Posts Tagged rhoda and agnes garrett

Another Blue Plaque for Enterprising Women: Rhoda and Agnes Garrett Commemorated

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on March 11, 2025

I am delighted to report that two more of my ‘Enterprising Women’ have just been recognised with an English Heritage Blue Plaque. For the work of Rhoda and Agnes Garrett is now highlighted, this new plaque joining that of their sister/cousin, Millicent Fawcett, on the outside of their home and business premises, 2 Gower Street, Bloomsbury.

The first published study of their work is detailed in a section headed ‘The Home’ in my Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle (2002). Having continued the research in the intervening years, most recent discoveries were revealed in an online talk I gave last month for the Victorian Society. If you are interested it is, I believe, possible to buy a recording.

Thus, Rhoda and Agnes Garrett are now memorialized by two blue plaques, the other being by the gate to their Rustington, Sussex, house, then known as ‘The Firs’. I had the pleasure of unveiling that one in 2018.

And while Blue Plaques are on my mind, I’ll mention that Fanny Wilkinson, entirely forgotten before I made her the subject of the section ‘The Land’ in Enterprising Women, is also now memorialised by two. One is the English Heritage version, on her one-time flat in Bloomsbury

The other is in the garden of her former family home, Middlethorpe Hall, now a delightful hotel. I had the pleasure of giving a talk about Fanny and her work to accompany that unveiling in 2022.

I may say that I initiated none of these commemorations – I just didn’t think to do so – but how delighted I am that the work of these interesting women has touched the imagination of those who launched the four proposals.

And here’s the book that started it all:

330 pages, 75 illustrations £25 +pp (can be ordered directly from me – elizabeth.crawford2017@outlook.com).

The Garretts And Their Circle: Millicent’s Writings (soon to be published) And Agnes’ Furnishings (work in progress)

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on March 8, 2022

This International Women’s Day I would like to celebrate, once again, the work of the women of the Garrett family.

In a couple of months’ time UCL Press will be publishing Millicent Garrett Fawcett: Selected Writings on which I have had the pleasure of working, alongside the lead editor, Prof Melissa Terras. In the volume, which will be open access as one of the publishing options, 35 texts and 22 images are contextualised and linked to contemporary news coverage, as well as to historical and literary references. This is the first opportunity to study in one volume Millicent Fawcett’s thinking on a range of topics concerning the advancement of women, of which the women’s suffrage campaign is only one.

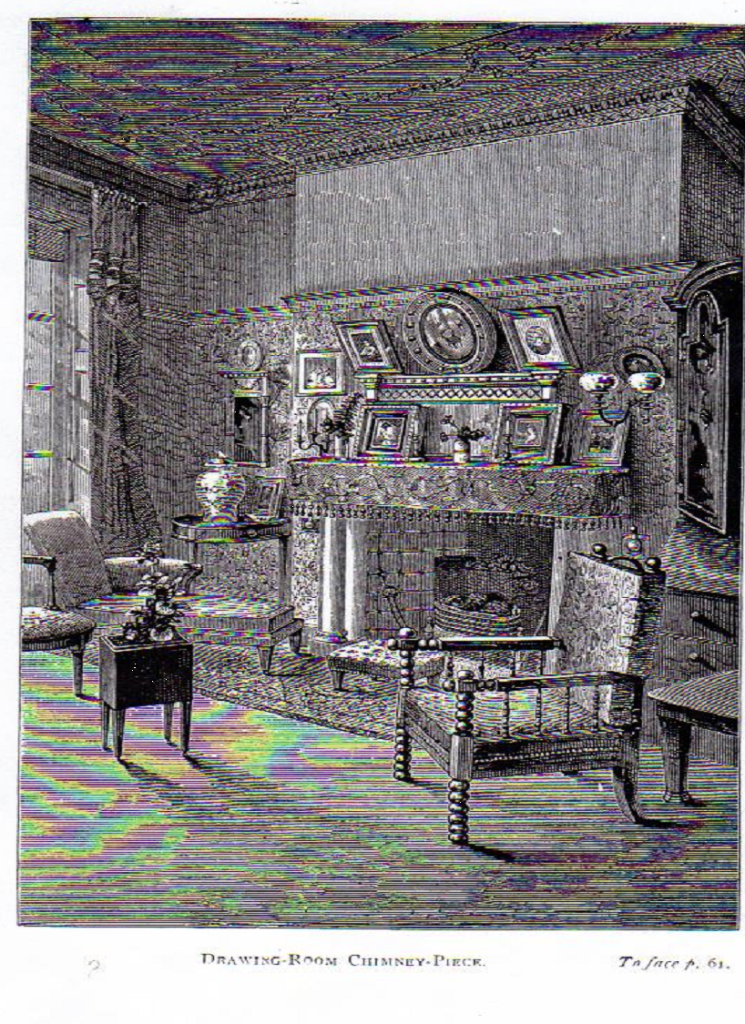

In the photograph we chose as the cover for the book you see Millicent Fawcett seated at her desk in a corner of the first-floor front drawing-room of her home at 2 Gower Street, Bloomsbury. It may be the very same desk as that of which we catch a glimpse, to the right of the fireplace in the illustration below, taken from Suggestions for House Decoration (1876) by Rhoda and Agnes Garrett. Many years ago, after visiting 2 Gower Street when researching Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle, I came to the conclusion that the illustrations in House Decoration were taken directly from real life, that is they were pictures of the rooms in 2 Gower Street, as arranged by Rhoda and Agnes. Recently I have been delighted to have my educated guess vindicated by discovering that Lady Maude Parry, a friend of the Garretts, stated in an obituary article on Rhoda, published in Every Girls’ Annual 1884, that in Suggestions for House Decoration ‘are illustrations of their house in Gower Street’.

Rhoda died in 1882, but Agnes carried on the business of ‘R & A Garrett’, house decorators, until 1905, although in 1899 the lease on the firm’s warehouse in Morwell Street came to an end, necessitating the sale of its contents and, presumably, a reduction in the work undertaken. Incidentally the Morwell Street building and its neighbours has recently, 2022, been approved for demolition, to be replaced by a 6-storey building. When I first noted it c 2000, the Garrett’s ‘warehouse’ retained its original façade (illustrated in Enterprising Women), which has subsequently been altered – now another Garrett link will be utterly obliterated. However, that furniture sale, held at Phillips, Son and Neale on 27 July 1899, has provided me with considerable scope for research – allowing me to identify a number of individuals keen to buy furniture and house accoutrements that had the Garrett seal of approval – in that they had passed through Agnes’ hands – and to muse a little on the state of the ‘house furnishing’ market at the end of the 19th century. That research will appear in a subsequent post on this website.

Copyright

All the articles on Woman and Her Sphere are my copyright. An article may not be reproduced in any medium without my permission and full acknowledgement. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement

Mrs Hartley Brown And Miss Townshend -19th-c Interior Decorators: Who Were They?

Posted by womanandhersphere in The Garretts and their Circle on February 27, 2015

In a chapter on ‘Decorative Art in England (Travels in South Kensington, 1882) Moncure Conway commended Rhoda and Agnes Garrett for their ‘admirable treatment of the new female colleges connected with English Universities’. It has always been a niggle that neither I – or anyone else – as far as I know – has ever been able to find any evidence that the Garretts did work on the interior of any women’s college.

In a chapter on ‘Decorative Art in England (Travels in South Kensington, 1882) Moncure Conway commended Rhoda and Agnes Garrett for their ‘admirable treatment of the new female colleges connected with English Universities’. It has always been a niggle that neither I – or anyone else – as far as I know – has ever been able to find any evidence that the Garretts did work on the interior of any women’s college.

As one member of the Garrett family, Elizabeth, was a close friend and supporter of Emily Davies, founder of Girton, another, Millicent, was a founder of Newnham, and Rhoda and Agnes had received their training in the office of J.M. Brydon, sharing an office with Newnham’s architect, Basil Champneys, it would not have been at all surprising if they had been involved with the interior decoration of one or other of the colleges. But neither in Garrett family letters nor in the press is there any mention of Rhoda and Agnes working on the interior of Newnham – or of Girton.

Merton Hall, Cambridge. (Photo courtesy of Cambridge 2000)

Merton Hall, Cambridge. (Photo courtesy of Cambridge 2000)In fact the only mention of work being done by women interior decorators on a Cambridge women’s college relates to furnishings for an early incarnation of Newnham – when, between October 1871 and 1874, it was housed in an ancient, rambling house, Merton Hall. The house belonged (and still belongs) to St John’s College, whose Master was very sympathetic to the Lectures for Ladies’ scheme that had been instigated in Cambridge by Millicent Fawcett, Henry Sidgwick and Jemima Anne Clough.

Merton Hall is first mentioned by Moncure Conway in ‘Decorative Art and Architecture in England’, an article published in Harpers New Monthly Magazine, November 1874. In this, after discussing the work of Rhoda and Agnes Garrett, he tells us that Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend had set up in the same business as the Garretts, in premises at 12 Bulstrode Street. He then goes on to say that ‘These ladies, who have been employed to decorate the new ladies’ College (Merton) at Cambridge, have not only devised new stuffs for chairs, sofas and wall panels, but also for ladies’ dresses.’ The fact that he uses the past tense seems to indicate that the work was already complete.

A further allusion to this partnership is made by Emily Faithfull when discussing new trade opportunities that have been opening for women. In Three Visits to America (1884) she mentions that ‘Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend, soon after entering into partnership, were appropriately employed in decorating Merton College, and devised with much success some new stuffs for the chairs and sofas for the use of Cambridge girl graduates.’

That seems quite clear: Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend had been involved with furnishing Merton Hall (later Newnham) and neither Conway or Faithfull, although discussing the Garretts’ work, made any mention of the Garrtts being similarly employed.

However, when Moncure Conway came to publish Travels in South Kensington in 1882 the Garretts were going from strength to strength and, if the silence in the press is anything to go by, Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend had gone out of business. One construction might be that, while making no mention of the latter two, Conway lauds the success of the Garretts and, carelessly assigns to them the ‘admirable treatment of female Colleges’. It may be that only one firm of female interior decorators worked on the furnishings of a female college – and that was the partnership of Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend.

But who were Mrs Hartley Brown and Miss Townshend? I have to confess to drawing a blank on Mrs Hartley Brown – but can make an educated guess at the identity of Miss Townshend.

In his Harper’s 1874 article Conway (who, as we see was prone to getting things a bit muddled) mistakenly describes Mrs Hartley Brown as ‘a sister of Chambray Brown, Esq – a very distinguished architect’. In fact what he meant was that ‘Miss Townshend was a sister of Chambray Townshend…’. The latter was indeed an architect, although not even his wife – indeed particularly not his wife – would have called him distinguished. Unfortunately for us Chambray Townshend had eight sisters. And the question is ‘which one went into business as an interior decorator?’

Well three can be discounted, being in 1874 already married. Of the remaining five, very little is known of the lives of three, although Alicia, who didn’t marry until 1880, is known to have studied art at the Slade and is I suppose a possibility. However I suspect that the two strongest candidates of the five are Isabella (1847-1882) and Anne (1842-1929).

Anne certainly seems to have the most productive work record. According to family information she trained as a nurse at London’s Foundling Hospital and was later Matron at the Hospital for Hip Disease in Childhood (Queen’s Square). When and for how long she was engaged in nursing I don’t know. By 1882 she had moved into philanthropic administration and was secretary of the Metropolitan Association for Befriending Young Servants (MABYs).

Then in 1888 she became the first secretary of the Ladies’ Residential Chambers Co (the founders of which included Agnes Garrett and Millicent Fawcett) and remained involved with the company until 1910. In 1890, when the company was planning a new set of chambers in York Street, Marylebone, it was Anne Townshend who was deputed to consult with Thackeray Turner, the architect, over the company’s specifications for the new building. However nowhere in the minutes of the Ladies’ Residential Co is there any suggestion that she was ever involved with the interior design of either of the buildings.

Isabella Townshend is the more artistic candidate – and she does have a very clear Cambridge connection- being one of the Girton Pioneers. In 1869 she was one of the first five to join Emily Davies at her new college at Hitchin (it was not yet ‘Girton’). She left without taking a Tripos at Easter 1872. Could she then have gone into the interior decorating business?

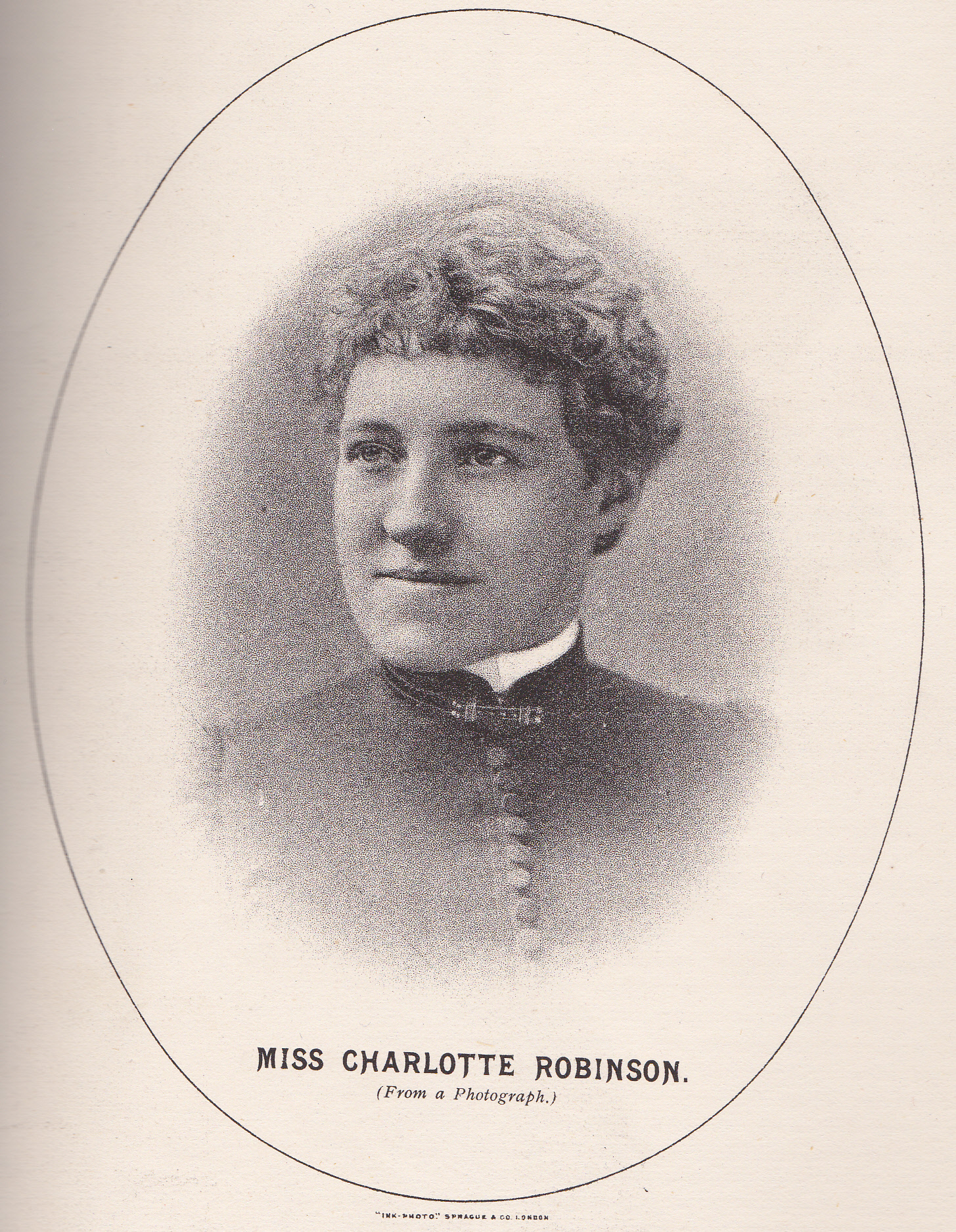

In Girton College, Barbara Stephen comments that ‘Miss Townshend was not striking in either appearance or manner‘, while reporting Barbara Bodichon’s opinion that [Isabella’s] ‘interests were wide and her mind original’ Barbara Stephen was too young ever to have met Isabella; perhaps she made her rather harsh judgement on the basis of this photograph she included in her book

However, Isabella certainly made a very strong impression on her fellow Pioneers – particularly on Emily Gibson. When Isabella left Hitchin in the 1872 without taking a Tripos (perhaps it was this high-handed approach to all that Miss Davies had to offer that attracted Barbara Stephen’s disapproval) Emily followed suit and the following year married Isabella’s brother, Chambray Townshend.

However, Isabella certainly made a very strong impression on her fellow Pioneers – particularly on Emily Gibson. When Isabella left Hitchin in the 1872 without taking a Tripos (perhaps it was this high-handed approach to all that Miss Davies had to offer that attracted Barbara Stephen’s disapproval) Emily followed suit and the following year married Isabella’s brother, Chambray Townshend.

In Some Memories for Her Friends., Emily wrote of Isabella: ‘She was more mature than many of us, and in quite a different stage of development, but the sort of position she held among us, the sort of influence she exercised over me was chiefly due to her having been swept over by a very early wave of that current of aestheticism which was then just beginning to gather force. The sort of doctrine she taught, or rather that she gave living expression to, was, that the most valuable means of culture was to be found in the enjoyment of the beautiful in nature and art, that a beautiful combination of colours, a delicate bit of decorative work seen and cared for in a reverent and appreciative spirit, could do more for us in the way of training and development than much steady grinding away at mathematics and classics.’

‘She had considerable ability, indeed, many of us gave her credit for a touch of genius, yet she never accomplished much definite work of any kind.’..Isabel took the utmost pains to live from hand to mouth. She would work hard now and again when she felt the subject in hand to be worth working at, but she scorned to tie herself down to do things against inclination for the sake of obtaining some definite mundane good.’

Isabella Townshend, self-portrait, (c) Girton College, University of Cambridge. Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Isabella Townshend, self-portrait, (c) Girton College, University of Cambridge. Supplied by The Public Catalogue FoundationIsabella Townshend was undoubtedly ‘artistic’. Isn’t this a wonderful self-portrait – bequeathed to Girton by Emily Townshend? It wouldn’t at all surprise me if Isabella had not ‘devised new stuff’ for her dress and designed it herself. But did she have the stamina to set up in business? Emily Gibson mentions that in the period between leaving Cambridge and her marriage to Chambray Townshend, he and Isabella were particularly friendly with Walter and Lucy Crane – so she was certainly moving in art design circles.

There is no doubt that interior decorating ran in the family veins. In his Harper’s article Moncure Conway wrote ‘I have become convinced by a visit to a beautiful house which Chambrey Townshend arranged at Wimbledon, that there can be nothing so suitable for somewhat dark corridors and staircases as a faint rose tint. In Mr Townshend’s house, however cold and cheerless the day may be, there is always a glow of morning light. This gentleman has shown that a sage-gray paper with simple small squares (such as Messrs Marshall & Morris make) furnishes a good dado to support the light tints upon walls not papered.’

The house may well have been the Townshend family home at 12 Ridgway Place, Wimbledon, where the unmarried sisters lived with their mother.

Unfortunately Chambray Townshend took the same laissez-faire approach to work as did Isabella. Of him Emily, his wife, later wrote ‘Chambrey Townshend had little push and no business ability to back up his remarkable artistic abilities.’ After his death she regretted she hadn’t devised some opening for his remarkable talent for house decoration ‘when architectural work was not forthcoming’.

If the interior decoration business was run by Mrs Hartley Brown and Isabella Townshend, it may be that Isabella soon lost interest. In the early 1880s she went to Italy to study painting and died in 1882. The Girton Register has it that she died in Italy, ‘of typhoid fever contracted at Capri’. It may well be that she became ill in Italy, but the Probate Register shows that she died on 20 July 1882 at Ealing and was buried at Perivale on 25 July 1882.

So, although Anne Townsend had the stamina and application to run a business, I’m inclined to think that it was Isabella Townshend who, for a brief period, was in partnership as an interior decorator with Mrs Hartley Brown and who provided the furnishings for Merton Hall, the early incarnation of Newnham.

For more about the interior decoration business run by Rhoda and Agnes Garrett see here.

**