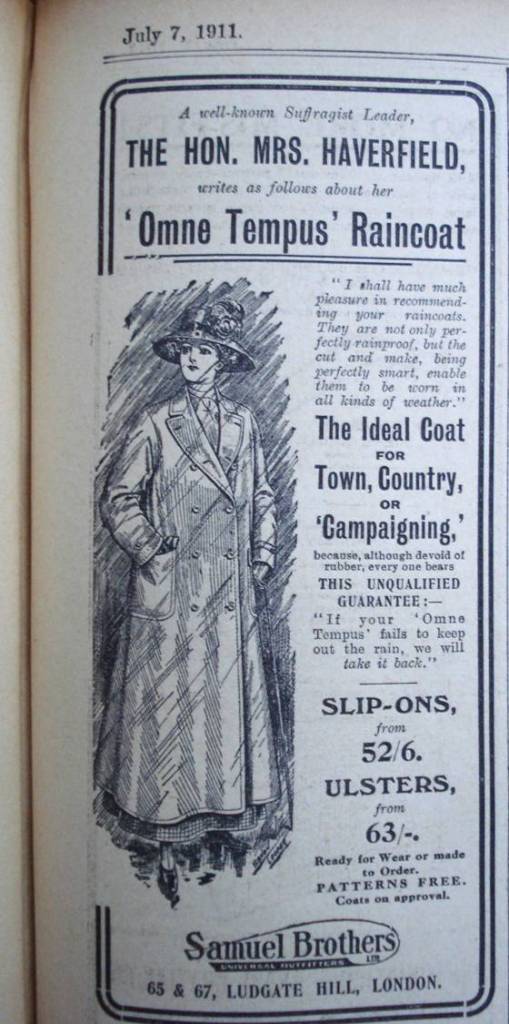

She lived with the Hon Evelina Haverfield who appeared in the pages of Votes for Women in 1912 giving her imprimatur to the Omne Tempus raincoat – an ideal coat for town, county and campaigning.

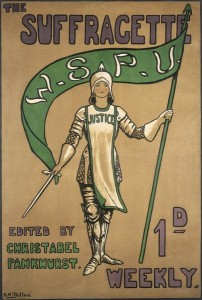

As the suffrage battle grew more ever more physical, so the imagery became more military – if of a feminised kind. This poster was used after 1912 to advertise the Suffragette,the successor paper to Votes for Women. By now, Joan of Arc was often invoked as a role model

And, paradoxically, it was the womanly skills of WSPU members that were used to make many of the banners, flags and pennants that were carried by the marchers into the suffrage battle. And to raise funds for what was actually called ‘The War Chest’, the WSPU held grand bazaars. Of these the grandest was the one held in Knightsbridge in 1909. Here, in this photograph held by the Museum of London, we see Mrs Pankhurst manning the hat stall there – she had appealed for hats, veils, scarves, hair ornaments etc’. Hats clearly had their part to play in the woman’s struggle – although hat ornamentation could arouse strong feelings. Some suffragettes, many of whom combined interests in anti-vivisection and vegetarianism with their support for votes for women, were involved in a campaign to prohibit the wearing of feathers in hats.

But hat-wearing was de rigueur – even when setting out to commit arson. To have been hatless would have been to attract attention. When Emily Wilding Davison ran in front of the King’s horse in 1913– she was wearing a hat. Newsreel, that you can watch here, shows it bowling across the grass as she fell.

After Emily Wilding Davison’s death – the WSPU gave her a magnificent funeral. You can see the women dressed – very femininely -in white – guarding the coffin, holding their lilies like swords. One rank and file member, Alice Singer, recorded in her diary the day before the funeral that she had just bought a black armband to wear as she watched the procession from the pavement. And Kate Frye (who’s diary I have edited) bought a black hat specifically for the occasion.

This was the last big pageant –soon the WSPU was being harried by the police – it had to move out of its office, many of its leaders were in prison and Christabel had fled to France to avoid arrest. The society no longer had the resources to devote to pageantry

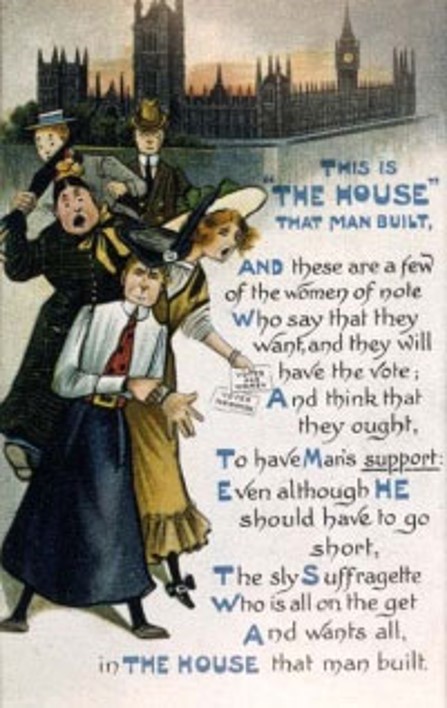

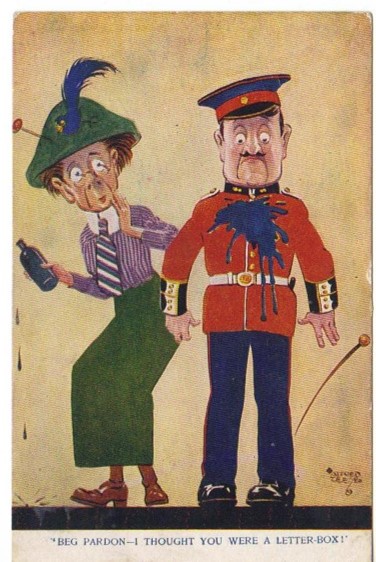

But whatever the suffragettes did to construct an image of co-ordinated determination, even if they might not always have achieved the ultimate goal of grace and nobility, the popular view of them had changed little. The Edwardian era saw the flourishing of the postcard trade and suffragettes were a boon to illustrators.

Their stereotypical attributes were glasses, big feet, tailored clothes, collar and tie, a billycock hat and an umbrella.

The image was even accepted as ‘authentic’ by the suffragettes themselves. When Lady Constance Lytton wished to ensure that she would be arrested – which, on account of her family connections, would not have happened if she had been recognised – she disguised herself as a stereotypical ‘suffragette’ – and was duly imprisoned.

Daily Life as suffragette supporter

[pic] But life as a suffragette was not all processions, marching and pageantry. It’s clear from a wide range of photographs that rank- and- file suffragettes came in all shapes and sizes and in daily life favoured a variety of ‘looks’. As I have noted, depending on the taste of the wearer, these ranged from the feminine and fancy, through the artistic, to the tailored. This range in style is reflected in the advertisements that appear in Votes for Women.

For instance, regular advertisers included Maud Barham, Artistic and original dresses, hand embroideries, djibbahs, coats and hats;

Amy Kotze, Artistic dresses and coats – for women and children – and Miss Folkard, Artistic dress and mantle maker. One woman who did favour the artistic look was prepared to make a sacrifice for the cause. On 2 November 1911 Alice Singer wrote in her diary that ‘I sold my Liberty smock to Vera Wentworth [she was another WSPU member]– proceeds 5/- to WSPU’

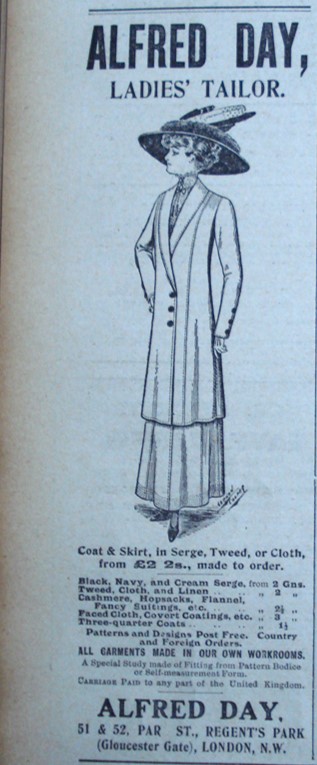

As for the tailored look, Alfred Day, ladies’ tailor, of Regent’s Park, was a regular advertiser, while the more conventional dresser was addressed by Madame Rebecca Gordon, court milliner and dressmaker.

Major stores such as Debenham and Freebody, Whiteleys and Pontings clearly thought it worth their while to advertise a variety of styles – tying in their advertising to current suffragette activities – whether electioneering or processing. Other advertisers included Regal Corset Parlor, whose slogan was – at least in Votes for Women – ‘Support the Women’.

However, whatever style was favoured, the wearing of the colours in everyday life was the sign of a committed suffragette. One writer mentions that in her experience a white costume, green straw hat and purple scarf was a very appropriate outfit for a WSPU member. In another, perhaps fictional, diary, when the suffragette heroine is persuading someone who is becoming interested in the WSPU, but does not want to fight with policemen, she tells her that ‘Derry and Toms have charming hats in the colours – they are really most becoming’ – thereby suggesting that she could participate in the fight for the vote by merely wearing the correct hat.

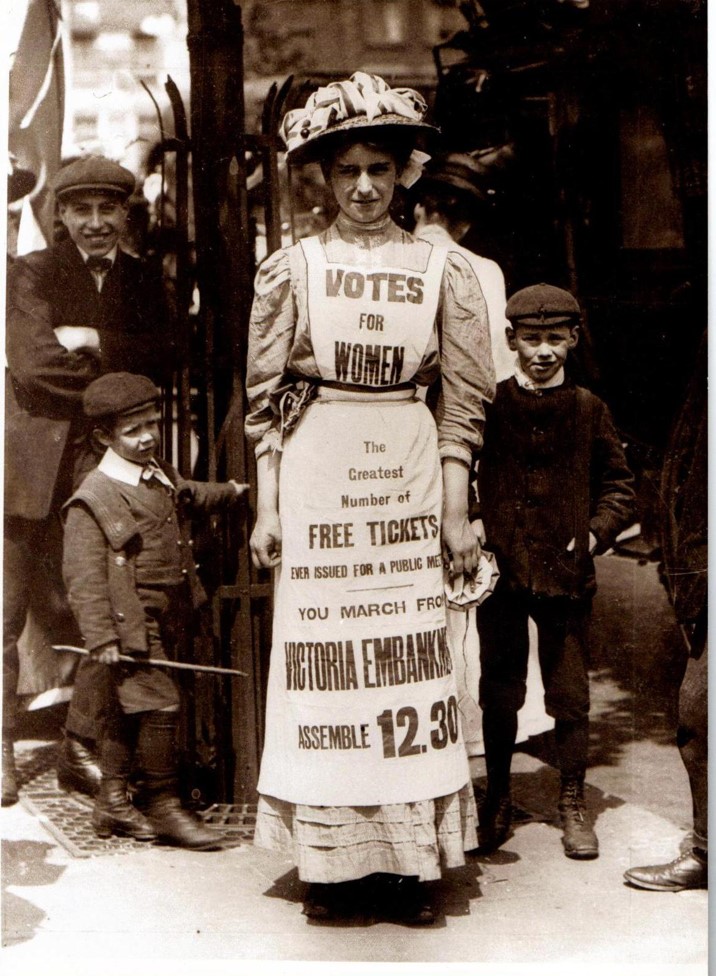

Other suffragettes were prepared to make a very much more public display of themselves. Many elderly suffragettes have recorded how, as gently-brought up girls, selling Votes for Women in the street took considerable courage. In the above photo we see that Vera Wentworth (to whom, as I mentioned, Alice Singer sold her Liberty smock) is the centre of attention as she advertises a WSPU procession.

Prison

But, increasingly, being a suffragette required more than social courage – it also involved the risk of being sent to prison. Before arrest, confrontations with the police could lead to physical manhandling and for one notorious scrum in Parliament square in November 1910 women altered their usual attire by stuffing cardboard down their fronts – armour indeed.

Many suffragettes have left memories of their time in gaol. The clothes are particularly remembered. One wrote ‘We wore a uniform – a green dress, thick serge, a little white cap on one’s head, an apron of blue and white check cotton and a round disc the colour of wash leather which had a number.’ Others remembered that in the early years underclothing was patched, stained and foul smelling – a particular horror.

But they put their prison dress to good use. Replica costumes were run up and were worn when campaigning at by elections, for parades, to show solidarity when meeting released prisoners at Holloway or, as in the photo of Mrs Pankhurst (above), at bazaars.

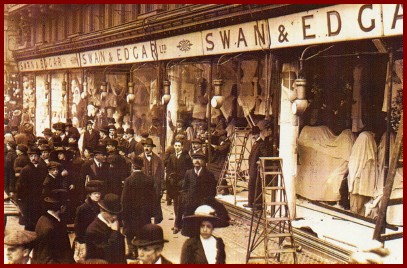

In November 1911 members of the WSPU adopted a new tactic and organised a mass breaking of windows in the West End and Knightsbridge. It was now thought that conventional methods of campaigning had achieved nothing and that violence – of a sort – was the answer. They called it the argument of the broken glass. Kate Frye, who did not actually wield a hammer, wrote in her diary on 21 November 1911, ‘I went in to Lyons and had coffee and a sandwich. Who should I happen to sit next but Miss Ada Moore [a popular actress and suffragette] and 2 ladies – ready for the fray. I wonder I wasn’t arrested as one – for I soon realized I was dressed for the part to the life. Long cloth ulster or coat, light hat and veil was the correct costume – no bag purse – umbrella or any extra.’ Muffs were a fashionable accessory at the time and were useful for concealing the hammer used to smash the windows. Three months later some members of the Chelsea WSPU adapted their dress by sewing special pockets to hang down inside their skirts in which to conceal stones to throw at windows. The attack on the very stores of which they were the main customers began shortly before closing time.

Alice Singer wrote in her diary on 24 February 1912 – ‘Wrote to offer myself as window breaking for 4th March, if Mrs Pankhurst thinks I shan’t disgrace the Cause’. And on the 27th February wrote’ Walked about the Suburb [that is Hampstead Garden Suburb] trying to find someone to make me a new frock to wear when I return from Holloway Gaol’. That certainly demonstrates a certain insouciance.

Holloway brooch – as awarded to Alice Singer for her imprisonment. She did not go on hunger strike

But it was not only imprisonment that women were prepared to face. Many also adopted the hungerstrike. Women who had undergone imprisonment and forcible feeding received recognition from the WSPU. The Holloway badge was given for imprisonment – and the medal – a metal disc inscribed with name and date suspended from a military style ribbon – for those that went on hunger-strike. These were awarded with some ceremony. For instance, on 15 June 1912, after the sentences incurred by the window breakers had been served, Alice Singer wrote in her diary, ‘rousing meeting at Albert Hall. All the 1st and 4 March prisoners released to date marched in two specially reserved places. I wore my prison-gate brooch for first time.’ These decorations were very much treasured. I’ve already mentioned that Flora Drummond is wearing her hunger-strike medal in her portrait – and many of the other leaders – Mrs Pankhurst, Lady Constance Lytton, and Mary Gawthorpe are ones that come immediately to mind – made sure that when they are photographed their Holloway badge and/or hunger-strike medal is prominently displayed.

Interestingly, for all the significance given to prison uniform, many of the women who were imprisoned and on hunger-strike in 1912 and later – were able to wear their own clothes. This was after the government had passed a rule allowing them special treatment. These photographs were taken in the exercise yard at Holloway by a hidden photographer. They were wanted by Scotland Yard to send out to museums, galleries and other likely sites of suffragette attack. The photographs are interesting as in them we can see what women of the period looked like when not dressed up for the camera. I imagine that they may not have been very useful in identifying likely attackers – as presumably when approaching a gallery or some such place the women would be rather more carefully dressed – and have regained some of their lost weight. Some WSPU members would allow nothing – not even prison – to interfere with their standards of dress. .Janie Allan, a wealthy Scot imprisoned in Holloway, was remembered as ‘always correctly dressed for Exercise in hat and lemon kid gloves’

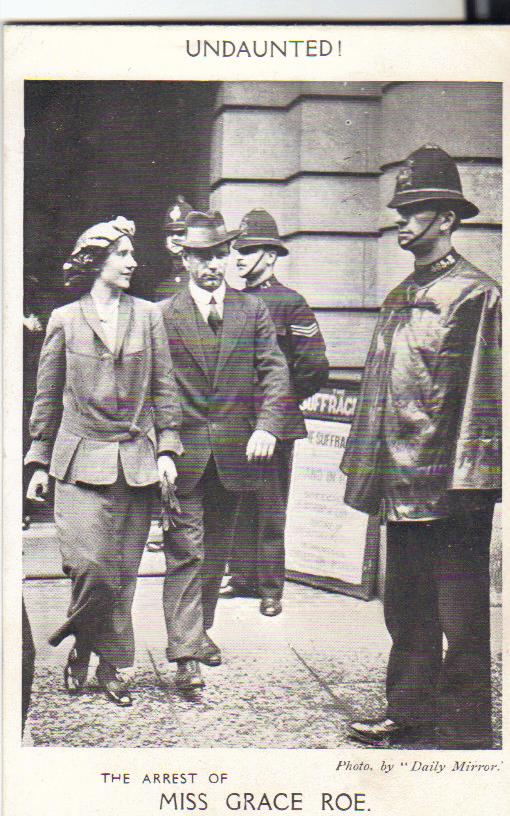

Grace Roe, Christabel’s deputy, was arrested in 1914 – wearing this rather becoming tailored suit.

Whereas Mrs Pankhurst, arrested a couple of months later while leading a violent protest outside Buckingham Palace, still retains something of her Parisian style. She took size 3½ in shoes – they look so dainty dangling there – belying all the crude postcard caricatures. In 1910 she had lost one in a scuffle with police – and it is now held by the Museum of London.

And it was to Paris that Christabel had escaped in March 1912 – just after the window-breaking campaign – to avoid arrest on a charge of criminal damage. She spent the final 2 and a half years of the campaign there – clearly very relaxed – while those who followed her militant policy were imprisoned and on hunger strike.

The WSPU campaign ended with the outbreak of war. It was the NUWSS, led by Millicent Fawcett, that in 1918 negotiated women – or at least women over 30 – to the ballot box – and to the opportunity of sitting in parliament.

So, to summarise, we have seen that the suffragettes did use dress as a weapon in their campaign. They were encouraged to dress in such a way as to define themselves as womanly – but united. To this end the WSPU attempted to impose its brand on its members – encouraging them to wear its merchandise and colours, both as they went about their daily life and when they took part in the society’s spectacular processions. The WSPU never sought to be at the avant-garde of fashion but the tailored look that became increasingly popular in the couple of years before the outbreak of war coincided with the increasingly physically-militant tactics of the suffragette campaign. Women could still be fashionable – and therefore womanly – yet present themselves in a more streamlined – less curvaceous – way than in the past. This more tailored silhouette echoed the increasingly masculine – physical force – argument that the WSPU was now professing.

I will end with an image we saw earlier – of the suffragette as a feminine warrior – a rather dainty Joan of Arc – as first depicted on the WSPU poster and here, to the right in the photograph, in the shape of a dress made by Leonora Cohen, a Leeds suffragette, to wear in 1914 to the Leeds Arts Club Ball. The paper designs, presumably cut from the poster, are pasted on the dress which is made of turquoise rayon. The dress, now preserved in Leeds City Museum, recently conserved – and rather more sophisticatedly displayed – is testament to the willingness of at least one suffragette to clothe herself in her cause.

This blog is based on a talk that I gave to the Costume Society in 2010.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement