Mary Richardson, c 1913. This image of her was included in the sheet of ‘surveillance photographs’ of known suffragettes sent to museums and art galleries

Mary Richardson, c 1913. This image of her was included in the sheet of ‘surveillance photographs’ of known suffragettes sent to museums and art galleriesI was asked the other day to speak briefly on Woman’s Hour about Mary Richardson, the suffragette who took a hatchet to the Velasquez painting, The Toilet of Venus -known as The Rokeby Venus , while it was on display in the National Gallery in March 1914.  You can listen to the resulting piece – which includes a clip from a 1957 Woman’s Hour interview with Mary Richardson – here.

You can listen to the resulting piece – which includes a clip from a 1957 Woman’s Hour interview with Mary Richardson – here.

Looking again at Mary Richardson’s story – as she tells it in her suffragette autobiography, Laugh a Defiance – I was interested in a brief mention she made of the house from which she set out for the National Gallery on that fateful day – Tuesday 10 March 1914. It was a house in which she had been given shelter when she was let out of Holloway the previous October under the terms of the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, after going on hunger strike. She continued to live there clandestinely – as a ‘mouse’ – evading the police.

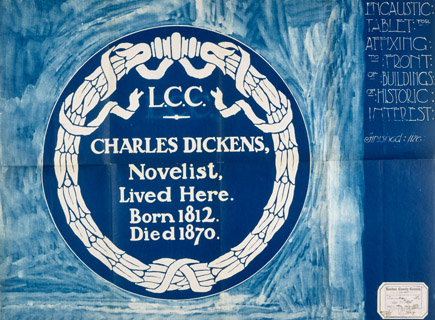

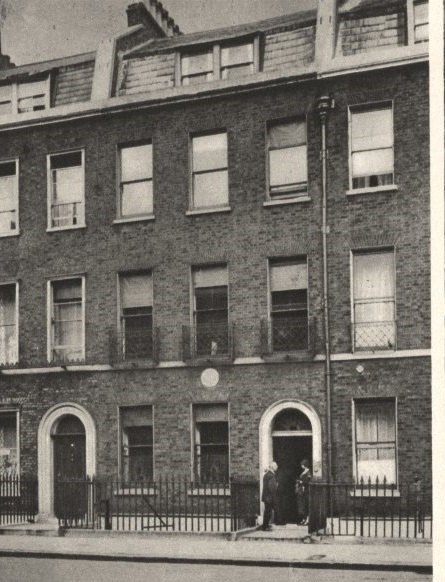

As she tells it, this house in Doughty Street in Bloomsbury had once been the home of Charles Dickens but was now under the charge of a ‘Mrs Lyon’. Investigation reveals that in 1914 the house that was Dickens’ home from 1837-9 and is now the Charles Dickens Museum was, together with number 49, a boarding house run by a Miss Jane Lyons.  Mary Richardson wrote that she knew immediately that it was to Dickens’ house that she had been brought. Indeed she would have, for as she left the motor car that had carried her from Holloway she would have seen this plaque, which had been placed on the front of 48 Doughty Street by the LCC in 1903. Once settled into the boarding house doubtless she would have heard from Miss Lyons more about the famous connection that gave cachet to the establishment.

Mary Richardson wrote that she knew immediately that it was to Dickens’ house that she had been brought. Indeed she would have, for as she left the motor car that had carried her from Holloway she would have seen this plaque, which had been placed on the front of 48 Doughty Street by the LCC in 1903. Once settled into the boarding house doubtless she would have heard from Miss Lyons more about the famous connection that gave cachet to the establishment.

Number 48 Doughty Street was acquired by the Dickens Fellowship in 1923 and opened as the Museum in 1925. Interestingly the Museum has quite recently acquired number 49 – so that the two houses are now interlinked as they presumably were when Mary Richardson was given shelter in Miss Lyons’ boarding house.  When Mary Richardson made her acquaintance in 1914 Miss Lyons would have been 78 years old. She may well have been given the honorary title of ‘Mrs’ and it isn’t particularly surprising that Mary Richardson had, 40 years or so later, slightly misremembered her surname. The only information that Mary Richardson offers about ‘Mrs Lyon’ was that she had once been housekeeper to Benjamin Disraeli. Could that have been true?

When Mary Richardson made her acquaintance in 1914 Miss Lyons would have been 78 years old. She may well have been given the honorary title of ‘Mrs’ and it isn’t particularly surprising that Mary Richardson had, 40 years or so later, slightly misremembered her surname. The only information that Mary Richardson offers about ‘Mrs Lyon’ was that she had once been housekeeper to Benjamin Disraeli. Could that have been true?

Jane Lyons had been born in Plymouth in 1836, one of the eldest in a large family – of possibly 12 children. Her father, Moses Lyons (who also gave his name on various censuses as ‘Lewis Lyons’ and ‘Morris Lyons’) was a licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries – that is, he was qualified as a doctor and practised as both a doctor and as a dentist. He had been born in Coventry c 1811; his mother had been born in Russia. The family were probably Jewish in origin – although there is no evidence that they practised that religion. One sister, certainly, was married in a Congregational church. In 1871 the Lyons family was living in the Islington area of Birmingham and Jane Lyons worked with her mother and five of her sisters in the family’s stationers shop.

By 1881 Jane Lyons had come to London and on the night of the census, 3 April 1881, was living in a boarding house at 72 Gower Street in Bloomsbury, described as an ‘annuitant’. So it doesn’t appear that she was Disraeli’s housekeeper at the time of his death – which occurred 16 days after the census was taken. But I suppose it is not impossible that she was so employed at some time during the previous decade.

By 1891 Jane Lyons was housekeeper at ‘Brunswick House’, 56 Hunter Street, Bloomsbury. Here lived 45 boarders – all women – most of whom were working – as teachers, typists, clerks, and artists.

48 Doughty Street – post 1903

48 Doughty Street – post 1903Ten years later, in 1901, Jane Lyons was the proprietor of a ‘Private Hotel and Boarding House’ at 48 & 49 Doughty Street. Here, on the day of the census, she had 24 boarders – all women – again clerks, teachers and typists (and a stockbroking nephew). By 1911 Miss Lyons’ clientele had slightly changed – now numbering a good half-dozen men among her boarders.

Miss Lyons, as a single woman running her own business, was very much the type of woman we might expect to support the ‘votes for women campaign’ – perhaps as a member of the Tax Resistance League. But from Mary Richardson’s evidence she went that bit further and gave active support to those who were evading the police. According to Mary, while she was living at number 48 Annie Kenney, who was also on the run, stayed for a time in Miss Lyons’ boarding house. I wish I knew more about Miss Lyons.

In Laugh a Defiance Mary Richardson relates that she had planned her attack on the RokebyVenus in advance – presumably while living under Miss Lyons’ roof. Indeed she states that she had sought approval from Christabel Pankurst for her plan. But never once in Laugh a Defiance can I find any mention of the fact that since March 1912 Christabel had been living in Paris. Mary Richardson refers to her as though she were living close by, convenient for consultation. I find it difficult to believe that in those febrile months in 1914 Mary Richardson was in such close contact with Christabel. Did she, 40 years later, feel it necessary to justify her actions by implying that she was always ‘acting on orders’?

The sequence of events ran like this. Mrs Pankhurst was arrested in Glasgow during the evening of Monday 9 March – after something of a battle with the police at a meeting in the St Andrew’s Hall. Around her was a bodyguard of women – one of whom was Mrs Lillian Dove-Willcox, with whom Mary Richardson was closely associated.

Lillian Dove-Willcox (photo courtesy Bath In Time website)

Lillian Dove-Willcox (photo courtesy Bath In Time website)After one of her hunger strikes Mary had recuperated at Lillian’s cottage in the Wye Valley and their friendship seems to have lasted all Mary’s life. Symbol Songs, a collection of poems she published in 1916 contains ”The Translation of the Love I Bear Lillian Dove’ – and it was Lillian (by now, after remarriage, Mrs Lillian Buckley) who wrote Mary’s obituary for the Suffragette Fellowship newsletter. It wouldn’t surprise me that if the ‘Rokeby Venus’ plan had been shared with anyone, it had been shared with Lilian Dove-Willcox, who travelled back from Glasgow on the train in which Mrs Pankhurst was being escorted by the police.

However the train stopped at a station short of Euston and Mrs Pankhurst was taken off it and driven straight to Holloway in order to avoid the suffragette crowds that were awaiting her at the terminus. The news of her arrest was in the Tuesday morning papers. I don’t really want to add any (quite gratuitous) speculation to Mary Richardson’s already rather unreliable memoir, but I’m going to anyway.

Could Mary Richardson have seen Lilian Dove-Willcox early that Tuesday morning and heard first-hand of the dramatic events in the St Andrew’s Hall? And dramatic they were. It was a violent scene – with clubs wielded by the women and a gun – loaded with blanks – fired by Janie Allan, a wealthy Scottish supporter. A report from the front line, made by a close friend, or even the knowledge that such a friend had been involved in such a battle could have been the real catalyst for choosing this day of all days for putting her plan into action. Doughty Street is only a short distance from Euston. Although Mary Richardson says in a radio interview that she was in the National Gallery as early as 10 am, The Times report, Wednesday 11 March, mentions that she was there at 11 .

Mary Richardson is not explicit as to whether she had already purchased her weapon of choice – a butcher’s chopper – although she does state that she bought it in the Theobald’s Road – a main road close to Doughty Street .However, because, as she repeatedly explains, she fixed the chopper into her sleeve with a chain of safety pins (though I can’t quite work out how the first in the chain was attached to the chopper??) it seems unlikely that she would have undertaken this rather cumbersome exercise on her way to the National Gallery, suggesting that she had the chopper already primed, as it were, in her room in the boarding house.

In another BBC radio interview, broadcast on 23 April 1961 – click here to listen to it – Mary Richardson revealed that she had chosen the Rokeby Venus because she hated women being used as nudes in paintings – she had seen the picture gloated over by men, and she ‘thought it sensuous’. In the 1957 Woman’s Hour interview she mentioned that she felt the painting was held in high regard because it was so financially valuable (it had cost £45,000 when purchased in 1906), whereas Mrs Pankhurst’s life counted for nothing. Presumably she was unaware that it was a fellow suffragist, Christiana Herringham, who had been the driving force in the setting up of the National Art Collections Fund – the organization that bought the painting for the nation.

In the later interviews Mary Richardson doesn’t mention that Mrs Pankhurst had only just been rearrested – but tells the story as though Mrs Pankhurst had been held for a long time, on hunger strike, in a damp underground cell in Holloway – and that her life was in danger. But, as we see, Mrs Pankhurst could have barely reached Holloway by the time Mary set out from number 48. I have mentioned that Mary Richardson’s Laugh a Defiance is an unreliable memoir. At the most basic level the account she gives of her involvement in the suffragette campaign is not chronologically accurate – rather she presents a series of incidents, in each of which she takes a starring role. I have little doubt that the purpose of Laugh a Defiance was to raise funds. It doesn’t appear that Mary Richardson was ever in full-time employment and, although she had presumably inherited some money from her family, at the end of her life the income must have dwindled. At the time of her death in 1961 she was living in a single room – in Hastings. Obviously in order for such a book to sell it did have to be packed with dramatic incident.

I have mentioned that Mary Richardson’s Laugh a Defiance is an unreliable memoir. At the most basic level the account she gives of her involvement in the suffragette campaign is not chronologically accurate – rather she presents a series of incidents, in each of which she takes a starring role. I have little doubt that the purpose of Laugh a Defiance was to raise funds. It doesn’t appear that Mary Richardson was ever in full-time employment and, although she had presumably inherited some money from her family, at the end of her life the income must have dwindled. At the time of her death in 1961 she was living in a single room – in Hastings. Obviously in order for such a book to sell it did have to be packed with dramatic incident.

I can find no reviews of the book in contemporary newspapers or magazines – or, to be accurate, in ones that are now digitized. The only quote used in its publicity by the publisher, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, was a remark by C.V. [Veronica] Wedgwood who on the radio programme, The Critics, described it as ‘A document – ingenious and absolutely genuine’. Well, yes, ‘ingenious’ is perhaps the word to describe Laugh a Defiance for although Wedgwood was an historian she clearly had not interrogated the accuracy of the ‘document’.

Leaving aside quibbles about who did what, when or where, the book contains laughable examples of ‘cod history’ – such as when Mary in Holloway describes her view onto what she describes as the site, in Elizabethan times, of the banqueting hall of the Earls of Warwick. Doubting very much that those Earls had ever had a London home in Parkhurst Road, Holloway, I did a little research to try to discover what had been in Mary Richardson’s mind. The answer: that when the prison was built in the mid-19th century the architect copied the design of the gatehouse from Warwick Castle. Such is the way that the most innocuous facts become corrupted and I’m certain that Mary Richardson’s suffragette autobiography contains many more such elisions and half-truths. Rubbed up and polished, they presented a dashing and easily digested history designed to appeal to the general reader.

I have always wondered what her fellow suffragettes made of Mary Richardson’s Laugh a Defiance – and of her two broadcasts. The Suffragette Fellowship, the organization to which many former members of the WSPU and the Women’s Freedom League belonged, was by no means devoid of factional infighting. Certainly she appears to have felt quite at ease when, a couple of years after the book was published (but before the radio programmes were broadcast), she attended a Suffragette Fellowship reunion at Caxton Hall (you can watch her here on a Pathe newsreel as she shows her very distinctive hunger-strike medal to a policeman. I wonder if any comments were made about the accuracy of her recollections?

For instance, as far as I can discover, no member of the WSPU ever mentioned that Mary Richardson was, as she claimed, at the Derby watching Emily Wilding Davison as she stepped into the path of the King’s horse. Why was such a valuable first-hand account not written up in The Suffragette or Votes for Women? Why was she not called as a witness at the inquest? In her telling the expedition to Epsom was not clandestine – rather she was following an order from Headquarters to go there to sell The Suffragette. She doesn’t go so far as to say that she accompanied Emily Davison but somehow out of the seething Derby crowd – the hundreds of thousands that swarmed over Epsom Downs – she was able to spot Emily and position herself at the opposite side of the track at Tattenham Corner. Exciting reading – but is it history?

However, Mary Richardson’s account in Laugh a Defiance of her attack on the Rokeby Venus accords very accurately with the contemporary newspaper reports. There was, of course, no need to dress up that drama – for she was (with Venus) undoubtedly the star of that particular episode.

As this is a blog post – not an academic article – I will allow myself another flight of fancy. I live not far from Doughty Street and am a regular passenger on the No 38 bus that runs along Theobalds Road. By 1914 this bus route had been in operation for a couple of years and, unless Mary Richardson walked to the National Gallery, may well have carried her as far as Cambridge Circus, bringing her within striking distance, as it were, of the Gallery. It is these gossamer connections – the layers of history through which we pass – that continue to amuse me. If I were sufficiently fanciful I could link Mary Richardson and the Rokeby Venus to both the number 38 bus, on which, incidentally, I travelled part of the way to my date with her in the Woman’s Hour studio, and to Charles Dickens, the shade of whose footstep she touched as she made her determined way over the threshold of 48 Doughty Street that March morning.

P.S. Coincidentally another nude, George Clausen’s Primavera, attacked by Maude Kate Smith in the RA Summer Exhibition in 1914, was sold by Christies on 17 June 2014, the day after my Woman’s Hour piece – for £92,500. You can listen to Miss Smith describing how she attacked the painting in a recording held by the Women’s Library@LSE.

PPS Readers who have been kind enough to visit from the Persephone Books website and are of a ‘Persephone mind’ (although equipped with non-Persephone technology – ie an e-book reader) will, I hope, find a GOOD READ in the life of Kate Parry Frye – who was very much a ‘Persephone’ woman. Read all about her here.

#1 by Sally Alexander on June 23, 2014 - 9:06 am

The slashes across the back of the Rokeby Venus look shockingly visceral – horrifying. The tailored suits, neat hats with veils tucked up, lisle stockings and sensible shoes at the suffragette reunion in 1955 (Pathe news) recall so many maiden aunts, school teachers of the forties and fifties. Fascinating.

#2 by JulesInTO on July 27, 2014 - 1:21 pm

I heard you and the audio of Mary Richardson on the Women’s Hour podcast and I was really intrigued. I wanted to read her book but I couldn’t find it in the Toronto library system or online. Even Google books’ digitized version of “Laugh a Defiance” is not available. I don’t understand why. Then I thought I would search for you and voila – this blog post is very informative and answers some questions. Thank you, Elizabeth!

#3 by womanandhersphere on July 28, 2014 - 9:04 am

Delighted you found the blog post informative. Yes, ‘Laugh a Defiance’ is quite scarce now – although years ago it was not at all uncommon in secondhand bookshops in England. Mind you, her history is, as I’ve pointed out, pretty unreliable and if not read with an eye to this her account only muddies the waters of history. I’ve tried to separate her truth from fiction- although the reasons why she felt it necessary to ‘beef up’ her history are interesting in themselves. Elizabeth

#4 by Helena Wojtczak on June 24, 2022 - 8:51 am

“But, as we see, Mrs Pankhurst could have barely reached Holloway by the time Mary set out from number 48.”

Mrs Pankhurst boarded the train at Coatbridge, Scotland, at 10.30am, so when Mary was arrested at 11.10am. Mrs P was steaming through the Scottish countryside. She did not reach Holloway till the evening.

In 1926 Mary told readers of “The Vote” that, when she arrived in London, she “lodged in Charles Dickens’ old house in Doughty Street, and there met the Kennys, fresh from Manchester.”

Annie and Jessie Kenney moved from Manchester to London in 1906; Mary did not live in Doughty Street until 1914.

#5 by womanandhersphere on August 11, 2014 - 9:29 am

Many thanks for the link. You might also like my 17 July post on the NPG exhibition – see https://womanandhersphere.com/2014/07/17/suffrage-stories-100-years-ago-today-17-july-1914-the-national-portrait-gallery-and-thomas-carlyle/